Abstract

Aim:

Precarious employment is known to be detrimental to health, and some population subgroups (young individuals, migrant workers, and females) are at higher risk of precarious employment. However, it is not known if the risk to poor health outcomes is consistent across population subgroups. This scoping review explores differential impacts of precarious employment on health.

Methods:

Relevant studies published between 2009 and February 2019 were identified across PubMed, OVID Medline, PsycINFO, and Scopus. Articles were included if (1) they presented original data, (2) examined precarious employment within one of the subpopulations of interest, and (3) examined health outcomes.

Results:

Searches yielded 279 unique results, of which 14 met the eligibility criteria. Of the included studies, 12 studies examined differences between gender, 3 examined the health impacts on young individuals, and 3 examined the health of migrant workers. Mental health was explored in nine studies, general health in four studies, and mortality in two studies.

Conclusion:

Mental health was generally poorer in both male and female employees as a result of precarious employment, and males were also at higher risk of mortality. There was limited evidence that met our inclusion criteria, examining the health impacts on young individuals or migrant workers.

Keywords: employment, wider determinants, precarious, inequalities, review

Introduction

The association between better health outcomes and good quality, stable employment is well established,1,2 and good employment is one of the essential conditions for health equity.3 In recent decades, employment trends have seen a marked increase in flexible, non-standard arrangements, contributing to reduced job security, reduced income security, and increased temporary contracts.4–6 Since 1995, more than half of the new jobs created in the European Union have been part-time, non-contracted, or insecure positions.3,5 There are a number of factors that have contributed towards changes in the trends in employment, including technological advancements and globalisation contributing to the worldwide mobility of workers and capital,4,7,8 a declining influence of unions,6 diminishing social protection including labour market reform,6,9 and economic downturn caused by recession and austerity.5,9 Furthermore, recent global recessions and associated high unemployment rates have disempowered workers4,10 and seen the increase of precarious employment arrangements. The Covid-19 pandemic will have undoubtedly worsened many of these trends.

There is no single definition of precarious employment, but it is recognised as a multidimensional construct encompassing dimensions of employment insecurity, incorporating both length of contract and perceptions of job insecurity; individualised bargaining; relations between workers and employers; low wages and economic deprivation; limited workplace rights and social protection; and powerlessness to exercise legally granted workplace rights.5,11 Some population subgroups, namely younger people, migrant workers, and women, are more likely to be in precarious employment.8,12–14 Young adults are particularly vulnerable in the labour market, as they lack work experience, qualifications, and available employment opportunities.15 Precarious employment conditions expose younger individuals to health inequalities from constant transition in labour market activity; in particular, impact on mental health and increased health risk behaviours, likely contributed to by the lack of economic and social benefits.15 Migrant workers are also at increased risk of precarious employment arrangements; they are subject to discrimination and exploitation, further adversely impacting on mental wellbeing.7,16 Women are more often employed in precarious, low-paying occupations, including those within the care sector, than their male counterparts.5,17

Despite relying heavily on one-dimensional constructs such as temporary contracts or the perception of job insecurity,5 the majority of the literature suggests that compared to permanent employment contracts, precarious employment arrangements can have a negative impact on the general, physical, and mental health of individuals.1,3,18,19 The effect can also extend beyond the individual, to indirectly impact on the household and family unit, through stress and material deprivation.20,21 The quality of the local labour market can also affect the wider community through reduced spending power and decline in community participation.5,22 Considering the wider-reaching social and wellbeing implications of precarious employment, it has been suggested that precarious employment is now an emerging social determinant of health.6

It is relatively unknown whether the association(s) between precarious employment and poor health is the same across groups at risk of precarious employment, that is, is the health impact of precarious employment worse for some than others. Over a decade ago, it was reported that the health of women, although disproportionately affected by precarious employment, is often neglected in research studies.17 This is a scoping review to explore the current evidence base and whether the differences in health outcomes are fully explored across population subgroups at the greatest risk of exposure to precarious employment (young individuals, migrant workers, and women).

Methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

The methodology adopted in this study followed the framework for scoping reviews outlined by Arksey and O’Malley.23 For this review, articles were included if (1) they presented original data; (2) examined precarious employment within one of the subpopulations of interest (younger people, migrant workers, women); and (3) examined differences in health outcomes. The following limits were also applied as eligibility criteria: full texts written in English and published (including online ahead of print) from 2009 to February 2019. Literature searches were performed in March 2019 and four electronic databases (PubMed, OVID Medline, PsycINFO, and Scopus) were used as sources. In addition to these sources, manual searches were undertaken on the reference lists of previous reviews on the topic area. The search keywords, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terminology, and search strings were agreed between the authors and verified by the Public Health Wales Observatory Evidence Service. In brief, the search strategy used for this review was as follows (‘employment’ OR ‘work’) AND (precarious OR casual OR temporary OR zero hours) AND ( ‘health’) AND (‘socioeconomic factors’ OR inequalit*).

