Introduction

Perforating lichen nitidus is a very rare subtype of lichen nitidus (LN), featuring a central perforating channel within individual lesions of LN. Originally described in 1981 by Bardach,1 only 10 prior cases have been reported anecdotally worldwide. Like LN, the cause is unknown. It is also unclear why transepidermal perforation occurs in some individuals and what component is being extruded. Here, we present a case of perforating LN in an adult, describe both typical and novel clinicopathologic and dermoscopic characteristics, and review the literature of previous cases.

Case presentation

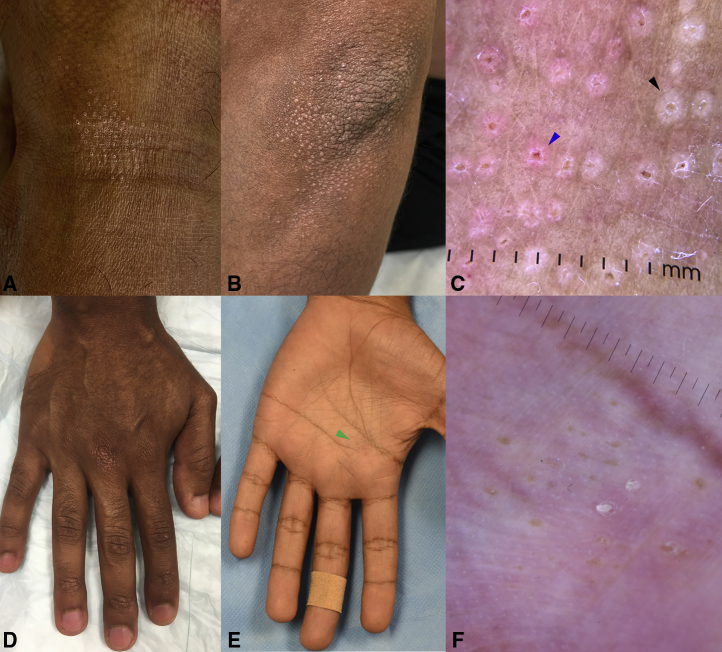

An otherwise healthy 32-year-old male, Fitzpatrick phototype IV, presented with a 2-month eruption of asymptomatic, symmetrically-distributed 1-2 mm white to pink molluscum-like umbilicated papules overlying the dorsolateral aspects of the finger and toe joints, palms and soles, extensor elbows and knees, and anterolateral ankles (Fig 1, A, B, D, E). No inciting trigger could be identified. Dermoscopy revealed pale-white papules with radial ridges emanating in a “sunburst” pattern from a depressed central keratotic core rimmed by fine white scale. Some lesions carried a pink hue and exhibited radial linear and hairpin vessels (Fig 1, C). Lesions of the glabrous hands were similar, but without visible vessels (Fig 1, F).

Fig. 1.

Clinical and dermoscopic features. White to pink umbilicated 1-2 mm papules overlying the (A) anterolateral ankles and (B) extensor elbows. C, On dermoscopy, pale-white papules with radial ridges emanating in a “sunburst” pattern from a depressed central keratotic core rimmed by fine white scale (black arrow) were observed. Some were pink and exhibited radial linear and hairpin vessels (blue arrow). Similar appearing lesions were present on the (D) dorsal finger joints and (E) palms. F, On the palm (green arrow in E), umbilicated papules had a yellow core with a peripheral pale-white halo. No vascular structures were visible.

