Abstract

Objective

To determine reversion rates from chronic migraine to episodic migraine during long-term erenumab treatment.

Methods

A daily headache diary was completed during the 12-week, double-blind treatment phase of a placebo-controlled trial comparing erenumab 70 mg, 140 mg, and placebo, and weeks 1–12, 21–24, 37–40, and 49–52 of the open-label treatment phase. Chronic migraine to episodic migraine reversion rates were assessed over the double-blind treatment phase; persistent reversion to episodic migraine over 24 weeks (double-blind treatment phase through the first 12 weeks in the open-label treatment phase), long-term persistent reversion to episodic migraine over 64 weeks (double-blind treatment phase plus open-label treatment phase); delayed reversion to episodic migraine through the first 12 weeks of the open-label treatment phase among patients remaining in chronic migraine during the double-blind treatment phase.

Results

In the double-blind treatment phase, 53.1% (95% confidence interval: 47.8–58.3) of 358 erenumab-treated completers had reversion to episodic migraine; monthly reversion rates to episodic migraine were typically higher among patients receiving 140 mg versus 70 mg. Among 181 completers (receiving erenumab for 64 weeks), 98 (54.1% [95% confidence interval: 46.6–61.6]) had reversion to episodic migraine during the double-blind treatment phase; of those, 96.9% (95% confidence interval: 91.3–99.4) had persistent reversion to episodic migraine, 96.8% (95% confidence interval: 91.1–99.3) of whom had long-term persistent reversion to episodic migraine. Delayed reversion to episodic migraine occurred in 36/83 (43.4% [95% confidence interval: 32.5–54.7]) patients; of these, 77.8% (95% confidence interval: 60.9–89.9) persisted in reversion through week 64.

Conclusions

Patients with reversion to episodic migraine at week 12 will likely persist as episodic migraine with longer-term erenumab; others may achieve delayed reversion to episodic migraine.

Clinical trial registration: URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT02066415

Keywords: Calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor, erenumab, migraine prophylaxis, transformed migraine

Introduction

Migraine is the world’s second leading medical cause of disability, and the leading cause of disability among girls and women aged 10–49 years of age (1,2). Although there are many approaches to classifying migraine, the distinction between episodic migraine (EM) and chronic migraine (CM) is useful. CM is defined, in part, by the occurrence of headache on ≥15 days per month for >3 months, with ≥8 days/month linked to migraine (3). EM is the complement of CM. Based on this categorical boundary, if the monthly headache frequency decreases to <45 days for ≥12 weeks, we consider this a reversion from CM to EM. Population-based studies have shown that, in comparison with EM, people with CM have a greater disease burden, more disability, more impairment in health-related quality of life, and higher direct and indirect costs (4–7).

It is not uncommon for individual patients to progress from EM to CM (8); studies have reported that the annual rate of transitioning from EM to CM is about 2.5% in population studies and as high as 14% in clinic-based studies (9–11). The rate of reversion of CM to EM has been reported to be higher (12,13). An important treatment goal for patients with CM is a reduction in headache frequency, including the categorical reversion of CM to EM, but more detailed data on rates of reversion have rarely been reported. Factors associated with reversion of CM to EM include the absence of allodynia and no medication overuse (12,14); conversely, comorbid pain disorders other than migraine, higher frequency of headache days, and the presence of allodynia have been associated with lower reversion of CM (12,13).

Erenumab (in the USA, erenumab-aooe) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that specifically inhibits the canonical calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor (15). Erenumab is approved in the USA and the European Union for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults (16,17). Subcutaneous erenumab 70 mg or 140 mg monthly has been demonstrated to reduce monthly migraine days (MMDs) and improve measures of migraine-related disability in patients with EM and CM (18–21). To translate these previously reported measures into more clinically relevant outcomes, we assess the achievement of reversion from CM to EM for various periods of time defined in the Methods section. The state of reversion that is associated with treatment is provisional, as there conceivably might be movement back to CM (8).

To assess the rates of reversion from CM to EM over 12 weeks (i.e. a reduction in headache day frequency while on treatment to <45 headache days over 12 weeks), we performed a post-hoc analysis of a 12-week, placebo-controlled trial of patients with CM (20), and a subsequent 52-week, open-label extension study.

Methods

Study design

Details of the study design for the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial have been previously reported (20). Patients were randomized 3:2:2 to receive monthly placebo, erenumab 70 mg, or erenumab 140 mg subcutaneously over a 12-week double-blind treatment phase (DBTP). Patients were eligible for entry into the 52-week open-label extension if they completed the DBTP, were deemed appropriate for continued treatment by the investigator, and provided separate informed consent.

