Abstract

Objectives:

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. In 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography in adults meeting certain criteria. This study seeks to assess lung cancer screening uptake in three health systems.

Setting:

This study was part of a randomized controlled trial to engage underserved populations in preventive care and includes 45 primary care practices in eight states.

Methods:

Practice and clinician characteristics were manually collected. Lung cancer was measured from electronic health record data. A generalized linear mixed model was used to assess characteristics associated with screening.

Results:

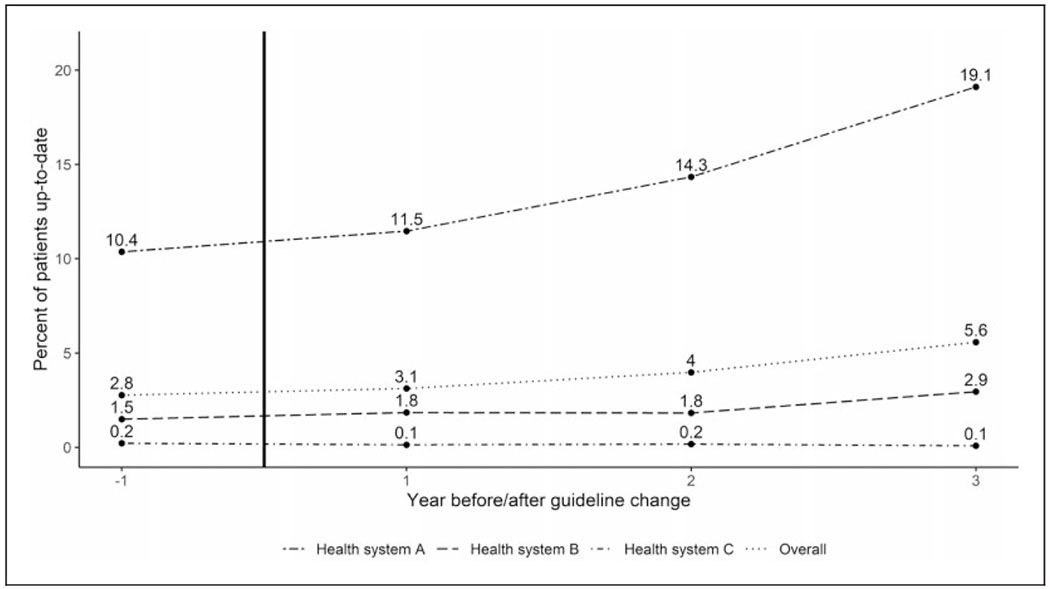

Patient records between 2012 and 2016 were examined. Lung cancer screening uptake overall increased only slightly after the guideline change (2.8–5.6%, p < 0.01). One health system did not show an increase in uptake (0.2–0.1%, p = 0.32), another had a clinically insignificant increase (1.5–2.9%, p < 0.01), and the third nearly doubled its higher baseline screening rate (10.4–19.1%, p < 0.01). Within the third health system, patients more likely to be screened were older, male, had more comorbid conditions, visited the office more frequently, were seen in practices closer to the screening clinic, or were uninsured or covered by Medicare or Medicaid.

Conclusions:

Certain patients appeared more likely to be screened. The only health system with increased lung cancer screening explicitly promoted screening rather than relying on clinicians to implement the new guideline. Systems approaches may help increase the low uptake of lung cancer screening.