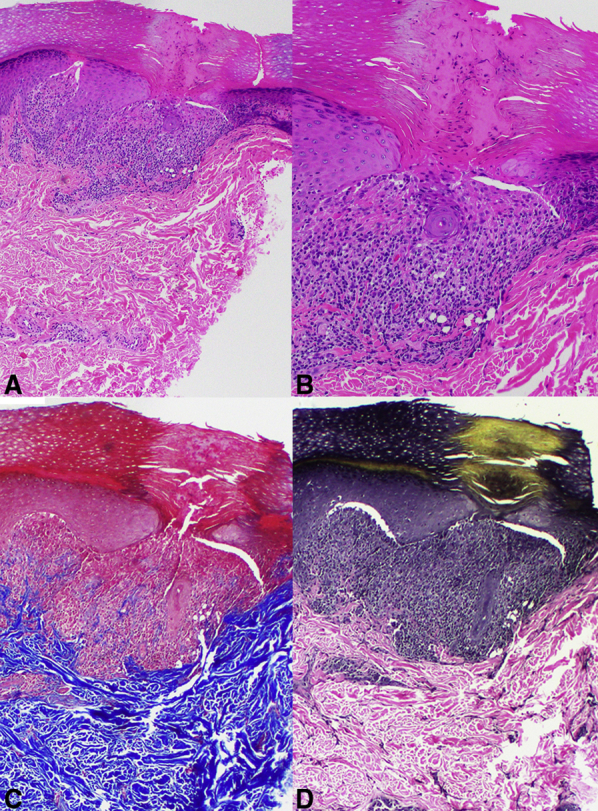

Punch biopsy of the dorsal third finger revealed focal expansion of dermal papillae with a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate bounded by elongated rete ridges. There was overlying epidermal atrophy and parakeratosis and a central transepidermal perforating channel containing inflammatory infiltrate and keratin (Fig 2, A, B). Elongated capillaries could be seen in the infiltrate and surrounding dermal papillae. Elastin and trichrome stains showed no transepidermal migration of elastic fibers or collagen, respectively (Fig 2, C, D). No foreign material was seen on polarized microscopy. Treatment with clobetasol 0.05% ointment resulted in flattening and resolution of nearly all lesions at 6-week follow-up.

Fig 2.

Histologic features. A, Punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the third finger. The classic “ball-in claw” of lichen nitidus is observed at low power, with a central channel of transepidermal elimination of keratin and inflammatory material. Adjacent to and within the infiltrate were superficial ectatic vessels. B, Higher power revealed abundant parakeratosis overlying the focus of the perforating channel. Within the perforating channel there was no extrusion of (C) collagen fibers or (D) elastic fibers (A and B, Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnifications: A, ×4; B, ×10; C, Trichrome stain; original magnification: ×10; and D, Elastin stain; original magnification: ×10.)

Discussion

Transepidermal perforation in LN is an exceedingly rare finding; only 10 cases have been reported worldwide (Table I).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 This case provides an in-depth clinical, dermoscopic, and histologic examination of this rare presentation.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of perforating lichen nitidus cases from the literature

| Cases | Country | Age (years) | Sex | Location | Symptoms | Duration | Clinical appearance | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present case | USA | 32 | Male | Dorsal finger joints, elbows, knees, and anterolateral ankles | Asymptomatic | 2 months | Symmetrically-distributed 1-2 mm white to tan papules, most of which had central umbilication | Near complete resolution of all lesions after using clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks |

| Li et al2 | China | 10 | Male | Trunk and upper limbs | Asymptomatic | 2 years | Numerous, discrete, flesh-colored, shiny 2 mm papules. Some were umbilicated | Topical corticosteroid for 2 weeks slightly improved lesions, but lesions returned after discontinuation |

| Martinez-Mera et al3 | Spain | 30 | Male | Dorsum of hands and fingers | Asymptomatic | 1 year | Numerous 1-mm umbilicated papules grouped into patches | Topical methylprednisolone aceponate once a day for several weeks with slight improvement and flattening of the lesions at 8-month follow-up |

| Zussman and Smart4 | USA | 25 | Male | Dorsal fingers | Asymptomatic | 1 year | Numerous small papules coalescing into plaques | No improvement with topical in-office acid treatment or topical clobetasol spray |

| Vijaya et al5 | India | 14 | Female | Dorsum of hands and feet | Asymptomatic | 6 months | Lichenoid, skin-colored shiny papules, some with umbilication | None reported |

| Arrue et al6 | Spain | 35 | Male | Lateral edges of the fingers | Asymptomatic | >20 years | Skin-colored, shiny firm monomorphic 1 mm papules | No response to topical steroids or tacrolimus |

| Yoon et al7 | Korea | 18 | Female | Hands, wrists, forearms, elbows and knees | Asymptomatic | 2 years | Multiple 1 mm skin-colored, flat shiny papules, densely distributed | No change after 6 months without treatment. Improvement after fluocinonide 0.05% ointment twice daily for 1 year |

| Yoon et al7 | Korea | 20 | Female | Wrists, elbows, knees and dorsal feet | Asymptomatic | 11 months | Multiple, pinpoint- to pinhead-sized, round or polygonal, flesh-colored, flat, and shiny papules. Some were umbilicated | Spontaneous clearance of multiple lesions after 6 months |

| Itami et al8 | Japan | 32 | Male | Hand, fingers | Asymptomatic | 3 years | Numerous, discrete, pinhead or half-rice corn-sized, and flesh-colored papules. No umbilication noted | None reported |

| Banse-Kupin et al9 | USA | 22 | Male | Ankle, forearms, trunk, thighs, penis | Asymptomatic | 1 month | Discrete, flesh-colored dome-shaped papules | None reported |

| Bardach1 | Austria | 8 | Male | Arms, trunk, legs, elbows, forearms, and knees | Asymptomatic | Few months | Multiple, discrete, pinpoint to pinhead, round and polygonal, flesh-colored, flat, and shiny papules | None reported |

