Abstract

Purpose:

Bladder antimuscarinic (BAM) drug use is associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD). It is hypothesized that BAMs with non-selective receptor binding may increase ADRD risk more than M3-selective BAMs. This study compared ADRD risk for users of non-selective and M3-selective BAMs and examines ADRD risk associated with overall BAM use.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort study of Medicare claims for 71 688 individuals who used BAM drugs during 2007–2009 without an ADRD diagnosis. We compared ADRD incidence (2011–2016) between non-selective BAM users (fesoterodine, flavoxate, oxybutynin, tolterodine, trospium) and M3-selective BAM users (darifenacin, solifenacin). Logistic regressions compared individuals using target drugs in the same category of total standardized daily doses (TSDD) as a standardized measure of drug exposure, and adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, healthcare utilization, other medication use, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities. Secondary analyses compared ADRD risk associated with different doses of BAMs overall.

Results:

Non-selective BAM use (compared to M3-selective) was not significantly associated with ADRD incidence. Odds ratios for non-selective use were 0.97 (CI: 0.89–1.04) for 1–364 TSDD, 0.94 (CI: 0.83–1.06) for 365–729, 1.00 (CI: 0.87–1.16) for 730–1094, and 1.03 (CI: 0.88–1.20) for >1094. Higher TSDD of BAMs overall (combining both non-selective and M3-selective BAMs), when compared to 1–364 TSDD, were associated with increased ADRD incidence (OR = 1.05 (CI: 0.99–1.10) for 365–729, OR = 1.11 (CI: 1.05–1.17) for 730–1094, and OR = 1.10 (CI: 1.04–1.15) for >1094).

Conclusions:

Non-selective and M3-selective BAM users had similar odds of ADRD incidence, and BAM use overall was significantly associated with ADRD incidence.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease and related dementiasanticholinergics, bladder, antimuscarinics, pharmaco epidemiology

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) have a large, growing, and disparate burden on patients, their caregivers, and the health system overall. In the United States, there are approximately 7 million individuals aged 65 and older living with ADRD, and this number is projected to grow to 12 million by 2040.1 Efforts to alleviate this burden have included the identification of risk factors for ADRD, including prescription drugs such as anticholinergic medications. These medications are widely used by older adults for diverse conditions, including overactive bladder (OAB), seasonal allergies, and depression.2 Mounting evidence has linked anticholinergic medications to higher ADRD incidence.2–4

Bladder antimuscarinics (BAMs), used to treat OAB, have anticholinergic effects and are included in the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults.5 In addition to their reported link to incident dementia (studies have found at least 19% higher odds of dementia, compared to non-users),2–4,6,7 BAMs have also been linked to cognitive and functional decline.7–12 However, some studies did not find an association between BAM use and cognitive decline.13–17

All BAMs are similarly effective for OAB, but some hypotheses have suggested that certain BAMs may affect cognition less than others. The intended therapeutic effect of BAMs on OAB is thought to occur via blockage of M3 muscarinic receptors, and the possible negative side effects on cognition and ADRD risk are thought to occur via a simultaneous blockage of M1 receptors in the brain.8,11,13,14,18 It is therefore possible that some BAMs, which selectively bind to M3 receptors, and not M1 receptors, may exhibit comparatively less harmful effects on the brain.11,14,19 For example, while oxybutynin binds to both M3 and M1 receptors, darifenacin exhibits 9.3-times greater selectivity for M3 than M1 receptors.8 Therefore, hypothetically, oxybutynin (and other non-selective [NSL] BAMs) may have more harmful effects on cognition and ADRD incidence than darifenacin (and other M3-selective [M3S] BAMs). A few studies have compared cognitive outcomes across different types of BAMs,13,14 including a randomized trial that found worse memory impairment for NSL users than M3S after 3 weeks of followup.8 Some have examined ADRD incidence for subsets of BAM users as compared to nonusers, but without explicit comparisons of the different BAMs.6,7 To our knowledge, there are no existing studies that explicitly compare ADRD incidence between NSL and M3S BAM users.