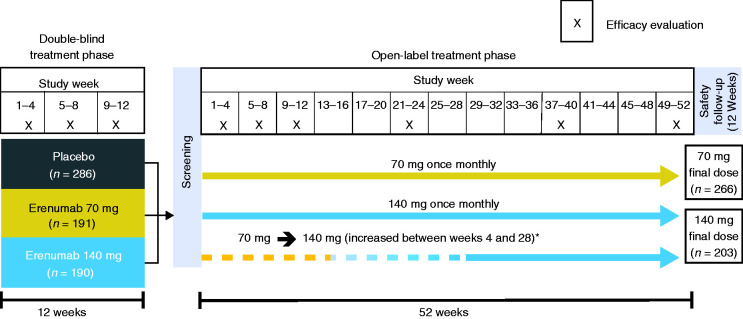

In the 12-week DBTP and the subsequent 52-week open-label treatment phase (OLTP), patients received treatment monthly (i.e. every 4 weeks for up to 64 weeks in total). Headache information was collected daily during the 4 weeks before baseline, the entire 12-week DBTP (20); and over the first 12 weeks and weeks 21–24, 37–40, and 49–52 of the OLTP. The initial erenumab dose used in the OLTP was 70 mg once monthly; however, a protocol amendment increased the dose to 140 mg monthly for patients who had not completed the week 28 visit so that they would have the opportunity to receive erenumab 140 mg for ≥24 weeks before study end (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

*Following a protocol amendment, patients who had not yet reached week 28 had their dose increased to 140 mg.

All institutional review boards and independent ethics committees at the various sites approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Outcomes

Patients used an electronic diary to enter daily information about headache, including time of onset, time to resolution, pain severity, pain features, headache/migraine symptoms, and use of acute headache medications. An algorithm was used to determine which days qualified as migraine days and headache days. The qualifications for a migraine day and headache day have been previously described (20).

The term “reversion from CM to EM” was chosen to identify patients who moved from ≥15 headache days per month (required in the study for the diagnosis of chronic migraine) to <15 headache days per month (referred to as episodic migraine). CM to EM reversion observed during the time periods of assessment is considered provisional as there conceivably might be movement back to CM.

Monthly reversion to EM (i.e. patients moving to <15 headache days per month [4-week period]) was assessed during weeks 1–4, 5–8 and 9–12 of the DBTP, and also during weeks 9–12, 21–24, 37–40 and 49–52 of the OLTP in all patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of definitions used for reversion from CM to EM.

| Requirement for eligibility to achieve this endpoint | Time period assessed (study phase) | Criteria for reversion from CM to EM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly reversion | None | Any 4-week period* | <15 headache days |

| Reversion | None | Weeks 1–12 (DBTP*) | <45 headache days |

| Persistent reversion | Reversion in DBTP | Weeks 1–12 (OLTP†;‡) | <45 headache days |

| Long-term persistent reversion | Persistent reversion | Weeks 21–24, 37–40, and 49–52 (OLTP†,§) | <45 headache days over the combined assessment periods |

| Delayed reversion | No reversion in DBTP | Weeks 1–12 (OLTP†,‡) | <45 headache days |

| Delayed long-term reversion | Delayed reversion | Weeks 21–24, 37–40, and 49–52 (OLTP†,§) | <45 headache days over the combined three 4-week assessment periods |

| Long-term reversion | None | Weeks 1–12‡, 21–24; 37–40, and 49–52§ (OLTP†) | <45 headache days over weeks 1–12 and over the combined three 4-week assessment periods |

CM: chronic migraine; DBTP: double-blind treatment phase; OLTP: open-label treatment phase.

*Missing data imputed as non-response.

†Assessed only in patients who received erenumab during the DBTP and had complete monthly headache day data for all applicable assessment periods.

‡Weeks 13–24 of erenumab treatment.

§Note week 52 of the OLTP is week 64 of erenumab treatment.

Reversion to EM over 12 weeks of treatment was defined as patients with <45 headache days over the 12-week period of the DBTP. Persistent reversion to EM over 24 weeks of treatment was defined as those with reversion over the 12-week period of the DBTP who continued to meet the criteria for reversion over the subsequent 12-week period of the OLTP (i.e. < 45 headache days over both 12-week periods). Long-term persistent reversion to EM over 64 weeks of treatment was defined as reversion over each of the following: the 12-week period of the DBTP, the first 12-week period of the OLTP, and over the combined three 4-week periods of the OLTP (weeks 21–24, 37–40, and 49–52; i.e. <45 headache days over the combined 12-week period).

Delayed reversion to EM was defined as patients treated with erenumab who continued to have CM after 12 weeks of treatment at the end of the DBTP, but subsequently met the criteria for reversion after continuing erenumab treatment through the first 12 weeks of the OLTP. Delayed long-term reversion to EM over 52 weeks for those with delayed reversion was defined as reversion over the first 12 weeks of the OLTP and over the combined three 4-week periods of the OLTP during weeks 21–24, 37–40, and 49–52. Long-term reversion over 52 weeks includes completers with reversion during each assessment period of the OLTP (the first 12-week period, and the combined three 4-week periods) regardless of their reversion status at the end of the DBTP.

Statistical analyses

These post-hoc analyses were primarily descriptive, with dichotomous variables reported as counts and percentages (95% CI). Demographic data were presented as mean (SD). The reversion analyses during the DBTP and OLTP were based on headache diary data. Missing diary data were handled using proration approach; monthly headache days and monthly migraine days were calculated if patients completed ≥50% of their daily diary reporting each month. If patients had completed <50% of daily diary reporting, monthly headache days and monthly migraine days were set as missing. Reversion outcomes were only assessed for patients who had non-missing monthly headache days in each month during the 12-week periods. For the monthly and overall reversion analyses during the 12-week DBTP, adjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and associated p-values were obtained from a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by region (North America vs. Others) and medication overuse status after missing data were imputed as non-response. Nominal statistical significance was determined when p < 0.05 without adjustment for multiplicity. The reversion analyses during the OLTP were descriptive only. Outcomes at weeks 40 and 52 of the OLTP were analysed by the last dose received because patients who switched dose from erenumab 70 mg to 140 mg at or prior to week 28 would have achieved steady state with erenumab 140 mg by week 40 and received at least 24 weeks of erenumab 140 mg by week 52. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient disposition