Study selection and summary of results

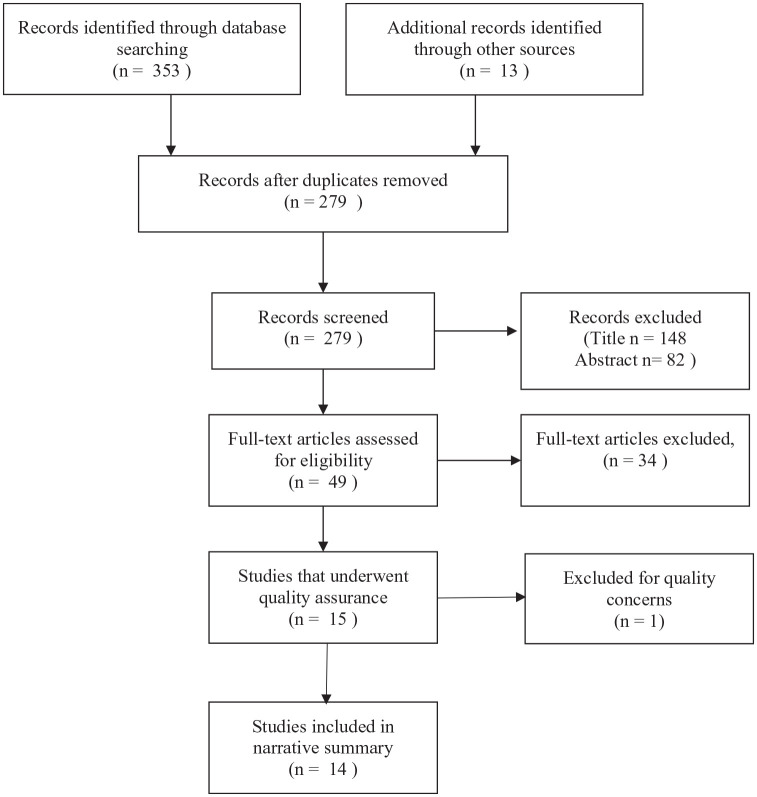

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the study selection process. The initial database searches yielded 353 titles, and an additional 13 articles were retrieved through manual searches. Following the removal of duplicate articles, 279 unique results remained. At least two of the authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the unique articles and excluded any that did not meet the eligibility criteria. The opinion of a third author was sought to resolve disagreements on the inclusion of articles. After title and abstract screening, full-text reviews were undertaken on 49 articles, again by two reviewers, of which 34 were excluded, leaving 15 studies remaining for quality appraisal. The quality of the studies was assessed by two reviewers using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal checklists for cross-sectional and cohort studies as appropriate.24 One study was subsequently excluded because of quality concerns, leaving 14 studies for inclusion in this review. The key observations from the eligible studies are presented as a narrative summary and focus on the three subpopulations disproportionately at risk of exposure to precarious employment.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of study selection

Results

Study characteristics

The majority of the studies (11 out of 14) were undertaken in Western Europe; two of the studies were undertaken in South Asia (Japan and South Korea) and the remaining study was undertaken in the Australian population. All the studies were observational, four were cross-sectional25–28 and the remaining ten were cohort studies (Table 1). The data sources for the studies ranged from country-specific postal or repeated surveys, study-specific questionnaires, or data from existing large-scale, regional surveys (Table 1). In regard to the quality of the studies, there were no issues with any of the cross-sectional studies; however, there were some minor queries about the follow-up procedures in some of the cohort studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Overview of included studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, country | Study design | Participants (% males) | Data source | Aim/research question | Exposure | Qualitya |

| Canivet et al.,32 Sweden | Cohort | 1135 (40.6% males) | Scania Public Health Cohort | Investigate the associations between precarious employment situations and mental health later in life among young adults aged 18–34 years. | Precarious employment situation. Defined as: (1) contingent work with a perceived risk of future unemployment, (2) previous unemployment, (3) those with moderate to high self-rated risk of future unemployment, and (4) presently unemployed. | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Fiori et al.,26 Italy | Cross-sectional | 20,432 (no details provided on gender split) | Health Conditions and Access to Health Services Survey | Is there a significant relationship between greater employment insecurity and worse mental health among the youth labour force in Italy? | Employment insecurity (fixed-term contract; atypical contract). | No concerns |

| Julià et al.,28 Spain | Cross-sectional | 4430 (56.2% males) | Second Psychosocial Work Environmental Survey | To test the existence of a general precarisation of the Spanish labour market and its association with mental health for different types of contract. | Temporary contract and employment calculated as high precariousness (EPRES ⩾ 2). | No concerns |

| Kachi et al.,35 Japan | Cohort | 15,222 (55.7% males) | Longitudinal Survey of Middle-aged and Elderly Persons | Examine whether precarious employment increases the risk of serious psychological distress. | Precarious employment (part-time employee, temporary agency worker, fixed-term contract). | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Khlat et al.,38 France | Cohort | 2500 (56.1% males) | Lorhandicap Survey | Is the mortality of temporary workers higher than that of workers with permanent employment? | Temporary employment. | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Kim et al.,36 South Korea | Cohort | 2891 (64.8% males) | Korean Welfare Panel Study | Examined how change in employment status is related to new-onset depressive symptoms and whether this association differs by gender. | Precarious workers. Those that did not meet all four of the following criteria: (1) directly hired by their employers; (2) full-time workers; (3) no fixed term in their employment contract; (4) a high probability of maintaining their current job. | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Minelli et al.,29 Italy | Cohort | 37,782 observations (49.2% males) | Survey on Household Income and Wealth | Offer evidence on the relationship between self-reported health and employment status. | Temporary workers. Comprises job contracts such as apprenticeships, on-project jobs, and seasonal jobs. | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Niedhammer et al.,37 France | Cohort | 4118 (53.2% males) | Lorhandicap Survey | Analyse the association between SES as measured using occupation and two measures of all-cause mortality, premature and total mortality. | Temporary contract | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Pirani and Salvini,31 Italy | Cohort | 1831 (64.5% males) | Italian EU-SILC panel 2007–2010 | Are (Italian) workers on temporary contracts more likely to suffer from poor health than those with permanent jobs? | Temporary employment (fixed-term contract) | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Richardson et al.,34 Australia | Cohort | 38,369 observations (49.5% males) | Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey | Investigate the impacts on mental health of employment on these. Terms (casual, fixed-term) and of unemployment. | Casual employment or fixed-term contract | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Robert et al.,33 Spain | Cohort | 214 (53.7% males) | ITSAL I and II (Immigration, Labour and Health) Project | Evaluates the influence of changes in employment conditions on the incidence of poor mental health of immigrant workers (in Spain), after a period of 3 years. | Temporary contract | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Samuelsson et al.,30 Sweden | Cohort | 877 (52.2% males) | Questionnaire data was used from a 27-year follow-up study of school-leavers carried out in Luleå in the north of Sweden | To investigate whether type of employment was related to work characteristics and health status at age 42. | Temporary employment. Measure by six questions on: project/object, substitute, probationary, on demand, seasonal, and other fixed-term contracts. | Minor concern on follow-up methods |