In this study, we contrasted ADRD incidence between users of five NSL BAMs and two M3S BAMs, across comparable doses. Due to the disparate burden of ADRD across sex and race/ethnicity,20 and reported differences in pharmaceutical risk factors for ADRD for these subgroups,21,22 we separately analyzed these relationships across sex and race/ethnicity. With direct comparisons of NSL and M3S BAMs, and a 7 year follow-up period, we aim to contribute to understanding the ADRD risk associated with the use of different types of BAMs. This is an important research question because OAB occurs for 16%−17% of US adults and has significant negative effects on quality of life, including reduced daily activities, mental health, sleep quality, and sexual function.23 Despite increasing use of mirabegron (beta-3 agonist) for OAB, BAMs remain the most common treatment option,24,25 and it is critical to understand whether certain BAMs are safer with regards to ADRD risk.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Data

We examined the medical and pharmacy claims of a random 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in traditional Medicare (fee-for-service) from 2007 to 2016. We linked data on demographics, enrollment, vital status, and claims from Medicare Parts A, B, and D. Part D claims include information on prescription drug use, and Parts A and B cover inpatient and outpatient encounters, and include all diagnostic codes (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions [ICD-9 and ICD-10]). Specific diagnosis codes are shown in Appendix 1. Additional information on claims history was added from the Chronic Conditions Warehouse. Race/ethnicity was determined with the beneficiary race code in CMS enrollment data, and with the application of a name-based identification algorithm from the Research Triangle Institute.26

2.2 |. Study sample

The sample was composed entirely of Medicare beneficiaries using BAMs, with at least two BAM claims in one of the exposure period years (2007–2009), and at least 67 years old at the beginning of 2007. We required them to be enrolled in Medicare Part D from 2007 to 2009, in order to ensure that we observed all BAM use during the exposure period. Additionally, we required them to have fee-for-service Medicare from 2005 up through at least 2011. This ensures that we are able to observe any ADRD diagnoses, including those that may have occurred prior to the exposure period. Anyone with an ADRD diagnosis prior to 2011, or prior use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or memantine, was excluded. The analytic sample was composed of 71 667 individuals, of whom 56 773 (79%) were female, 61 381 (86%) were White, 4049 (6%) were Black, 3622 (5%) were Hispanic, and 2165 (3%) were Asian, Native American, or unknown race/ethnicity.

2.3 |. Measuring BAM exposure

We identified BAM users by selecting Part D claims (2007–2009) for five NSL BAM drugs (fesoterodine, flavoxate, oxybutynin, tolterodine, and trospium), and two M3S BAMs (darifenacin and solifenacin), which are the seven drugs indicated for OAB during our exposure period, and remain the most popular treatments for OAB.24,25 We measured use of NSL and M3S according to their total standardized daily doses (TSDD), which is calculated as an individual’s total dose for a year, divided by the minimum daily dose that is specific to the efficacy of that drug (fesoterodine 4 mg, flavoxate 300 mg, oxybutynin 3.9 mg for patch and 5 mg for oral, tolterodine 2 mg, and trospium 20 mg, darifenacin 7.5 mg, and solifenacin 5 mg).2 Individuals were divided into four exposure categories according to their TSDD of NSL and M3S BAMs: 1–364, 365–729, 730–1094, and greater than 1094 daily doses. These categories relate to an individual’s length of use, adherence, and condition severity, all of which increase TSDD. The categories were chosen because they correspond to years of exposure during our 3 year exposure period, and are each composed of sufficient sample size for sub-analyses defined by sex and race/ethnicity.

2.4 |. Study design

We used a retrospective cohort study design. Within each of the four aforementioned exposure categories, we compared ADRD incidence for NSL users and M3S users. By making comparisons between individuals who used different BAMs at similar categories of exposure, we are controlling for unobserved factors that differ between users and nonusers of BAMs, and for unobserved factors that differ across levels of BAM exposure. To ensure an appropriate temporal relationship between exposure and outcome, we measured BAM exposure from 2007 to 2009, imposed 2010 as a washout period, and assessed ADRD incidence during 2011–2016 (Figure 1). We required that no individuals were diagnosed with ADRD prior to 2011, and that all ADRD diagnoses from 2011 to 2016 had confirmation of the diagnosis in other claims (a second ADRD diagnosis code after the first). Any measurement error in the diagnosis of ADRD is unlikely to bias our results because the same error would exist for both NSL and M3S BAM users.

FIGURE 1.

Study design

As a secondary analysis, we evaluated the relationship between BAM use overall and ADRD incidence. These analyses compare people who used any BAMs at higher exposures (365–729, 730–1094, and greater than 1094 TSDD) to a reference group who used them at lower exposure (1–364 TSDD). The same exposure, washout, and outcome timings were used.