The post-hoc analysis included 656 subjects from the previously reported randomized, 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled parent trial of patients with CM (20). Overall, 637 patients (97.1%) completed the DBTP (20). Of these, 609 patients entered the 52-week OLTP: 549 patients started on erenumab 70 mg, and 60 started on erenumab 140 mg. Of the patients who started on erenumab 70 mg, 199 switched to erenumab 140 mg at the week 28 visit or earlier. During the OLTP, 139 patients (22.8%) discontinued treatment. The most common reasons for discontinuation were patient request (n = 64, 10.5%) and lack of efficacy (n = 39, 6.4%). Of the 609 patients enrolled in the 52-week OLTP, 351 (57.6%) patients had received erenumab 70 mg (n = 175) or 140 mg (n = 176) in the DBTP.

Reversion to EM in the DBTP

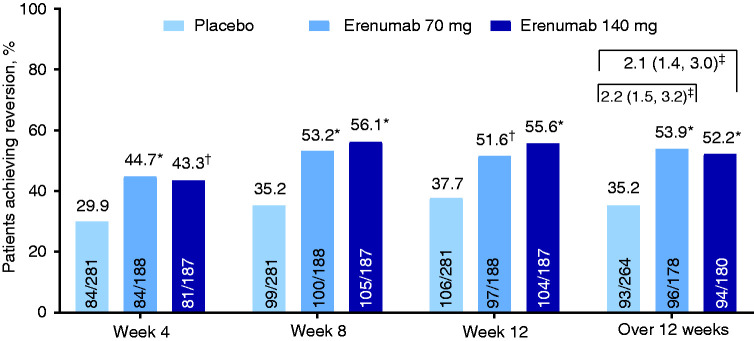

The proportion achieving monthly reversion to EM assessed during weeks 1–4 of the DBTP in those receiving placebo, erenumab 70 mg, and erenumab 140 mg were 29.9%, 44.7% and 43.3%, respectively (Figure 2); odds ratio (OR) versus placebo were 1.9 (95% CI: 1.3–2.9) for erenumab 70 mg and 1.8 (95% CI: 1.2–2.6) for erenumab 140 mg. Monthly reversion rates to EM during weeks 5–8 were 35.2%, 53.2%, and 56.1%, respectively (OR vs. placebo of 2.1 [95% CI: 1.5–3.1] and 2.4 [95% CI: 1.6–3.5], respectively), and those during weeks 9–12 were 37.7%, 51.6%, and 55.6% respectively (OR vs. placebo of 1.8 [95% CI: 1.2–2.6] and 2.1 [95% CI: 1.4–3.1], respectively). Aligning with the findings of the primary analysis, monthly reversion rates to EM were statistically higher in the erenumab groups compared with the placebo group at each monthly assessment period.

Figure 2.

Monthly and overall rates of reversion from chronic migraine to episodic migraine during the double-blind treatment phase.

*p < 0.001 compared with placebo.

†p = 0.003 compared with placebo.

‡Odds ratio (95% CI) versus placebo.

Twelve weeks may be a more relevant period for assessment of reversion from CM to EM, because monthly fluctuations in headache frequency may not represent a meaningful treatment-related categorical change (8). Among patients receiving placebo, erenumab 70 mg, and erenumab 140 mg, 35.2%, 53.9% and 52.2%, respectively, attained reversion to EM over weeks 1–12 of the DBTP. Treatment with either erenumab dose was associated with increased likelihood of reversion to EM compared with placebo; OR versus placebo were 2.2 (95% CI: 1.5–3.2) for erenumab 70 mg and 2.1 (95% CI: 1.4–3.0) for erenumab 140 mg. Across all erenumab recipients, 190/358 (53.1% [95% CI: 47.8–58.3]) achieved reversion to EM (Figure 2).

Some baseline demographic and clinical features of patients who attained reversion from CM to EM over weeks 1–12 of the DBTP differed from those of patients who remained in CM over the same period (Table 2). For example, patients that reverted from CM to EM over 12 weeks of the DBTP had fewer baseline monthly headache days and MMDs, and less prior failure of migraine preventive treatment(s), compared with those who remained in CM. The number of monthly acute migraine-specific medication days at baseline was similar in EM reverters versus non-reverters.

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of CM patients by reversion status after the 12-week, double-blind treatment phase.

| Patients with reversion in the DBTP (reverters)* |

Patients remaining in CM in the DBTP (non-reverters) † |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 93) |

