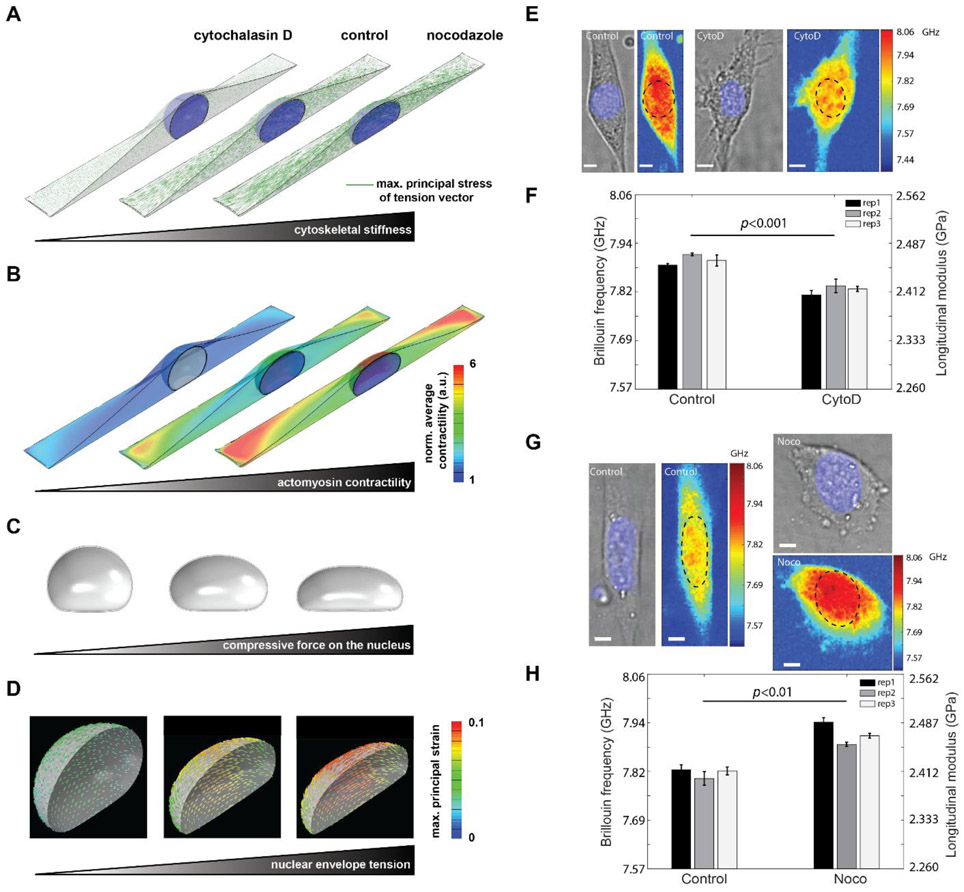

Figure 4. Regulation of intact nuclear moduli of attached cells by cytoskeletal modification.

Fibroblasts were simulated on a large rectangular fibronectin-coated micropatterned substrate with a surface area of 1600 μm2 and an aspect ratio of 1:5. Simulation results of (A) cytoskeletal stiffness. The green line indicates the maximum principal stress of the tenson vector at each location, and the length represents the amplitude of the stress. (B) actomyosin contractility. The value is normalized to the minimum value. a.u. arbitray unit. (C) compression force. (D) nuclear envelope tension. Our simulations show how disruption of cytoskeletal components (actin filaments and microtubules) upon treatment with CytoD and Nocodazole changes actomyosin contractility and cytoskeletal organizations and subsequently impacts nuclear morphology and the mechanical forces that the nucleus experience. (E) Representative cell images after CytoD treatment in experiment. Colormaps are corresponding Brillouin images. The dashed circle indicates the location of the nucleus. (F) Repeated results of nuclear Brillouin shifts after CytoD treatment in experiment. Colors indicate different experiments. The bar plots indicate the averaged Brillouin shift of the nucleus. The error bar is s.e.m. (G) Representative results of nuclear Brillouin shifts after Nocodazole treatment in experiment. (H) Repeated results of nuclear Brillouin shifts after Nocodazole treatment in experiment. The scale bar is 5μm, and the color bar has a unit of GHz. In each repeat, ≥ 6 cells were measured from both control and treated groups. Statistical significance is determined by the paired t-test of three repeats.