2.5 |. Statistical analyses

We used multivariable logistic regression to control for the following potential confounders, which were measured in the Medicare claims in 2009: age, age squared, sex, dual eligible (for both Medicare and Medicaid), Medicare low income subsidy, comorbidity index, number of physician visits, use of statins, use of antihypertensives, time between OAB diagnosis and BAM use, OAB-related diagnosis indicators (hypertonicity of bladder, neurogenic bladder, other functional disorder of the bladder, dysuria, urinary incontinence, urgency of urination, and frequency of urination and polyuria), and indicators for past diagnoses of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke. In addition to comorbidity indicators, we also included quartiles of the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Service Hierarchical Condition Category (CMS-HCC), an index based on diagnoses and demographics, in which higher numbers indicate worse health.27

3 |. RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the BAM users in our analytic sample. The unadjusted ADRD incidence during 2011–2016 was 3.97% per year for NSL BAM users, and 4.04% for M3S BAM users. The mean age for NSL users was 75.8 years, and 75.7 years for M3S users. NSL users were comprised of more females (80.1% vs 77.2% for M3S). Overall health status was similar for the two groups, with a mean comorbidity index of 1.19 for NSL, and 1.18 for M3S, and similar prevalence of atrial fibrillation, diabetes, stroke, acute myocardial infarction, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Diagnoses of specific types of over-active bladder varied between the two groups: hypertonicity (40.8% vs 47.1%), neurogenic bladder (11.0% vs 12.3%), other functional disorders of the bladder (11.0% v 12.3%), dysuria (47.8% vs 50.5%), urinary incontinence (80.6% vs 84.2%), frequency of urination and polyuria (69.1% vs 75.7%), and urgency of urination (28.2% vs 35.6%), for NSL and M3S, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of bladder antimuscarinic use

| All BAMs | Non-selective | M3-selective | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N with at least 1 TSDD | 71 668 | 60 114 | 24 436 |

| BAM total standardized daily doses (TSDD) 2007–2009 | |||

| Mean | 874 | 870 | 424 |

| SD | 761 | 779 | 454 |

| 25th% | 240 | 240 | 90 |

| 50th% | 660 | 630 | 240 |

| 75th% | 1350 | 1380 | 600 |

| 95th% | 2160 | 2190 | 1440 |

| N (%) with 1–364 TSDD | 25 830 (36%) | 22 629 (38%) | 15 235 (62%) |

| N (%) with 364–729 TSDD | 12 874 (18%) | 10 350 (17%) | 4533 (19%) |

| N (%) with 730–1094 TSDD | 10 289 (14%) | 8114 (13%) | 2545 (10%) |

| N (%) with >1094 TSDD | 22 674 (32%) | 19 021 (32%) | 2123 (9%) |

| Characteristics of individuals using BAMS (at least 1 TSDD) (%, unless otherwise noted) | |||

| ADRD annual incidence 2011–2016 | 3.95 | 3.97 | 4.04 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 75.8 (6.92) | 75.8 (6.93) | 75.7 (6.83) |

| Female | 79.2 | 80.1 | 77.2 |

| White | 85.6 | 85.8 | 85.9 |

| Black | 5.6 | 5.8 | 4.7 |

| Hispanic | 5.1 | 4.9 | 5.5 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.9 |

| Dual eligible | 31.8 | 31.8 | 31.0 |

| Low income subsidy | 8.8 | 8.7 | 8.8 |

| HCC (mean, SD) | 1.19 (0.87) | 1.19 (0.88) | 1.18 (0.86) |

| Physician visits in year (mean, SD) | 10.4 (8.28) | 10.3 (8.29) | 11.47 (8.65) |

| Hypertension | 83.9 | 83.9 | 83.5 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 75.8 | 75.5 | 76.8 |

| AMI | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 11.8 | 11.8 | 11.9 |

| Diabetes | 34.6 | 34.6 | 34.5 |

| Stroke | 14.2 | 14.1 | 14.4 |

| Hypertonicity | 41.1 | 40.8 | 47.1 |

| Neurogenic bladder | 10.8 | 11.0 | 12.3 |

| Other functional disorder of the bladder | 11.2 | 11.0 | 13.8 |

| Dysuria | 47.8 | 47.8 | 50.5 |

| Urinary incontinence | 80.5 | 80.6 | 84.2 |

| Frequency of urination and polyuria | 69.7 | 69.1 | 75.7 |

| Urgency of urination | 28.9 | 28.2 | 35.6 |

Note: Sample is Medicare beneficiaries who used BAMs (at least 2 claims) during 2007–2009, restricted to those with at least 3 consecutive years of FFS and Part D coverage, age 67+, no ADRD as of 2011, and no prior use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) or memantine. NSL BAMs are fesoterodine, flavoxate, oxybutynin, tolterodine, and trospium, and M3S BAMs are darifenacin and solifenacin. Abbreviations: ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; BAM, bladder antimuscarinic; FFS, fee-for-service; HCC, hierarchical condition category; M3S, M3-selective; OAB, overactive bladder; Other race/ethnicities, Asian, Native American, or unknown; NSL, non-selective; TSDD, total standardized daily doses.

