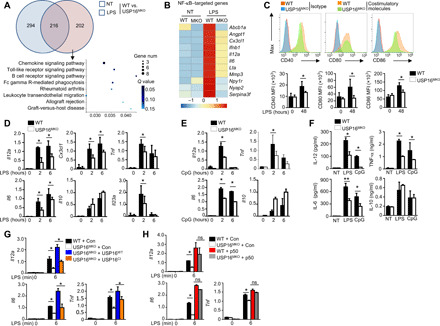

Fig. 5. USP16 is required for the induction of various NF-κB–targeted genes.

(A) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of DEGs between WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs under nontreatment or LPS-stimulated conditions for 6 hours. The KEGG analysis results of the enriched biological processes for these DEGs are shown. (B) Heatmap showing basal LPS-responsive (right) NF-κB–targeted genes among the DEGs of WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs. (C) Flow cytometry of the expression of CD40, CD80, and CD86 in WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs in response to LPS stimulation. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (D and E) qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA (vertical axes) in WT or USP16-deficient BMDMs unstimulated (0 hour) or stimulated for 2 or 6 hours with LPS (100 ng/ml) (D) or CpG (25 nM) (E). (F) ELISA results for the indicated cytokines in the supernatants of WT or USP16-deficient BMDMs stimulated with LPS for 12 and 24 hours. (G) qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated genes in USP16-deficient BMDMs reconstituted with USP16WT and USP16CI and subjected to LPS stimulation. (H) qRT-PCR analysis of proinflammatory cytokine production in WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs reconstituted with p50. All qRT-PCR data are presented as the fold induction relative to the Actb mRNA level. The data are presented as the means ± SEMs and are representative of at least three independent experiments. The statistical analysis results show the variations among experimental replicates. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. *P < 0.05.