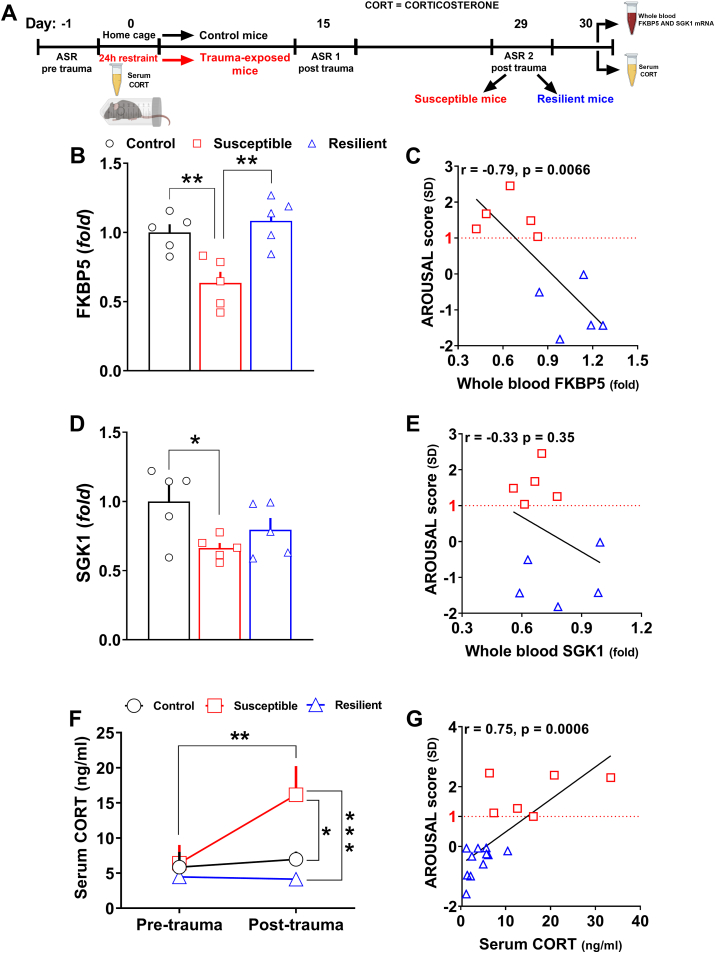

Fig. 5.

Divergent peripheral transcriptional signatures driven by selected PTSD candidate genes as well as marks of HPA axis dysfunction further validated the segregation in susceptible and resilient subpopulations.(A) Timeline: the day after the segregation, control (n = 5), susceptible (n = 5) and resilient mice (n = 5) from one cohort were sacrificed to collect whole blood. Abundance of transcripts was assessed by qPCR. In other control (n = 7), susceptible (n = 6) and resilient mice (n = 11) from an independent cohort, serum was isolated from blood collected both 5–6 h before the trauma and the day after the identification in subpopulations. (B) FKBP5 mRNA expression (Stresssusceptibility, F(2, 12) = 10.82, P = 0.0021) in the whole blood. (C) Linear correlation between the arousal score and the expression of FKBP5 in the whole blood (r = −0.79, P = 0.0066). (D) SGK1 mRNA expression (Stresssusceptibility, F(2, 12) = 3.945, P = 0.048) in the whole blood. (E) Linear correlation between the arousal score and the expression of SGK1 in the whole blood. (F)Pre-trauma and post-trauma serum corticosterone levels (Stress susceptibility, F(2, 21) = 4.984, P = 0.0169;TimeF(1, 21) = 7.306, P = 0.0133;Stress susceptibilityxTimeF(2, 21) = 5.474, P = 0.0122). (G) Linear correlation between the arousal score and post-trauma serum corticosterone level ( r = 0.75, P = 0.0006). Fold changes are expressed relative to transcript levels of control mice. Two-way RM ANOVA or one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Values are expressed as means ± s. e.m.