Graphical abstract

Keywords: Polyacrylonitrile, TiO2, Graphene oxide, Ultrasonic, Dye degradation

Highlights

-

•

PAN/β-cyclodextrin membranes were prepared by electrospinning.

-

•

TiO2/graphene oxide were deposited by ultrasonic-assisted electrospray.

-

•

The composite membranes displayed good antibacterial and photocatalytic properties.

-

•

The degradation efficiency for dye remained above 80% after 3 cycles.

-

•

The photodegradation mechanism of the membrane was examined.

Abstract

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN)/β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) composite nanofibrous membranes immobilized with nano-titanium dioxide (TiO2) and graphene oxide (GO) were prepared by electrospinning and ultrasonic-assisted electrospinning. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed that TiO2 and GO were more evenly dispersed on the surface and inside of the nanofibers after 45 min of ultrasonic treatment. Adding TiO2 and GO reduced the fiber diameter; the minimum fiber diameter was 84.66 ± 40.58 nm when the mass ratio of TiO2-to-GO was 8:2 (PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membranes was 191.10 ± 45.66 nm). Using the anionic dye methyl orange (MO) and the cationic dye methylene blue (MB) as pollutant models, the photocatalytic activity of the nanofibrous membrane under natural sunlight was evaluated. It was found that PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membrane with an 8:2 mass ratio of TiO2-to-GO exhibited the best degradation efficiency for the dyes. The degradation efficiency for MB and MO were 93.52 ± 1.83% and 90.92 ± 1.52%, respectively. Meanwhile, the PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membrane also displayed good antibacterial properties and the degradation efficiency for MB and MO remained above 80% after 3 cycles. In general, the PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membrane is eco-friendly, reusable, and has great potential for the removal of dyes from industrial wastewaters.

1. Introduction

Water is one of the most vital resources necessary for human survival and development. In recent years, because of rapid population growth, urbanization, and industrialization, water pollution has become increasingly serious. Methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO) are the major water pollutants due to the highly carcinogenic and toxic properties that may cause serious health problems [1]. Pathogenic microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses, and others) present in polluted water is another thorny problem and one of the most deadly threats to human health [2]. Therefore, it is imperative to use effective methods to remove toxic synthetic dyes and microorganisms from aqueous environments.

Adsorption is a commonly used method to remove pollutants from water because of its advantages of low cost, simple operation, remarkable results and no byproducts [3]. Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) has become a commonly used material in water treatment due to its excellent mechanical stability, thermal stability, and chemical resistance. Electrospun PAN nanofibers range in size from tens to hundreds of nanometers, giving them great application potential in the adsorption of organic dyes because of their higher surface to volume ratio and high surface area [4]. PAN nanofibrous membranes have a tendency to plasticize and swell in aqueous environments, however, and they have a limited ability to adsorb pollutants. Therefore, PAN is often combined with other materials. β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) is considered to be an excellent adsorbent due to its special hydrophobic cavity and hydrophilic outer wall structure [5]. Due to its low solubility in water, good intramolecular hydrogen bond positioning, higher complexation ability, stable crystal structure and low cost, β-CD is the first choice for environmental research material [6]. Abd-Elhamid et al. prepared PAN/β-CD/graphene oxide composite nanofibrous membranes by electrospinning, achieving a removal rate of up to 90% for crystal violet (CV) dyes [7]. In addition, β-CD exhibits an outstanding performance on entrapping and enriching various inorganic, organic, and biological guest molecules near reactive oxygen species (ROS) -generating sites, facilitating photocatalytic process [8]. Moreover, β-CD also plays an important role in photogenerated charge transfer, because it can be used as a hole scavenger to inhibit the recombination of electron-hole pairs, previous studies have proved that β-CD is capable of improving electron transfer on the TiO2 surface and enhancing adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of pollutants on the TiO2 surface [9]. Good adsorption performance can provide a favorable condition for the subsequent photocatalytic degradation. As reported by Wu et al., the dye molecules are first adsorbed on the surface of the porous nanofiber, and then migrate to the photocatalyst (TiO2) and degrade by photocatalysis under UV irradiation [10].

Photocatalytic degradation is another effective method for removing organic dyes from wastewater. Anatase-type TiO2 is one of the most widely investigated photocatalytic materials due to its photostability, strong oxidation ability, low cost, and relative non-toxicity [11]. Fathinia et al. studied the effect of immobilized TiO2 nanoparticles on the removal of phenazopyridine under different oxidation processes, and found that the use of ozonation photocatalysis can obtain the highest phenazopyridine removal efficiency (85% at 35 min) [12]. However, the photoinduced electron-hole recombination in TiO2 easily facilitates rapid recombination, which greatly reduces the photocatalytic efficiency [13]. Carbon nanomaterials can provide electron carriers and electron transmission channels for TiO2, thereby greatly improving the photocatalytic efficiency of [3]. For example, graphene oxide (GO) can act as an electron carrier in composites with enhanced catalytic properties, and the limitations of the latter can be reduced by combining it with TiO2 [14]. In addition, although nanoscale photocatalysts can effectively decompose a lot of organic pollutants, there are usually two problems with the powdered form: in practical applications, it may seriously reduce the photocatalytic activity due to instability and aggregation [15]; moreover, the powdered catalyst is difficult to recycle, and its residue may cause potential cytotoxicity and secondary pollution [16]. Compared with traditional supports, PAN-based nanofibers have the following advantages: (i) During use and operation, TiO2-GO nanoparticles (NPs) are embedded into the nanofibers to completely avoid the secondary pollution caused by the peeling away of TiO2-GO NPs from the nanofibers [17]; (ii) the electrospun PAN nanofibers readily float on water because of their low density and hydrophobicity, thus promotes the penetration of light [13]; and (iii) the high porosity and specific surface area of nanofibers provide effective contact between photocatalysts and pollutants. Previous research has revealed, however, that it is difficult to obtain a homogeneous distribution of TiO2 NPs on GO in composite materials by overcoming the agglomeration among the nanostructures [18]. Nanostructures tend to accumulate along the wrinkles or other defects of GO sheets rather than disperse evenly on GO. This agglomeration decreases the separation of photogenerated charge carriers across the interface, thereby reducing the synergistic catalytic between GO and TiO2 [18]. It is well known that ultrasonic treatment is an effective method for dispersing nanoparticles. During ultrasonic treatment, the NPs are depolymerized from large aggregates into small dispersions due to the large amount of energy generated by the cavitation effect (i.e., the rapid formation, growth, and breakdown of unstable bubbles in the liquid), and the specific surface area of nanomaterials is increased so as to perform its role effectively [19]. Baig et al. found that TiO2 NPs can be well dispersed and uniformly attached to the surface of GO sheets under ultrasonic conditions. This method increases the interaction between NPs and GO sheets, resulting in a larger surface area, further promoting adsorption and photocatalysis [20]. Jamal Sisi et al. reported that a new combination of ZIF-8 nanomaterials and sonolysis process was used to effectively activate potassium peroxydisulfate, thereby establishing a new sonic-assisted indirect photocatalytic combination process, and the sonocatalysis process can successfully improve the overall ecotoxicity reduction of acid blue 7 in 90 min [21].

Based on the above analysis, we prepared a porous PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membrane through the use of electrospinning technology combined with ultrasonic-assisted electrospray deposition, which exhibits better adsorption, photocatalysis, recyclability, and antibacterial properties. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were used to study the structure and morphology of the composite nanofibrous membranes. In addition, using the cationic dye MB and the anionic dye MO as models, the removal effect of the composite nanofibrous membrane under natural light exposure of the dye was evaluated. Meanwhile, the recyclability and photodegradation mechanism of the composite nanofibrous membrane were examined as well. Finally, the antibacterial properties of the composite nanofibrous membrane were also studied.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN, Mn = 150,000, density: 1.14 g/cm3, relative density: 1.12) was purchased from Huachuang Pastic Co., Ltd., Dongguan, China. β-cyclodextrin (β-CD, density: 1.23 g/cm3) was procured from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Multilayer graphene oxide (GO, carbon content < 50 wt%, oxygen content > 42 wt%, sulfur content < 4 wt%, lamellar diameter: 10–50 μm, 1 or 2 layers and purity > 95%) was procured from Carboniferous Graphene Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China. TiO2 NPs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (particle size: 10 nm).

2.2. Preparation of PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membranes

TiO2 NPs + GO (total mass: 5% of mPAN+β-CD) was added to N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) according to the mass ratios of 10:0, 9:1, 8:2, 7:3, 6:4, 5:5, and 0:10 [20] and ultrasonicated for 1 h (frequency: 40 kHz, power: 120 W, temperature: 40 °C) using a KS-200 T ultrasonic instrument (Shanghai Keqi Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) equipped with a reactor with a thermostatic water bath (temperature accuracy of ± 1 °C). Then, A portion of the PAN and β-CD was added and stirred until dissolved completely at 40 °C (to guarantee that the mass fraction of PAN/β-CD was 10%, the PAN and β-CD ratio was 8:2) to obtain a mixed solution [7]. In order to prepare the porous nanofibrous membranes, 5 wt% glycerol was added to the mixed solution and the stirring was continued until the solution was completely mixed, thereby obtaining the spinning solution [10]. In order to investigate the effect of sonication on membrane performance, this solution was aliquoted into 5 portions and an ultrasonic liquid processor was used to sonicate for 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min to obtain the final PAN/β-CD spinning solution. Finally, a 10-mL syringe containing the electrospinning precursor solution was connected to a flat metal needle with a diameter of 0.7 mm. The needle was fixed to the holder and perpendicular to the collecting plate. The DC voltage was set to 18 kV, the flow rate to 0.4 cm/h, and the receiving distance to 18–20 cm for electrospinning. After electrospinning, the nanofibers were vacuum-dried at room temperature for 24 h prior to further use.