Figure 2 depicts the adjusted odds ratios (OR), P values, and confidence intervals (CI) of the association between NSL BAM exposure (2007–2009) and ADRD incidence (2011–2016), as compared to individuals using M3S BAMs at the same category of exposure. These results show that NSL BAM use (compared to M3S) was not significantly associated with ADRD incidence. This was true at all four levels of exposure (1–364, 365–729, 730–1094, and >1094 TSDD), and for subsamples restricted to female, male, White, Black, and Hispanic individuals. Sensitivity analyses, reported in eTable 1, show that results were not influenced by switching between BAM types, selective attrition from the sample, dose variation within exposure categories, the presence of trospium, or dose outliers.

FIGURE 2.

Association between ADRD incidence and exposure to non-selective BAMs, as compared to M3-selective BAMs, within a consistent category of BAM exposure. Logistic regression results for ADRD incidence (2011–2016) as related to 2007–2009 exposure to BAM drugs. Each OR corresponds to a single regression that compares users of NSL BAMs with total daily doses in the noted range, to users of M3S BAMs in the same range. Sample is Medicare beneficiaries who used BAMs (at least two claims) during 2007–2009, restricted to those with at least 3 consecutive years of FFS and Part D coverage, age 67+, no ADRD as of 2011, and no prior use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) or memantine. NSL BAMs are fesoterodine, flavoxate, oxybutynin, tolterodine, and trospium, and M3S BAMs are darifenacin and solifenacin. Controls are age, age squared, sex, dual eligible, low income subsidy, HCC comorbidity index, number of physician visits, use of statins, use of antihypertensives, time between OAB diagnosis and BAM use, OAB-related diagnosis indicators (hypertonicity of bladder, neurogenic bladder, other functional disorder of the bladder, dysuria, urinary incontinence, urgency of urination, and frequency of urination and polyuria), and indicators for past diagnoses of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke. Standard errors are clustered at the county level. ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; BAM, bladder antimuscarinic; CI, 95% confidence interval; FFS, fee-for-service; HCC, hierarchical condition category; M3S, M3-selective; NSL, non-selective; OAB, overactive bladder; OR, odds ratio; TSDD, total standardized daily doses

