Figure 1.

Small Differences in Virtual Environments Lead to Larger Spatial Remapping in the DG Than in CA1

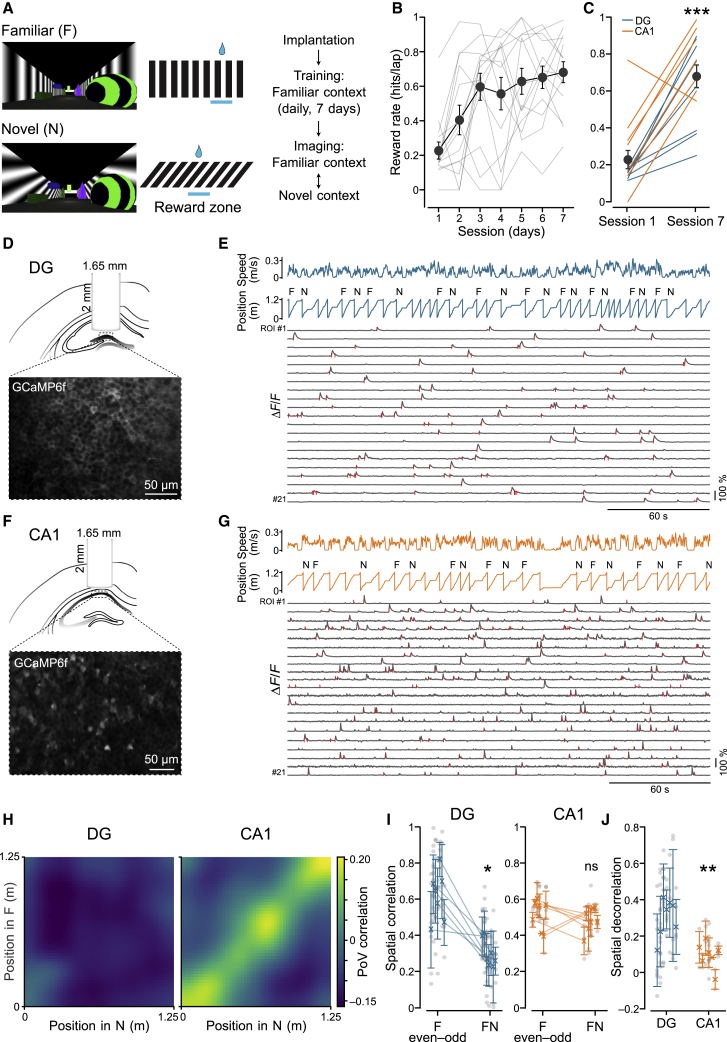

(A) Left: views of the familiar (F; vertical grating) and novel (N; oblique grating) virtual reality environments. Center: schematic indicating the reward locations along the track. Right: experimental timeline.

(B) Quantification of behavioral performance, measured as reward rate (hits per lap), during the training sessions in the F virtual environment. Grey lines represent performance of individual animals, whereas large circles indicate mean ± SEM across all animals (n = 14; one-way repeated-measures (RM) ANOVA, F = 7.78, p = 1 × 10−6; DG: n = 7 mice; one-way RM ANOVA, F = 3.08, p = 0.015; CA1: n = 7 mice; one-way RM ANOVA, F = 5.27, p = 0.0005).

(C) Comparison of behavioral performance during session 1 and session 7 for mice implanted in the dentate gyrus (DG, blue; reward rate [hits/lap]: day 1, 0.15 ± 0.01; day 7, 0.60 ± 0.09; n = 7; Wilcoxon test, t = 28, p = 0.015) or CA1 (orange; day 1, 0.30 ± 0.09; day 7, 0.77 ± 0.06; n = 7; Wilcoxon test, t = 26, p = 0.03; all animals: day 1, 0.23 ± 0.05; day 7, 0.68 ± 0.06; Wilcoxon test, t = 99, p = 0.0006).

(D) Top: schematic of the imaging implant in the DG. Bottom: representative fluorescence image of GCaMP6f-expressing DG neurons in vivo.

(E) Representative imaging session showing animal speed, position along the track, and context type for each lap (F or N). Traces at the bottom show fluorescence extracted from example regions of interest (ROIs) in the DG. Significant transients during running periods are indicated by red tick marks.

(F and G) Same as in (D) and (E) but for CA1.

(H) Spatial population vector (PoV) correlation matrices. PoV correlations were computed for each spatial bin in the N environment (x axis) with each bin in the F environment (y axis). Note the absence of distinct high correlations in the DG (left) throughout the matrix. In contrast, correlations are high along the diagonal in CA1, indicating that neuronal activities are correlated at corresponding positions in F and N along the linear track.

(I) Correlations between mean spatial activity maps across recording sessions within the F environment (even-odd laps) and between different environments (FN) in the DG (left; spatial correlation: F even-odd, 0.62 ± 0.05; FN, 0.30 ± 0.03, n = 7 mice; Wilcoxon test, t = 0, p = 0.018) and CA1 (right; spatial correlation: F even-odd, 0.51 ± 0.03; FN, 0.48 ± 0.02, n = 7 mice; Wilcoxon test, t = 11, p = 0.61). Symbols with error bars represent mean ± SEM of individual animals. Gray circles represent recording sessions.

(J) Spatial decorrelation, quantified as the difference between spatial correlations within the F environment (even-odd) and between different environments (FN) in the DG and CA1. Circles indicate single recorded sessions from different animals (spatial decorrelation: DG, 0.32 ± 0.06, n = 7; CA1, 0.03 ± 0.05, n = 7; linear mixed model [LMM], p = 0.002). Same symbols as in (I).

∗p < 0.05. ∗∗p < 0.01. ∗∗∗p < 0.001. See also Figures S1A–S1F.