Keywords: Lung cancer, cancer screening, guideline adherence, preventive health services, healthcare delivery

Introduction

Although lung cancer incidence is declining, it remains the leading cause of US cancer-related deaths.1 In 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated the lung cancer screening guidelines to recommend annual screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for adults aged 55–80 with a 30 pack-year smoking history who are current smokers or have quit within the last 15 years.2–4 Screening with LDCT is especially sensitive to detecting early stage lung cancer, at which point patients have a better prognosis and surgical resection is possible.3

Proper adoption of screening guidelines for lung cancer would prevent about 12,000 deaths annually.5 Despite these known benefits, the National Health Interview Survey estimated that lung cancer screening only increased from 3.3% in 2010 to 3.9% in 2015.2,6 This low estimate is reasonable considering that private health insurers were not required to cover lung cancer screening until the Affordable Care Act went into effect in 2015 and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) did not begin covering lung cancer screening until 2016.7,8 There are several additional explanations for why screening rates are so low. Complex eligibility criteria can discourage providers from properly identifying eligible patients and practices from creating electronic alerts, reminders, and overdue care reports.9–11 Patients and clinicians are concerned about high rates of false positives and extra-pulmonary findings.2,9,12–15 CMS coverage requires documentation of shared decision-making prior to screening, which is time consuming.7 Some clinicians disagree with the suggested age to start and stop screening, the frequency of screening, the number of times a patient should be screened, and the effectiveness of LDCT.6,7,9,13,14,16–18

Methods

This retrospective observational analysis aimed to assess practice, clinician, and patient factors influencing the uptake of the USPSTF lung cancer screening recommendation. Data had been previously collected as part of an ongoing trial to promote engaging underserved populations in preventive care online.19

Study setting

All primary care practices within three health systems participated, for a total of 45 primary care practices in eight states. These health systems were purposefully selected for their diversity.19 Nine practices were from a health system composed of urban safety net practices with high proportions of uninsured and Black patients (health system A). Twelve practices were from a health system of mainly suburban private practices primarily serving an affluent, insured, and educated population (health system B). The 24 remaining practices were from a nonprofit network of Federally Qualified Health Centers and community health centers in rural, suburban, urban, and academic settings (health system C). While health system C represents five independent health systems, they share a common electronic health record (EHR) and systems to promote recommended care, and are thus considered one health system for the purposes of this analysis.

Patients

All patients with an office visit in the health systems between December 2012 and December 2016, one year before and three years after the USPSTF guideline change, were included for this analysis. Because it was not possible to verify USPSTF criteria based on available data, adults aged 55–80 who were current smokers were considered eligible for lung cancer screening.

Measurements

EHR data were used to assess patient characteristics, eligibility for screening, and up-to-datedness. Patient information extracted from the EHR included age, gender, race, ethnicity, language, insurance, diagnoses, visit dates, test dates, test results, clinician seen, and smoking status. Patients were considered up-to-date each year if they had any variant of a chest CT, low dose or standard, regardless of indication in the 15 months prior to an office visit. Insurance and race were used as surrogates to define underserved patients.

Staff were interviewed at each practice to assess clinician and practice characteristics. Clinician characteristics (age, specialty, year of residency completion, race/ethnicity, and attending status) and practice characteristics (location, number of patients, year obtained EHR, year obtained portal, percent of patients using portal, patient centered medical home status, and patient insurance distribution) were reported by each practice’s office manager as part of a larger clinical trial.19 The Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics were summarized overall and by health system. Frequencies and percentages of patients up-to-date with screening were calculated by year. Generalized linear mixed models were used to evaluate change over time accounting for practice variability and to conduct subgroup analyses within health system A for differences in being up-to-date based on patient, clinician, or practice factors. Results were summarized with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) and R version 3.5.0 were used for analyses.20,21

Results

A total of 14,218 patients were included in the analysis (Table 1). The majority of patients in health system A were Black (59.6%) compared to health systems B and C, which had a majority of white patients (80.8 and 79.6%, respectively). More patients were covered through Medicare in health systems A (50.9%) and C (42.6%), while most patients had commercial insurance in health system B (90.4%). Health system C had the greatest proportion of current smokers, followed by health system A and health system B (20.2, 14.7, and 7.7%, respectively, in the year prior to the guideline change). Smoking prevalence was fairly stable year to year.

Table 1.

Characteristics of current smokers by health system.