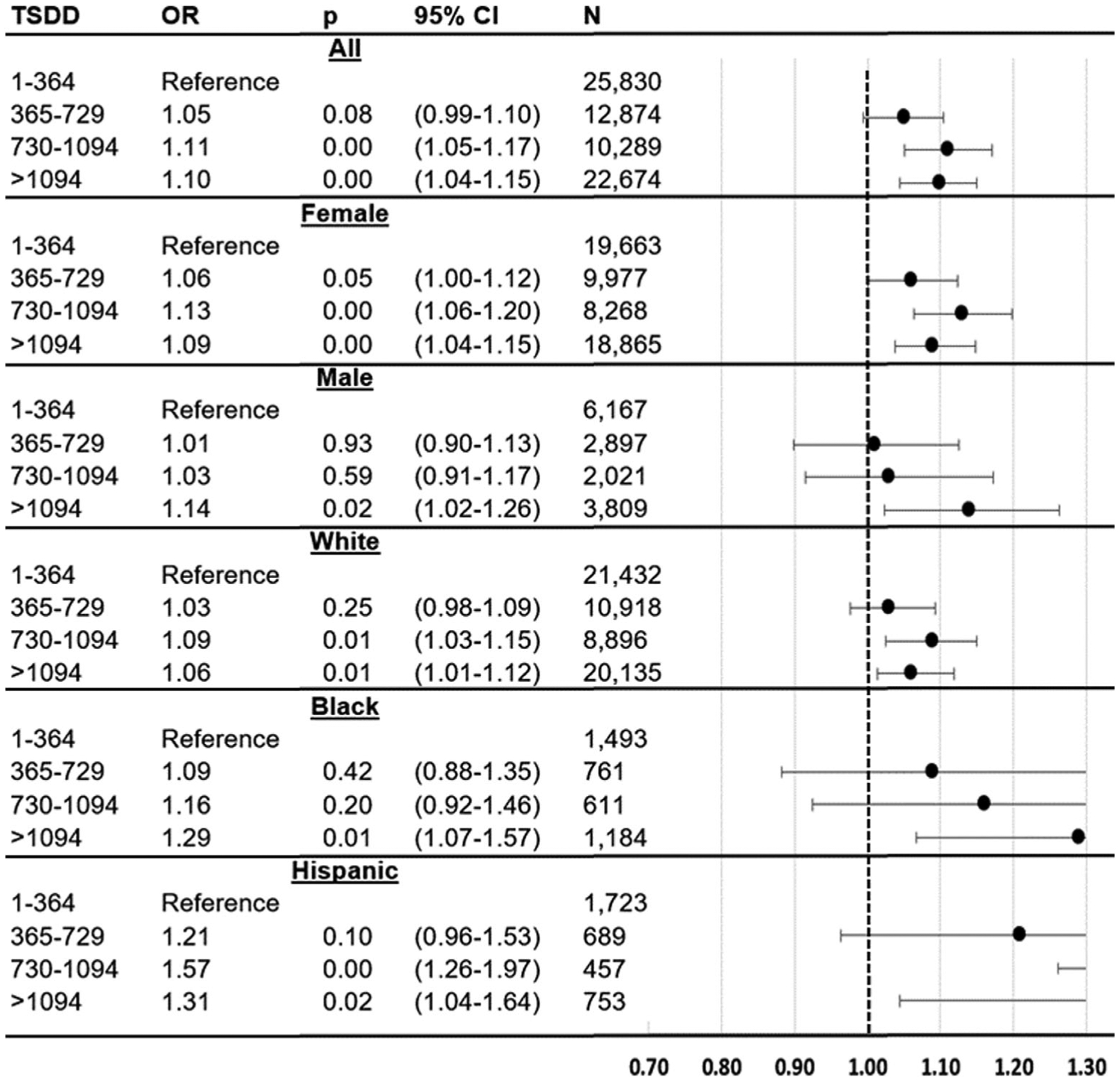

Figure 3 shows the adjusted ORs from secondary analyses, which examined the association between use of any BAM and ADRD incidence, across levels of BAM exposure, with 1–364 TSDD as the reference group. These results show that higher levels of BAM exposure are significantly associated with higher odds of ADRD incidence (365–729 TSDD OR = 1.05, CI = 0.99–1.10; 730–1094 OR = 1.11, CI = 1.05–1.17; >1094 OR = 1.10, CI = 1.04–1.15). The characteristics of individuals in these TSDD categories are reported in eTable 2. The associations varied across subsamples defined by race/ethnicity, with higher doses associated with greater odds of ADRD in Hispanics compared with Whites (Whites: 365–729 OR = 1.03, CI = 0.98–1.09; 730–1094 OR = 1.09, CI = 1.03–1.15; >1094 OR = 1.06, CI = 1.01–1.12; Hispanics: 365–729 OR = 1.21, CI = 0.96–1.53; 730–1094 OR = 1.57, CI = 1.26–1.97; >1094 OR = 1.31, CI = 1.04–1.64).

FIGURE 3.

Association between ADRD incidence and categories of total standardized daily doses (TSDD) of any BAM, across categories of BAM exposure. Logistic regression results for ADRD incidence (2011–2016) as related to 2007–2009 exposure to BAM drugs. The figure shows results from six regressions, each of which relates TSDD of BAMs (365–729, 730–1094, >1094) to ADRD incidence, as compared to individuals using 1–364 TSDD. Sample is Medicare beneficiaries who used BAMs (at least 2 claims) during 2007–2009, restricted to those with at least 3 consecutive years of FFS and Part D coverage, age 67+, no ADRD as of 2011, and no prior use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) or memantine. BAMs are fesoterodine, flavoxate, oxybutynin, tolterodine, trospium, darifenacin, and solifenacin. Controls are age, age squared, sex, dual eligible, low income subsidy, HCC comorbidity index, number of physician visits, use of statins, use of antihypertensives, time between OAB diagnosis and BAM use, OAB-related diagnosis indicators (hypertonicity of bladder, neurogenic bladder, other functional disorder of the bladder, dysuria, urinary incontinence, urgency of urination, and frequency of urination and polyuria), and indicators for past diagnoses of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke. Standard errors are clustered at the county level. ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; BAM, bladder antimuscarinic; CI, 95% confidence interval; FFS, fee-for-service; HCC, hierarchical condition category; M3S, M3-selective; NSL, non-selective; OAB, overactive bladder; OR, odds ratio; TSDD, total standardized daily doses

