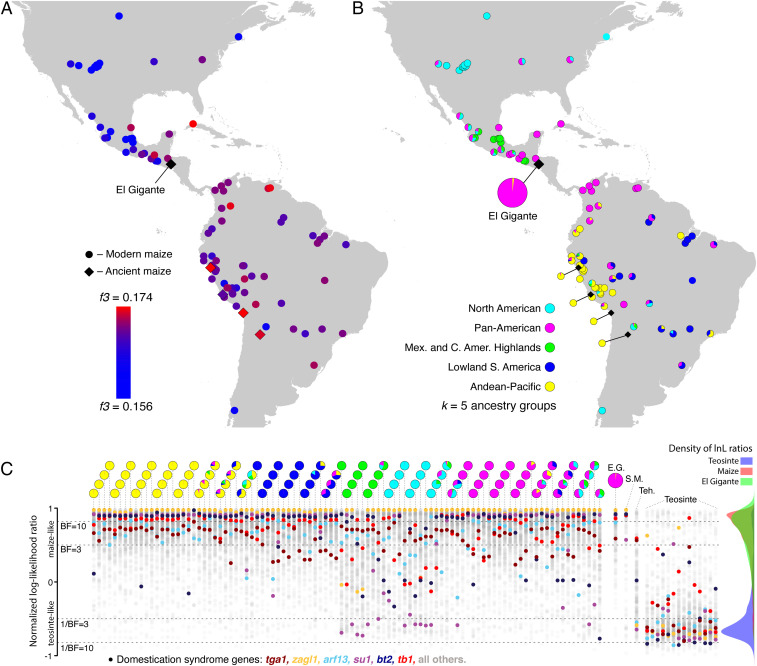

Fig. 2.

Genetic affinities and domestication status of archaeological El Gigante maize. (A) Outgroup-f3 statistics in the form f3(Tripsacum; X, El Gigante) with all other maize samples in position X, showing that maize samples sharing the most drift with El Gigante maize are modern and ancient genomes from South America. The sample in Cuba with a high f3 value is from a HapMap2 landrace with known origins in Argentina. (B) Ancestry proportions of modern and ancient maize estimated via model-based clustering. (C) Estimation of domestication status in El Gigante and other maize via AIMs located near and within domestication syndrome genes. The y axis displays normalized log-likelihood of a gene being drawn from a maizelike (1) vs. teosintelike (−1) reference panel, with significance thresholds marked where Bayes factors (BF) (and 1/BF) ≥3 and ≥10. Each column of dots shows a single genome with up to 278 individual gene lnL ratios, with ancestry proportions corresponding to B above each column. In El Gigante maize (E.G.), domestication genes overlap the modern maize reference panel and deviate strongly from the teosinte panel, and all six specifically analyzed domestication genes are maizelike with at least BF > 3. In contrast, Middle Holocene Tehuacán Valley maize (Teh.) carries a mixture of maizelike and teosintelike variants as previously reported (23). Mid-Holocene San Marcos maize (S.M.) was also previously shown to be a partial domesticate (24), although more maizelike than the Tehuacán specimen (26), a finding reinforced here.