2.3. Morphological characterization

One part of a nanofibrous membrane was cut crosswise, the FEI Quanta 200 FEG SEM (FEI Co., Hillsboro, OR, USA) was used to perform SEM analysis on the surface and cross sections of nanofibrous membranes that had been ultrasonicated for 45 min. The acceleration voltage was 10 kV and the conductive gold was pre-coated on the nanofibrous membrane surface using a sputter coater prior to observation. The fiber diameter distribution of the nanofibrous membranes was determined by image analysis using Image J software. In order to prove the existence of TiO2 NPs and GO, EDS mapping was performed on the composite nanofibrous membranes. TEM (Tecnai G2 F20 S-Twin, FEI Co.) was used to detect the distribution of TiO2 NPs and GO components in the PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed using a Nicolet IS10 spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet Corp.) with a resolution ratio of 4 cm−1, a scan time of 32 s−1, and a measurement range of 4000–650 cm−1. The crystal structures of the TiO2 NPs, GO, and nanofibrous membranes were measured using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, MPX3, MAC Science, Japan) with nickel-filtered Cu Kα radiation, 40-kV voltage, and 30 mA current. Scattered radiation was detected in the angular range 2θ = 5–80° with a 0.02° step size. The porosity and pore size of the porous nanofibrous membranes were measured according to the method of Hosseini et al. [22].

2.4. Differential scanning calorimetric properties

Dynamic experiments were performed using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC, Q200 V24.2 Build 107, USA) in a nitrogen atmosphere (50 mL min−1). Approximately 5 mg of each nanofibrous membrane was sealed in an aluminum pan and heated from 20 to 400 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1.

2.5. Water barrier properties and mechanical properties

The water vapor permeability (WVP) test was performed according to ASTM method E96 (1996) [23]. And the mechanical properties were determined using a tensile tester (HDB609B-S, Haida International Equipment Co., Ltd.) with appropriate data processing software according to ASTM standard method D882-101 [24]. The nanofibrous membranes were cut into dimensions of 10 mm × 60 mm and their thickness was measured. The test was carried out at the room temperature and a moving crosshead speed of 5 mm/s. At least 10 tests were performed on each nanofibrous membrane composition.

2.6. Swelling and water solubility

The swelling (Sw) and water solubility (WS) were determined according to a slightly modified version of Sun et al.’s method [25]. The nanofibrous membranes were cut into 3 cm × 3 cm pieces and dried at 105 °C to a constant weight in order to obtain mass M1. They were then placed in a petri dish containing 50 mL of distilled water and stored at 25 °C for 24 h. Next, the moisture was wiped off the wet nanofibrous membranes using dry filter paper and they were weighed in order to obtain mass M2, and finally dried to a constant weight at 105 °C to obtain M3. The water solubility and swelling were calculated as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

2.7. Photocatalytic dye degradation studies

The photocatalytic activities of different nanofibrous membranes were investigated in terms of the degradation of the cationic dye MB and the anionic dye MO using 10–100 mg/L aqueous dye solution [22], [27]. For each sample, 20 mg nanofibrous membrane was immersed in MB or MO solution (10 mg/L, 100 mL). The mixed solutions were magnetically stirred for 60 min under dark conditions to achieve adsorption–desorption equilibrium. Next, 10 mL of the MB or MO solutions were centrifuged, and the absorbance of the supernatant at 664 or 463 nm was then measured, and the initial concentration calculated (Ci) using the standard curves of MB and MO. The solution was then illuminated at a given time interval (to study the photocatalytic degradation of the dye under natural light), and the absorbance of the solution was measured. All photodegradation experiments were carried out 3 times and the average value was utilized. The photocatalytic degradation efficiency of the MB and MO dyes was calculated using the following formula:

| (3) |

where is the dye concentration after a particular irradiation time.

2.8. Regeneration and reusability

In order to examine the photochemical stability of the PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes cycle tests were performed. In each cycle, the nanofibers were separated from the organic dyes, washed with distilled water, and dried at 60 °C for 24 h. Five consecutive photodegradation cycles were performed using the same experimental method under UV light photocatalytic conditions (closed chamber (0.6 × 0.4 × 0.3 m3) equipped with 2 mercury lamps of 8 W UV-A (315–380 nm)) to determine reusability [13].

2.9. Antimicrobial properties

The Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method was used to determine the antimicrobial activity of the nanofibrous membranes against Escherichia coli (E. coli, ATCC9677) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, ATCC 27853) [28]. Membrane samples (disks with a diameter of 8 mm, exposed to UV light for 24 h) were placed in the center of inoculated agar (containing approximately 108 CFU/mL of E. coli or S. aureus), and the plates were inoculated at 37 °C for 24 h. The diameter of the inhibition zone was measured to the nearest millimeter, and the inhibition zone around each sample was calculated and used to represent the antibacterial property of the membranes.

2.10. Statistical analysis

The final result was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The SPSS 24.0 statistical analysis system was used for analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multi-range teats were used for significantly different from the other groups (p < 0.05).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Morphology characterizations

As can be seen from the optical images of the nanofiber membrane (Fig. 1 (a1)–(h1)), the surfaces of the nanofibrous membranes were flat and smooth, and the color continued to deepen as the GO content increased. The SEM images of the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membranes and composite nanofibrous membranes with different TiO2-to-GO mass ratios are shown in Fig. 1 (a2)–(h2), the corresponding magnified images are shown in Fig. 1 (a3)–(h3), sectional cut image of nanofibrous membrane (TiO2:GO = 8:2) is shown in Fig. 1(d5) and the histogram of the diameter distribution of the nanofibers is shown in Fig. 1 (a4)–(h4). It can be seen that all of the fibrous membranes exhibited nanofibers with random orientation and rough porous surface structure. Interestingly, the uniform convexity and porous structure of the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous surface observed in this experiment may be due to the addition of 5 wt% plasticizer glycerol to the spinning solution [29], which increased the viscosity and surface tension of the electrospinning solution, and the glycerol in the spinning solution hindered the evaporation of DMF during electrospinning. Therefore, in the region of the electrospun nanojet, rapid phase separation occurred between the PAN/β-CD and DMF, thus forming rough surfaces and nanopores in the nanofibers. It can be further explained by the typical phase diagram of the polymer-solvent-non-solvent ternary system (Fig. 2a). When both DMF and glycerin are present in the system, the initial composition of the PAN/β-CD solution is in the uniform region I of the phase diagram. During the electrospinning process, the PAN/β-CD solution will enter the liquid-liquid demixing region II and separate as a polymer-rich phase and a polymer-poor phase with the evaporation of DMF and glycerol. As the electrospinning progresses, the distance between the initial concentration point and the binodal demixing curve decreases, and the composition of the solution approaches the “cloud point” of the ternary system, indicated that strong phase separation is more likely to occur. The composition of the PAN/β-CD solution may pass through the phase boundary during the electrospinning process and enter the region III in a relatively short time, which will lead to an interconnected porous structure, a feature of spinodal decomposition phase separation [30]. The porous structure of the nanofibrous membrane can further increase the specific surface area of the fiber, and improve the adsorption and photocatalysis. Feng et al. [17] and Prahsarn et al. [10] found similar results for PAN fibers with added water.

Fig. 1.

optical images (a1-h1), typical SEM (b2-h2) 100000x, (c3-h3) FESEM images of the different composite nanofibrous membranes (ultrasound time, 45 min) and (d4-h4) nanofiber diameter distribution histogram of different composite nanofibrous membranes, (d5) sectional image of nanofibrous membranes (TiO2:GO = 8:2). The nanoparticle distributions with corresponding standard deviations (SD) are shown as insets.

Fig. 2.

(a) A typical phase diagram of a ternary system: polymer (P)-solvent (S)-nonsolvent (NS). I. Stable region. II. Metastable region, liquid–liquid demixing region. III. Unstable region, solid–liquid demixing region and (b) Porosity and mean pore radius of different nanofibrous membranes (ultrasound time, 45 min).

After adding TiO2 NPs and GO, the roughness of the composite nanofibrous membrane was further increased, and the TiO2 NPs and GO were randomly distributed on the surface or inside of the nanofiber. It can be seen in Fig. 1 (b2)–(h2) and (b3)–(h3) that some small bumps appeared on the nanofibers, which correspond to the agglomerates of the TiO2 NPs [31]. The agglomeration of the TiO2 NPs are clearly visible in the PAN/β-CD/TiO2 nanofibrous membrane (317.90 ± 57.47 nm) attached to the surface of the nanofiber. With the increase of GO content, the aggregate size of the TiO2 NPs in the composite nanofibers decreased significantly (from 187.07 ± 41.77 to 32.00 ± 10.23 nm), possibly because GO can combine with metal oxide TiO2 NPs, thereby reducing the aggregation effect and producing smaller aggregates [32]. In the PAN/β-CD/GO nanofibrous membrane shown in Fig. 1 (h2), larger GO sheets appeared, and since the GO content was high, the dispersion of the GO sheets diminished and they tended to aggregate during the electrospinning process, which led to an increase in roughness and sheet formation. The observed clusters of NPs after ultrasonic treatment revealed that the NPs were not dispersed in the form of single peak, but in the form of aggregates, which was consistent with the research results of Estrada-Monje et al. [19]. With the exception of the PAN/β-CD/TiO2 nanofibrous membrane, the TiO2 NPs were evenly distributed between the nanofibers and within the nanofibers, without any serious agglomeration or significant changes in structure. Untreated TiO2 NPs easily to agglomerated due to their high surface energy [33].