Erenumab 70 mg (n = 96) |

Erenumab 140 mg (n = 94) |

Placebo (n = 171) | Erenumab 70 mg (n = 82) |

Erenumab 140 mg (n = 86) |

|

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 41.8 (11.9) | 41.6 (10.5) | 44.2 (11.1) | 42.2 (11.2) | 41.5 (12.2) | 41.9 (10.9) |

| Min, max | 20, 66 | 18, 62 | 18, 64 | 18, 64 | 18, 64 | 19, 64 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 74 (79.6) | 84 (87.5) | 78 (83.0) | 139 (81.3) | 72 (87.8) | 77 (89.5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 86 (92.5) | 87 (90.6) | 90 (95.7) | 162 (94.7) | 78 (95.1) | 84 (97.7) |

| Black or African American | 5 (5.4) | 6 (6.3) | 4 (4.3) | 4 (2.3) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.3) |

| Asian | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (2.4) | 0 |

| Other‡ | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Monthly headache days, mean (SD) | 19.0 (2.8) | 18.5 (2.7) | 19.5 (3.2) | 22.5 (3.7) | 23.1 (3.3) | 22.1 (3.8) |

| Monthly migraine days, mean (SD) | 16.2 (3.6) | 16.2 (3.3) | 16.5 (4.2) | 19.5 (4.7) | 20.1 (4.4) | 19.2 (4.9) |

| Monthly acute migraine-specific medication days, mean (SD) | 8.5 (5.9) | 8.8 (7.1) | 10.3 (6.5) | 10.0 (8.2) | 9.0 (7.4) | 9.5 (7.5) |

| Prior migraine preventive treatment failure, n (%) | 56 (60.2) | 59 (61.5) | 63 (67.0) | 129 (75.4) | 58 (70.7) | 60 (69.8) |

CM: chronic migraine; DBTP: double-blind treatment phase.

*For the DBTP, patients with reversion from CM to EM were defined as patients with < 45 headache days over the 12-week period.

†For the DBTP, patients remaining in CM were defined as patients with ≥ 45 headache days or patients with any missing monthly headache day data over the 12-week period.

‡Included American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, individuals of multiple ethnic origins, and Other.

Reversion to EM in the OLTP

In patients who received erenumab in the OLTP following either placebo or erenumab during the DBTP, monthly reversion from CM to EM occurred in 359/560 (64.1% [95% CI: 60.0–68.1]) of patients during weeks 9–12, 327/481 (68.0% [95% CI: 63.6–72.1]) during weeks 21–24, 296/430 (68.8% [95% CI: 64.2–73.2]) during weeks 37–40 and 276/383 (72.1% [95% CI: 67.3–76.5]) during weeks 49–52 of the OLTP.

Among the 284 patients treated with erenumab for at least 24 weeks since the beginning of the DBTP (i.e. during the DBTP and for the first 12 weeks of the OLTP) and having complete monthly headache day data, 154/284 (54.2% [95% CI: 48.2–60.1]) achieved reversion to EM over the 12 weeks of the DBTP. Of those with EM reversion over the DBTP, persistent reversion to EM occurred in 144/154 (93.5% [95% CI: 88.4–96.8]), as assessed over weeks 1–12 of the OLTP.

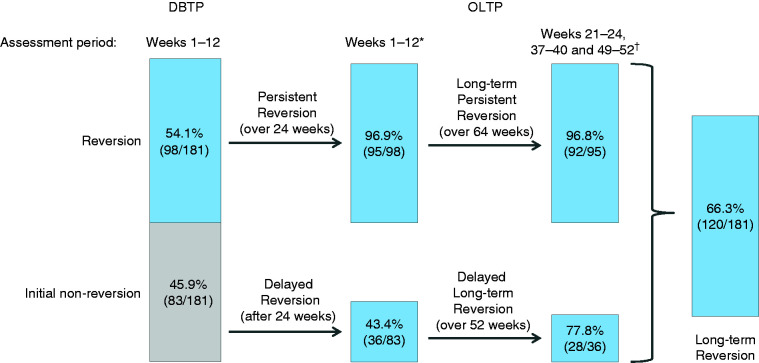

Of the 181 patients treated with erenumab for the entire 64 weeks (i.e. during the DBTP and the entire OLTP), 98/181 (54.1% [95% CI: 46.6–61.6]) had reversion from CM to EM as assessed over weeks 1–12 of the DBTP. Of those 98 patients, persistent EM reversion over weeks 1–12 of the OLTP (i.e. after 24 weeks of treatment) occurred in 95/98 (96.9% [95% CI: 91.3–99.4]), and of those long-term persistent EM reversion through the last three 4-week assessment periods combined (i.e. < 45 headache days over weeks 21–24, weeks 37–40 and weeks 49–52) of the OLTP (i.e. after 64 weeks of treatment) occurred in 92/95 (96.8% [95% CI: 91.1–99.3]; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Classification of attaining reversion from chronic migraine to episodic migraine (i.e. < 45 headache days per 12 weeks) during the OLTP in patients treated with erenumab who had reversion to episodic migraine at week 12 of the DBTP and who had complete monthly headache day data for the entire study period.

DBTP: double-blind treatment phase; OLTP: open-label treatment phase.

*After 24 weeks of erenumab treatment.

†After 64 weeks of erenumab treatment.