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 14,218) | Health system A (N = 2797) | Health system B (N = 5791) | Health system C (N = 5630) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | Asian | 263 (2.0%) | 7 (0.2%) | 221 (4.3%) | 35 (0.6%) |

| Black | 3052 (22.7%) | 1664 (59.6%) | 345 (6.8%) | 1043 (18.9%) | |

| White | 9605 (71.5%) | 1076 (38.5%) | 4132 (80.8%) | 4397 (79.6%) | |

| Other | 512 (3.8%) | 47 (1.7%) | 413 (8.1%) | 52 (0.9%) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 414 (3.2%) | 24 (0.9%) | 145 (3.1%) | 245 (4.5%) |

| Gender | Female | 7073 (49.8%) | 1584 (56.6%) | 2654 (45.8%) | 2835 (50.4%) |

| Age (SD) | 61.8 (5.8) | 62.2 (5.9) | 61.6 (5.6) | 61.8 (5.9) | |

| Insurance | Commercial | 2454 (42.5%) | 331 (26.8%) | 1567 (90.4%) | 556 (19.8%) |

| Medicaid | 595 (10.3%) | 112 (9.1%) | 20 (1.1%) | 463 (16.5%) | |

| Medicare | 1970 (34.1%) | 629 (50.9%) | 147 (8.5%) | 1194 (42.6%) | |

| Uninsured | 753 (13.1%) | 163 (13.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 590 (21.1%) |

Age and insurance data were collected in the year preceding the guideline change. These proportions did not change meaningfully over the four-year study period.

Overall rates of lung cancer screening using CT were low, increasing from 2.8% of eligible patients the year prior to the 2013 USPSTF recommendation to 5.6% three years after the recommendation (p < 0.01, Figure 1). Prior to the USPSTF recommendation, screening rates were low in health systems B and C (Figure 1) and did not change meaningfully after the recommendation. The screening rate for health system B increased only from 1.5 to 2.9% (p < 0.01) and did not change within health system C (from 0.2 to 0.1%, p = 0.32). The screening rate was higher at baseline in health system A and nearly doubled after three years (10.4% versus 19.1%, p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Lung screening rates in three health systems. Percent of patients up-to-date for each health system and overall before (year – 1) and after (years 1–3) the guideline change in 2013, which is indicated by the vertical black line. Screening rates start and remain low for health system C. Health system B sees a small but not meaningful increase in the last year of screening. Health system A starts at a much higher proportion of patients up-to-date and this rate almost doubles over the study period.

The model assessing factors associated with patients being up-to-date with screening only included health system A because it was the only health system with meaningful screening uptake (Table 2). Older patients, male patients, those with a higher comorbidity index score, and those with more office visits were more likely to be up-to-date with lung cancer screening. Screened patients were more likely to not have commercial insurance. Black patients had lower odds of being screened than white patients. No clinician characteristics were associated with screening. Patients receiving care closer to the central health system and lung cancer screening clinic (i.e. urban practices) were more likely to be screened than patients in practices further away (suburban or rural practices). Patients receiving care from practices that were later adopters of the EHR were less likely to be screened. Patients from either rural or suburban practices were less likely to be screened than patients from urban practices.

Table 2.

Associations between being up-to-date with lung cancer screening and patient, clinician, and practice factors for Health System A.

| p-value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Patient age | 5-year difference | 0.03 | 1.09 | 1.01, 1.18 |

| Patient gender | Male versus female | 0.02 | 1.27 | 1.05, 1.55 |

| Comorbidity index | 1-unit difference | <0.01 | 1.24 | 1.20, 1.29 |

| No. of visits | 1-visit difference | <0.01 | 1.10 | 1.07, 1.13 |

| Race | Asian versus white | 0.07 | 0.48 | 0.06, 4.10 |

| Black versus white | 0.77 | 0.63, 0.94 | ||

| Other versus white | 0.80 | 0.36, 1.76 | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic versus non-Hispanic | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.39, 2.72 |

| Preferred language | Spanish versus English | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.04, 4.83 |