| Sidorchuk et al.,27 Sweden | Cross-sectional | 51,118 (52.3% males) | Stockholm County Public Health Surveys (2002, 2006, and 2010) | Investigate whether the association between employment status and psychological distress differs between immigrants and (Swedish-born). | Temporary employment | No concerns |

| Sousa et al.,25 Spain | Cross-sectional | 2358 (57.3% males) | ITSAL I and II (Immigration, Labour and Health) Project | Analyse the relationship of legal status and employment conditions with health indicators in foreign born and (Spanish-born workers). | Temporary contract | No concerns |

EPRES: Employment Precariousness Scale; EU-SILC: European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions; HILDA: Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia; SES: socioeconomic status.

The quality of the studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal checklists for cross-sectional and cohort studies as appropriate.24

More specifically, it was unclear which mechanisms were used to re-contact or allow for non-respondents in some studies which relied on repeat survey data collection.

Health outcomes considered

Three health outcomes were explored in the studies: general health, mental wellbeing, and mortality. General health outcomes were included in four studies25,29–31 and were self-reported using a variety of measures; two studies25,31 used a question recommended by the World Health Organization, one study30 used the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12),30 and the remaining study a nationally validated measure.29 Mental wellbeing outcomes were included in nine of the studies.25–28,32–36 Mental health was assessed through validated self-reported measures; the GHQ-12 in four studies,25,27,32,33 the Mental Health Inventory (MHI) derived from the Short Form-36 (SF-36) health questionnaire was used in three studies,26,28,34 the 11-question Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale in one study,36 and the shortened Kessler Psychological Distress (K6) scale in the remaining study.35 Some of these studies also used a ‘threshold’ score to be indicative of clinical measures such as psychological distress, depression, or anxiety.25,27,32,33,35,36 Finally, mortality was considered in the remaining two studies,37,38 one of these studies examined all-cause mortality, non-violent mortality, and violent causes38 and the other study explored premature mortality.37 Both of these studies37,38 assessed mortality using the national (France) computerised databases for recording deaths.

Dimensions and definitions of precarious employment

The definitions of precarious employment (or exposure) used in each of the studies are outlined in Table 1. Precarious employment was defined slightly differently in all studies and despite being a multidimensional construct,5,11 multiple dimensions of precarious employment were only considered in three of the studies,28,32,36 and job insecurity was only explicitly considered in one of these;28 however, temporariness of contract was a constant factor (Table 1). There were differences in the approach to defining employment groups across the studies. Two studies included part-time workers as being in precarious employment.35,36 In some studies, self-employed individuals were excluded;28,34 some studies combined self-employed and permanent employees together;27,29,38 and others treated self-employed individuals as a separate employment category.30 Where unemployed individuals were included, the majority of studies analysed this group as a comparator.26,27,29,33,34,36,38 One study included unemployment within the precarious employment group.32

Inequalities explored

Of the 14 studies included in the synthesis, differences in health outcomes by gender (Table 2) were most frequently identified by authors and discussed in all but two of the studies.32,33

Table 2.

| Main findings for studies examining gender differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, country | Statistical methods | Health measures | Findings | ||

| General health | Mental health | Mortality | |||

| Fiori et al.,26 Italy | Linear regression models | Mental Health Inventory (derived from the SF-36) | – |

Males who reported having the worst mental health were those in atypical employment (B = 2.763), self-employed (B = 2.317), and employed under a fixed-term contract (B = 1.684). Among more educated men, those in a less secure position (Fixed-term: B = 3.789; Atypical: B = 4.498) had a statistically significant higher risk of poor mental health than men in permanent employment. Females who had a fixed-term contract had poorer mental health (B = 2.547), among highly educated women those in fixed-term employment were at a greater risk of poor mental health (B = 2.547). |

– |

| Julià et al.,28 Spain | Poisson regression models/adjusted prevalence rate ratios. Adjusted for age, social class, education status, place of birth, company tenure, and job insecurity. | Mental health inventory (derived from the SF-36) | – | Overall, temporary workers had poorer mental health than permanent workers. However, the association with poor mental health was unexpectedly stronger in permanent workers with high precariousness (aOR = 2.97, 95% CI = 2.25–3.92 in males, aOR = 2.50, 1.70–3.67 in females) than in temporary workers (aOR = 2.17, 95% CI = 1.59–2.96 in males, aOR = 1.81, 95% CI = 1.17–2.78 in females). | – |

| Kachi et al.,35 Japan | Cox proportional hazard ratio (HR) models | K-6 self-rated scale (6 questions, ⩾14 used as cut-off to define Serious Psychological Distress) | – | Exposure to precarious employment in males was associated with a higher risk of serious psychological distress (adjusted HR = 1.79; 95% CI = 1.28–2.51) and was more pronounced in males who were continually employed in precarious arrangements (adjusted HR = 2.32; 95% CI = 1.59–3.40)). In females, there were no statistically significant observations between serious psychological distress and exposure to precarious employment (adjusted HR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.72–1.29). | – |