4 |. DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine differences in ADRD by type of BAM in a large US cohort. We found no significant differences in ADRD incidence between NSL and M3S BAM users; these results were consistent in analyses by sex and race/ethnicity. Our study design compared individuals using two types of BAMs at similar doses, and has inherent advantages over study designs that include non-users, whose unobservable characteristics may predispose them to differential rates of ADRD, making them less appropriate comparators. Furthermore, NSL and M3S users had similar socioeconomic status (dual eligibility and low income subsidy status) and comorbidities (Table 1), which gives confidence that these factors are not confounding the analyses. Secondary analyses examined if ADRD varied across TSDD of all BAMs, and found that users with greater exposure to any BAM (more than 2 years) had significantly higher ADRD incidence than users with less than a year of total exposure. This implies that while the use of BAMs in general is a risk factor for ADRD, there is not a significant difference in this association between M3S and NSL BAMs.

These results fit into the broader literature on the relationship between anticholinergic medications and ADRD risk. Prior work hypothesized that some BAMs, which selectively bind to M3 receptors (M3S BAMs), may be less harmful with regards to ADRD risk, because of less blockage of M1 receptors in the brain.8,11,13,14,18,19 Our results do not support a comparative difference in ADRD risk. One possible reason might be that muscarinic selectivity is not binary—that is, the drugs categorized as M3S still have some activity with the M1 receptors,8 and that activity, even though it is weaker than NSL drugs, may still be strong enough to be harmful with regards to ADRD. Another factor that might lessen the importance of the distinction between NSL and M3S BAMs as it relates to effects on the central nervous system is the ability for drugs to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB).19 Individuals with OAB are more likely to have increased BBB permeability, meaning that passive crossing of the BBB could be an important component of the observed association between all BAMs and ADRD incidence.19 In general, age-related changes make older adults more sensitive to anticholinergic effects,2 and thus further reduce the importance of the distinction in selectivity between the two subtypes of BAMs. In addition to increased BBB permeability, these changes include age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and reductions in acetylcholine-mediated transmission in the brain.2,28 The American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria has listed both M3S and NSL BAMs as potentially inappropriate medications for older adults5; our results support this designation.

Our secondary analyses confirmed prior work showing the harmful association of BAMs overall, with much higher TSDD of a composite measure of BAMs associated with greater onset of ADRD, as compared to users with lower TSDD. Moderate doses (365–729 TSDD), were not associated with ADRD incidence in either sex, and for males, only doses greater than 1094 TSDD were associated with ADRD incidence. While most prior work compared BAM users to non-users, our study makes an important contribution by showing that this relationship exists in a sample composed entirely of BAM users. The magnitude of the association in our work was lower than prior studies, but this is not surprising, given that the earlier research used non-users as a comparison group.2–4 Individuals with higher TSDD are more likely to be female, White, have worse comorbidity scores, and be diagnosed with hypertonicity, neurogenic bladder, other functional disorder of the bladder, and urinary incontinence; all of these factors were controlled for in all analyses. The lack of differences in results across sex is consistent with prior studies.2,3 Interestingly, the association of BAM use and ADRD incidence increased more at higher doses for Hispanics than Whites. It is not clear why this was the case; future research in this area should examine effect heterogeneity across racial/ethnic groups.

Our study has limitations. The Medicare claims data are an excellent source of information on prescription drug utilization and medical diagnoses, but have certain shortcomings. ADRD diagnoses are imprecise, and their timing in claims data does not necessarily reflect the true onset of the condition. However, this does not bias our analyses, because there is no reason to believe that this measurement error would occur differently between our comparison groups. Another limitation is that prescription drug utilization data is only available back to 2006, when Medicare Part D was enacted. Therefore, we do not know when individuals began their BAM therapy. To control for this, we included a covariate in the regression for the length of time that passed between the first observed OAB diagnosis (as far back as 2002), and the first observed BAM use. This covariate, however, does not address the possibility that certain BAMs that were available earlier may have been used differentially during this unobservable period, therefore introducing bias. Another possibility is that individuals may use both NSL and M3S BAMs during the exposure period, which would obscure differences in ADRD risk. To adjust for this, we included a sensitivity analysis with the sample restricted to individuals who only used one type of BAM. These results are reported in eTable 1, and show no meaningful differences in results from the main analyses.

