Abstract

Background:

Variation describing pharmacists’ patient care services exist, and this variation contributes to the prevalent misunderstanding of the roles of pharmacists. In contrast, standard phraseology is a critical practice among highly reliable organizations and a way to reduce variation and confusion.

Objective:

This work aims to identify and define pharmacists’ patient care service terms to identify redundancies and opportunities for standardization.

Methods:

Between May to August 2018, terms and definitions were searched via PubMed, Google Scholar and statements/policies of professional pharmacy organizations. Two references per term were sought to provide an “early definition” and a “contemporary definition.” Only literature published in English was included, and data gathered from each citation included the date published, the term’s definition, and characterization of the reference as either a regulatory or professional body. A five-person expert panel used an iterative technique to verify and revise the list of terms and literature review results. Terms were then searched in the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Heading Database (MeSH) in July of 2019.

Results:

There are fifteen commonly misunderstood terms that refer to the patient care services offered by pharmacists. The appearance of terms spanned nearly five decades. Nearly half of terms first appeared in regulatory, law or policy documents, and of these, two terms had contemporary definitions appearing in the professional literature that differed from their early regulatory definition. Three opportunities to improve standardization include: (1) The development and curation of standardized phraseology systems similar to nursing’s Clinical Care Classification System; (2) Academics’ adherence tostandardized MeSH terms; and (3) Clarification of pharmacy education accreditation standards.

Conclusion:

Numerous terms are used to describe pharmacists’ patient care services, with many terms’ definition overlapping in several key components. The profession has made concerted efforts to consolidate and standardize terminology in the past, but more opportunities exist.

Keywords: Pharmaceutical Services, Medication Therapy Management, Standardized Nursing Terminology, Health Communication, Interdisciplinary Communication, Phrase

INTRODUCTION

Professional consensus on terminology is essential to patient care, scientific advancements, and professional progress, because without standardization, concepts remain ill-defined and scientific findings become variable. Terminology in particular often lags behind a rapidly advancing scientific field, such as modern day pharmacy. For example, pharmacists’ dispensing role dates back to the 15th century. However, over the last few decades, pharmacists’ role in healthcare has expanded to that of a patient care provider1,2The first reference in modern US literature to pharmacists’ role in patient care appeared in the 1960’s via the term Clinical Pharmacy.3 Today, however, the scope of services within the pharmacy profession is just as broad and diverse as the patient populations, settings, and care teams that pharmacists serve.2,4,5As pharmacists’ roles rapidly changed,professionals, regulators and lay-persons alike attempted to maintain pace, and an explosion of terminology appeared. This terminology boom has caused confusion and misunderstanding among pharmacists, but also among other healthcare providers, patients, payers, and policymakers, alike.

There are several (likely non-mutually exclusive) reasons why pharmacist services terminology lacks uniformity. First, pharmacist services’ terminology likely lacks standardization and general recognition due to historical contexts. To explain, many modern healthcare terms can be traced back to an ancient root word with a physical meaning. For instance, “appendix” comes from the Latin “appendō” (“hang upon”) and the suffix “-ectomy” is rooted in Greek ektomḗ (“excision”); putting the two together formsthe term “appendectomy.” Second,a word to mean “cognitive services related to the counseling of a modern medication”was never generated via natural etymology. Alternatively, many different stakeholders began to invent terms for roles being provided; states wrote laws, professional organizations developed positions, and researchers published studies, all developing and referring to terms independently and simultaneously. Third, another cause for ambiguity and confusion now exist most likely due to the lack of one, unified voice for the pharmacy profession, as several independent institutions created terms in a short period of time. Fourth, as pharmacists’ roles have significantly expanded from dispenser, there has been a lack of formal processes within the profession to ensure terms’standardization. For example, ideally, all pharmacy stakeholders would agree that any use of a term would comply with how the term was defined by consensus from various national pharmacy organizations. Fifth, pharmacist roles are frequently shifting due to marketplace demands and needs. Such changes make attempts to characterize services a moving target and difficult. Sixth, the description of pharmacists’ patient care servicesis potentially difficult for several reasons. First, the services are cognitive as opposed to physical (with the exception of some physical examinations like taking a blood pressure, or administering immunizations). In other words, pharmacists’ patient care services are completed via review, decision-making, and verbal/written actions; and the fact that these services have neither physical output nor are diagnostic likely contribute to their ambiguity. Lastly, pharmacists’ patient care services are potentially difficult to define because, to date, there is no consistent way to measure the outcome of these services. Many other reasons for variation can be pointed to including various terminology within Doctor of Pharmacy curricula, the numerous and distinct settings in which pharmacists practice, the evolution and drift of a term’s meaning over time, and discrepancies between terms’ meaning in the professional and in society in general, among others.

Despite the reasoning why pharmacy lacks service term standardization, the profession has poignantly felt the consequences. The variable terminology potentiates pharmacists’ challenges to care settings and team integration, as policy makers, decision makers, and healthcare team members alike misunderstand pharmacists’ skills, roles and value.6 This phenomena spills into payment arenas, thus blocking pharmacists from reimbursement for patient care services, a feature that is critical to any sustainable business model.7 Even more concerning is that inconsistent use of terminology describing pharmacists’ services in the primary literature has made it difficult to rigorously evaluate outcomes via systematic reviews or meta-analysis.8 As such, a lack of standardized terminology among pharmacist provided patient care service terminology has resulted in contradictory health services research.8,9 Effectively, without definitive standardization, pharmacists’ patient care services cannot be accurately assessed from study to study, and large meta-analyses are difficult to perform. The lack of consensus and standardization in pharmacy practice ultimately undermines generalizability of pharmacy practice research. This likely contributes to diminished perceptions of pharmacists’ value to patient care teams, further potentiates misunderstanding, and ultimately completes a self-fulfilling cycle.

Broadly, the pharmacy profession has yet to achieve a consensus-based standardized terminology for patient care services provided by pharmacists. This is arguably the most critical step toward maximizing pharmacists’ potential as valued members of interdisciplinary healthcare teams. A helpful first step toward developing consensus definitions could be to trace the fluidity, duplication, and misuse of commonpharmacy-specific patient care terms. Therefore, the objective of this work was to identify, define, and spotlight the most commonly recognized patient care service terms in pharmacy to identify redundancies and opportunities for standardization. This research brought together practicing pharmacists and pharmacy researchers from across the U.S. to evaluate commonly used terms in pharmacy practice with the goal of reigniting and stimulate a national discussion.