| Khlat et al.,38 France | Cox survival regression/adjusted hazard ratios (HR) | Death (all-cause, non-violent causes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, violent causes) | – | – | In males, compared to permanent workers, temporary workers had higher all-cause mortality (adjusted HR = 2.21; 95% CI = 1.16–4.24), non-violent mortality (adjusted HR = 2.22; 95% CI = 1.12–4.40), in particular cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR = 3.56; 95% CI = 1.02–12.44). There was no significant difference for all-cause mortality observed in females (adjusted HR = 1.28; 95% CI = 0.45–3.62). |

| Kim et al.,36 South Korea | Multivariate logistic regression | Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (11-question version) | – | In both males and females, continual precarious employment showed no association with new-onset of depressive symptoms (Males: aOR = 1.59; 95% CI = 0.90–2.81; Females: aOR = 1.50; 95% CI = 0.69–3.25). In females, new-onset depressive symptoms were higher in any employment transitions that included precarious employment (permanent-precarious: aOR = 2.88; 95% CI = 1.24–6.66; precarious-permanent: aOR = 2.57; 95% CI = 1.20–5.52). These observations were not statistically significant in males (permanent-precarious: aOR = 1.19; 95% CI = 0.57–2.50; precarious-permanent: aOR = 0.76; 95% CI = 0.39–1.46). |

– |

| Minelli et al.,29 Italy | Fixed effects ordered logit model | SALUT (5-point Likert scale. Ranging from 1–‘very poor’ to 5–‘excellent’. | Self-reported health scores were lower in male temporary workers (compared to permanent employees) aged 15–40 years, but not females. Male first-job seekers were also observed to have lower self-reported health scores. | – | – |

| Niedhammer et al.,37 France | Hazard ratios (adjusted for SES, age, lifestyle factors, work conditions, social support) | Premature mortality (death before the age of 70 years), all-cause mortality, total mortality. | – | – | In temporary workers, premature mortality was adjusted HR = 1.80 (95% CI = 1.24–2.63) times higher than in permanent employees. This observation was far more pronounced in males (adjusted HR = 2.23; 95% CI = 1.42–3.51) than females (adjusted HR = 1.11; 95% CI = 0.56–2.20). |

| Pirani and Salvini,31 Italy | Marginal structural model (adjusted for age, marital status, area of residence, education, financial situation, occupation, pre-existing condition) | Poor self-rated health combined of ‘very poor’, ‘poor’ and ‘fair’ responses. (WHO suggested question ‘How is your health in general?’). | In females, compared to permanent employment, poor self-rated health greater in temporary contracts (aOR = 4.95; 95% CI = 2.10–11.69). This observation was present in transitions from permanent–temporary (aOR = 5.56; 95% CI = 1.86–16.61) and consistently temporary (aOR = 4.28; 95% CI = 1.83–10.02). In males, none of these observations were statistically significant. Poor SRH in temporary employment compared to permanent (aOR = 2.06; 95% CI = 0.76–5.57). | – | – |

| Richardson et al.,34 Australia | Random effects panel model | Mental Health Inventory (derived from the SF-36). | – | This study found almost no evidence that flexible employment harms mental health. Among the employed, only males educated to diploma level employed either fixed-term full-time (coefficient: −2.479) or part-time (coefficient: −0.928) has lower mental health scores. | – |

| Samuelsson et al.,30 Sweden | Multiple linear regression | GHQ–six-item version. | One significant interaction was observed; gender moderated the association between temporary employment and poor SRH. Stratified analyses (by gender) indicated that temporary employment was significantly associated in males (β = 0.11, p < .05) but not females (β = −0.05, NS). | – | – |

| Sidorchuk et al.,27 Sweden | Crude and adjusted odds ratios (aOR). Adjusted for socioeconomic position, disposable family income, and survey year. | GHQ-12. Below 3 good mental health, ⩾3 poor mental health |

– | When compared to permanently employed counterparts, the odds of experiencing psychological distress was higher in males (aOR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.15–1.59) than females (aOR = 1.17; 95% CI = 1.05–1.31). | – |

| Sousa et al.,25 Spain | Prevalences, crude and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) | Poor self-rated health combined of ‘very poor’, ‘poor’ and ‘fair’ responses. GHQ-12 (Mental Health). Below 3 good mental health, ⩾3 poor mental health |

In males, poor self-rated health was not strongly influenced by contract arrangements. Compared to Spanish born, permanent workers, females at highest risks of poor self-rated health are foreign-born workers who have been in Spain >3 years with no employment contract (aOR = 4.63; 95% CI = 1.95–10.97) or temporary contract (aOR = 2.36; 95% CI = 1.13–4.91). |

Compared to Spanish born, permanent workers, male foreign-born workers on temporary contracts who have lived in Spain for less than 3 years were at the highest risk of poor mental health (aOR = 1.96; 95% CI = 1.13–3.38). Compared to Spanish born, permanent workers, females at highest risks of poor mental health are foreign-born workers who have been in Spain >3 years with no employment contract (aOR = 1.93; 95% CI = 0.95–3.92). |

– |

SF-36: Short Form-36 (SF-36) health questionnaire; B: unstandardised coefficient; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; K6: shortened Kessler Psychological Distress scale; WHO: World Health Organization; SRH: self-rated health; GHQ: General Health Questionnaire; β: standardised beta values; SES: socioeconomic status.