3.2. Diameter distribution of nanofibers

Fig. 1 (a4)–(h4) present the histograms of the diameter distributions of these nanofibers. It can be seen that they were mainly distributed in the range of 84.66 ± 40.58–191.10 ± 45.66 nm. Compared with PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membranes (191.10 ± 45.66 nm), the diameter of the nanofibers exhibited a downward trend after the addition of TiO2 NPs and GO (84.66 ± 40.58 nm – 121.25 ± 52.79 nm) (p < 0.05). This is due to the fact that adding the TiO2 NPs and GO to the PAN/β-CD solution increased the conductivity [32]. It can be seen from Table 1 that the conductivity of the solution is significantly increased after adding nanofillers (p < 0.05), PAN/β-CD conductivity was 57.27 ± 0.88 μS/cm, and the conductivity of the mixed solutions were in the range of 60.23 ± 0.98 μS/cm to 112.8 ± 0.26 μS/cm, the increase of the conductivity made the charge density of the droplet formed at the needle tip increase. Therefore, the sprayed jet had a stronger elongation force in the electric field and formed finer composite nanofibers at the same electrospinning conditions [29], [34]. In general, as the GO content increased, the diameter of the nanofibers displayed an increasing trend, although the results were not significantly different (p > 0.05). This may be due to the fact that although the conductivity continued to increase with the increase of the conductive GO content, GO was a micro-sized nanosheet, and the nanofiber was easily swollen by the GO sheets [7]. Therefore, although under the electrical conductivity of large its diameter compared low GO content was increased, and the diameter of the composite nanofibers was the smallest (84.66 ± 40.58 nm) when the TiO2-to-GO mass ratio was 8:2.

Table 1.

Electrical conductivity of PAN/β-CD solutions with different mass ratio of TiO2-to-GO (ultrasound time, 45 min).

| Samples | Electrical conductivity (μS/cm) |

|---|---|

| PAN/β-CD | 57.27 ± 0.88g |

| 10:0 | 60.23 ± 0.98f |

| 9:1 | 66.30 ± 0.28e |

| 8:2 | 68.13 ± 0.21e |

| 7:3 | 73.65 ± 0.74d |

| 6:4 | 84.50 ± 0.90c |

| 5:5 | 89.38 ± 1.20b |

| 0:10 | 112.80 ± 0.26a |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.3. Porosity and pore size analysis

The porosity and pore size of different nanofibrous membranes are shown in Fig. 2. The porosity of the nanofibrous membranes ranged from 82.03 ± 1.51% to 84.50 ± 1.52%. Adding nanofillers can slightly increase the porosity of nanofibrous membranes, but there was no significant difference among the nanofibrous membranes (p > 0.05). The pore size of the composite nanofibers decreased significantly after the addition of nanofillers (p < 0.05). The minimum pore size was 742.47 ± 85.94 nm when the TiO2-to-GO mass ratio was 8:2, which was 55.70% lower than that of the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membranes (1675.95 ± 135.63 nm). This is mainly because the pore size depends on the average fiber diameter, and there is a parallel relationship between the pore size and the average fiber diameter. In addition, porosity also has an effect on pore size, but fiber diameter is the dominant variable controlling membrane pore size [35]. As we all know, high specific surface area, high porosity, and smaller pore size among nanofibers can provide more adsorption sites. TiO2 NPs and GO have a high adsorption capacity and further increased the specific surface area of the nanofiller by electrospinning, providing higher porosity and smaller pore size, thereby improving the adsorption efficiency [1].

3.4. EDS analysis

In order to further determine whether the TiO2 NPs and GO were present in the composite nanofibers, the element distributions of the fiber membranes (TiO2-to-GO mass ratio of 8:2) were examined using EDS. It can be proven from Fig. 3 (a)–(e) that the C, O, and Ti elements were evenly distributed in the porous PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane, indicating that the TiO2 NPs and GO were evenly dispersed in the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membranes without aggregation, indicating that ultrasonic treatment can effectively improve the dispersion of nanomaterials. The EDS results confirmed the embedding of TiO2 NPs and GO in the PAN/β-CD matrix.

Fig. 3.

Typical EDS (a-d) images of the PAN/β-CD/GO/TiO2composite nanofibrous membrane (TiO2:GO = 8:2, ultrasonication time, 45 min) and (e) EDS spectra and elements.

3.5. TEM analysis

To observe the microstructure and encapsulation of TiO2 NPs and GO in the PAN/β-CD matrix, TEM studies were performed. Fig. 4 (a1)–(a4) are the TEM images of the PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membrane without ultrasonic treatment (TiO2-to-GO mass ratio of 7:3), and Fig. 4 (b1)–(b4) are the TEM images after ultrasonic treatment for 45 min. TiO2 and GO are clearly visible in Fig. 4. TiO2 mainly existed on the surface and inside of the nanofiber, while GO displayed a smooth and thin wrinkled layer of different transparency within the nanofiber. It is readily apparent from Fig. 4 (a2) and (a3) that in the composite nanofibrous membrane, the partially exfoliated GO sheets were encapsulated with TiO2 NPs, which may be due to the local heterojunction between the GO and TiO2 NPs. This was consistent with the results of Jhaveri et al. [36]. By comparing Fig. 4 (a1)–(a4) and (b1)–(b4), it can be seen that ultrasonic treatment can effectively promote the dispersion of nanofillers in the PAN/β-CD matrix. The nanofillers in the composite nanofibers without ultrasonic treatment existed in the form of large agglomerates and were unevenly distributed; after 45 min of ultrasonication, however, the nanofillers were uniformly dispersed on the surface and inside of the nanofibers, and the size of the agglomerates decreased significantly. It has been reported that NPs after ultrasound are not dispersed in a singlet state, but in an aggregated state [23]. This is mainly due to the kinetic and thermal energy generated by ultrasonic cavitation acting on large agglomerates to promote their dispersion into smaller agglomerates, making them more evenly distributed in the nanofiber [37]. The diameter of the nanofibrous membrane after ultrasonic treatment (219.55 ± 20.42 nm) was significantly smaller than the diameter without ultrasonic treatment (403.21 ± 45.40 nm). This is mainly due to the decrease in the viscosity and the increase in conductivity of the spinning solution after ultrasonic treatment. The increasing of solution conductivity can increase the surface charge of the polymer jet, which significantly promotes the stretching of the polymer jet during the flight to the collection plate, resulting in a reduction in nanofiber diameter [38]. In addition, Fig. 4 (b3) and (b4) reveal that the incorporated TiO2 NPs were mainly columnar in shape, with an average length of 23.87 ± 3.47 nm and an average diameter of 10.23 ± 2.04 nm.

Fig. 4.

Typical TEM images of the composite nanofibrous membranes (TiO2: GO = 8:2, (a1-a4) without ultrasonic treatment, (b1-b4) ultrasonic treatment for 45 min.