METHODS

This study is a literature review with results validated via consensus from an expert panel.

Term Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Terms were included in this review if: (1) it referred to a service that a pharmacist provides to a patient and (2) the authors of this study believed the term was commonly misunderstood by any stakeholder, including pharmacists or other healthcare professionals, payers, government, regulatory entities and patients. Terms that appeared as verbs to complete nouns (e.g. “process”) were considered synonymous with the service noun. If terms were considered synonymous, the authors used their experience with pharmacy practice literature to determine the more commonly used term. The more commonly used term was used for the literature search, and the less used synonym was presented alongside the found definition. Terms were excluded if they: (1) lacked a direct patient care activity (e.g. population health) or (2) were commonly understood by any stakeholder above (e.g. prescription filling, immunization).

Search Strategy and Data Collection

First, an a-priori list of pharmacy practice service terms was developed by three authors (SG, CU, JB). From May to August 2018, each term was searched via PubMed, Google Scholar and professional pharmacy organizations’ (e.g. APhA, ACCP, ASHP, JCPP) white papers, position statements and policies. Each term was searched with the words “pharmacist” and “pharmacy,” as several terms referred to services not exclusively provided by pharmacists. Citations within each found reference were also searched to determine their inclusion/exclusion. Becausethe meaningof words changes over time, two references were sought for each term to provide an ‘early definition’ and a ‘contemporary definition’. Data gathered from each reference included the term’s definition, citation with year published, and categorization of the reference as either a ‘regulatory’or ‘professional’ or ‘regulatory’reference. References fell into the regulatory category if they were generated from government, accreditingbodies or regulating organizations (e.g. laws, certifications, standards). Conversely, references were considered ‘professional’ if they generated from non-regulatory sources, such as academic journals and professional organizations. These steps were reiterated after expert panel members’ review.

Citation Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Only literature published in English was included. A reference was included as the ‘early definition’ of a term if it was: (1) the earliest appearance of the term in reference to pharmacy-practice, and/or (2) the earliest appearance proclaimed authority on the term’s definition and/or (3) the earliest appearance from a regulatory or government-affiliated reference that defined the term without regard to any specific healthcare professional whatsoever (e.g. a federal health safety agency describing “medication reconciliation” without indication of what healthcare professional(s) provided the service). A reference was included as the ‘contemporary definition’ of a term if it was the most current reference matching the criteriaabove and/or specifically noted a revision of the term’s definition or meaning.

References that denoted terms in ways other than in the context of pharmacy were excluded. For example, if in searching the term “medication management,” a reference pertained to health information technology via “medication management system,” that reference was excluded, as it contained no description of a pharmacist provided service. Further, references that contained the service term but used the term todenote services provided by anyone other than a pharmacist were excluded (e.g. a research article describing “medication reconciliation” completed by a nurse).Lastly, if a reference contained a term that lacked sufficient description to conclude that term’s definition, it was excluded.

Expert Panel Review and Data Revisions

A five-person expert panel used an iterative technique to verify results’completeness and validity. Individuals on this panel (NR, MC, SF, SH, MS) were purposefully selected for theirnational recognition, professional reputation and experience in pharmacy practice. Four were licensed pharmacists with expertise in community and primary care settings, and another four (not mutually exclusive) were tenured academics who conduct health-services research. In total, the panelrepresented over 110 yearsof pharmacy practice experience.

Four of the five expertpanel members (NR, MC, SF, SH) independently reviewed the findings from the first round of literature search in Qualtrics® software. Specifically, reviewers were asked toagree or disagree if they felt: (1) each reference appropriately matched the inclusion criteria; (2) if any service termswere missing from the review; and (3) if any service terms that appeared in the results did not belong. To access references, expert panel members were instructed to ask: “was the presented reference the profession’s recognized reference of the term’s definition, or did a more professionally-recognized reference exist?”To identify missing terms or access inappropriateness of included terms, expert panel members were instructed to ask themselves: “is this term related to pharmacist services and commonly misunderstood by pharmacists or other healthcare professionals, payers, government, regulatory entities and patients?”Three researchers (SG, CU, and JB) then reviewed the expert panel’s answers, and revised the data with a second round of literature review via the same search methods above. The revised data was then returnedback to the four expert panel members for a second round of independent review and agreement. As a blind double-check, the fifth expert panel member (MS) neither participated in the data’s first or second review, and rather provided a third independent review of final results for clarity, completeness and agreement. Once complete, all terms were searched in the National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) online Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) Database in July of 2019.

RESULTS

There are 15 pharmacist-provided service terms that are potentially misunderstood by pharmacists, payers and other healthcare providers alike (Table 1).Originally, fifteen serviceterms were included in the original list developed a-priori for the first round of literature review. Thirteen of these original 15 terms were retained, and two were excluded after the first round of expert panel review; specifically, the terms Collaborative Practice Agreement and Disease State Management were excluded. The expert panel justified exclusion of Collaborative Practice Agreement, stating the term does not refer to a service, but rather a regulatory agreement (i.e., a document) between a pharmacist and a physician. As such, pharmacist services are facilitated by Collaborative Practice Agreements, but the agreements themselves do not represent any services rendered. Similarly, the panel excluded the term Disease State Management, citing that this term was likely well understood by pharmacists, payers, and other stakeholders alike. Also during this first round of review, the expert panel identified three pharmacist patient care services terms that met inclusion criteria but were missing from the first round of literature search, specifically Transitions of Care,Pharmacogenetics/genomics, and Polypharmacy. However, the panel ultimately decided to exclude Polypharmacy from inclusion citing that it was not a service but rather a qualitative description of a patient’s medication state.