The exposure of precarious employment on health outcomes experienced by younger individuals (Table 3) was considered in three studies26,29,32 and only three studies25,27,33 considered health outcomes for migrant workers (Table 4).

Table 3.

| Main findings for studies examining young individuals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Country | Statistical methods | Health measures | Findings | ||

| General health | Mental health | Mortality | |||

| Canivet et al.,32 Sweden | Data presented as percentages and age-adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR) | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). ‘GHQ-caseness’ defined as a scoring of 2 or higher. |

– | An employment trajectory that included precarious employment, the IRR for poor mental health was 1.4 (95% CI = 1.1–2.0). The Population Attributable Fraction (PAR) for poor mental health was 18%. | – |

| Fiori et al.,26 Italy | Linear regression models | Mental Health Inventory (MHI). For ease of interpretation, the MHI was then transformed into a 0–100 scale using a transformation formula. | – | Those seeking their first job were at greater risk of experiencing poor mental health (Males: B = 5.158; Females: B = 2.499). | – |

| Minelli et al.,29 Italy | Fixed effects ordered logit model | SALUT (5-point Likert scale). Ranging from 1–‘very poor’ to 5–‘excellent’. | Self-reported health (SRH) was lower in temporary workers aged 15–40 years. First-job seekers in this younger age bracket also reported lower SRH. | – | – |

IRR: incidence rate ratios; GHQ: General Health Questionnaire; CI: confidence interval; PAR: population attributable fraction; MHI: Mental Health Inventory; B: unstandardised coefficient; SRH: self-reported health.

Table 4.

| Main findings for studies examining migrant workers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Country | Statistical methods | Health measures | Findings | ||

| General health | Mental health | Mortality | |||

| Robert et al.,33 Spain | Crude and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) | GHQ-12 (Spanish language version). Below 3 good mental health, ⩾3 poor mental health. |

– | Increased risk of poor mental health (aOR) in employment with no contract (2.24; 95% CI = 0.76–6.67), from employment to unemployment (3.62; 95% CI = 1.64–7.96), decreased income (2.75; 95% CI = 1.08–7.00), and continuous low income (2.73; 95% CI: 0.98–7.62). | – |

| Sidorchuk et al.,27 Sweden | Crude and adjusted odds ratios (aOR). | GHQ-12. Below 3 good mental health, ⩾3 poor mental health. Outcome severity cut-off score of 7. |

– | Increased risk of psychological distress in immigrants who are temporary employed (compared to permanently or self-employed). Crude: 1.86 (95% CI = 1.57–2.20), aOR: 1.60 (95% CI = 1.34–1.92). More apparent in refugees (aOR = 1.71; 95% CI = 1.37–2.15) than non-refugees (aOR = 1.36; 95% CI = 1.01–1.81). | – |

| Sousa et al.,25 Spain | Prevalences, crude and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) | Poor self-rated health combined of ‘very poor’, ‘poor’ and ‘fair’ responses. GHQ-12 (Mental Health). Below 3 good mental health, ⩾3 poor mental health. |

Compared to Spanish born, permanent workers, females at highest risks of poor self-rated health are foreign-born workers who have been in Spain >3 years with no employment contract (aOR = 4.63; 95% CI = 1.95–10.97) or temporary contract (aOR = 2.36; 95% CI = 1.13–4.91). | Compared to Spanish born, permanent workers, females at highest risks of poor mental health are foreign-born workers who have been in Spain >3 years with no employment contract (aOR = 1.93; 95% CI = 0.95–3.92). Compared to Spanish born, permanent workers, male foreign-born workers on temporary contracts who have lived in Spain for less than 3 years were at the highest risk of poor mental health (aOR = 1.96; 95% CI = 1.13–3.38). |

– |

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; GHQ: General Health Questionnaire; CI: confidence interval.

Identification of confounders and covariates

The papers included in this summary all list a number of confounders or covariates, which were considered and adjusted for in the statistical models. Education, gender, deprivation, and financial situation were identified as potential confounders in over half of the included studies and some of the studies28,30,31,33,35,37 also adjusted for occupational factors such as job role, company size, and workplace characteristics. The most common variable identified was age, which was adjusted for in statistical calculations in all but one study.30 Two studies31,34 make reference to the prevalence of precarious employment being higher in younger age groups, two studies29,32 make reference to age having an effect on health, and one study36 explicitly stated age as a confounding variable. The remaining studies did not have an open rationale for adjusting for age.

Discussion

One of the fundamental principles of public health is to address health inequalities that persist, including those within the wider determinants of health – such as employment. This scoping review further examines three subpopulations (young individuals, migrant workers, females) that have been identified in the literature to be at an unequal exposure to precarious employment and explores the impact on health. We have structured the discussion to mainly focus on the recent literature featuring these three subpopulations. Finally, we appraise what the current literature is missing and suggest some direction(s) for future research.