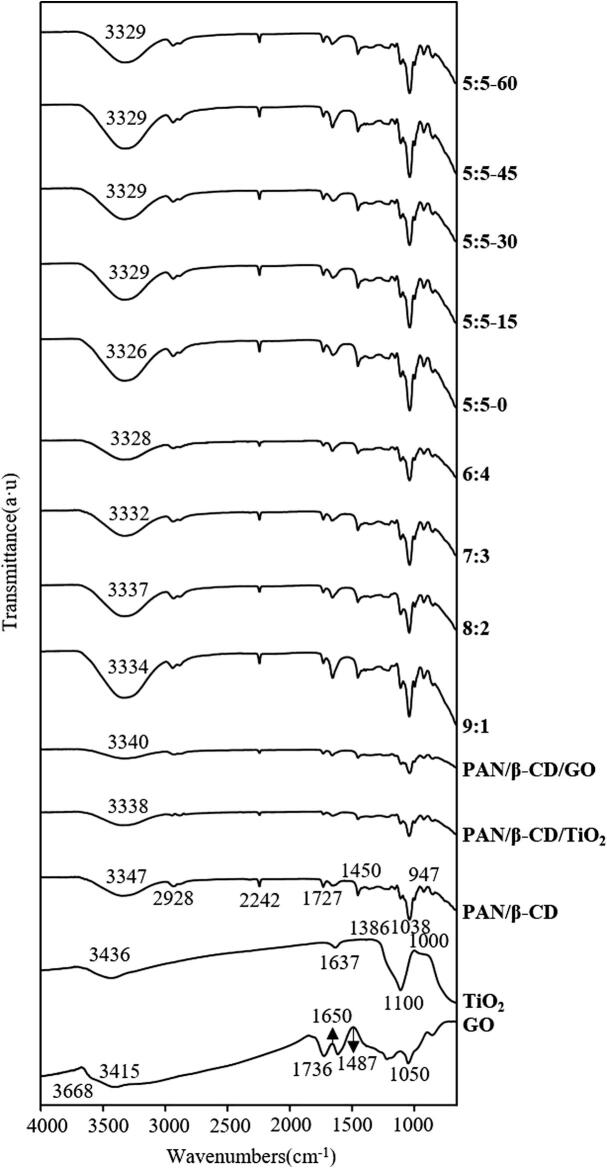

3.6. FTIR analysis

The FTIR spectra are presented in Fig. 5. The broad band at 650–1000 cm−1 belongs to the Ti-O-Ti stretching, and the peak around 1110 cm−1 may correspond to the Ti-OH stretching vibration [39]. The absorption peaks around 1386 cm−1 and 1637 cm−1 can be attributed to the characteristic peak of O—O groups and the characteristics peak of water, respectively. The peak around 3436 cm−1 was due to the presence of moisture on the surface of the TiO2 and the stretching vibration of the hydrogen bond O—H [40]. In the GO spectrum, the peak around 3668 cm−1 can be ascribed to the adsorption of water molecules. In addition, there were 4 characteristic peaks at 3415, 1736, 1650, and 1487 cm−1, which were attributed to O—H stretching vibration, C O stretching vibrations of carboxyl groups, in-plane stretching of the sp2-hybrid C C skeleton [41], and the carboxyl C—O stretching mode, respectively [42]. The PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane displayed characteristic vibrations at 2928 cm−1 for —CH2 stretching, 2242 cm−1 for C N stretching, and 1450 cm−1 for —CH2 bending, corresponding to the characteristic peaks of PAN [43]. The intense and broad band at 3347 cm−1 in the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane was caused by the O—H stretching vibration of hydroxyl groups. The adsorption band at 1727 cm−1 was due to the C O stretching vibration of the carboxyl groups and ester groups [8]. The spectra of the PAN/β-CD/GO and PAN/β-CD/TiO2 nanofibrous membranes were similar to the spectrum of the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane, with a slight decrease in intensity. When TiO2 NPs and GO were added, the spectrum of the composite nanofibrous membrane was also similar to that of the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane, although the peak intensity was significantly enhanced. As the proportion of TiO2 NP in the nanofibrous membrane gradually decreased, the peak intensity decreased somewhat, but no new peak appeared, indicating that TiO2 NPs and GO only physically interacted with the PAN/β-CD matrix (such as van der Waals force and hydrogen bonding). Ultrasonic treatment did not change the overall morphology of the FTIR spectrum, and the effect of ultrasound on infrared was mainly reflected in the peak intensity and wave number shift [44]. It was found that the peak intensity of the composite film first weakened and then strengthened, although it was lower overall than that of the composite film without ultrasonic treatment. This may be due to the cavitation of ultrasonic waves, which makes the TiO2 NPs and GO more uniformly dispersed, and strengthens the physical combination of the 2 NPs with the PAN/β-CD matrix. Hence, the characteristic peaks belonging to PAN/β-CD in the composite nanofibrous membrane were weakened.

Fig. 5.

FTIR spectra of GO, TiO2 NPs, PAN/β-CD, PAN/β-CD/GO, PAN/β-CD/TiO2 and different PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membrane (not processed with ultrasonication), and typical PAN/CD/GO/TiO2 composite nanofibrous membranes (TiO2:GO = 5:5) under different ultrasound times.

3.7. XRD analysis

The diffraction peaks of the TiO2 NPs at 2θ = 25.44°, 37.95°, 48.26°, 54.03°, 62.85°, 69.01°, 70.46°, and 75.26° corresponded to the crystal planes of (1 0 1), (1 0 3), (1 0 1), (0 0 4), (2 0 0), (1 0 5), (2 1 1), (2 0 4), (1 1 6), (2 0 0), and (2 1 5), respectively, confirming the pure tetragonal anatase phase of TiO2 (JCPDS No. 21-1272) (Fig. 6) [45]. The anatase TiO2 NPs exhibited excellent photocatalytic and antibacterial properties. GO displayed a sharp absorption peak at 2θ = 9.88°, which was related to the (0 0 1) crystal plane of GO [9]. Based on the interlamellar spacing formula λ = 2dsinθ, the spacing was calculated to be ~0.82 nm. Compared with the graphite interlamellar spacing (0.44 nm), due to the introduction of —COOH and —OH polar functional groups during the oxidation of the atomic layer, the interlayer spacing of GO was greatly increased, resulting in the GO layer not being as flat as the graphene conjugate layer and expanding the layer spacing, thus providing favorable conditions for the photodegradation reaction of TiO2-GO complexes. In addition, according to Hernández-Majalca et al., the diffraction peak at 2θ = 44° may be related to the crystal plane (1 0 0) of grapheme [42]. The XRD patterns of the PAN/β-CD porous nanofibrous membranes exhibited typical diffraction peaks at 2θ = 16.98° and 26.74°, corresponding to the (1 1 0) and (0 0 2) crystal planes of PAN, respectively, where the 2θ = 16.98° diffraction peak indicated orthorhombic packing, which is formed by the stretching of the polymer chain during spinning. The sharp absorption peaks at 2θ = 10.92°, 12.54°, 17.54°, 18.66°, 19.8°, 20.72°, and 22.64° corresponded to the characteristic diffraction peaks of β-CD, thus indicating the crystalline nature of β-CD. These findings are consistent with the results of Lou et al. [47]. This further revealed that PAN and β-CD were only physically mixed, so that the β-CD cavity was retained, which was beneficial to the adsorption experiment. The broad peak observed in the PAN/β-CD/GO porous nanofibrous membranes from 14.3 to 31.56° was mainly due to the amorphous nature of PAN. The characteristic peaks of GO were not evident, however, and the diffraction peaks related to β-CD had mostly disappeared. The intensity of the characteristic peaks corresponding to β-CD at 2θ = 12.42° and 17.52° weakened, which may be due to the destruction of the ordered and layered GO structure during the mixing and ultrasound process, and the GO was evenly dispersed in the nanofibers [17]. The XRD patterns of the PAN/β-CD/TiO2 and PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO porous nanofibrous membranes exhibited the characteristic peaks of TiO2 at 25.22° and 48.00°, although the intensity of these peaks was significantly lower, indicating that TiO2 was successfully embedded in the PAN/β-CD matrix. It was worth noting that the strong and sharp peaks of anatase TiO2 in the nanofibrous membrane at 25.22° showed good crystallinity in the membrane, and these peaks became more intense as the concentration of TiO2 NPs increased [45]. In addition, the characteristic peaks of the TiO2 NPs displayed a tendency to shift to a low angle in the nanofibrous membrane, which may be due to the strong hydrogen bonding between the TiO2 NPs and PAN/β-CD, which changed the crystal structure of the composite nanofibrous membrane and affected its structural performance.

Fig. 6.

XRD patterns of GO, TiO2 NPs, PAN/β-CD, PAN/β-CD/TiO2, PAN/β-CD/GOand typical PAN/β-CD/GO/TiO2 composite nanofibrous membranes (GO: TiO2 NPs = 5:5, not processed with ultrasonication).

3.8. DSC analysis

As shown in Fig. 7a, DSC was measured to analyze the thermal properties of porous nanofibrous membranes. The glass transition temperature (Tg) is the temperature at which the polymer relaxes when the material changes from an amorphous solid state (glass state) to a more viscous rubber state. The higher the Tg, the greater the barrier property of the polymer [48]. After the addition of nanofillers, the Tg of each composite nanofibrous membrane increased, which was mainly caused by the restricted mobility of the PAN/β-CD polymer chains. Because of the ability of TiO2 NPs to form chemical bonds on the hydroxyl sites provided by the PAN/β-CD and GO layers, which can greatly slow the segmentation dynamics of the PAN/β-CD chains in the vicinity of the surface. The possible crowding and/or local ordering of the chains at the interface and the loss of configuration entropy of the PAN/β-CD fragments near the surface of the nanomaterial reduce the chain mobility, which is also reflected in the change of Tg. Alternatively, the strong interaction between PAN/β-CD and nanofillers may also slow down the movement and melting of the polymer chains during heating [49]. Oleyaei et al. [50] reported that the increased Tg in starch/TiO2 nanocomposites was because of the hydrogen bond formed by TiO2 NPs and starch that hindered the movement of strach chains. Oleyaei et al. [49] also found that after the addition of montmorillonite (MMT) and TiO2 NPs, the diffusion of starch chains into the interlayer space of MMT nanosheets hindered the movement of chains because of the chemical interaction between nanofillers and starch. It is worth noting that the Tg of the nanofibrous membrane after the addition of GO (91.17 and 104.60 °C) was significantly higher than that of the nanofibrous membrane to which only TiO2 NPs had been added (84.42 °C). This was mainly the result of the barrier properties of GO. Compared with other nanofillers, GO nanosheets have a very large surface area and aspect ratio, which can effectively improve the barrier properties of polymers and improve the thermal stability of composite nanofibrous membranes [51].

Fig. 7.

(a) DSC thermograms of PAN/β-CD, PAN/β-CD/TiO2, PAN/ β-CD/GO and PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO (TiO2:GO = 5:5) and (b) Free-radical cyclization reaction initiated by H•.

The DSC curve of the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane exhibited a broad exothermic peak at 302.85 °C, corresponding to the cyclization reaction of PAN homopolymer by the free radical mechanism (Fig. 7b) [52]. It is known that the large amount of exothermic heat generated by the cyclization reaction can cause the PAN molecular chains to break, and subsequently cause defects in the carbon fiber. After adding TiO2 NPs, the composite nanofibrous membrane displayed a short and broad exothermic peak at 265.66 °C, and the corresponding cyclization reaction temperature and total exothermic temperature were reduced. This is mainly because of the existence of TiO2 NPs on the surface and inside of the nanofibers (confirmed by the SEM and TEM results), from which the functional groups introduced by the NPs initiated the cyclization reaction at low temperature through an additional ionic mechanism. The PAN/β-CD/GO composite nanofibrous membrane showed a strong and sharp exothermic peak caused by the cyclization reaction at 308.59 °C. Compared with the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane, the exothermic temperature increased by 6 °C and the reduced heat release indicated that the addition of GO hindered the cyclization reaction of PAN, which may be due to the better dispersion of GO in the PAN/β-CD matrix after ultrasonic peeling [53]. The corresponding cyclization temperature in the PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membrane was 284.54 °C, which was between the temperatures of the PAN/β-CD and PAN/β-CD/TiO2 nanofibrous membranes, and significantly lower than that of the PAN/β-CD/GO nanofibrous membrane, indicating that TiO2 played a leading role in the quaternary nanofibrous membrane.