Table 1:

Pharmacists’ Patient Care Service Term’s Early and Contemporary Definitions

| Term | Early Definition | Contemporary Definition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Reference Type | Definition | Reference | Year | Reference Type | Definition | Reference | |

| Clinical Pharmacy | 1969 | Professional | A concept or philosophy emphasizing the safe and appropriate use of drugs in patients. | Francke GN. Evolvement of clinical pharmacy.31 | 2008 | Professional | The area of pharmacy concerned with the science and practice of rational medication use. | American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy.32 |

| Pharmaceutical Care | 1990 | Professional | The responsible provision of drug therapy for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes that improve a patient’s quality of life. | Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care5 | 2018 | Professional | A patient-centered, outcomes oriented pharmacy practice that requires the pharmacist to work in concert with the patient and the patient’s other healthcare providers to promote health, to prevent disease, and to assess, monitor, initiate, and modify medication use to assure that drug therapy regimens are safe and effective. | American Pharmacist Association. Principles of practice for pharmaceutical care.33 |

| Patient Counseling | 1990 | Regulatory | A mandated service that at minimum includes counseling of: drug name, use and expected action, administration, side-effects, self-monitoring, storage, interactions, refill information, and actions taken in the event of a missed dose. | The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990.10 | 1997 | Professional | A responsibility of the pharmacy profession for providing patient education and counseling in the context of pharmaceutical care to improve patient adherence and reduce medication-related problems. | American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists. Guidelines on pharmacist-conducted patient education and counseling.11 |

| Drug Utilization Review (aka, Prospective Drug Review) | 1991 | Regulatory | A review of patients’ prescription and medication data before, during and after dispensing to assure that prescriptions (i) are appropriate, (ii) are medically necessary, and (iii) are not likely to result in adverse outcomes; DUR was originally required by CMS for each State’s Medicaid program. | USSocial Security Act. In. Title XIX. Grants to States for Medical Assistance Programs.34 | 2009 | Professional | An authorized, structured, ongoing review of prescribing, dispensing and use of medication….[that] involves a comprehensive review of patients’ prescription and medication data before, during and after dispensing to ensure appropriate medication decision-making and positive patient outcomes. | Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. Drug utilization review. 35 |

| Pharmacogeno mics/genetics* | 1992 | Professional | To appreciate the clinical significance of polymorphic drug metabolism and provide a basis for the application of this knowledge to a variety of practice settings. | Straka RJ, Marshall PS. The clinical significance of the pharmacogenetics of cardiovascular medications.36 | 2011 | Professional | The use of genetic information to predict an individual’s response to a drug. | Reiss SM. Integrating pharmacogenomics into pharmacy practice via medication therapy management.37 |

| Medication Management | 1993 | Professional | Pharmacist interventions designed to assist people in managing their medication regimens. | Tett SE, Higgins GM, Armour CL. Impact of pharmacist interventions on medication management by the elderly: a review of the literature.38 | 2018 | Professional | A spectrum of patient-centered, pharmacist provided, collaborative services that focus on medication appropriateness, effectiveness, safety, and adherence with the goal of improving health outcomes. This encompass a variety of terms, such as Medication Therapy Management (MTM), Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM), Collaborative Medication Management, etc. |

Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Medication management services (MMS) definition and key points.39 |

| Collaborative Drug Therapy Management | 1995 | Professional | Legislative and regulatory provisions that allow for prescribing and related activities by the pharmacist as a component of pharmaceutical care. | Zellmer WA. Collaborative drug therapy management.20 | 2012 | Professional | A formal partnership between a pharmacist and physician or group of pharmacists and physicians to allow the pharmacist(s) to manage a patient’s drug therapy. | Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. Practice advisory on collaborative drug therapy management.40 |

| Transitions of Care (aka, Care Transitions, Care Continuum) | 1996 | Professional | To develop a clinical pathway indicating a predictable course of care. | Goldenberg RI, Bell SH, Wright J, et al. HIV continuum of care: challenges in management.41 | 2012 | Regulatory | The movement of patients between health care practitioners, settings, and home as their condition and care needs change. | The Joint Commission. Transitions of care: the need for a more effective approach to continuing patient care.42 |

| Medication Therapy Management | 2003 | Regulatory | A program…with respect to targeted beneficiaries…to improve medication use, reduce the risk of adverse events, and improve medication adherence. | H.R.1; Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. (Public Law 108–173).43 | 2008 | Professional | Services that are dependent on pharmacists working collaboratively with physicians and other healthcare professionals to optimize medication use in accordance with evidence-based guidelines and include medication therapy review (MTR), a personal medication record (PMR), a medication-related action plan (MAP), intervention and referral, and documentation and follow-up. | Medication therapy management in pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service model (version 2.0).44 |

| Medication Reconciliation | 2006 | Regulatory | The process of comparing a patient’s medication orders to all of the medications that the patient has been taking…to avoid medication errors such as omissions, duplications, dosing errors, or drug interactions. | The Joint Commission. Sentinel event alert.45 | 2010 | Regulatory | The process of identifying the most accurate list of all medications that the patient is taking, including name, dosage, frequency, and route, by comparing the medical record to an external list of medications obtained from a patient, hospital, or other provider. | US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. EHR Incentive program. Eligible professional meaningful use menu set measures. measure 7 of 10; stage 1.46 |

| Comprehensive Medication Review | 2010 | Regulatory | An annual, real-time, interactive, person-to-person, or telehealth consultation performed for a patient or caregiver by a pharmacist or other qualified provider that includes: collecting patient-specific information, assessing medications to identify medication-related problems, developing a prioritized list of medication-related problems, and creating a plan to resolve them, and has a written summary in the Center for Medicare and Medicaid’s standardized format. | US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CY 2018 medication therapy management program guidance and submission instructions.47 | 2017 | Professional | The pharmacist looking at the patient as a whole by reviewing the patient’s medication list, medication allergies, immunization status, and any other clinical need for the patient | Pagano GM, Groves BK, Kuhn CH, Porter K, Mehta BH. A structured patient identification model for medication therapy management services in a community pharmacy.48 |

| Targeted Medication Review | 2010 | Regulatory | A service Medicare Part D sponsors are required provide to all beneficiaries enrolled in the sponsor’s MTM program that includes quarterly medication reviews and follow-up interventions as necessary. | US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CY 2018 medication therapy management program guidance and submission instructions.47 | 2017 | Professional | When the pharmacist focuses on one area of the patient’s health care, for example, when a pharmacist counsels a patient with diabetes on the importance of being on statin therapy and then contacts their doctor to initiate a targeted medication review for them. | Pagano GM, Groves BK, Kuhn CH, Porter K, Mehta BH. A structured patient identification model for medication therapy management services in a community pharmacy.48 |