Gender differences

As previously commented upon in the ‘Results’ section, the majority of included studies (n = 12) examined gender differences in health outcomes in relation to precarious employment exposure (Table 2). The research gap reported in 2007 has been somewhat filled a decade later.17 Mental wellbeing was explored in seven studies,25–28,34–36 self-rated general health in four studies,25,29–31 and two studies explored mortality.37,38 In the seven studies that examined mental wellbeing, four of these reported poorer mental health outcomes in both men and women employed in precarious employment.25–28 Some studies reported up to and over a twofold increased risk of poorer mental health,26,28 and this was observed in one study aligned to the employment precariousness, irrespective of contract type.28 Higher educated men in fixed-term or atypical employment exhibited worse mental health outcomes than their equally educated female counterparts employed in these contract arrangements.26 In two of three studies, it was observed that men in precarious employment were at greater risk of poorer mental health compared to women,34,35 whereas one study demonstrated women at greater risk than men.36 Furthermore, in men, risk of psychological distress was higher in those employed continuously in precarious employment,35 but this did not increase the risk of new-onset depressive symptoms.36

Within the included literature, there were inconsistencies reported in terms of self-reported health. Self-reported health in males employed in precarious employment was worse compared to permanent employment in two studies,29,30 but there were no differences reported in the other two studies.25,31 In women, some studies observed poorer self-reported health in temporary workers that was four times higher compared to permanent workers,25,31 although in the other studies there were no reported differences.29,30 It was interesting that in the four studies that examined self-reported health, there were no consistent observations in both men and women reporting poorer self-reported health. The final health outcome that examined gender differences was mortality. Compared to their counterparts in permanent employment, men in temporary employment at baseline had higher all-cause mortality, in particular cardiovascular mortality (adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 3.56; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.02–12.44) when followed up 13 years later.38 These findings were mediated by pre-existing health conditions and lifestyle factors.38 In a similar follow-up period, and using the same data source,37 it was observed that premature mortality was far more pronounced in men (adjusted HR = 2.23; 95% CI = 1.42–3.51) that had worked in precarious employment than women (adjusted HR = 1.11; 95% CI = 0.56–2.20).

Young individuals

We identified three studies26,29,32 that met our inclusion criteria and examined the impact of precarious employment on young individuals (Table 3). Two of these studies26,32 explored the mental health outcomes associated with precarious employment and the other study examined general health.29 With regard to the quality of these studies, we had only similar minor concerns about loss to follow-up for the mental health outcomes,26,32 but no such concerns for the study exploring self-reported health.29 Overall, one of the cohort studies calculated the incidence rate ratio of experiencing poor mental health to be 1.4 (95% CI = 1.1–2.0) for those individuals with any exposure to precarious working arrangements in their employment history.32 Self-reported health was also found to be lower in young individuals employed in temporary employment compared to those in permanent employment.29 Those seeking their first job were also at a greater risk of experiencing poorer general and mental health.26,29 The observations concerning seeking first employment have important connotations especially when considering education levels.39 Employment requiring higher levels of qualifications is often secure and protected, whereas employment opportunities with no such educational requirements has the tendency to be temporary and less regulated, that is, precarious.3,39 It was therefore interesting to observe that the more educated individuals who had fixed-term positions had poorer mental wellbeing.26

It should be acknowledged that five of the other studies included in this review25,28,31,33,36 explored age as a demographic characteristic when presenting their results on the sample distribution of precarious employment. One of these studies demonstrated that temporary contracts were more prevalent in the younger age groups,31 whereas another study identified that younger individuals even in permanent positions also experienced precarious employment.28 None of these studies explored the health outcomes associated with precarious employment by age group. This clearly demonstrates that there is existing and available data, yet to be utilised to examine the extent of health inequalities experienced by the younger demographic. In addition, the cohort study undertaken by Samuelsson et al.30 followed up individuals from age 30 up to 42 years, although the analysis did not compare age groups, the findings still have relevance for the younger age groups.

Migrant workers

We identified three studies that examined the health impacts on migrant workers (Table 4), all three of which focused on mental health outcomes,25,27,33 with one study also exploring self-rated health.25 There were no concerns about the quality of the cross-sectional studies,25,27 with only minor concerns about loss to follow-up in the cohort study.33 One of the major consistencies, and therefore strengths, within these studies is that all of them assessed mental wellbeing using the 12-item version of the GHQ-12 and used the same ‘caseness’ threshold of 3 to determine poor mental health. There was a greater risk of poor mental wellbeing in migrant workers in precarious employment (compared to migrant workers in permanent employment) ranging from aOR = 1.60 (95% CI: 1.34–1.92)27 up to aOR = 2.24 (95% CI: 0.76–6.67).33 Compared to native men in permanent employment, these risks were even greater in those with refugee status (men: aOR = 2.39 (95% CI: 1.32–4.30); women: aOR = 3.71 (95% CI: 2.31–5.95)).27 Those who experienced components associated with precarious employment such as job loss (aOR = 3.62 (95% CI: 1.64–7.96)) and decreased income (aOR = 2.75 (95% CI: 1.08–7.00)) were found to be at even greater risk of poor mental health.33 In addition, working without a contract and being resident in a foreign country for less than 3 years also increased the risk of both poor mental and general health.25 Notably, one study observed that female migrant workers in non-permanent employment demonstrated poorer self-reported health, but men did not.25

Gaps in literature and next steps

Although being disproportionately at risk of exposure to precarious employment, there are limited studies that explore the health implications of precarious employment on young individuals. Our review echoes a recent scoping study on this demographic group, which explored health outcomes experienced through both unemployment and precarious employment and proposed the need for further longitudinal research with a focus on gender outcomes and third factor (e.g. personality traits, job, and family histories) considerations.15 Now, more than ever, with the probable economic and employment considerations which result from the global Covid-19 pandemic, it is important this new youthful generation, particularly vulnerable in a likely unstable labour market,15 do not experience the same enduring detrimental consequences to mental wellbeing as their predecessors.3,40 Despite inequities that persist with exposure to precarious employment in migrant workers, there were only a small number of studies included in our review. We acknowledge that some qualitative research has been undertaken in this subpopulation to explore their experiences,41 so understanding in the migrant worker group may not be as limited as the knowledge surrounding young individuals.