Another important consideration is unobservable factors influencing individuals to use one of type of BAMs, while also affecting their ADRD risk. Indeed, there is evidence that choice of BAM is related to patient characteristics, including that M3S BAMs are less likely to be used by individuals with moderate to severe cognitive performance29,30; our results show no difference in ADRD risk, suggesting that this selection of BAMs did not bias our analyses. Nevertheless, we included covariates to control for some of these factors (comorbidity index), and we imposed sample restrictions to ensure that individuals showed no signs of cognitive decline prior to the outcome period (2011–2016). This included the washout period requirement (no ADRD diagnoses prior to 2011), and requiring no observed use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or memantine during the exposure period, as these drugs are sometimes prescribed prior to ADRD diagnoses.31 We controlled for other factors that may influence both drug use and ADRD risk, such as socioeconomic status. OAB subtypes have different prevalence in M3S and NSL users (Table 1); we therefore control for these diagnoses in all analyses. We also acknowledge the increase in ADRD risk from use of all BAMs was relatively small (Figure 3), which makes it harder to rule out potential confounding.

It is also possible that selective attrition could affect our sample, if, for example, either NSL or M3S users were more likely to die or switch into Medicare Advantage, in which case ADRD diagnoses would not be observable. We addressed this in a sensitivity analysis with our sample restricted to individuals who had full observability up through 2016, or until their ADRD diagnosis date (results in eTable 1). Other sensitivity analyses included an additional control for BAM TSDD (to control for differences in BAM use within the specified TSDD categories), dropping trospium (based on the suggestion that it is less harmful than other NSL BAMs because it does not cross the BBB16), and dropping outliers (people who filled more than 365 days during a single year). These results are reported in eTable 1, and show no meaningful differences from the main analyses.

In conclusion, this study compared ADRD risk between users of different types of BAMs. Despite some hypotheses suggesting that M3-selective BAMs could be less harmful regarding ADRD risk than non-selective BAMs, our analyses that made a direct comparison of individuals using the two types of BAMs at similar doses found no difference in ADRD risk between the two groups. Our findings build on earlier work, by confirming that for older adults with OAB, BAM use overall is associated with ADRD risk, and should be used with caution. Future work should examine sources of heterogeneity in these relationships across race/ethnicity, and develop interventions to reduce the use of BAMs while maintaining bladder health.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Bladder antimuscarinic prescription drugs are associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD)

Prior work has hypothesized that some of these drugs, which selectively bind to M3-receptors, may be less harmful for brain health than non-selective bladder antimuscarinics.

We compared ADRD risk for users of M3-selective and non-selective bladder antimuscarinics, using Medicare claims data.

We found no significant difference in ADRD risk between users of non-selective and M3-selective bladder antimuscarinics.

Bladder antimuscarinics as a single class were associated with increased odds of ADRD incidence, confirming that these drugs should be used with caution.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Douglas Barthold is supported by NHLBI R01HL126804, Kaiser/NIH R01HL130462, NIH R01MH121424-01A1, NHLBI-1OT3HL152448-01

ZA Marcum was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (K76AG059929). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Shelly L. Gray receives support from the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01 AG056326, U01 AG006781, and R01 NS099129) as well as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant number U01CE002967).

Julie Zissimopoulos is supported by NIH grants R01AG055401 and P30AG043073.

Funding information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Grant/Award Number: U01CE002967; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant/Award Numbers: 1OT3HL152448-01, R01HL126804; National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: K76AG059929; National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: P30AG043073, R01 AG056326, R01 NS099129, R01AG055401, R01HL130462, R01MH121424-01A1, U01 AG006781

