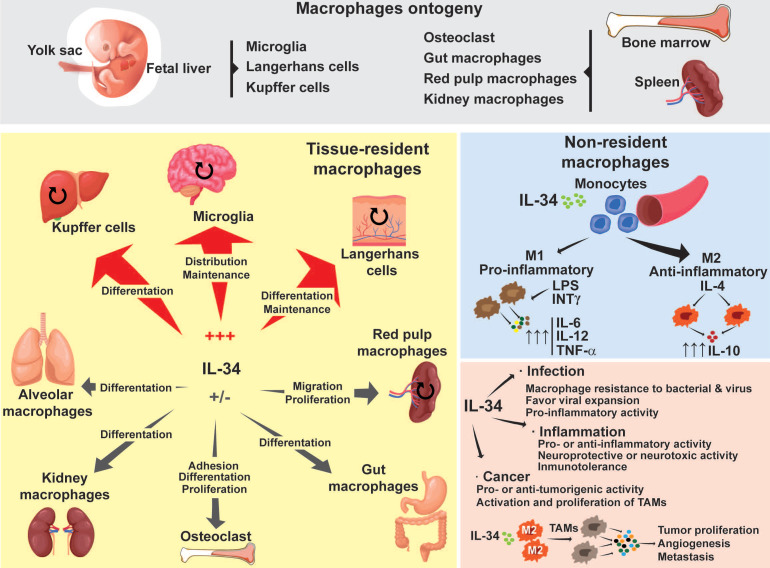

Figure 1.

Macrophage ontogeny and the implications of IL-34 during macrophage differentiation. Depending on their origin, macrophages are divided into two different populations: tissue-resident macrophages and non-resident macrophages. Tissue-resident macrophages originate in the embryonic yolk sac, fetal liver, and bone marrow. Tissue-resident macrophages are capable of self-renewal of their own population (round arrows). However, in pathogenic situations, non-resident macrophages can migrate into the affected tissues and replenish the local populations by acquiring tissue specificities. Depending on the tissue, IL-34 drives macrophage differentiation, proliferation, maintenance, migration, and adhesion. Non-resident macrophages originate in the bone marrow and spleen. Circulating monocytes can extravasate and migrate to different tissues where, through the actions of different growth factors, they induce their polarization into M1 or M2 subtypes. M1 macrophages detect pathogenic particles or inflammatory molecules such as LPS or INT-γ and display pro-inflammatory functions by secreting pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-6 and Il-12. M2 macrophages are sensitive to molecules such as IL-4 or IL-13 and display an anti-inflammatory profile by producing soluble factors such as IL-10. IL-34 mainly induces the polarization of monocytes into an M2 subset. In pathological situations such as bacterial or viral infection, or inflammation, IL-34 can act as a pro- or anti-viral/inflammatory agent. In cancer, IL-34 behaves in a pro- or anti-tumor manner. IL-34 also induces macrophage differentiation into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which are characterized by an M2 phenotype that promotes tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis. The capacity of IL-34 to act in a positive or negative direction is tissue- and microenvironment-dependent.