Analysis of the 284 patients who completed 24 weeks of erenumab (i.e. the DBTP and through the first 12 weeks of the OLTP) demonstrated that 130/284 of patients (45.8%) remained in CM over the DBTP; of those, 45/130 (34.6% [95% CI: 26.5–43.5]) had delayed reversion to EM after continuing erenumab over the first 12 weeks of the OLTP. Based on the completer analysis (i.e. all patients who completed the DBTP and OLTP), of the 83/181 patients (45.9% [95% CI: 38.4–53.4]) who remained in CM over the 12 weeks of the DBTP, 36/83 (43.4% [95% CI: 32.5–54.7]) had delayed reversion to EM over the first 12 weeks of the OLTP. Of those who had delayed reversion, 28/36 (77.8% [95% CI: 60.9–89.9]) remained in EM reversion through the 52-week OLTP (delayed long-term EM reversion) as assessed by the combined last three 4-week assessment periods of the OLTP. Regardless of their reversion status at the end of the DBTP, among all patients who received erenumab for 64 weeks and had complete monthly headache day data during both DBTP and OLTP, 120/181 (66.3% [95% CI: 58.9–73.1]) remained as EM reverters through the 52-week OLTP as assessed over weeks 1–12 of the OLTP and over the combined last three 4-week assessment periods of the OLTP (long-term EM reversion).

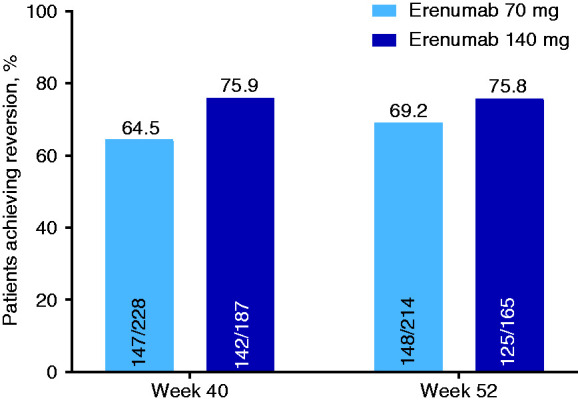

Based on the last dose of erenumab received among completers during the OLTP, higher monthly reversion to EM was achieved in patients receiving erenumab 140 mg versus those receiving erenumab 70 mg. Monthly EM reversion rates were 75.9% (95% CI: 69.2–81.9) for erenumab 140 mg and 64.5% (95% CI: 57.9–70.7) for the 70-mg dose at week 40 (i.e. during weeks 37–40 of the OLTP); and 75.8% (95% CI: 68.5–82.1) versus 69.2% (95% CI: 62.5–75.3), respectively, at week 52 (i.e. during weeks 49–52 of the OLTP; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Monthly reversion to episodic migraine assessed in the 4-week periods before weeks 40 and 52 of the OLTP by last erenumab dose (overall population).

Discussion

In the primary analysis of a pivotal placebo-controlled trial of erenumab in patients with CM, the percentage of patients achieving at least a 50% reduction in MMDs was significantly higher for erenumab 70 mg (39.9%) and erenumab 140 mg (41.2%) than for placebo (23.5%), as was the mean reduction in monthly migraine days (erenumab 70 mg and 140 mg: both −6.6 days; placebo: −4.2 days) (20). In the present post-hoc analysis of this trial, the rates of categorical reversion from CM to EM (i.e. headache frequency reduced to <45 headache days over 12 weeks) over the 12-week DBTP were slightly higher than the 50% responder rates. Nonetheless, as observed with 50% responder rates, rates of categorical reversion to EM for erenumab 70 mg (53.9%) and erenumab 140 mg (52.2%) were significantly higher than that for placebo (35.2%). A comparison of baseline characteristics suggested several potential differences between reverters and non-reverters in the DBTP. Consistent with previous findings (12), patients with reversion to EM had fewer monthly headache days compared with non-reverters at baseline, supporting that those with baseline headache frequency closer to the categorical boundary (i.e. <15 headache days per month) were more likely to fall below the boundary on follow-up. This finding is also consistent with studies that showed an association between progression from EM to CM and the number of monthly headache days at baseline (12,14). Others have reported that reversion from CM to EM is associated with less frequent acute medication overuse and conversely that preventive medication use is associated with remaining in CM (12,14). This may result from confounding by indication; since a minority of patients with migraine receive preventive treatment, factors associated with the decision to offer preventive treatment may also be associated with a lower reversion rate from CM to EM. In this analysis, patients who had reversion to EM were less likely to have experienced a failure of other preventive medications.

Reversion to EM with erenumab was sustained through 1 year in the OLTP. Of patients who attained EM reversion through the first 12 weeks of treatment on erenumab, and who continued on treatment during the OLTP for 52 weeks (i.e. 64 weeks of total treatment), 96.9% achieved persistent EM reversion over 24 weeks and of those, 96.8% achieved long-term persistent EM reversion over 64 weeks. This indicates that the achievement of early reversion to EM is often sustained with long-term treatment. Further, patients achieving persistent EM reversion over 24 weeks had a mean (SD) reduction in MMDs from parent study baseline of 10.3 (4.6) days, and those achieving long-term persistent EM reversion over 64 weeks had a mean (SD) reduction in MMDs from parent study baseline of 11.4 (4.7) days, indicating that the reversion to EM was associated with a substantial reduction in monthly migraine days.

Importantly, we also found that among study completers who remained in CM after the initial 12 weeks of therapy (those who did not achieve reversion to EM in the DBTP), 43.4% attained delayed reversion to EM over the next 12 weeks of therapy. When all patients completing the first 12 weeks of treatment of the OLTP were considered, 34.6% of those remaining in CM over the DBTP attained delayed reversion. We cannot know what would have happened to the patients who did not revert to EM during the 12 weeks of the DBTP and subsequently discontinued erenumab treatment during the OLTP. However, it seems probable that those who did not experience headache frequency reduction with erenumab would be more likely to discontinue treatment; if so, these may be over-estimates of the rate of delayed EM reversion. Similarly, others have reported a reduction in headache days to <15 days per month after a second onabotulinumtoxinA treatment cycle in a real-world analysis (22) and in a post-hoc analysis of pooled data from the PREEMPT clinical trials; these studies evaluated the efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine (23).