3.9. Swelling, water solubility, and water vapor permeability

Table 2 shows the Sw, WS, and WVP of the different nanofibrous membranes. The Sw, WS, and WVP of the composite nanofibrous membranes loaded with TiO2 NPs and GO were significantly lower than that of the pure PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane (p < 0.05). When the TiO2-to-GO mass ratio was 8:2, the Sw, WS, and WVP of the composite nanofibrous membrane reached the minimum values of 198.18 ± 13.39%, 13.69 ± 1.25%, and 1.33 ± 0.12 × 10-10 g·pa-1s-1m−1, respectively, which were 31.11%, 42.70%, and 58.18% lower than the corresponding values of the pure PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane (287.67 ± 19.58%, 23.89 ± 3.47%, and 3.18 ± 0.39 × 10-10 g·pa-1s-1m−1). These results are consistent with other research on various nanocomposite membranes [54], and may be due to the incorporation of TiO2 NPs and GO in the PAN/β-CD matrix will result in forming H-bonds between the oxygen-containing functional groups in the TiO2 NPs/GO and the hydroxyl groups of the β-CD. This would enhance the molecular chains and reduce the availability of hydroxyl groups that interact with water, thereby reducing the free space of the membrane network and creating a more compact structure, thus resulting in a matrix with lower moisture absorption [50]. In addition, since it is generally believed that the permeability of a gas through a membrane depends on its solubility and diffusivity in the membrane, higher solubility and diffusivity will result in greater permeability. There are 3 main reasons for the reduction of WVP in composite nanofibrous membranes loaded with nanofillers: (i) the tortuous path formed by the gas/water-impermeable GO layer extended the transfer path; (ii) the water-insoluble TiO2 NPs hindered the diffusion of water vapor molecules, thereby prolonging the path of water vapor movement; and (iii) the accessible hydroxyl groups were reduced because of the formation of H-bonds between TiO2/GO and the hydroxyl groups of β-CD [55], [56].

Table 2.

Swelling, water solubility and WVP of pure PAN/β-CD, PAN/β-CD/TiO2, PAN/β-CD/GO and different PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membrane under different ultrasonic time.

| Ultrasound time (min) | Samples |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN/β-CD | 10: 0 | 9:1 | 8:2 | 7:3 | 6:4 | 5:5 | 0:10 | ||

| Sw (%) | 0 | 287.67 ± 19.58Aa | 257.99 ± 15.76ABa | 248.70 ± 16.20ABCa | 198.18 ± 13.39Ca | 213.10 ± 16.57BCa | 235.36 ± 12.84ABCa | 249.98 ± 15.38ABCa | 228.18 ± 6.94BCa |

| 15 | 280.35 ± 16.47Aab | 246.69 ± 12.97ABab | 221.72 ± 16.58BCab | 181.06 ± 7.35Ca | 209.78 ± 12.60BCa | 217.76 ± 8.30BCab | 224.46 ± 12.84BCab | 211.06 ± 7.35BCab | |

| 30 | 225.81 ± 13.99Ab | 212.73 ± 9.23ABab | 205.11 ± 15.06ABab | 171.26 ± 9.70Ba | 193.54 ± 10.64ABa | 203.61 ± 10.44ABab | 209.03 ± 14.02ABab | 191.26 ± 9.70ABb | |

| 45 | 220.76 ± 13.24Ab | 196.68 ± 13.50ABb | 182.78 ± 13.47ABb | 167.72 ± 11.23Ba | 176.47 ± 12.31ABa | 183.66 ± 10.73ABb | 194.21 ± 12.36ABb | 182.88 ± 10.30ABb | |

| 60 | 274.85 ± 16.50Aab | 235.09 ± 14.52ABab | 201.38 ± 16.30Bab | 187.99 ± 13.36Ba | 208.58 ± 15.59Ba | 205.59 ± 10.50Bab | 212.65 ± 10.47Bab | 201.07 ± 8.44Bab | |

| WS (%) | 0 | 23.83 ± 3.47Aa | 18.21 ± 2.14ABa | 16.72 ± 2.03Ba | 13.69 ± 1.25Ba | 15.13 ± 0.85Ba | 15.99 ± 1.52Ba | 16.44 ± 2.40Ba | 16.15 ± 1.64Ba |

| 15 | 21.89 ± 3.22Aa | 16.85 ± 1.50ABa | 16.43 ± 1.50ABa | 12.98 ± 1.36Ba | 13.99 ± 1.12Ba | 15.18 ± 0.75Ba | 15.74 ± 1.73Ba | 16.08 ± 1.58ABa | |

| 30 | 18.54 ± 3.05Aa | 15.90 ± 1.75ABa | 15.40 ± 1.83ABa | 11.73 ± 1.20Ba | 13.13 ± 1.03ABa | 14.88 ± 0.90ABa | 15.41 ± 0.85ABa | 15.41 ± 0.97ABa | |

| 45 | 17.50 ± 2.66Aa | 15.10 ± 1.54ABa | 15.41 ± 1.42ABa | 11.60 ± 1.15Ba | 13.06 ± 0.94ABa | 14.36 ± 1.01ABa | 15.22 ± 1.00ABa | 15.76 ± 0.85ABa | |

| 60 | 20.18 ± 2.95Aa | 17.48 ± 1.72ABa | 16.32 ± 1.78ABa | 12.79 ± 1.36Ba | 14.46 ± 1.16ABa | 15.21 ± 1.16ABa | 16.29 ± 1.12ABa | 16.52 ± 1.26ABa | |

| WVP (10-10 g·pa-1s-1m−1) | 0 | 3.18 ± 0.39Aa | 1.57 ± 0.27BCab | 1.53 ± 0.26Ca | 1.33 ± 0.12Ca | 1.70 ± 0.07BCa | 1.78 ± 0.20BCa | 2.44 ± 0.29ABa | 2.02 ± 0.26BCa |

| 15 | 2.70 ± 0.15Aab | 1.44 ± 0.22Cab | 1.28 ± 0.18Ca | 1.19 ± 0.08Ca | 1.55 ± 0.10BCab | 1.69 ± 0.18BCa | 2.14 ± 0.20ABa | 1.84 ± 0.30BCa | |

| 30 | 2.59 ± 0.21Aab | 1.31 ± 0.11BCab | 1.17 ± 0.14Ca | 1.06 ± 0.15Ca | 1.30 ± 0.04BCbc | 1.49 ± 0.18BCa | 1.29 ± 0.16BCb | 1.76 ± 0.15Ba | |

| 45 | 2.09 ± 0.10Ab | 1.13 ± 0.17BCb | 1.10 ± 0.09BCa | 1.00 ± 0.10Ca | 1.07 ± 0.08BCc | 1.48 ± 0.13Ba | 1.15 ± 0.17BCb | 1.23 ± 0.12BCa | |

| 60 | 2.50 ± 0.19Aab | 2.13 ± 0.34ABa | 1.52 ± 0.31BCa | 1.34 ± 0.20Ca | 1.60 ± 0.14BCab | 1.90 ± 0.05ABCa | 1.28 ± 0.16Cb | 1.98 ± 0.18ABCa | |

Ultrasound treatment will affect the Sw, WS, and WVP of nanofibrous membranes. The Sw, WS, and WVP of the nanofibrous membranes decreased initially and then increased with increasing ultrasonic time, although there was no significant difference (p > 0.05). For a TiO2-to-GO mass ratio of 8:2, the minimum value was reached after 45 min of ultrasound, at which point the Sw, WS, and WVP of the composite nanofibrous membrane were 167.72 ± 11.23%, 11.60 ± 1.15%, and 1.00 ± 0.10%, respectively, which were 15.37%, 15.61%, and 24.81% lower than the values without ultrasonic treatment. This may be due to the cavitation and kinetic energy of ultrasound causing the nanofillers to become more evenly distributed and more tightly combined with the PAN/β-CD matrix, which enhanced the intermolecular strength and made the diffusion path of gas molecules in the PAN/β-CD matrix curved, thereby reducing the Sw, WS, and WVP [57]. Prolonging the ultrasonic time to 60 min, however, may have a bad effect on the polymer. The thermal effect enhanced the movement of molecules, reduced the viscosity of the polymer solution, and formed many pores on the surface of polymer, thereby increasing the Sw, WS, and WVP to a certain extent [58].

Values with the same letter are not statistically different, according to Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05. a, b, c: mean values with the same letter in the same column are not significantly different (p > 0.05) (t = 8). A, B, C, D: mean values with the same letter in the same row are not significantly different (p > 0.05) (t = 8).

3.10. Mechanical properties

Mechanical properties are the major indices affecting the long-term stability of water treatment membranes. Table 3 lists the mechanical properties of different nanofibrous membranes. As the TiO2-to-GO mass ratio increased, the tensile strength (TS) of the nanofibrous membranes increased initially and then decreased. When the mass ratio of TiO2-to-GO was 8:2, the TS of the nanofibrous membranes reached a maximum value of 7.48 ± 0.54 MPa, which was 102.16% higher than that of the PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membrane (3.70 ± 0.28 MPa). The elongation at break (EAB) trend was opposite that of TS, decreasing initially and then increasing. Wang et al. reported the similar results [32]. There are four main reasons for the changes in the mechanical properties: (i) they may be due to the strong interactions among the molecular chains of PAN/β-CD, TiO2 NPs, and GO nanosheets, which improved the intramolecular cohesion between PAN/β-CD and TiO2/GO and caused a decrease of fragment mobility [55]; (ii) the size-effect of the nanofibers conducive to improving the mechanical property. Meanwhile, the electrostatic force generated during electrospinning can enhance the interaction among PAN/β-CD, TiO2 NPs, and GO sheets, and [34]; (iii) the high surface area and good dispersion of TiO2 NPs and GO can absorb the PAN chains on the surface, thereby promoting the effective stress transfer from the PAN chains to the TiO2 NPs or GO nanosheets and improving the mechanical properties of the composite nanofibrous membranes [53]; and (iv) the electrospinning theory indicates that smaller fiber diameters are expected to produce better mechanical properties [59]. The SEM results revealed that the diameter of the nanofibrous membrane was the smallest when the mass ratio of TiO2-to-GO was 8:2, which is consistent with the mechanical performance results. In addition, the mechanical properties of the PAN/β-CD/TiO2 and PAN/β-CD/GO nanofibrous membranes were worse than those of the PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes, possibly because the mechanical properties of membrane materials are mainly related to the interfacial adhesion in the polymer matrix and the dispersion of nanofillers [60]. Nanofillers readily agglomerated when only TiO2 NPs or GO was added, which reduced the contact area and interaction between the nanofillers and the PAN/β-CD polymer matrix, resulting in poor mechanical properties [61].