| Compressive Medication Management | 2012 | Professional | A standard of care that ensures each patient’s medications are individually assessed to determine that each medication is appropriate, effective, safe, and able to be taken by the patient as intended….[that] includes an individualized care plan that achieves the intended goals of therapy with appropriate follow-up to determine actual patient outcomes. This all occurs because the patient understands, agrees with, and actively participates in the treatment regimen, thus optimizing each patient’s medication experience and clinical outcomes. | Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. The patient centered medical home: integrating comprehensive medication management to optimize patient outcomes resource guide.49 | 2016 | Professional | The standard of care that ensures each patient’s medications (i.e., prescription, nonprescription, alternative, traditional, vitamins, or nutritional supplements) are individually assessed to determine that each medication is appropriate for the patient, effective for the medical condition, safe given the comorbidities and other medications being taken, and able to be taken by the patient as intended. | American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Comprehensive medication management in team-based care.50 |

| Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process | 2014 | Professional | A patient-centered approach in collaboration with other providers to optimize patient health and medication outcomes that includes: Collection of the necessary information; Assessment of the information collected to identify and prioritize problems; Development of an individualized patient-centered care plan; Implementation of the care plan; and Follow-up to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the care plan. | Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. The pharmacists’ patient care process.17 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Chronic Care Management | 2016 | Regulatory | A service under the United States’ Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Medicare Physician Fee Schedule consisting of at least 20 min clinical staff time directed by MD or other qualified healthcare professional per month furnished to Medicare patients meeting multiple chronic condition criteria. | United States Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Learning Network. Chronic care management services.51 | 2018 | Professional | A fee-for-service program intended to encourage ambulatory care practices to utilize value-based care delivery and to compensate for coordinated healthcare provided outside of a patient visit. | Fixen DR, Linnebur SA, Parnes BL, Vejar MV, Vande Griend JP. Development and economic evaluation of a pharmacist-provided chronic care management service in an ambulatory care geriatrics clinic.52 |

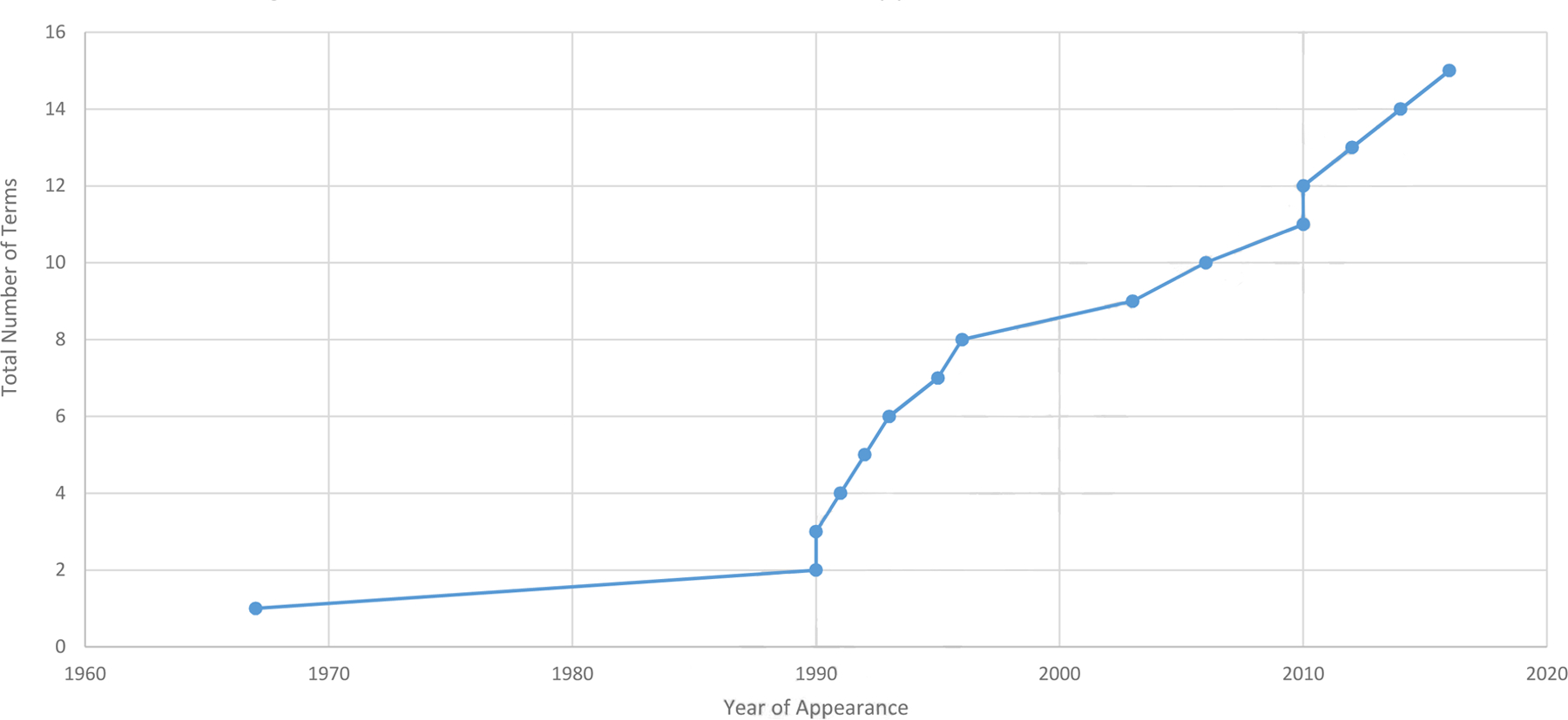

After the second round of literature and expert panel review with the revised data two, the final results included fifteen terms. These fifteen terms appeared in the literature over five decades, with the earliest term Clinical Pharmacy’s appearance in 1969, and the most recent term, Chronic Care Management’s appearance in 2016 (Fig 1). Of these final fifteen, seven (46.7%) terms’ early definitions came from a regulatory reference and eight (57.1%) from a professional reference; alternatively, 80% of terms’ contemporary definitions were found within professional references. No contemporary definition was found for the term Pharmacist Patient Care Process, as all definitions in the literature did not vary from the originally published definition.