We found that there is close correlation between clinical and dermoscopic structures and histologic findings in perforating LN. Macroscopically, lesions are 1-2 mm in size and are identified by their umbilicated and occasionally dome-shaped appearance, similar to molluscum contagiosum. In the present case, we observed pale-white papules with radial ridges emanating in a “sunburst” pattern from a depressed central keratotic core (Fig 1, C, black arrow). This corresponded to the sharply-circumscribed “ball-in-claw” dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate bounded by elongated rete ridges found in classic LN, but with a distinctive central transepidermal perforating channel extending through the stratum corneum, specific to perforating LN.

We describe for the first time, to our knowledge, the presence of a collarette of white scale in most lesions, which corresponded to parakeratosis at the focus of the perforating channel and pink lesions with linear or hairpin vessels, which corresponded to superficial elongated and ectatic vessels on histology (Fig 1, C, blue arrow). We show that neither collagen nor elastin is extruded through the transepidermal perforation. Finally, we provide dermoscopic images of perforating LN in the palms, revealing pale-white papules with central keratotic cores but without any visible surrounding vessels (Fig 1, F).

Based on the clinical appearance of these lesions, the differential diagnoses may include molluscum contagiosum, lichen spinulosus, or keratosis pilaris. However, perforating LN lesions tend to be smaller and less raised than molluscum and are non-follicular, thereby being distinguishable from these other entities. While transepidermal perforation is typically seen in primary perforating disorders such as Kyrle disease, elastosis perforans serpiginosa, and reactive perforating collagenosis, it also occurs secondary to other processes like granuloma annulare and lichen planus, among others.10 Perforating LN can be added as another example of a secondary perforating disorder. The pathogenesis is unclear, but we hypothesize that it may reflect an attempt to eliminate foreign or inflammatory material through the central perforating channel.

A review of the handful of previous cases (Table I) suggests that perforating LN typically affects children and young adults (age range, 8-35 years) and is male-predominant (8 of 11 cases, 73%).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Seven of 11 cases (64%) presented in darker-skinned individuals (phototype IV-VI); however, hypotheses regarding ethnic predisposition have not yet been elucidated. Most perforating LN lesions presented on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet, forearms, elbows, and knees, though genital and extensive truncal varieties have also been reported.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Additionally, 5 of the 11 cases (45%) described central umbilication, which differentiates these eruptions from the classically flat-topped or dome-shaped LN lesions. Perforating LN tends to respond well to topical steroids. Four of 6 cases with recorded treatment efforts, including ours, demonstrated lesional flattening or clearance as soon as several weeks of treatment initiation.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Perforating LN is an uncommon manifestation of an already rare condition. We highlight the clinical, dermoscopic, and histologic characteristics of perforating LN and reviewed previous reports of this entity. The identification of additional cases with this presentation will enable a better understanding of its etiology and further characterization of its pathophysiology and clinical course.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Bardach H. Perforating lichen nitidus. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8(2):111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1981.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li X.Q., Chen X., Li B. Dermoscopy of perforating lichen nitidus: a case report. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(17):2135–2136. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Mera C., Herrero-Moyano M., Capusan T.M., Renke A.U., Sánchez-Pérez J. Dermoscopy of a perforating lichen nitidus. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59(1):61–62. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zussman J., Smart C.N. Perforating lichen nitidus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(5):406–408. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijaya B., Sunila, Manjunath G.V. Perforating lichen nitidus. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53(1):162–163. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.59215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arrue I., Arregui M.A., Saracibar N., Soloeta R. Perforating lichen nitidus on an atypical site. Article in Spanish. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100(5):429–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon T.Y., Kim J.W., Kim M.K. Two cases of perforating lichen nitidus. J Dermatol. 2006;33(4):278–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itami A., Ando I., Kukita A. Perforating lichen nitidus. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33(5):382–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banse-Kupin L., Morales A., Kleinsmith D.A. Perforating lichen nitidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9(3):452–456. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah H., Tiwary A.K., Kumar P. Transepidermal elimination: historical evolution, pathogenesis and nosology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84(6):753–757. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_396_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]