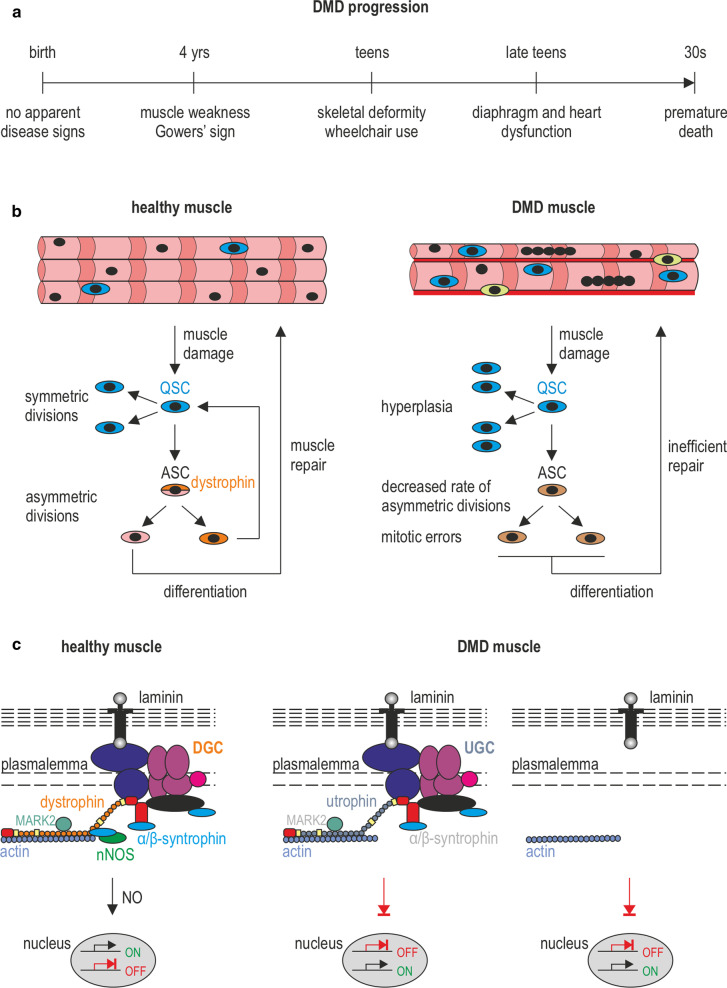

Fig. 1.

DMD—the disease of satellite cells and myofibers. a A timeline showing the progression of DMD symptoms. The affected boys develop motor skills until the age of 4–6, however, at a lower rate than their peers. Muscle weakness and Gowers’ sign are apparent from the age of 4. The condition of the muscles deteriorates quickly and the patients are forced to use a wheelchair in their teens. Typically, in the late teens, they need to start to use a temporary and then 24-h ventilation aid as a consequence of dysfunctional respiratory muscles. The boys die usually in their twenties/thirties, due to respiratory or cardiac failure. b In response to damage, QSCs (marked sky blue) that reside between the basal lamina and the plasmalemma, are activated and divide asymmetrically to generate SCs that return to the quiescent state (marked orange) and SCs undergoing differentiation into myoblasts that participate in muscle repair (marked pink). The asymmetric division is driven by dystrophin in combination with its binding partner, MARK2 (see in c). Lack of dystrophin leads to diminished levels of MARK2 and β-syntrophin in satellite cells (and α-syntrophin in skeletal muscle and NMJs), lower amounts of asymmetric divisions, and an increase in abnormal mitotic divisions. Also, note the elevated numbers of satellite cells in DMD muscles that are generated through symmetric divisions as well as increased fibrosis (marked red) and infiltration of immune cells (marked yellow). c DGC in the plasmalemma of satellite cells and myofibers performs structural and signal transduction functions, including those that pertain to NO production. In DMD muscles, the loss of dystrophin results in partial compensatory assembly of the utrophin-based complex (UGC) as well as other proteins and protein complexes (not shown). In neither case, the correct signal transduction functions are restored