Table 3.

TS and EAB of pure PAN/β-CD, PAN/β-CD/TiO2, PAN/β-CD/GO and different PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membrane under different ultrasonic time.

| Ultrasound time (min) | Samples |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN/β-CD | 10: 0 | 9:1 | 8:2 | 7:3 | 6:4 | 5:5 | 0:10 | ||

| TS (MPa) | 0 | 3.70 ± 0.28Ca | 4.46 ± 0.25Ca | 6.62 ± 0.61ABa | 7.48 ± 0.54Aa | 7.17 ± 0.60Aa | 6.79 ± 0.57ABa | 6.22 ± 0.46ABa | 5.35 ± 0.57BCa |

| 15 | 3.98 ± 0.30 Da | 4.59 ± 0.37CDa | 6.74 ± 0.08ABa | 7.56 ± 0.56Aa | 7.32 ± 0.60Aa | 6.83 ± 0.13ABa | 6.30 ± 0.29ABa | 5.41 ± 0.60BCa | |

| 30 | 4.15 ± 0.24 Da | 4.73 ± 0.41CDa | 6.77 ± 0.37Aa | 7.70 ± 0.37Aa | 7.54 ± 0.54Aa | 6.95 ± 0.30Aa | 6.44 ± 0.30ABa | 5.50 ± 0.37BCa | |

| 45 | 4.29 ± 0.25 Da | 4.85 ± 0.38CDa | 6.93 ± 0.40ABa | 7.79 ± 0.52Aa | 7.57 ± 0.34Aa | 6.98 ± 0.36ABa | 6.60 ± 0.25ABa | 5.80 ± 0.46BCa | |

| 60 | 3.83 ± 0.10 Da | 4.54 ± 0.30CDa | 6.52 ± 0.55ABa | 7.44 ± 0.49Aa | 7.22 ± 0.45Aa | 6.80 ± 0.29Aa | 6.26 ± 0.29ABa | 5.40 ± 0.41BCa | |

| EAB (%) | 0 | 76.50 ± 4.03Aa | 68.47 ± 3.65ABa | 55.64 ± 2.36Ca | 52.21 ± 1.40Ca | 54.06 ± 1.70Ca | 58.77 ± 2.73Ca | 61.63 ± 2.25BCa | 69.49 ± 3.01ABa |

| 15 | 74.75 ± 5.11Aa | 67.20 ± 3.38ABCa | 54.26 ± 1.88 Da | 52.00 ± 1.33 Da | 53.86 ± 1.44 Da | 58.13 ± 2.67CDa | 60.30 ± 1.69BCDa | 68.02 ± 2.68ABa | |

| 30 | 73.30 ± 3.92Aa | 66.36 ± 3.03ABa | 53.74 ± 2.04Ca | 50.79 ± 0.83Ca | 51.70 ± 1.62Ca | 57.30 ± 2.42Ca | 58.83 ± 2.03BCa | 65.72 ± 2.23ABa | |

| 45 | 71.01 ± 3.60Aa | 65.69 ± 2.70Aa | 53.40 ± 2.12Ca | 50.57 ± 1.05Ca | 50.35 ± 0.90Ca | 56.76 ± 1.67BCa | 57.50 ± 1.86BCa | 63.79 ± 1.90ABa | |

| 60 | 73.38 ± 2.89Aa | 67.35 ± 2.83Aa | 54.46 ± 2.31Ba | 51.52 ± 1.24Ba | 51.50 ± 1.03Ba | 57.35 ± 1.48Ba | 58.37 ± 1.50Ba | 66.46 ± 2.15Aa | |

With the extension of the ultrasonic time, the TS of the nanofiber membranes increased initially and then decreased. When the ultrasonic time was 45 min, the TS reached a maximum value of 7.79 ± 0.52 MPa (TiO2:GO = 8:2), which was 4.14% lower than the TS without ultrasonic treatment. Jatoi et al. reported the similar results, they found that the TS of PAN nanofibers increased during the ultrasonic dyeing process, possibly due to the ultrasonic cavitation effect that makes the nanofibers stiffen [4]. Moreover, the agglomeration of nanofillers can be broken under proper ultrasonic action, which makes them disperse more uniformly, thereby enhancing the interaction among PAN/β-CD, TiO2 NPs, and GO. An excessively long sonication time (60 min), however, may cause the PAN polymer chains to open under the influence of ultrasonic cavitation and high temperature, disturbing the molecular arrangement and causing a deterioration in mechanical properties [4].

Values with the same letter are not statistically different, according to Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05. a, b, c: mean values with the same letter in the same column are not significantly different (p > 0.05) (t = 8). A, B, C, D: mean values with the same letter in the same row are not significantly different (p > 0.05) (t = 8).

3.11. Effect of different nanofibrous membranes on photocatalytic dye degradation

MB (cationic) and MO (anionic) were selected as models because they are two of the major pollutants in the textile and dye industry. According to the above results, it was found that after 45 min of ultrasonication, the nanofillers were uniformly dispersed on the surface and inside of the nanofibers, and the size of the agglomerates decreased significantly (showed by EDS and TEM images) due to the kinetic and thermal energy generated by ultrasonic cavitation acting on large agglomerates [37], and the diameter of the nanofibrous membrane after ultrasonic treatment was significantly smaller than the diameter without ultrasonic treatment. The smaller the diameter, the larger the specific surface area of nanofibers, which can provide more adsorption sites, thereby promoting photocatalysis [1]. In addition, the composite nanofibrous membrane had strong practicability because under this ultrasonic condition, Sw, WS and WVP were the lowest and the TS was the largest. Therefore, the removal efficiency of MB and MO by different nanofibrous membranes (ultrasonic time: 45 min) under natural light was studied and the results are presented in Fig. 8. The minimal degradation rate was observed in the aqueous solution of MB and MO, indicating the high stability of dyes under natural light, and that fact that the dyes could not be effectively degraded without a suitable absorbent or photocatalyst. The degradation rate of MB (6.73 ± 1.06%) was slightly higher than that of MO (2.63 ± 0.15%). This is because MB can self-degrade under UV light, so the UV beam in natural light can promote the degradation of MB to a certain extent [62]. To investigate the effect of the photocatalyst on the degradation of the dyes in nanofibrous membranes, the membrane samples were first stirred for 1 h under dark conditions in order to achieve adsorption–desorption equilibrium, so as to eliminate the effect of the photocatalytic reaction on MB and MO removal efficiency. It can be seen from Fig. 8 that after 60 min of adsorption under dark conditions, each fiber membrane exerted a certain adsorption effect on MB and MO. Pure PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membranes adsorbed 32.84 ± 2.13% of MB and 27.35 ± 1.59% of MO, which was mainly due to the fact that: (i) β-CD is an excellent adsorbent as a result of its special hydrophobic cavity and hydrophilic outer wall structure, and there is an electrostatic interaction between the electronegative PAN and the cationic dye MB [16]; and (ii) the nanofibers prepared by electrospinning had a small diameter and large porosity, and the SEM results revealed that all nanofibers exhibited a rough and porous morphology. Therefore, the large surface and plentiful active sites of the fibrous material available for the adsorption provided them with a better adsorption effect [7]. After adding nanofillers, as the mass ratio of TiO2-to-GO continued to decrease, the adsorption rate of MB and MO in the composite nanofibrous membranes exhibited an upward trend. The adsorption rates of PAN/β-CD/GO nanofibrous membranes on MB and MO attained maxima of 64.80 ± 1.83% and 57.45 ± 0.84%, respectively, which were 97.32% and 110.05% higher than the rates of the pure PAN/β-CD nanofibrous membranes. This was mainly due to the fact that a low concentration of GO is a non-toxic absorbent with good biocompatibility, which can capture organic pollutants through π-π or electrostatic interaction and hydrogen bonding [63]. In addition, since the negatively charged GO surface contribute to the adsorption of cationic dye, the adsorption of the MB was stronger than MO [34]. Compared with the PAN/β-CD/GO nanofibrous membrane, the reason that the adsorption rate of the nanofibrous membranes containing TiO2 was low may be that the TiO2 NPs on the surface of the fiber hindered the adsorption of the dye by the fibrous membrane, as well as the relatively low GO content, Zhan et al. reported the similar results [64]. The color changes of the solution before and after adsorption are illustrated in Fig. 8 (c), which further proved the adsorption effect of the nanofibrous membranes on the dyes.

Fig. 8.

Degradation efficiencies of (a1) MB and (b1) MO by various nanofibrous membranes under natural light; (a2) and (b2) the colors of the MB and MO solutions after adsorption for 1 h; (a3) and (b3) the colors of the MB and MO solutions after photocatalysis.

