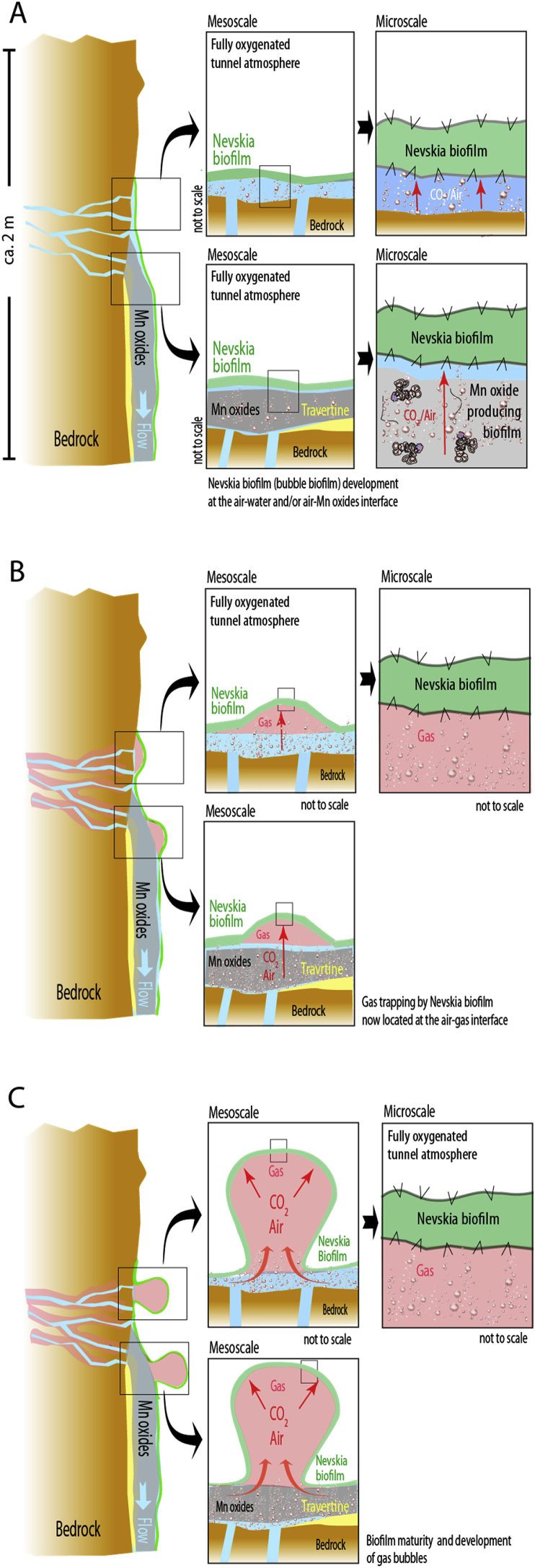

Fig. 4.

Model of bubble biofilm formation (A) Due to its partial hydrophobic nature, the Nevskia dominated biofilm colonize the air-water interface attached to bedrock surfaces, lithified calcium carbonate (travertine), or Mn precipitates. (B) Groundwater reaching the bedrock surface releases pockets of air that have been trapped inside the water bearing rock fractures and also equilibrates with the tunnel atmosphere which induces CO2 degassing. This gas diffuses through the Mn oxides but not through (or very slow diffusion) the Nevskia biofilm, contributing to formation of gas bubbles. (C) Gas build-up (increase in bubble size) occurs in periodic pulses. The bubble then remains stable for several months (no visible deflation but occasional growth pulses). Over time, the bubble migrate down the rock wall (the first bubble moves downward when a new bubble is formed) creating long chains or cluster of bubbles. Mechanical disruption of the biofilm during migration (from rolling down on an irregular substrate) occasionally leads to gas losses. Although Nevskia bacteria are situated at the air-air interface, the biofilm still holds sufficient water to sustain microbial activity and biofilm maturation.