Given the natural fluctuation in headache days over time (8), in the current report we determined whether patients who attained delayed reversion to EM remained as EM with treatment through the remainder of the OLTP. A total of 77.8% of those patients who had delayed reversion remained as EM reverters, suggesting that the delayed reversion to EM may have been due to effective drug treatment rather than natural fluctuation. Similarly, in patients who did not respond to a first treatment cycle of onabotulinumtoxinA, reversion rates from CM to EM (<15 headache days per month) after four cycles of onabotulinumtoxinA treatment were 54% at 12 months, and 66% at 15 months (22). Discontinuing erenumab in patients with CM who do not revert over 12 weeks may deprive patients of benefits that develop with delay. Ultimately, it would be useful to develop decision rules for stopping or continuing erenumab and other monoclonal antibodies after a 12-week trial. Treatment would be continued in those with clear benefit and in those likely to develop benefits and discontinued in those for whom a clinically meaningful benefit is unlikely.

Regardless of the initial status after 12 weeks of treatment, 66.3% of all completers receiving erenumab throughout the 64-week treatment period had a long-term reversion to EM throughout the assessment periods of the OLTP. Preliminary reports indicate that similar results may be observed with both galcanezumab and fremanezumab treatment of patients with CM after 12 months, with 65.1% and 67.4% of patients, respectively, reverting to <15 headache days per month in those receiving treatment for the entire 12-month period (24,25). In our study, numerically more patients who had received erenumab 140 mg for ≥24 weeks at the end of the OLTP attained reversion to EM at week 52 (75.8%) than those who received erenumab 70 mg (69.2%).

Limitations

The pivotal double-blind trial on which this post-hoc analysis was based has previously been acknowledged as a high-quality trial with a low risk of bias (26). However, the OLTP study was not blinded, did not have a placebo-control group, and patients were not re-randomized to the 70 mg or 140 mg dose, potentially introducing bias and limiting the ability to compare outcomes between dose groups. In addition, attrition is inevitable in long-term studies and may have an impact on the overall outcomes. As discussed in previous reports of the double-blind trial, patients with comorbidities such as fibromyalgia and poorly controlled hypertension were not eligible for enrolment in the double-blind trial, and were therefore not included in the OLTP study, limiting the generalizability of the study results to the broader migraine population (20).

Further, this was a post-hoc analysis, and as such, results should be interpreted cautiously. Dose-specific CM to EM reversion rates and efficacy data were based on 4-week headache day data and may not be representative of outcomes based on 12-week headache day data. This analysis assessed reversion to EM based on a categorical classification (i.e. <15 headache days per month, or <45 headache days per 12 weeks) based on the current International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) definitions (3). The <45 headache days per 12 weeks definition was used to identify those patients who, on average, had <15 headache days per month in the 3-month period assessed (which was not continuous), and these patients were categorized as having attained reversion to EM. It is acknowledged that patients could potentially meet the definition of EM reversion (e.g. 44 headache days over 12 weeks) and have ≥15 headache days per month for 2 of the 3 months being assessed (e.g. 13 headache days in month 1, 15 headache days in month 2, 16 headache days in month 3). Further, patients with a baseline headache frequency close to the categorical boundary (i.e. ≥15 headache days/month) could be classified as attaining reversion from CM to EM with only a small reduction in headache days. However, patients reverting to EM had a mean reduction in headache days from a baseline of > 10 days/month, suggesting the change was clinically meaningful. Categorical change of EM to CM or CM to EM is just one approach that can be used to assess the benefit of treatment. While this approach is clinically intuitive and linked to diagnostic criteria, it is in a sense crude as it takes into account just two possible categorical states. Continuous variable change is more consistent with clinical reality and has higher statistical power but, since migraine research, regulatory decisions, and the headache literature have all used categorical changes for EM and CM, this approach was adopted in this analysis. Other types of categorical changes in headache frequency or even composite endpoints may be considered for future analyses.

Finally, in patients with CM and a high frequency of headache days per month, the relative change in headache or migraine days from baseline, or a ≥50% reduction in headache or migraine days from baseline, could have been considered as an alternative approach to assess the efficacy of preventive treatment(s) (27). Using this approach, other investigators have previously demonstrated the efficacy of erenumab over 12 weeks and up to 64 weeks (18,19,28). Notwithstanding these limitations, erenumab treatment appears to result in a provisional long-term reversion from CM to EM over a 64-week period, with erenumab 140 mg having numerically greater efficacy than the 70 mg dose.

Conclusions

A post-hoc analysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and the open-label extension demonstrated that monthly treatment with erenumab 70 mg or 140 mg reduced migraine frequency with reversion from CM to EM in more than 50% of patients at the end of the 12-week DBTP. Of those completers who attained reversion to EM at the end of the DBTP, more than 95% had persistent reversion over 24 weeks and more than 90% experienced long-term persistent reversion over a 52-week OLTP for a total of 64 weeks of treatment. Delayed reversion to EM was also common, with more than 40% of initial non-reverters (i.e. those remaining in CM after 12 weeks of the DBTP) attaining delayed reversion to EM with continued treatment 24 weeks after starting erenumab. Overall, 66% of patients completing 64 weeks of treatment with erenumab attained reversion and remained as EM throughout the OLTP of the study.