| Other versus English | 1.79 | 0.48, 6.67 | ||

| Insurance type | Medicaid versus commercial | <0.01 | 2.65 | 1.89, 3.71 |

| Medicare versus commercial | 1.62 | 1.24, 2.12 | ||

| Uninsured versus commercial | 1.72 | 1.22, 2.44 | ||

| Wellness visit during year | Yes versus no | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.81, 1.16 |

| Clinician characteristics | ||||

| Clinician age | <50 versus 50+ | 0.85 | 1.02 | 0.85, 1.21 |

| Clinician specialty | Internal versus family med. | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.50, 1.64 |

| OB/GYN versus family med. | 1.19 | 0.22, 6.35 | ||

| Year of graduation from residency | 5-year difference | 0.10 | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.09 |

| Ethnicity/race | Asian versus white | 0.27 | 1.02 | 0.82, 1.27 |

| Black versus white | 1.29 | 0.97, 1.73 | ||

| Hispanic versus white | 1.72 | 0.58, 5.06 | ||

| Attending versus residency | Attending versus resident | 0.39 | 1.19 | 0.80, 1.75 |

| Practice characteristics | ||||

| Practice location | Rural versus urban | <0.01 | 0.12 | 0.04, 0.37 |

| Suburban versus urban | 0.56 | 0.31, 0.99 | ||

| Practice size | 100-patient difference | 0.12 | 1.03 | 0.99, 1.07 |

| Year obtained EHRa | 1-year difference | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.48, 0.98 |

| Year obtained portal | 1-year difference | 0.13 | 0.72 | 0.46, 1.10 |

| Percent of patients using portal | 10% difference | 0.56 | 1.08 | 0.84, 1.38 |

| PCMH status (yes/no) | Yes versus no | 0.52 | 1.59 | 0.38, 6.63 |

| Patient insurance | Percent Medicaid (10% difference) | 0.20 | 1.40 | 0.84, 2.35 |

| Percent Medicare (10% difference) | 0.17 | 0.81 | 0.60, 1.10 | |

| Percent Private (10% difference) | 0.50 | 0.94 | 0.79, 1.12 | |

CI: confidence interval; EHR: electronic health record; OR: odds ratio; PCMH: patient centered medical home. Shaded rows indicate p < 0.05.

Odds ratio for year obtained EHR reflects one year later compared to one year earlier.

Discussion

There was evidence that several patient and practice factors were associated with screening uptake, though there was no evidence of association for clinician factors. Patients with more frequent visits, a surrogate for more opportunities to be offered screening, were more likely to be screened. The finding that patients with more comorbidities were more likely to be screened is consistent with previous research.22 Although a one-unit difference in comorbidity score would not necessarily disqualify a patient from lung cancer screening, this finding is also concerning because patients who are sicker may experience more complications from lung cancer treatment.22 This result might be capturing the phenomenon documented by Richards et al.16 that more people are inappropriately screened than appropriately screened. Alternatively, a higher comorbidity index may be a surrogate for a greater number of pack-years of smoking and meeting the 30 pack-year inclusion criterion to be screened. The lower screening rates in rural and suburban practices could be related to the distance from screening facilities.

Despite caring for more underserved and minority patients in an urban setting, health system A had substantially greater rates of lung cancer screening. This health system has a lung cancer screening clinic, offered free screenings in 2012–2013 (the year before and of the guideline change), and hired a full-time program coordinator in 2015 (two years after the change) to further promote screening. The other health systems relied on practices and clinicians to implement the new guideline, the more traditional approach to guideline implementation. Health system A’s approach may explain both the high baseline screening rate (10%) compared to the national rate (4%) and the large increase over time, which has also not been seen nationally.6 This conclusion is supported by the correlation between practice proximity to the lung cancer clinic and the likelihood of being screened. While the finding that patients without commercial insurance were more likely to be up-to-date is surprising, this may be explained in part by the free screenings offered at the beginning of the study period and the introduction of CMS coverage at the end of the study period. It is also possible that this health system approach helped increase overall lung cancer screening uptake and even selectively helped underinsured patients.