Fig 1:

Pharmacists’ Patient Care Service Term’s Appearance in Literature Over Time

Drift Between Terms’ Regulatory and Professional Definitions

Differences were found between multiple terms’ regulatory definitions and professional definitions. Specifically, among the seven terms that appeared first in regulatory, law or policy references, six had a contemporary definition found from a professional reference. Of these six, four terms’ contemporary professional definition differed little from the early regulatory definition (Comprehensive Medication Review, Targeted Medication Review, Chronic Care Management, and Drug Utilization Review).However, the remaining to two terms, Patient Counseling and Medication Therapy Management, had contemporary definitions found in the professional literature that differed moderately from the early definition found in the regulatory reference.

Originally appearing under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, Patient Counseling was originally defined to include only counseling of “drug name, use and expected action, administration, side-effects, self-monitoring, storage, interactions, refill information, and actions taken in the event of a missed dose.”10 However, Patient Counseling’s contemporary definition was expanded to include “care to improve patient adherence and reduce medication-related problems.”11 The difference between Patient Counseling’s early and contemporary definitions was nuanced, but distinct, nonetheless. Whereas Patient Counseling’s early definition only concerned warnings regarding side effects and actions on account of a single missed dose, the contemporary definition expanded pharmacists’ responsibility to counsel on avoidance and amelioration of all medication-related problems (not just side-effects alone), and non-adherence to the entire course of therapy (as opposed to a single missed dose).

The other discrepancy between an early regulatory definition and a contemporary professional definition regarded the term Medication Therapy Management. First defined in 2003 via the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, Medication Therapy Management referenced service for Medicare Part D beneficiaries, only. The contemporary professional definition differed from the early regulatory definition in thatMedication Therapy Management services were described regardless of insurer or payer (i.e. a service not just Medicare Part D beneficiaries) suggesting services could be delivered to any patient.

Drift Between Terms’ Early and Contemporary Definitions in the Professional Literature

Seven of the fifteen terms included in this review were only found within the professional literature, including Clinical Pharmacy, Comprehensive Medication Management, Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process, Pharmaceutical Care, Collaborative Drug Therapy Management, Medication Management Services, and Pharmacogenomics. Of these, only one term had minimal drift. Specifically, Medication Management Services’s early 1993 definition was updated in 2018 by the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practice (JCPP). In this revision, JCPP specified Medication Management Services’ focus, goals and role as an umbrella term in relation to other service terms.

Medical Subject Heading Findings

Only five of the fifteen terms included in this review appeared as MeSH terms including Medication Therapy Management, Medication Reconciliation, Pharmacogenetics, Drug Utilization Review, and Counseling. The term Pharmaceutical Care appeared in the scope of Mesh term Clinical Pharmacists as “pharmacists with clinical training to provide patient centered, evidence-based pharmaceutical care…” but was not a separate MeSH term itself. The MeSH term Pharmaceutical Services [N02.421.668] did not reflect patient care services as branches primarily focused on products (e.g. Prescriptions) or location (e.g., Community Pharmacy Services; Pharmaceutical Services, Online; and Pharmacy Service, Hospital) Similarly, Pharmacy Services, Hospital described only “the receiving, storing, and distribution of pharmaceutical supplies,” without regards to patient-services. Terminology found in this review neither appeared readily in the MeSH header Pharmacists [M01.526.485.780], as Community Pharmacists and Retail Pharmacistswere separate MeSH concepts under the Pharmacists heading and contained no scope descriptions whatsoever.

Overlap Among All Definitions

Overall, all terms’ definitions, regardless if they were an early or contemporary definition, were an allusion or description of pharmacists using their clinical knowledge to make a professional judgement to affect a patient’s medication-related outcome. Nearly half of terms’ definitions specifically cited collaboration or other coordination with physicians, prescribers and/or other healthcare professionals (Pharmaceutical Care, Medication Management Services, Collaborative Drug Therapy Management, Medication Therapy Management, Targeted Medication Review, and Chronic Care Management). Several terms’ definitionsspecifically mention optimizing patients’ ability to self-manage and/or adhere to medications, including Medication Management Services, Patient Counseling, and Comprehensive Medication Management.

DISCUSSION

Terms describing pharmacist services are numerous, with a spike of terms appearing in the literature after 1990. However, many terms’ meaning overlap and in some cases are indistinguishable from one another. In essence, all terms’ definitions allude to pharmacists using their clinical judgement to make a decision that will ultimately affect a patient’s medication-related outcome. Therefore, there is a considerable opportunity to consolidate, or at least refine delineation among pharmacists’ patient care service terminology. Usually, a profession’s name tends to be synonymous with the service: physical therapists provide “physical therapy,” phlebotomists “phlebotomize” and dentists provide “dentistry.” Even professions that have wide scope of practice fall back on a universal service term (e.g., nurses provide “nursing”). Perhaps by attempting to strictly define, explain and name pharmacist patient care services, the profession inadvertently caused serious misunderstanding. Perhaps the profession and patients would best be served if pharmacists just called what they do “pharmacy.” However, the pharmacy profession may be unable to fall back to this simplicity because the public’s recognition of the word “pharmacy” is highly associated with the noun meaning “store or building where drugs are dispensed.” The fact that the word “pharmacy” is associated with a place and product rather than a person is a major distinction between pharmacists and other healthcare providers. No other healthcare provider’s root word is associated with anything other than the person providing the service. Therefore, pharmacists have the unique challenge in delineating person from place and product.

Pharmacy’s Attempt to Standardizing Terminology

Partially due to pharmacy’s unique challenge in delineating person from place/product, the profession has seen a steady increase in service-term generation for nearly three decades. As such, the call to clarify, consolidate, and build consensus on standard service terminology has been raised for a number of years,9,12,13and the profession had made concerted effortsto address variation.14–16Most recent clarification efforts include the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners’ (JCPP) 2014Pharmacists’Patient Care Process (PPCP)17 which sought to define pharmacists’ consistent, uniform, and systematic process of care regardless of location, care setting, or patient population. Similarly,reconciliation between Comprehensive Medication Management and Pharmacist’s Patient Care Process has recently appeared in implementation research.18 However, despite these efforts, more service terms are likely to permeate the literature without the profession’s deliberate act to standardize terminology. For example, the term Enhanced Services rarely appears in current pharmacy practice literature, but its use (and misunderstanding) is expected to develop with the permeation of Community Pharmacy Enhanced Services Networks.