Clinical implications

Categorical reversion from chronic migraine (CM) to episodic migraine (EM) is an important treatment goal in patients with chronic migraine.

Treatment with erenumab 70 mg and 140 mg monthly is associated with greater rates of reversion than placebo after 12 weeks; reversion rates up to 64 weeks are higher in those receiving erenumab 140 mg versus those receiving the 70 mg dose.

Of patients who attained reversion to EM after 12 weeks and who completed the study, 94% remained as EM with ongoing treatment for up to 64 weeks.

More than 40% of patients who were classified as having CM in the first 12 weeks may attain delayed reversion to EM after a total of 24 weeks ongoing treatment.

Overall, approximately two-thirds of patients with CM receiving erenumab are likely to attain reversion to EM and persist in this state after 64 weeks of treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Julie Wang (Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) and Lee Hohaia (ICON, North Wales, PA, USA), whose work was funded by Amgen Inc., for medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript, and Andrea Wang (Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) for critical review of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement: Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at http://www.amgen.com/datasharing.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: RBL is the Edwin S. Lowe Professor of Neurology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. He receives research support from the NIH: 2PO1 AG003949 (mPI), 5U10 NS077308 (PI), R21 AG056920 (Investigator), 1RF1 AG057531 (Site PI), RF1 AG054548 (Investigator), 1RO1 AG048642 (Investigator), R56 AG057548 (Investigator), U01062370 (Investigator), RO1 AG060933 (Investigator), RO1 AG062622 (Investigator), 1UG3FD006795 (mPI), 1U24NS113847 (Investigator), K23 NS09610 (Mentor), K23AG049466 (Mentor), K23 NS107643 (Mentor). He also receives support from the Migraine Research Foundation and the National Headache Foundation. He serves on the editorial board of Neurology, senior advisor to Headache, and associate editor to Cephalalgia. He has reviewed for the NIA and NINDS, holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics and Biohaven Holdings; serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received honoraria from: American Academy of Neurology, Allergan, American Headache Society, Amgen, Avanir, Biohaven, Biovision, Boston Scientific, Dr. Reddy’s (Promius), Electrocore, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, Equinox, GlaxoSmithKline, Lundbeck (Alder), Merck, Pernix, Pfizer, Supernus, Teva, Trigemina, Vector, and Vedanta. He receives royalties from Wolff’s Headache 7th and 8th Edition, Oxford University Press, 2009, Wiley, and Informa.

SJT reports serving as editor of Headache Currents and board member for American Headache Society; serving as consultant for Acorda, Alder, Alexsa, Align Strategies, Allergan, Alphasights, Amgen, Aperture Venture Partners, Aralez Pharmaceuticals Canada, Axsome, Becker Pharmaceutical Consulting, BioDelivery Sciences International, Biohaven, Charleston Labs, Currax, Decision Resources, DeepBench, Dr. Reddy’s, electroCore, Eli Lilly, eNeura, Equinox, ExpertConnect, GLG, GlaxoSmithKline, Guidepoint Global, Healthcare Consultancy Group, Impel, M3 Global Research, Magellan Rx Management, Marcia Berenson Connected Research and Consulting, Medicxi, Navigant Consulting, Neurolief, Nordic BioTech, Novartis, Pfizer, Reckner Healthcare, Relevale, Revance, Satsuma, Scion Neurostim, Slingshot Insights, Sorrento, Spherix Global Insights, Sudler and Hennessey, Synapse Medical Consulting, Teva, Theranica, Thought Leader Select, Trinity Partners, XOC, and Zosano; speaking for or receiving honoraria from American Academy of Neurology, American Headache Society, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Diamond Headache Clinic, Elsevier, Forefront Collaborative, Hamilton General Hospital, Headache Cooperative of New England, Henry Ford Hospital, Inova, Medical Learning Institute Peerview, Miller Medical Communications, North American Center for CME, Physicians’ Education Resource, Rockpointe, and WebMD/Medscape; other activities for Percept and Wiley Blackwell; and stock options from Percept.

SDS reports serving as consultant and/or advisory board member for and receiving honoraria from Abide Therapeutics, Alder, Allergan, Amgen, Avanir, Biohaven, Cefaly, Curelator, Dr. Reddy’s, Egalet, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Health Holdings, eNeura, electroCore, Impel NeuroPharma, Medscape, Novartis, Satsuma, Supernus, Teva, Theranica, and Trigemina.

DK reports serving as consultant for Alder, Amgen, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Nerivio, and Satsuma; and receiving research grants from Alder, Allergan, Amgen, Axsome, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Satsuma, and Teva.

MA reports serving as investigator for Alder, Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva; serving as consultant and investigator for Alder, Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Teva; serving as consultant for Alder and Lundbeck; receiving research grants from Novartis; and other research grants from Lundbeck Foundation and Novo Nordisk Foundation.

UR reports receiving personal compensation from Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Medscape, StreaMedUp, Novartis, and Teva for scientific presentations and participation in advisory board meetings.