Limitations

This study uses age and current smoking status as a proxy for screening eligibility rather than the full USPSTF criteria. While this will result in lower screening rates (i.e. many current smokers will not have a 30 pack-year history of smoking and should not be screened), trends over time should remain valid. Additionally, screening that happened outside of the health system would likely not be included in the EHR data and would be missed. As a repeated cross-sectional cohort study, some patients were not included in the sample for all four years. Finally, the provision of free screenings by health system A may limit generalizability. With the Affordable Care Act, however, services recommended by the USPSTF are covered without copays and so would essentially be free.8

Conclusions

Lung cancer screening using CT remains exceptionally low compared to other cancer screenings. More frequent access to healthcare might play a role, providing more opportunities for eligible patients to be recommended for screening. Future work should study the impact of a health system level approach on increasing screening rates.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Virginia Ambulatory Care Outcomes Research Network and OCHIN for their support. We additionally thank Paulette Kashiri, Nate Warren, Erik Geissal, Steve Rothemich, and Pat Tam for their assistance with data collection.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R03 HS25032-01), National Cancer Institute (R01 CA168795-01), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR002649). Analytic support was provided by the VCU Massey Cancer Center Biostatistical Shared Resource, supported, in part, with funding from NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30-CA016059.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Krist is currently the Vice Chair for the USPSTF. This manuscript does not necessarily represent the views and policies of the USPSTF.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer VA and USPST Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160: 330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Preventive Services Task Force. Final update summary: lung cancer: screening, https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lung-cancerscreening (accessed 8 April 2019).

- 4.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma J, Ward EM, Smith R, et al. Annual number of lung cancer deaths potentially avertable by screening in the United States. Cancer 2013; 119: 1381–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A and Fedewa SA. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in the United States – 2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3: 1278–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N), https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274 (2015, accessed 12 April 2019).

- 8.Seiler N, Malcarney M- B, Horton K, et al. Coverage of clinical preventive services under the Affordable Care Act: from law to access. Public Health Rep 2014; 129: 526–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis JA, Petty WJ, Tooze JA, et al. Low-dose CT lung cancer screening practices and attitudes among primary care providers at an academic medical center. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015; 24: 664–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanodra NM, Pope C, Halbert CH, et al. Primary care provider and patient perspectives on lung cancer screening. A qualitative study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13: 1977–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dharod A, Bellinger C, Foley K, et al. The reach and feasibility of an interactive lung cancer screening decision aid delivered by patient portal. Appl Clin Inform 2019; 10: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphrey LL, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159: 411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Patel S, et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2018; 153: 954–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reich JM. Reservations regarding lung cancer screening guidelines. Chest 2018; 154: 715–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinsky PF, Bellinger CR and Miller DP Jr. False-positive screens and lung cancer risk in the National Lung Screening Trial: implications for shared decision-making. J Med Screen 2018; 25: 110–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards TB, Doria-Rose VP, Soman A, et al. Lung cancer screening inconsistent with U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. Am J Prev Med 2019; 56: 66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould MK, Sakoda LC, Ritzwoller DP, et al. Monitoring lung cancer screening use and outcomes at four cancer research network sites. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017; 14: 1827–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huo J, Shen C, Volk RJ, et al. Use of CT and chest radiography for lung cancer screening before and after publication of screening guidelines: intended and unintended uptake. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177: 439–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krist AH, Aycock RA, Etz RS, et al. MyPreventiveCare: implementation and dissemination of an interactive preventive health record in three practice-based research networks serving disadvantaged patients – a randomized cluster trial. Implement Sci 2014; 9: 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org/ (2018, accessed 23 April 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wickham H ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zahnd WE and Eberth JM. Lung cancer screening utilization: a behavioral risk factor surveillance system analysis. Am J Prev Med 2019; 57: 250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]