In order to simulate the degradation of the dyes under natural conditions, each sample was moved outdoors (noon on a sunny day in May 2020; Yaan, China; 29.98°N, 103.00°E; outside temperature: 26–32 °C) after 1 h. The results revealed that after 5 h, the removal rates of MB and MO were highest in the nanofiber membrane (TiO2:GO = 8:2), i.e., 93.52 ± 1.83% and 90.92 ± 1.52%, respectively. The effect of pure PAN/β-CD and PAN/β-CD/GO nanofibrous membranes on the removal of dyes under natural light was not obvious, because there was no photocatalyst (TiO2). The relative degree of MB and MO degradation was 8:2 > 7:3 > 9:1 > 10:0 > 6:4 > 5:5, indicating that a small number of GO can improve the photocatalytic activity of TiO2, while an excessive GO concentration will reduce the light absorption of TiO2, resulting in a decrease of the photoactivity. Velasco-Hernández et al. reported the similar results [65]. It has been reported that the loading of GO materials can improve the photocatalytic performance of TiO2, which is mainly due to the two-dimensional profile. GO can act as an electron collector and exhibit high charge mobility through conjugation with the π bond of GO, and the surface interaction of TiO2 with GO caused by the π unpaired electrons of GO extend the absorption interval towards the visible spectrum, thereby increasing the recombination time of the electron-hole pair and improving light utilization [46]. In addition, previous studies have shown that β-CD can improve the electron transfer on the surface of TiO2 and enhance the adsorption of pollutants to promote the photocatalytic degradation of the pollutants on the surface of TiO2 [9].

3.12. Effect of pH value on photocatalytic dye degradation

The pH value of the solution affects the photocatalytic degradation of dye molecules from two aspects: i) the adsorption-desorption equilibrium of the dye molecule on the surface of nanofibrous membranes depends on pH, and ii) The pH value of the dye solution will affect the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the photocatalytic degradation of dyes on nanofibrous membranes, and it can also affect the adsorption capacity by changing the surface active site of the adsorbent materials and the aqueous chemistry of the dye molecule [66]. The PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membrane (TiO2:GO = 8:2, ultrasonic time = 45 min) was selected to evaluate the effect of pH value on the degradation rates of the MB and MO dyes (Fig. 9). It can be seen from Fig. 9a that during the adsorption process, the removal rate of MB by the nanofibrous membrane increased as the pH value increased. The poor adsorption capacity of the nanofibrous membrane under acidic conditions may be due to the positive charge on the nanofiber surface. —OH2+ and —COOH2+ will be generated by the protonation of the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in GO, which limit the attraction of cationic dyes to the surface of the nanofibrous membrane due to electrostatic repulsion. As the pH increases, —OH2+, —COOH2+, and NH2+ on the nanofibrous membrane surface are deprotonated to carry negative charges, resulting in electrostatic adsorption between the nanofibrous membrane and MB, thereby enhancing the adsorption effect [37]. Bu et al. found the similar results [67]. The removal rate of the anion dye MO by the nanofibrous membrane was opposite that of the cationic dye MB in the adsorption process (Fig. 9b). The photocatalysis degradation of MB and MO exhibited a downward trend with increasing pH under natural conditions. At pH = 3, the photodegradation efficiency levels of the nanofibrous membrane for MB and MO were 96.62 ± 0.94% and 92.4 ± 0.93%, respectively. When the pH increased to 11, the photodegradation efficiency levels for MB and MO decreased to 88.58 ± 1.38% and 80.23 ± 1.27%, respectively, indicating that acidic conditions are more conducive to photocatalysis. The higher photodegradation efficiency of MB and MO in an acidic solution can be explained by the fact that electrons readily react with O2 to generate H2O2 in an acidic environment, and then H2O2 further generates (Eqs. (5), (7)–(9)), is the main active substance in the photocatalytic process, thus accelerating catalytic rate [64]. Zhan et al. reported the similar results [64]. In addition, the reason that the MB removal rate was still higher under alkaline conditions may be due to the fact that the cationic dye MB has more adsorption per unit volume, generating a large number of reactive sites compared with the anion dye MO, which enhances the degradation rate in natural light [27]. Interestingly, the results of Chaúque et al. showed that in a weakly acidic media (pH = 5), the quantitative transfer of hydrogen ions from MO molecule to nanocomposites was higher, and decreased either as the concentration of hydrogen ions increased or in a neutral to alkaline medium [67].

Fig. 9.

Effect of pH values in the degradation efficiencies of (a1) MB and (b1) MO by PAN/CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes (TiO2:GO = 8:2, ultrasonic time: 45 min) under natural light; (a2) and (b2) the colors of the original solution; (a3) and (b3) the colors of the MB and MO solutions after adsorption for 1 h; (a4) and (b4) the colors of the MB and MO solutions after photocatalysis.

3.13. Effect of initial concentration on photocatalytic dye degradation

The effect of the initial dye concentration on degradation performance plays an important role in exploring the photodegradation efficiency of dyes in the photodegradation mechanism. At pH = 3, the removal rate of the dye molecules on the same quality PAN/CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes (TiO2:GO = 8:2, ultrasonic time = 45 min) under natural light irradiation was investigated using different initial concentrations (Fig. 10). The results revealed that the removal rates of MB and MO both decreased with increasing initial concentration. The removal rates of MB were 96.62 ± 0.94%, 93.42 ± 1.23%, 90.06 ± 1.30%, 84.40 ± 1.32%, and 81.60 ± 1.63%, corresponding to concentrations of 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 ppm. Moreover, for MO, the photodegradation efficiencies were 93.84 ± 0.78%, 89.47 ± 1.83%, 85.60 ± 1.20%, 79.16 ± 1.63%, and 76.82 ± 1.82%, corresponding to concentrations of 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 ppm. This is mainly because the number of membrane samples was kept constant; thus, the number of available active sites on the nanofibrous membrane remained unchanged. The higher removal rates of the MB and MO dyes at lower concentrations can be referred to when studying the interaction of all of the dye molecules in an aqueous solution with binding sites on the nanofibrous membrane surface. The removal rates may be affected by the overload of the nanofibrous membrane sites by large amounts of dye [26], however. Chaúque et al. reported the similar results [66]. They attributed the results to the high affinity of dye molecules for the surface of the calcined TiO2-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-ethylenediamine-PAN nanofibrous composites and the ROS generated on the surface of the nanofibrous composites due to UV radiation exposure. Therefore, before the active adsorption sites were depleted, the photocatalytic degradation of dye molecules in contact with the TiO2 occurred. So, the dye molecules continuously migrated to the nanofibrous composite surface took place until quantitative degradation was achieved.

Fig. 10.

Effect of intial concentration in the degradation efficiencies of (a1) MB and (b1) MO by PAN/CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes (TiO2:GO = 8:2, ultrasonic time: 45 min) under natural light; (a2) and (b2) the colors of the original solution; (a3) and (b3) the colors of the MB and MO solutions after adsorption for 1 h; (a4) and (b4) the colors of the MB and MO solutions after photocatalysis.

3.14. Reusability of PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membranes

Since the reusability of nanofibrous membranes may be an important evaluation indicator for their potential applications, the MB and MO dyes were tested five times in order to investigate the reusability of PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membranes (TiO2:GO = 8:2, ultrasonic time = 45 min) (Fig. 11). The results revealed that the adsorption and photodegradation of MB and MO by PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membranes exhibited good stability and reusability. This may be related to the low density of PAN and the porosity of the PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes, which easily floated on the surface of the dye solution, making them easy to recover during the recycling process [27]. During the three cycles, the degradation efficiency of MB and MO by the nanofibrous membranes was maintained at 80%, while it decreased to 68.42 ± 1.47% and 65.13 ± 1.37% in the fifth cycle, respectively. The degradation change was mainly due to the loss of nanofibrous membranes and the reduction of the photocatalyst TiO2 content during use. In addition, reusability may be related to the combination of components. Yu et al. obtained AgI NPs by the physical adsorption and subsequent gas/solid reaction adhered to the surface and edges of TiO2/PAN hybrid nanofibers. They found that AgI was directly connected to the dyes during the photocatalytic process, and might be lost due to constant stirring, resulting in a reduction in the efficiency of dye degradation [13]. PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes prepared in this experiment, the existence of TiO2 was diverse, not only inside the fibers, but also on the surface and between the fibers, most of which formed a heterostructure with GO (as seen in SEM and TEM). Therefore, they may have been in circulation during the recycling process.

Fig. 11.

Cycles of degradation efficiencies of (a) MB and (b) MO by PAN/CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes (TiO2:GO = 8:2, ultrasonic time: 45 min) under natural light.

Adsorption and photocatalytic mechanism

The possible adsorption and photodegradation mechanism of PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membranes to degrade MB and MO are as the following points: (i) the nanofibers prepared by electrospinning exhibit a rough and porous morphology, with a small diameter and a large degree of porosity; hence, the fibrous material has a large surface and many adsorption active sites, making it more adsorbent [7]; (ii) there is an electrostatic interaction between the electronegative PAN and the cationic dye MB; (iii) β-CD is an excellent adsorbent due to its special hydrophobic cavity and hydrophilic outer wall structure; it can encapsulate various hydrophobic molecules in its cavity through non-covalent host-guest interactions and hydrophilic molecules on the surface through covalent interaction; and (iv) GO is a non-toxic absorbent with good biocompatibility, which can capture organic pollutants through π-π interaction, cation-π bonding, or electrostatic interaction and hydrogen bonding [63]. In addition, the negatively charged GO can provide the adsorption of cationic dye, so the adsorption of the MB (cationic dye) is stronger than MO (the anionic dye) [37].

