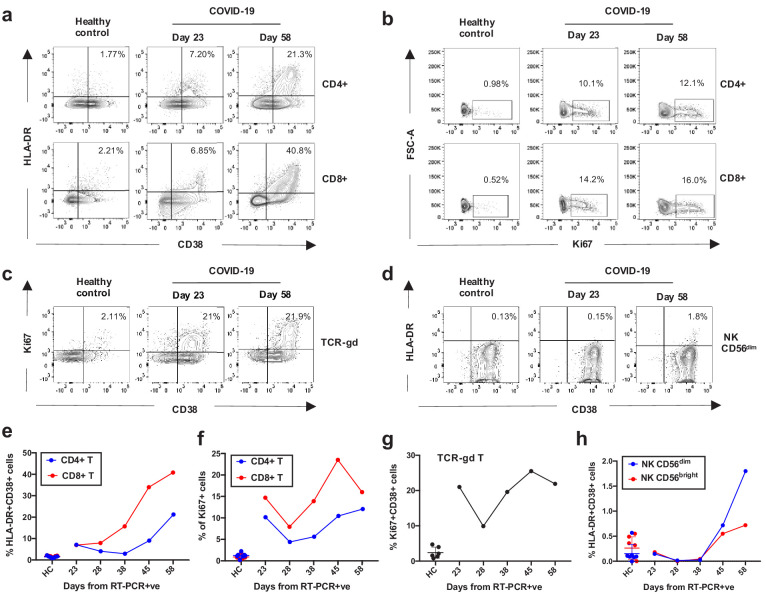

Figure 3. Kinetics of the adaptive and innate immune response in a COVID-19 patient during ICU treatment.

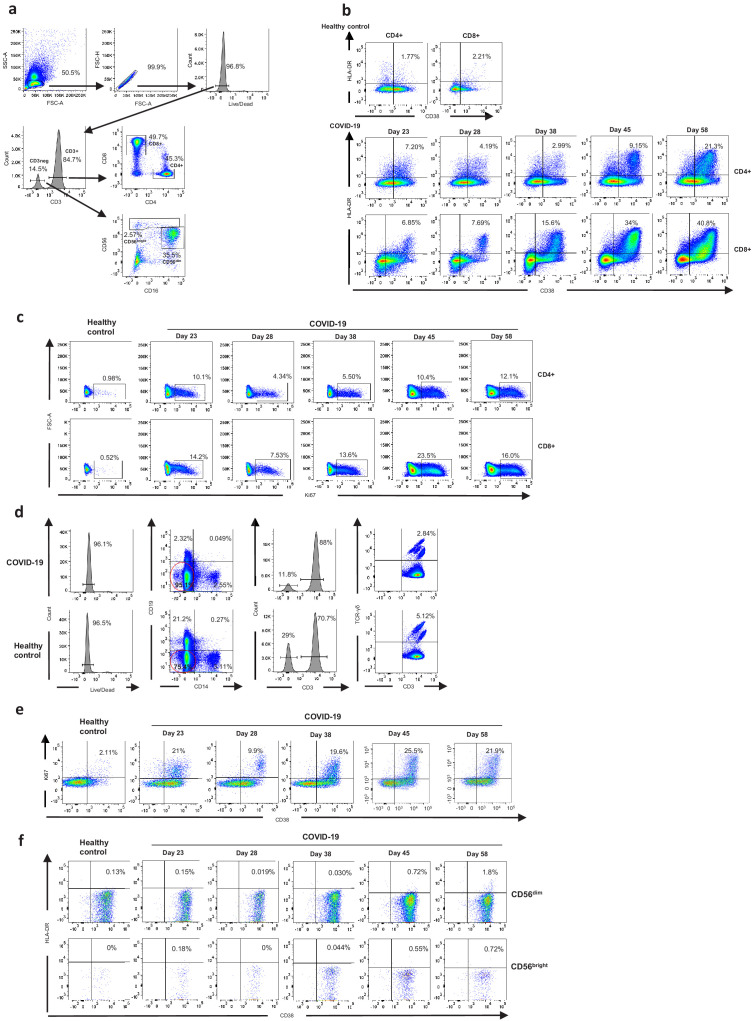

(a–d) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the expression of activation and proliferation markers on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (top and bottom panels, respectively in a, b), TCR-γδ T cells (c) and NK cells (d: plots shown for NK CD56dim cells) in a healthy control and the COVID-19 patient (at days 23 and 58). (e-f) Immune activation and proliferation levels are summarized for healthy controls (HC, n = 7) and five longitudinal time points of the COVID-19 patient and are assessed as co-expression of HLA-DR and CD38 (e) and expression of Ki67 (f) in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, co-expression of CD38 and Ki67 by TCR-γδ T cells (g), and co-expression of HLA-DR and CD38 in NK CD56dim cells (h). Gating strategies for each population are included in Figure 3—figure supplement 1. All data is obtained by flow cytometry and samples were acquired on a Becton Dickinson LSR Fortessa X-20.