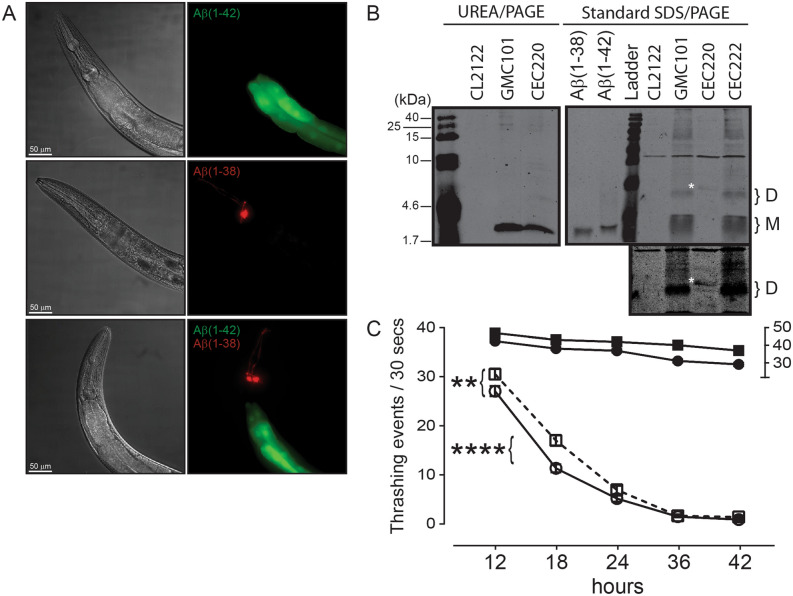

Figure 6.

Aβ(1–38) can partially suppress Aβ(1–42)-dependent muscle deterioration in C. elegans. (A) Representative images of the anterior region of worms overexpressing untagged Aβ peptides in body wall muscle. DIC images (left panels) and live fluorescence (right panels) represent: Aβ(1–42) (GMC101 strain; transgene marked by GFP (green) in the intestine), Aβ(1–38) (CEC220 strain; transgene marked by DsRed (red) in head neurons), and a double transgenic animal (CEC222 strain) expressing both Aβ(1–42) and Aβ1(-38) peptides (both green and red markers present). Scale bar, 50 μm; magnification, 50X. (B) Representative immunoblot of UREA/SDS-PAGE resolved extracts showing the expression of Aβ(1–42) in the GMC101 strain and Aβ(1–38) in the CEC220 strain. The protein ladder (in kDa) is indicated on the left. Extracts were also resolved by standard 15% SDS-PAGE and reveal putative monomers (M) and dimers (D). A band in the CEC220 extract (identified with white asterisk ‘*’) likely represents a modified Aβ(1–38) dimer, which is seen more clearly in a longer exposure (lower panel). (C) Time-dependent changes in the thrashing rates in CL2122 (control) worms (filled circle) and worms expressing Aβ(1–38) (filled square) (relative to the ‘30–50’ segment on the right Y-axis) as well as in the Aβ(1–42)-expressing GMC101 strain (○), and worms co-expressing Aβ(1–38) and Aβ(1–42) phenotype (□). Two-way ANOVA shows that all groups were significantly different from their respective control groups (n = 60–90; mean ± sem). **: P = 0.01; ****: P = 0.0001 between indicated groups.