Only one of the included studies28 explicitly calculated employment precariousness using the Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES), all other studies defined precarious employment as either temporary, fixed-term, or atypical contract arrangements which is a limitation of the evidence base previously reported by others.5 The literature also contains inconsistencies when grouping employment and contract types together to create reference categories. Another inconsistency in approach was the inclusion or exclusion of those who are in self-employment, since the EPRES explicitly excludes self-employment from the calculation.10,11

It should also be acknowledged that some support structures such as a stable relationship,35,42 perceived job control,43 managerial support,44 or even the personal choice of working in precarious arrangements45 can somewhat negate (or buffer) some of the adverse health impacts associated with precarious employment. Marital status or living arrangements were adjusted for in five studies;26,31,34–36 however, none of the other aforementioned buffering factors were fully evident within the included literature.

In terms of global health implications and research opportunities, the included studies all took place in developed countries. It was surprising that no studies undertaken in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, or Germany (four of the G7 countries) met our inclusion criteria. Nevertheless, this highlights a lack of understanding to both the extent of precarious employment in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and the associated impacts on population health in these countries. There was also a reliance within the current literature on self-reported measures for health. One disadvantage to this approach is that there can be discrepancies between self-reported health and biomarker data, that is, lower perceived feelings of general health do not necessarily result in worse health biomarkers.46 The recent advancements in data linkage between health and administrative records presents an opportunity to reduce the reliance of self-reported measures and use medical data to examine the impact of precarious employment on health outcomes.

There are a number of limitations to state in our review. We decided not to include workplace injuries as a health outcome in this review. We acknowledge that a body of evidence exists to suggest that precarious employment is associated with hazardous working conditions. However, a systematic review on precarious employment and occupational accidents and injuries has recently been undertaken47 and we felt including injuries as a health outcome in our review would not add to this recent publication. Only peer-reviewed published literature in English was included in our review; therefore, grey literature and research published in other languages were not considered, potentially excluding some current evidence from our overview.

Conclusion

Our review further explores an emerging social determinant of health;6 this time with a scoping focus on the inequalities presented in the current, good quality literature. We examined the impacts of precarious employment on health in three subpopulation differences: young individuals, migrant workers, and gender differences. We found an abundance of literature exploring gender differences in health; there were clear inconsistencies in relation to self-reported health, and males with exposure to precarious employment were more at risk of mortality, including premature mortality. On the whole, poorer mental wellbeing was associated with precarious employment in both males and females, although continual exposure to precarious employment appeared to be more detrimental to males. Unfortunately, there was limited evidence examining the health impacts on young individuals and migrant workers, and it is these two subpopulations that are exposed to precarious employment most often. More research needs to be undertaken to fully understand the implications of such contract arrangements on both short- and long-term health for young individuals and migrant workers, particularly to compare pre- and post-Covid pandemic impact. Furthermore, there is a need for drivers of health equity, particularly policy coherence, to consider the policy and legislative impact of precarious employment trends, particularly on the health and wellbeing of vulnerable subgroups of the population3 to ensure that they are not being left behind.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to Ms Ella Sykes who assisted with the initial database searches and title screening.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: No research permissions were required for this scoping review.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Orcid Ids: Benjamin J Gray  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1548-707X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1548-707X

Amy Hookway  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1191-2198

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1191-2198

Contributor Information

BJ Gray, Knowledge Directorate, Research and Evaluation Division, Public Health Wales, Number 2 Capital Quarter, Tyndall Street, Cardiff CF10 4BZ, UK.

CNB Grey, Research and Evaluation Division, Public Health Wales, Cardiff, UK.

A Hookway, Observatory Evidence Service, Public Health Wales, Cardiff, UK.

L Homolova, Research and Evaluation Division, Public Health Wales, Cardiff, UK.

AR Davies, Research and Evaluation Division, Public Health Wales, Cardiff, UK.

References

- 1. Van Aerden K, Puig-Barrachina V, Bosmans K, et al. How does employment quality relate to health and job satisfaction in Europe? A typological approach. Soc Sci Med 2016;158:132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Noordt M, IJzelenberg H, Droomers M, et al. Health effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occup Environ Med 2014;71(10):730–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Healthy, Prosperous Lives For All: The European Health Equity Status Report (2019). Available online at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/health-equity-status-report-2019 (2019, last accessed 20 May 2020).