ETHICS STATEMENT

Institutional Review Board approval was granted by the University of Southern California University Park IRB.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zissimopoulos JM, Tysinger BC, Stclair PA, Crimmins EM. The impact of changes in population health and mortality on future prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in the United States. J Gerontol Series B. 2018;73(suppl 1):S38–S47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):401–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coupland CA, Hill T, Dening T, Morriss R, Moore M, Hippisley-Cox J. Anticholinergic drug exposure and the risk of dementia: a nested case-control study. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson K, Fox C, Maidment I, et al. Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study. BMJ. 2018;361:k1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Geriatric Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American geriatrics society updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4): 616–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Y-W, Liu H-H, Lin T-H, Chuang H-Y, Hsieh T. Association between different anticholinergic drugs and subsequent dementia risk in patients with diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moga DC, Abner EL, Wu Q, Jicha GA. Bladder antimuscarinics and cognitive decline in elderly patients. Alzheimer’s Demen Transl Res Clin Intervent. 2017;3(1):139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay G, Crook T, Rekeda L, et al. Differential effects of the antimuscarinic agents darifenacin and oxybutynin ER on memory in older subjects. Eur Urol. 2006;50(2):317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sink KM, Thomas J III, Xu H, Craig B, Kritchevsky S, Sands LP. Dual use of bladder anticholinergics and cholinesterase inhibitors: longterm functional and cognitive outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5): 847–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheife R, Takeda M. Central nervous system safety of anticholinergic drugs for the treatment of overactive bladder in the elderly. Clin Ther. 2005;27(2):144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glavind K, Chancellor M. Antimuscarinics for the treatment of overactive bladder: understanding the role of muscarinic subtype selectivity. Int UrogynecolJ. 2011;22(8):907–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Çetinel B, Onal B. Rationale for the use of anticholinergic agents in overactive bladder with regard to central nervous system and cardiovascular system side effects. Korean J Urol. 2013;54(12): 806–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagoria D, O’Connor RC, Guralnick ML. Antimuscarinic drugs: review of the cognitive impact when used to treat overactive bladder in elderly patients. Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12(5):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagg A, Verdejo C, Molander U. Review of cognitive impairment with antimuscarinic agents in elderly patients with overactive bladder. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(9):1279–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moga DC, Carnahan RM, Lund BC, et al. Risks and benefits of bladder antimuscarinics among elderly residents of veterans affairs community living centers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(10):749–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geller EJ, Dumond JB, Bowling JM, et al. Effect of trospium chloride on cognitive function in women aged 50 and older: a randomized trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(2):118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosilov K, Kuzina I, Loparev S, Gainullina Y, Kosilova L, Prokofyeva A. Influence of the short-term intake of high doses of solifenacin and trospium on cognitive function and health-related quality of life in older women with urinary incontinence. Int Neurourol J. 2018;22(1): 41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay GG, Abou-Donia MB, Messer WS Jr, Murphy DG, Tsao JW, Ouslander JG. Antimuscarinic drugs for overactive bladder and their potential effects on cognitive function in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2195–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chancellor MB, Staskin DR, Kay GG, Sandage BW, Oefelein MG, Tsao JW. Blood-brain barrier permeation and efflux exclusion of anticholinergics used in the treatment of overactive bladder. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(4):259–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321–387. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barthold D, Joyce G, Wharton W, Kehoe P, Zissimopoulos J. The association of multiple anti-hypertensive medication classes with Alzheimer’s disease incidence across sex, race, and ethnicity. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zissimopoulos JM, Barthold D, Brinton RD, Joyce G. Sex and race differences in the association between statin use and the incidence of Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(2):225–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eapen RS, Radomski SB. Review of the epidemiology of overactive bladder. Res Reports Urol. 2016;8:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldman HB, Anger JT, Esinduy CB, et al. Real-world patterns of care for the overactive bladder syndrome in the United States. Urology. 2016;87:64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linder BJ, Gebhart JB, Elliott DS, Van Houten HK, Sangaralingham LR, Habermann EB. National Patterns of filled prescriptions and third-line treatment utilization for privately insured women with overactive bladder. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019; Publish Ahead of Print. 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonito A, Bann C, Eicheldinger C, Carpenter L. Creation of New Race-Ethnicity Codes and Socioeconomic Status (SES) Indicators for Medicare Beneficiaries. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P, Kim MM, Doshi JA. Comparison of the performance of the CMS hierarchical condition category (CMS-HCC) risk adjuster with the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity measures in predicting mortality. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell N, Boustani M, Limbil T, et al. The cognitive impact of anticholinergics: a clinical review. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moga DC, Wu Q, Doshi P, Goodin AJ. An investigation of factors predicting the type of bladder antimuscarinics initiated in Medicare nursing homes residents. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vouri SM, Schootman M, Strope SA, Birge SJ, Olsen MA. Differential prescribing of antimuscarinic agents in older adults with cognitive impairment. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(4):321–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, Drabo EF, Marcum ZA, Gray SL, Zissimopoulos J. “Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities,” J Alzheimer’s Dis, forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.