While standardization may be long desired among the majority of those in the profession, the actual process of creating consensus around standard service terminology is no minuscule task. Professions are left to regulate language themselves, as to date no US agency has the authority to standardize language in any healthcare profession, let alone pharmacy. In light of this, standardization of healthcare terminology is most likely far off. However, several key actions could be opportunities to move the pharmacy profession closer to standardization, including: (1) development of a national terminology classification system similar to other professions’ systems; (2) revision of MeSH terms; and (3) continued examination of PharmD accreditation standards.

Develop and Curatea Standardized Phraseology System Similar to Nursing’s Clinical Care Classification (CCC) System

Pharmacy is not the only healthcare profession to face misunderstanding and confusion regarding its terminology. In response to its own professional confusion, the American Nursing Association (ANA) developed a standardized system that codes discrete elements of nursing practice, called the Clinical Care Classification (CCC) System.19This terminology is the nationally recognized standard for all of the nursing profession and follows nurses’ process in all health care settings. The CCC System benefits nursing becauseit is recognized by the US Department of Health and Human Services and is used to develop standards and regulations related to nursing practice (e.g. documentation, quality improvement) and payment (e.g. SNOWMED-CT, ICD-10 codes).

Pharmacy has had similar, albeit comparatively small, success in influencing laws’ development with its professional terminology. For example, the term Collaborative Drug Therapy Management, coined by Zellmer et al in 199520 found its way into many state’s laws regarding Collaborative Practice Agreements. Therefore, it’s reasonable to believe that with further standardization, pharmacy could enjoy the benefits of professionally developed terms’ national recognition. However, to develop a nationally recognized standardized terminology classification system, unprecedented actions would need to take place. One first step would be to choose the systems’ framework, and as nursing’s CCC System is based off the nurses’ care process, it is reasonable to believe that JCPP’s Pharmacist Patient Care Process would serve as the framework for developing pharmacy’s future system. Further, as JCPP currently represents 13 different professional associations and works to develop consensus for the profession,21 it is reasonable to believe that JCPP could be an ideal leader for developing and curating this standard pharmacy terminology system.

Update and Adhere toMedical Subject Headings

Curated under the National Library of Medicine, the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) is a thesaurus used for indexing and searching articles on PubMED/MEDLINE. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses rely on MeSH terms to collate empirical evidence from multiple studies, and generate some of the highest level of evidence.22 However, systematic reviews and meta-analyses rely on unambiguous, relevant MeSH terms and review of pharmacy-practice related MeSH terms reveals ample room for clarification. Notwithstanding the lack of patient care service terms, if graduated from an ACPE-accredited school and licensed to practice, any pharmacist (regardless of location) has the “clinical training to provide patient centered, evidence based pharmaceutical care” as described under the MeSH term Clinical Pharmacists.23 Therefore, if MeSH terms were updated to reflect a standardized pharmacy service terminology classification system, it is reasonable to believe that health services researchers would be one step closer towards producing high-level, reliable evidence of pharmacists’ services.

As a unified profession, health service researchers, practicing pharmacists, and professional organizations alike would then need to make the commitment to promote and adhere to common terminology across research, practices, and time. As such, one way to promote adherence would be for journal editors and pharmacy health-service researchers alike have the responsibility to hold each other accountable to use these MeSH terms as keywords and refrain from developing new terms. Initially refraining from developing new terminology may sound counterproductive to innovation, but as this review has found the meaning of pharmacists’ service terms has not changed for decades; all terms’ definitions were a variation of “pharmacists’ use of their clinical knowledge to make a decision regarding a patient’s medication.”Of course, a standardized phraseology classification systems would require periodic updates, but only when the evidence implies an update is needed. By updating and adhering to MeSH terms that align with a standardized phraseology classification system, the profession could be one step closer to producing unvarying empirical evidence of pharmacists’ impact and value.

Clarification of Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience Accreditation Standards’ Focus from Setting to Service.

This review found no references to location among any of pharmacy’s patient-care service terms’ definitions. Similarly, in 1990, Hepler and Strand wrote “pharmaceutical care exist[s] regardless of practice setting.”5 However, pharmacists’ service terms continue to be commonly confused with location, as evidenced by MeSH term’s focus on location. Indeed, one common example includes the confusion of the terms “ambulatory” and “community” as either settings or services. On one hand the American Boards of Pharmacy Specialties (BPS) notes that ambulatory care is not setting-specific, but rather “healthcare services for ambulatory patients in a wide variety of settings, including community pharmacies, clinics and physician offices.”24On the other hand, confusion between setting and service might exist in the profession because PharmD educational accreditation standards for advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) are categorized via setting rather than service. Specifically, required APPEs are designated by four settings including hospital/health systems, inpatient general medicine, community, ambulatory.25As such, PharmD graduates must demonstrate competence in community and ambulatory care and to date, no guidance on what distinguishes a community practice/service from ambulatory care practice/service exists.

Recent efforts have been made to delineate pharmacists’ services from settings and update PharmD curriculum with practice changes. Recently, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s (AACP) developedthe Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs);26core EPAs are tasks that pharmacy graduates must be able to perform before entering practice and are required of all graduates regardless of practice setting.26 Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that if APPE standards could be clarified to reflect less on location and more towards services represented byEPAs, then the profession could be one step closer to clarifying the confusion between pharmacists’ services and pharmacists’ locations.

Recognition of Pharmacy’s Standardized Terminology in All of Healthcare

There is an urgent need for terminology standardization in the pharmacy profession. Confusion and variation in pharmacy practice terminology is not unique to patient care service terms, as this review has also contributed to the evidence that confusion exists between pharmacy settings and pharmacist services. However, terminology should be standardized to avoid confusion, misuse and misunderstanding not only in pharmacy, but all of healthcare. Specifically, it is important for a profession to have consensus and understanding within its own terminology, but it is arguably just as important for other healthcare professions to be aware of each other’s terminology as well. This is because standardization at its core is a safety issue. The third leading cause of death in the US is attributed to medical errors,27 and a leading root cause of these errors is communication problems.28 Variability in processes (like unstandardized language during communicating) are a known generator of problems like medical errors.

