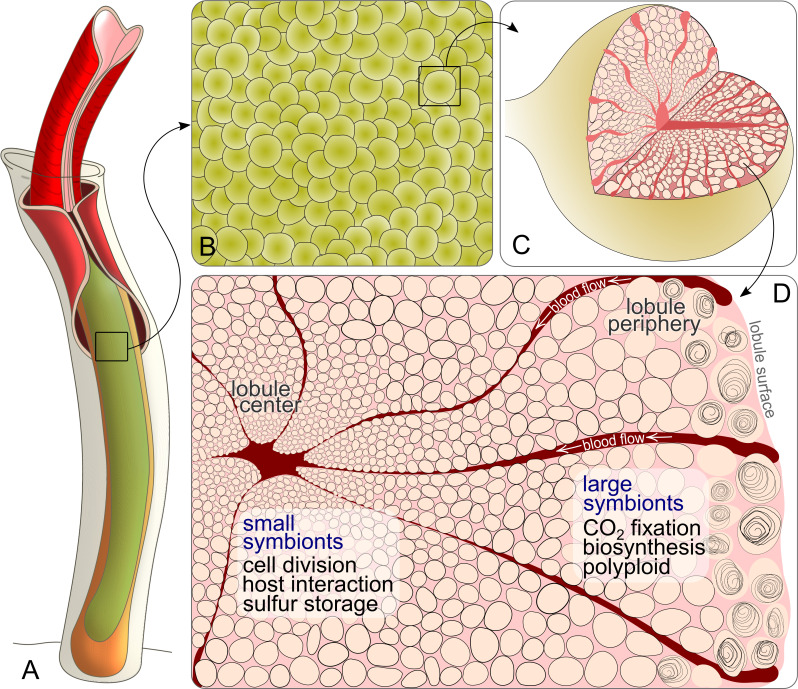

Figure 6. Schematic drawing of Riftia symbiont cells inside the trophosome.

(A) An adult tubeworm reaches 2 m in body length. Its symbiont-containing organ, the trophosome (green), fills most of the body cavity (coelomic cavity), and is immersed in coelomic (non-vascular) blood (not shown). (B) Close-up of the lobular trophosome tissue. (C) Single lobule (200–500 µm in diameter) with interior blood vessels (blood-filled spaces) and symbiont cells visible. (D) Cross-section through a trophosome lobule (similar to that in Figure 5A) with small symbiont cells located in the center around an efferent blood vessel. Symbiont cell size increases toward the lobule periphery, where the largest symbionts are digested by the host (curls). Blood flow from lobule periphery to lobule center may cause gradients in nutrient availability. Based on the results of this study, the most striking characteristics of small and large symbionts, which determine their respective roles in the symbiosis, are indicated. Note that this is a simplified illustration, in which the various kinds of host cells (including their membranes, nuclei and organelles), as well as blood vessels or gonads that line the surface of the trophosome were omitted for clarity’s sake. (Illustrations based on drawings, TEM images and descriptions by van der Land and Nørrevang, 1977; Felbeck and Turner, 1995; Bright and Sorgo, 2003).