The photocatalytic activity of PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membranes can be explained as follows. The photodegradation of dyes is generally due to electrons (e−) and holes (h+) generated during the photocatalysis process (Eq (4)). Delaying the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs can allow more h+ to initiate redox reactions with dyes and improve photocatalytic efficiency [15]. The π unpaired electrons of GO cause the surface interaction of TiO2 with GO and the transfer of TiO2 electrons to GO, thereby increasing the recombination time of electron-hole pairs [46]. When the nanofibrous membrane is exposed to light, the TiO2 electrons change from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), and generate h+ at the VB and e− at the CB. These photogenerated h+ and e− move to the surface of the nanofiber. During the formation of electron-hole pairs, some ROS are generated, i.e. hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide radical anions () (Eq (5), (6), (7), (8), (9)). These , radicals and h+ readily react with MB and MO to form reduction products and lead to dye degradation (Eq (10)) [68], as shown in the following mechanism. The generation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) is the main factor of photocatalytic activity, in which both h+ and e− are involved at the VB and the CB, respectively. The highly oxidative nature of h+ among •OH radicals will partially or completely degrade organic dyes [13].

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

3.15. Antimicrobial properties

The microorganisms in the water will adhere to the membrane surface and resulting in reduced purification efficiency. Therefore, studying the antibacterial property of the nanofibers plays an important role in the antifouling properties of membrane [34]. The antibacterial activities of different nanofibrous membranes against E. coli and S. aureus are presented in Fig. 12 and Table 4. As expected, the pure PAN/β-CD fiber films had no bacteriostatic effect. After adding TiO2 NPs and GO, however, the antibacterial activity of the nanofibers was significantly enhanced (p < 0.05). Relatively speaking, the antibacterial activity of PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO > PAN/β-CD/TiO2 > PAN/β-CD/GO, which was consistent with the photocatalytic dye degradation test results. The PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membrane displayed the strongest bacteriostatic effect, with E. coli and S. aureus inhibition zones of 16.81 ± 0.23 mm and 13.97 ± 0.12 mm, respectively, which may be due to the synergistic antibacterial effect of TiO2 NPs and GO [14]. The antibacterial activity of TiO2 NPs was primarily related to their shape, size, and crystal structure, as well as the light conditions. TiO2 NPs absorbed UV light when the composite nanofibrous membranes were exposed to UV light, causing the electrons to jump from their VB to their conduction band CB. Photogenerated electrons of the CB react with oxygen to generate ROS, such as superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxide radicals (OH), which may inactivate microorganisms by affecting genomes and other intracellular molecules, thus causing cell lysis when irradiated TiO2 NPs are released and come in contact with microorganisms [69]. It has been reported that the loading of GO material can improve the photocatalytic performance of TiO2 NPs and further improve the antibacterial activity of fibrous membranes [46]. The inhibition zone of the PAN/β-CD/GO nanofibers against E. coli and S. aureus was smaller than those of the nanofibrous membranes containing TiO2 NPs, which were 12.62 ± 0.20 mm and 10.83 ± 0.20 mm, respectively. This is because GO has a weaker killing capacity against bacteria than TiO2 NPs. Filina et al. found that the GO/PLL membrane did not cause significant cell death [70].

Fig. 12.

Effect of PAN/β-CD, PAN/β-CD/TiO2, PAN/β-CD/GO and PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes on the growth inhibition of (a) E. coli and (b) S. aureus for 24 h after incubation at 37 ℃.

Table 4.

Inhibition zone diameter of different membranes (ND indicates the absence of inhibition zone detected).

| Samples | Ultrasound time (min) | Inhibition zone diameter (mm) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | S. aureus | ||

| PAN/β-CD | 0 | ND | ND |

| PAN/β-CD/TiO2 | 0 | 16.45 ± 0.16b | 13.08 ± 0.28c |

| PAN/β-CD/GO | 0 | 12.62 ± 0.20a | 10.83 ± 0.20d |

| PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO | 0 | 16.81 ± 0.23ab | 13.97 ± 0.12b |

| PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO-15 | 15 | 17.01 ± 0.12a | 14.05 ± 0.19b |

| PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO-30 | 30 | 17.14 ± 0.16a | 14.13 ± 0.06b |

| PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO-45 | 45 | 17.22 ± 0.08a | 14.23 ± 0.09b |

| PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO-60 | 60 | 17.30 ± 0.11a | 14.85 ± 0.14a |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Ultrasonic treatment can improve the antibacterial effect of PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibrous membranes. After 1 h of sonication, the E. coli and S. aureus inhibition zones increased significantly, to 17.30 ± 0.11 and 14.85 ± 0.14 mm, respectively, which were 2.91% and 6.30% higher than the membranes without sonication. Zhang et al. reported similar results [56]. Related research shows that the smaller the particle size of the NPs, the stronger the antibacterial effect. Therefore, issues such as deagglomeration treatment before adding TiO2 NPs and GO to polymer materials, as well as the degree to which NPs are dispersed within the polymer, both will affect the antibacterial property of the final composite. TiO2 NPs can be well dispersed and uniformly attached to the surface of the GO under ultrasonic conditions, which increases the interaction between the TiO2 NPs and the GO, resulting in a larger surface area and increasing the possibility of contact between nanowires and microbial cells, thereby enhancing the antibacterial effect [20]. In addition, the kinetic energy and thermal effects produced by ultrasonic treatment make it easier for the release of TiO2 and GO in the polymer, improving the antibacterial activity [71]. Therefore, the use of ultrasonic treatment to improve the antibacterial properties of nanofibrous membranes is worthy of further research.

4. Conclusions

PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO nanofibers were prepared using electrospinning technology combined with ultrasonic-assisted electrospinning, and the effects of different TiO2-to-GO mass ratios and ultrasonic times on membrane properties were investigated. The results showed that a TiO2-to-GO mass ratio of 8:2 and the ultrasonic time for 45 min was the best condition to improve the overall performance. TiO2 NPs can be well dispersed and uniformly attached to the surface of GO sheets by ultrasonic cavitation, making the nanofibers has the best mechanical properties, barrier properties and practicability, and showed good adsorption and photocatalytic activity for MB and MO. And showed excellent antibacterial properties against E. coli and S. aureus. Therefore, this novel PAN/β-CD/TiO2/GO composite nanofibrous membrane has good application potential in water pollution treatment and repair.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Rong Zhang: Writing - original draft. Yanlan Ma: Writing - review & editing. Wenting Lan: Writing - review & editing. Dur E Sameen: Data curation. Saeed Ahmed: Formal analysis. Jianwu Dai: Software. Wen Qin: Conceptualization. Suqing Li: Investigation. Yaowen Liu: Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51703147), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2018RZ0034), and Natural Science Fund of Education Department of Sichuan Province (16ZB0044 and 035Z1373).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105343.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Jaseela P.K., Garvasis J., Joseph A. Selective adsorption of methylene blue (MB) dye from aqueous mixture of MB and methyl orange (MO) using mesoporous titania (TiO2) – poly vinyl alcohol (PVA) nanocomposite. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;286 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qayum A., Wei J., Li Q., Chen D., Jiao X., Xia Y. Efficient decontamination of multi-component wastewater by hydrophilic electrospun PAN/AgBr/Ag fibrous membrane. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;361:1255–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao F., Guo X., Li J., Sun H., Zhang H., Wang W. Electrospinning preparation and dye adsorption capacity of TiO2@Carbon flexible fiber. Ceram. Int. 2019;45(9):11856–11860. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jatoi A.W., Gianchandani P.K., Kim I.S., Ni Q.Q. Sonication induced effective approach for coloration of compact polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofibers. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;51:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia S., Tang D., Peng J., Sun Z., Yang X. beta-Cyclodextrin modified electrospinning fibers with good regeneration for efficient temperature-enhanced adsorption of crystal violet. Carbohyd. Polym. 2019;208:486–494. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sikder M.T., Rahman M.M., Jakariya M., Hosokawa T., Kurasaki M., Saito T. Remediation of water pollution with native cyclodextrins and modified cyclodextrins: A comparative overview and perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;355:920–941. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abd-Elhamid A.I., El-Aassar M.R., El Fawal G.F., Soliman H.M.A. Fabrication of polyacrylonitrile/β-cyclodextrin/graphene oxide nanofibers composite as an efficient adsorbent for cationic dye. Environ. Nanotechnol., Monitoring Manage. 2019;11 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y., Li Q., Gao Q., Wan S., Yao P., Zhu X. Preparation of Ag/β-cyclodextrin co-doped TiO2 floating photocatalytic membrane for dynamic adsorption and photoactivity under visible light. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2020;267 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang G., Fan W., Li Q., Deng N. Enhanced photocatalytic New Coccine degradation and Pb(II) reduction over graphene oxide-TiO2 composite in the presence of aspartic acid-beta-cyclodextrin. Chemosphere. 2019;216:707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prahsarn C., Klinsukhon W., Roungpaisan N. Electrospinning of PAN/DMF/H2O containing TiO2 and photocatalytic activity of their webs. Mater. Lett. 2011;65(15–16):2498–2501. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu C., Liu G., Han K., Ye H., Wei S., Zhou Y. One-step facile synthesis of graphene oxide/TiO2 composite as efficient photocatalytic membrane for water treatment: Crossflow filtration operation and membrane fouling analysis. Chem. Eng. Process. 2017;120:20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fathinia M., Khataee A. Photocatalytic ozonation of phenazopyridine using TiO2 nanoparticles coated on ceramic plates: mechanistic studies, degradation intermediates and ecotoxicological assessments. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2015;491:136–154. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu D., Bai J., Liang H., Ma T., Li C. AgI-modified TiO2 supported by PAN nanofibers: A heterostructured composite with enhanced visible-light catalytic activity in degrading MO. Dyes and Pigments. 2016;133:51–59. [Google Scholar]