In an effort to improve communication, reduce variability and prevent errors, reliable organizations employ practices called “standardized phraseology.”Highly reliable organizations are high-risk organizations that operate for extended periods of time without serious accident;standardized phraseology is the universal recognition and use of one term for one meaning throughout an entire profession, regardless of role or location. Aviation, a type of highly reliable organization, pioneered standard phraseology after a communication error killed 600 people in the deadliest plane disaster of all time, resulting in the standard phrase “clear for takeoff” (in contrast, medical errors kill more than 600 people every day).29 Efforts to make healthcare emulate highly reliable organizations are encouraged from bodies like the US’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,30 and creation of standardized phraseology is a critical first step to these efforts.

LIMITATIONS

This review has several limitations. First, no singular body is recognized as the authority on pharmacy practice or its terminology, and therefore no validation of these findings can be made. Similarly, the authors of this review neither seek to posture nor claim to represent any unified voice of the profession. While the authors have expertise in pharmacist-provided services, this manuscript is limited to that expertise, including the characterization of the inclusion criteria “commonly misunderstood by pharmacists or other healthcare professionals, payers, government, regulatory entities and patients.” As such, it is possible that other terms related to pharmacist services would have differed slightly if other authors had been included in this review. Similarly, terms were excluded if the authors believed that one or a subset of the stakeholders mentioned above understood a term. If terms were included if commonly misunderstood by any stakeholder rather than all stakeholders, results would have differed. For example, the term “pharmacokinetics” can refer to services provided by a pharmacist in adjusting doses. While “pharmacokinetics” would not be readily recognized by patients, providers and pharmacists readily understand the term.

Second, meaning of words vary depending on context and time. It is likely that terms’ definitions exist outside of pharmacy practice and differ from those presented here, and while references generated from regulatory or government-affiliated sources were sought, only literature that applied to pharmacists were included. Therefore, this review’s findings may not be applicable to services delivered under the same name, albeit by any other healthcare professional aside from a pharmacist. Similarly, if sources of definitions unrelated to pharmacy practice (e.g. laymen’s dictionaries or searching of other healthcare professions’ literature) or literature published other than English was sought, it is likely that results would differ from the current findings. For example, if this review had expanded to include international literature, terminology appearing among counties’ socialized healthcare systems would have likely appeared.

In addition, the authors took liberty in determining synonyms. For example, the phrase Care Transitions was deemed synonymous with Transitions of Care, and the terms Pharmacogenomics and Pharmacogenetics were so close in meaning, that the authors presumed them functionally synonymous. Furthermore, terms that appeared as verbs to complete nouns were considered synonymous with the service noun. If synonyms and verbs were not grouped and rather definitions for each individual term were sought independently, results would likely differ. For example, Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process is a process and therefore a verb; if verbs were not considered synonymous with their service noun, then this term would have been excluded.

CONCLUSION

Common language is critical to clearly defining pharmacy’s culture and public image. Pharmacy would likely greatly benefit if it followed other healthcare professions’ example by convening with regulators, other clinician groups, payer groups and patient advocacy organizations alike to develop and curate a standardized phraseology classification system. Further, the profession has the responsibility to hold its members accountable when standardized terminology is omitted or misused, just as is practiced in highly reliable organizations. Overall, pharmacy’s move to standardize terminologywould likely improve communication among pharmacists (regardless of practice setting) and other health care professionals, increase visibility and understanding of pharmacists’ services,and ultimately improve the way pharmacy practice is studied.

“Certainly, a profession with a well-defined identity and a clearly articulated purpose has more to offer the commonweal than one that continues to be encapsulated in introspective factionalism.”

“We will not solve this problem by introspection. It will not help to clarify, list, or debate more functions for pharmacy. The element that is missing as we define our role during this period of transition is our conception of our responsibility to the patient. Some pharmacists have not yet identified patients care responsibilities commensurate with their extended functions, and the profession as a whole has made no clear social commitment that reflects its clinical functions. Some pharmacists will remain mired in the transitional period of professional adolescence until this step is taken.”

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Stephanie A. Gernant, University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy, 69 North Eagleville Road. Storrs, CT 06269-3092.

Jennifer L. Bacci, University of Washington School of Pharmacy 1959 NE Pacific Street. Seattle, WA 98195.

Charlie Upton, University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy, 69 North Eagleville Road. Storrs, CT 06269-3092.

Stefanie P. Ferreri, Practice Advancement and Clinical Education, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 301 Pharmacy Lane, CB 7475, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7475.

Stephanie McGrath, Pennsylvania Pharmacists Care Network, 5587 Baum Blvd, Floor 3, Pittsburgh, PA 15206.

Michelle A Chui, Sonderegger Research Center for Improved Medication Outcomes, University of Wisconsin-Madison, School of Pharmacy777 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53713.

Nathaniel M. Rickles, University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy, 69 North Eagleville Road. Storrs, CT 06269-3092.

Marie Smith, Dr. Henry A. Palmer Endowed Professor of Community Pharmacy Practice, University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy, 69 North Eagleville Road. Storrs, CT 06269-3092.