DWD reports consulting fees from AEON, Alder, Allergan, Amgen, Amzak Health, Association of Translational Medicine, Autonomic Technologies, Axsome, Biohaven, Charleston Labs, Clexio, Daniel Edelman Inc., Dr Reddy's Laboratories (Promius), ElectroCore, Eli Lilly, eNeura, Equinox, Foresite Capital, Impel, Ipsen, Neurolief, Nocira, Novartis, Oppenheimer, Pieris, PSL Group Services, Revance, Salvia, Satsuma, Sun Pharma (India), Supernus, Teva, Theranica, University Health Network, Upjohn (Division of Pfizer), Vedanta, WL Gore, XoC, Zosano, and ZP Opco; personal fees to develop/deliver educational content for continuing medical education projects from the Academy for Continued Healthcare Learning, Catamount, Chameleon, Global Access Meetings, Global Life Sciences, Global Scientific Communications, Haymarket, HealthLogix, Medicom Worldwide, MedLogix Communications, Mednet, Miller Medical, PeerView, Universal Meeting Management, UpToDate (Elsevier), and WebMD Health/Medscape; personal fees, royalties from Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press, and Wolters Kluwer Health; board of directors, received stock options from Aural Analytics, Epien, Healint, King-Devick Technologies, Matterhorn, Nocira, Ontologics, Precon Health, Second Opinion/Mobile Health, and Theranica; no personal fees or royalties from Allergan for Patent 17189376.1-1466:vTitle: Botulinum Toxin Dosage Regimen for Chronic Migraine Prophylaxis; research funding to institution for salary support from the American Migraine Foundation, Henry Jackson Foundation, PCORI, and US Department of Defense; reimbursement for travel from the American Academy of Neurology, American Brain Foundation, American Headache Society, American Migraine Foundation, Canadian Headache Society, and International Headache Society; personal fees, speaking (not speakers bureau) from Amgen, Lilly, Lundbeck, and Novartis.

FZ, GAR, SC, and DDM are employed by and own stock in Amgen.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by Amgen Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA).

ORCID iD: Stephen D Silberstein https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9467-5567

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017; 390: 1211–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019; 18: 459–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, et al. Chronic migraine in the population: Burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology 2008; 71: 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloudek LM, Stokes M, Buse DC, et al. Cost of healthcare for patients with migraine in five European countries: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). J Headache Pain 2012; 13: 361–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messali A, Sanderson JC, Blumenfeld AM, et al. Direct and indirect costs of chronic and episodic migraine in the United States: A web-based survey. Headache 2016; 56: 306–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serrano D, Lipton RB, Scher AI, et al. Fluctuations in episodic and chronic migraine status over the course of 1 year: Implications for diagnosis, treatment and clinical trial design. J Headache Pain 2017; 18: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, et al. Acute migraine medications and evolution from episodic to chronic migraine: A longitudinal population-based study. Headache 2008; 48: 1157–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katsarava Z, Schneeweiss S, Kurth T, et al. Incidence and predictors for chronicity of headache in patients with episodic migraine. Neurology 2004; 62: 788–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipton RB, Fanning KM, Serrano D, et al. Ineffective acute treatment of episodic migraine is associated with new-onset chronic migraine. Neurology 2015; 84: 688–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manack A, Buse DC, Serrano D, et al. Rates, predictors, and consequences of remission from chronic migraine to episodic migraine. Neurology 2011; 76: 711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scher AI, Buse DC, Fanning KM, et al. Comorbid pain and migraine chronicity: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes study. Neurology 2017; 89: 461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henning V, Katsarava Z, Obermann M, et al. Remission of chronic headache: Rates, potential predictors and the role of medication, follow-up results of the German Headache Consortium (GHC) study. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 551–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi L, Lehto SG, Zhu DX, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of AMG 334, a potent and selective human monoclonal antibody against the calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2016; 356: 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amgen Inc. Aimovig (package insert). Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aimovig (erenumab). Summary of product characteristics. Dublin, Ireland: Novartis Europharm Ltd, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallstrom Y, et al. A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 2123–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet 2018; 392: 2280–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tepper S, Ashina M, Reuter U, et al. Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakai F, Takeshima T, Tatsuoka Y, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of erenumab for the prevention of episodic migraine in Japanese adults. Headache 2019; 59: 1731–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarchielli P, Romoli M, Corbelli I, et al. Stopping onabotulinum treatment after the first two cycles might not be justified: Results of a real-life monocentric prospective study in chronic migraine. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, et al. Per cent of patients with chronic migraine who responded per onabotulinumtoxinA treatment cycle: PREEMPT. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86: 996–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipton RB, Cohen JM, Yang R, et al. Long-term efficacy of fremanezumab in patients who reverted from a chronic to an episodic migraine classification. Headache 2019; 59(Suppl1): 101–102.

- 25.Hindiyeh NA, Detke HC, Day K, et al. Shift from chronic migraine to episodic migraine status in a long-term phase 3 study of galcanezumab. Headache 2019; 59(Suppl1): 103.

- 26.Han L, Liu Y, Xiong H, et al. CGRP monoclonal antibody for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: An update of meta-analysis. Brain Behav 2019; 9: e01215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silberstein S, Tfelt-Hansen P, Dodick DW, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 484–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashina M, Dodick D, Goadsby PJ, et al. Erenumab (AMG 334) in episodic migraine: Interim analysis of an ongoing open-label study. Neurology 2017; 89: 1237–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]