- 4. Caldbick S, Labonte R, Mohindra KS. et al. Globalization and the rise of precarious employment: the new frontier for workplace health promotion. Glob Health Promot 2014;21(2):23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benach J, Vives A, Tarafa G, et al. What should we know about precarious employment and health in 2025? Framing the agenda for the next decade of research. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45(1):232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benach J, Vives A, Amable M. et al. Precarious employment: understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:229–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wickramasekara P. Globalisation, international labour migration and the rights of migrant workers. Third World Q 2008;29(7):1247–64. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buchholz S, Hofacker D, Mills M, et al. Life courses in the globalization process: the development of social inequalities in modern societies. Eur Sociol Rev 2009;25(1):53–71. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karanikolos M, Mladovsky P, Cylus J, et al. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet 2013;381:1323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vives A, Moncada S, Llorens C, et al. Measuring precarious employment in times of crisis: the revised Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES) in Spain. Gaceta Sanitaria 2015;29:8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vives A, Amable M, Ferrer M, et al. The Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES): psychometric properties of a new tool for epidemiological studies among waged and salaried workers. Occup Environ Med 2010;67(8):548–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reneflot A, Evensen M. Unemployment and psychological distress among young adults in the Nordic countries: a review of the literature. Int J Soc Welf 2014;23(1):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Benach J, Muntaner C, Chung H, et al. Immigration, employment relations, and health: developing a research agenda. Am J Ind Med 2010;53(4):338–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Puig-Barrachina V, Vanroelen C, Vives A, et al. Measuring employment precariousness in the European working conditions survey: the social distribution in Europe. Work 2014;49(1):143–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vancea M, Utzet M. How unemployment and precarious employment affect the health of young people: a scoping study on social determinants. Scand J Public Health 2017;45(1):73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agudelo-Suárez A, Gil-González D, Ronda-Pérez E, et al. Discrimination, work and health in immigrant populations in Spain. Soc Sci Med 2009;68(10):1866–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Menéndez M, Benach J, Muntaner C, et al. Is precarious employment more damaging to women’s health than men’s? Soc Sci Med 2007;64(4):776–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Julià M, Belvis F, Vives A, et al. Informal employees in the European Union: working conditions, employment precariousness and health. J Public Health 2019;41:e141–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laszlo KD, Pikhart H, Kopp MS, et al. Job insecurity and health: a study of 16 European countries. Soc Sci Med 2010;70(6):867–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giatti L, Barreto SM, César CC. Household context and self-rated health: the effect of unemployment and informal work. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62(12):1079–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cezar-Vaz MR, de Almeida MCV, Bonow CA, et al. Casual dock work: profile of diseases and injuries and perception of influence on health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11(2):2077–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davies AR, Homolova L, Grey CNB, et al. Health and mass unemployment events-developing a framework for preparedness and response. J Public Health 2019;41(4):665–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z. (eds) Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. Available online at: https://joannabriggs.org/critical-appraisal-tools [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sousa E, Agudelo-Suárez A, Benavides FG, et al. Immigration, work and health in Spain: the influence of legal status and employment contract on reported health indicators. Int J Public Health 2010;55(5):443–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fiori F, Rinesi F, Spizzichino D, et al. Employment insecurity and mental health during the economic recession: an analysis of the young adult labour force in Italy. Soc Sci Med 2016;153:90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sidorchuk A, Engström K, Johnson CM, et al. Employment status and psychological distress in a population-based cross-sectional study in Sweden: the impact of migration. BMJ Open 2017;7(4):e014698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Julià M, Vives A, Tarafa G, et al. Changing the way we understand precarious employment and health: precarisation affects the entire salaried population. Saf Sci 2017;100:66–73. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Minelli L, Pigini C, Chiavarini M, et al. Employment status and perceived health condition: longitudinal data from Italy. BMC Public Health 2014;14(1):946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Samuelsson A, Houkes I, Verdonk P, et al. Types of employment and their associations with work characteristics and health in Swedish women and men. Scand J Public Health 2012;40(2):183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pirani E, Salvini S. Is temporary employment damaging to health? A longitudinal study on Italian workers. Soc Sci Med 2015;124:121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Canivet C, Bodin T, Emmelin M, et al. Precarious employment is a risk factor for poor mental health in young individuals in Sweden: a cohort study with multiple follow-ups. BMC Public Health 2016;16(1):687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robert G, Martínez JM, García AM, et al. From the boom to the crisis: changes in employment conditions of immigrants in Spain and their effects on mental health. Eur J Public Health 2014;24(3):404–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Richardson S, Lester L, Zhang G. Are casual and contract terms of employment hazardous for mental health in Australia? J Ind Relations 2012;54(5):557–78. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kachi Y, Otsuka T, Kawada T. Precarious employment and the risk of serious psychological distress: a population-based cohort study in Japan. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40(5):465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim SS, Subramanian SV, Sorensen G, et al. Association between change in employment status and new-onset depressive symptoms in South Korea – A gender analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health 2012;38(6):537–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Niedhammer I, Bourgkard E, Chau N. Occupational and behavioural factors in the explanation of social inequalities in premature and total mortality: a 12.5-year follow-up in the Lorhandicap study. Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Khlat M, Legleye S, Falissard B, et al. Mortality gradient across the labour market core–periphery structure: a 13-year mortality follow-up study in north-eastern France. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2014;87(7):725–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de Lange M, Gesthuizen M, Wolbers MHJ. Youth labour market integration across Europe: the impact of cyclical, structural, and institutional characteristics. Eur Soc 2014;16(2):194–212. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rathmann K, Pförtner TK, Hurrelmann K, et al. The great recession, youth unemployment and inequalities in psychological health complaints in adolescents: a multilevel study in 31 countries. Int J Public Health 2016;61(7):809–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Panikkar B, Brugge D, Gute DM, et al. ‘They see us as machines’: The experience of recent immigrant women in the low wage informal labor sector. PLoS ONE 2015;10(11):e0142686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cortès-Franch I, Escribà-Agüir V, Benach J, et al. Employment stability and mental health in Spain: towards understanding the influence of gender and partner/marital status. BMC Public Health 2018;18(1):425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vander Elst T, De Cuyper N, Baillien E, et al. Perceived control and psychological contract breach as explanations of the relationships between job insecurity, job strain and coping reactions: towards a theoretical integration. Stress Health 2016;32(2):100–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ravalier JM, Fidalgo AR, Morton R, et al. The influence of zero-hours contracts on care worker well-being. Occup Med 2017;67(5):344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Santin G, Cohidon C, Goldberg M, et al. Depressive symptoms and atypical jobs in France, from the 2003 Decennial Health Survey. Am J Ind Med 2009;52(10):799–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johansson E, Böckerman P, Lundqvist A. Self-reported health versus biomarkers: does unemployment lead to worse health? Public Health 2020;179:127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Koranyi I, Jonsson J, Rönnblad T, et al. Precarious employment and occupational accidents and injuries – a systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 2018;44:341–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]