References

- 1.Giberson SYS, Lee MP ,. Improving Patient and Health System Outcomes through Advanced Pharmacy Practice. A Report to the U.S. Surgeon General. In: Office of the Chief Pharmacist. U.S. Public Health Service., ed2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. How Pharmacists Can Improve our Nation’s Health. In:2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker P The Hospital Pharmacist in the Clinical Setting. The Hospital Pharmacist’s Viewpoint. Second Annual Clinical Midyear Meeting of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists; December 4th, 1967, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birtcher KK, Corbett SM, Pass SE, et al. Symposium on roles of and cooperation between academic- and practice-based pharmacy clinicians. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2010;67(3):231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990;47(3):533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jorgenson D, Laubscher T, Lyons B, Palmer R. Integrating pharmacists into primary care teams: barriers and facilitators. Int J Pharm Pract 2014;22(4):292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutescu EA, Klotz RS. Basic terminology in obtaining reimbursement for pharmacists’ cognitive services. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2007;64(2):186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viswanathan M, Kahwati LC, Golin CE, et al. Medication therapy management interventions in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175(1):76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speedie MK, Anderson LJ. A consistent professional brand for pharmacy-the need and a path forward. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA 2017;57(2):256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. In. Pub. L. no. 101–508, 104 Stat 1388, 4401.,1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP guidelines on pharmacist-conducted patient education and counseling. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1997;54(4):431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotta I, Salgado TM, Silva ML, Correr CJ, Fernandez-Llimos F. Effectiveness of clinical pharmacy services: an overview of systematic reviews (2000–2010). Int J Clin Pharm 2015;37(5):687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGivney MS, Meyer SM, Duncan-Hewitt W, Hall DL, Goode JV, Smith RB. Medication therapy management: its relationship to patient counseling, disease management, and pharmaceutical care. JAPhA 2007;47(5):620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CMM in Primary Care Research Team. The Patient Care Process for Delivering Comprehensive Medication Management (CMM): Optimizing Medication Use in Patient-Centered, Team-Based Care Settings. 20018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renfro CP, Patti M, Ballou JM, Ferreri SP. Development of a medication synchronization common language for community pharmacies. JAPhA 2018;58(5):515–521.e511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bluml BM. Definition of medication therapy management: development of professionwide consensus. JAPhA 2005;45(5):566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process. 2014; https://jcpp.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/PatientCareProcess-with-supporting-organizations.pdf.

- 18.Blanchard C, Livet M, Ward C, Sorge L, Sorensen TD, McClurg MR. The Active Implementation Frameworks: A roadmap for advancing implementation of Comprehensive Medication Management in Primary care. Res Social Adm Pharm 2017;13(5):922–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saba VK, Taylor SL. Moving past theory: use of a standardized, coded nursing terminology to enhance nursing visibility. Comput Inform Nurs 2007;25(6):324–331; quiz 332–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zellmer WA. Collaborative drug therapy management. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1995;52(15):1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. About 2019; https://jcpp.net/about/.

- 22.Bob Phillips CB, Sackett Dave, Badenoch Doug, Straus Sharon, Haynes Brian, Dawes Martin. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of Evidence (March 2009). 1998; https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed August 2019.

- 23.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. PharmD Program Accreditation. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pharmd-program-accreditation/.

- 24.Board of Pharmacy Specialties. Ambulatory Care Pharmacy. https://www.bpsweb.org/bps-specialties/ambulatory-care/. Accessed Mary 2019.

- 25.Accreditation Council For Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. 2015; https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf.

- 26.Haines ST, Pittenger AL, Stolte SK, et al. Core Entrustable Professional Activities for New Pharmacy Graduates. Am J Pharm Educ 2017;81(1):S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. Bmj 2016;353:i2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Joint Commission. Patient Safety. Joint Comission Online 2015; https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/23/jconline_April_29_15.pdf. Accessed May 2019.

- 29.International Civil Aviation Organization. ICAO Standard Phraseology. A Quick Reference Guide for Commercial Air Transport Pilots. https://www.skybrary.aero/bookshelf/books/115.pdf.

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. High Reliability. Patient Safety Network: Patient Safety Primer https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/31/high-reliability. Accessed June,2019.

- 31.Francke GN. Evolvement of “clinical pharmacy”. 1969. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2007;41(1):122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):816–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Association AP. Principles of Practice for Pharmaceutical Care. 2018; https://www.pharmacist.com/principles-practice-pharmaceutical-care?is_sso_called=1. Accessed May 2018.

- 34.Social Security Act. In. Title XIX. Grants to States for Medical Assistance Programs. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. Drug Utilization Review. 2009; https://www.amcp.org/about/managed-care-pharmacy-101/concepts-managed-care-pharmacy/drug-utilization-review. Accessed Mary 2018.

- 36.Straka RJ, Marshall PS. The Clinical Significance of the Pharmacogenetics of Cardiovascular Medications. Journal of pharmacy practice. 1992;5(6):337–361. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reiss SM. Integrating pharmacogenomics into pharmacy practice via medication therapy management. JAPhA 2011;51(6):e64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tett SE, Higgins GM, Armour CL. Impact of pharmacist interventions on medication management by the elderly: a review of the literature. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 1993;27(1):80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Medication Management Services (MMS) Definition and Key Points. 2018; https://jcpp.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Medication-Management-Services-Definition-and-Key-Points-Version-1.pdf. Accessed May, 2018.

- 40.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. Practice Advisory on Collaborative Drug Therapy Management. 2012; https://www.amcp.org/sites/default/files/2019-03/Practice%20Advisory%20on%20CDTM%202.2012_0.pdf.

- 41.Goldenberg RI, Bell SH, Wright J, et al. HIV Continuum of Care: Challenges in Management. Journal of Home Health Care Practice. 1996;8(6):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Joint Commission. Transitions of Care: The need for a more effective approach to continuing patient care. Hot Topics in Health Care 2012; https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Hot_Topics_Transitions_of_Care.pdf.

- 43.Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. In:2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Pharmacists Association; National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication therapy management in pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service model (version 2.0). JAPhA 2008;48(3):341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Alert. 2006; https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_35.pdf. [PubMed]

- 46.US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Eligible Professional Meaningful Use Menu Set Measures In: EHR Incentive Program, ed. Measure 7 of 10. Stage 1. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CY 2018 Medication Therapy Management Program Guidance and Submission Instructions. In:2017. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pagano GM, Groves BK, Kuhn CH, Porter K, Mehta BH. A structured patient identification model for medication therapy management services in a community pharmacy. JAPhA 2017;57(5):619–623.e611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Integrating Comprehensive Medication Management to Otimize Patient Outcomes. 2012; Second Edition. https://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/media/medmanagement.pdf.

- 50.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Comprehensive Medication Management in Team-Based Care. 2016; https://www.accp.com/docs/positions/misc/CMM%20Brief.pdf.

- 51.US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Care Management Services. 2016; https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/ChronicCareManagement.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fixen DR, Linnebur SA, Parnes BL, Vejar MV, Vande Griend JP. Development and economic evaluation of a pharmacist-provided chronic care management service in an ambulatory care geriatrics clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(22):1805–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]