Tuberculosis is the world's leading infectious cause of death, claiming at least 500 000 more lives than COVID-19 in 2020.1 The COVID-19 pandemic has irrevocably damaged tuberculosis care and will cause an excess 6 million tuberculosis cases by 2025. How can tuberculosis control possibly benefit from the varied and flawed public health response to COVID-19?

Early and widespread face-mask wearing could have prevented the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from becoming a pandemic.2 Face masks were initially recommended for outward protection to prevent transmission from infectious individuals. Following a review that also showed inward protection (ie, for the wearer), WHO recommended use of face masks by the public.3

Historically, public mask-wearing to prevent tuberculosis transmission met scepticism and low uptake due to stigma, restricted access, discomfort, and perceived liberty deprivation—similar barriers to those faced by condom uptake for HIV prevention.4 However, whereas condom acceptance improved, mask adoption to reduce tuberculosis transmission stagnated, even among patients with a positive test result, and mask wearing was often seen as an embarrassing public declaration of ill health. In a pre-COVID-19 survey we did in 100 patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis in Cape Town, South Africa, who were likely to be infectious, only 2% reported wearing surgical masks in shops. This proportion was similar to that of patients who reported wearing masks on public transport.

The pandemic could have created a momentum of mask acceptance beneficial for tuberculosis control. For example, in South Africa, public face masks have been mandatory for more than 6 months. If acceptance of masks can be maintained, it could be a game changer for tuberculosis control in high-burden countries—provided there is evidence that the masks used to protect from SARS-CoV-2 also reduce the infectiousness of tuberculosis, particularly the non-conventional forms such as cloth masks.

Unlike SARS-CoV-2, Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission is almost exclusively airborne. When wearing a mask, air can still pass through the gaps between mask and face.5 Although minimising these gaps is crucial for inward protection, Richard Riley, who confirmed the airborne nature of M tuberculosis transmission, is unconcerned about these leaks from an outward-protection perspective. He believes even simple cough etiquette should be effective because organisms leaving the mouth are still in droplets, which have not evaporated to droplet nuclei and are still large enough to impinge on an obstructing surface, such as the hand, and remain there.6 Data supporting Riley's view are sparse, but wearing a mask should act as a form of cough etiquette that is at least as effective as hands are.

In 2015, we seated patients with cystic fibrosis inside large cylindrical tanks and mixed air homogeneously to capture airborne particles, including those that escape through mask gaps. During coughing, surgical masks reduced airborne, culturable Pseudomonas aeruginosa by 88% (95% CI 81–96).7 M tuberculosis and P aeruginosa are similar in size but both are much larger than viruses. However, mask–pathogen interactions depend mainly on particle and not pathogen size (ie, the particles carrying viruses or bacteria might have similar sizes).8 In 2018, Michelle Wood and colleagues validated our P aeruginosa findings with another aerosol platform.9 Few studies have directly examined the effect of surgical masks on the infectiousness of tuberculosis; Ashwin Dharmadhikari and colleagues reported that 56% (95% CI 33–71) fewer guinea pigs were infected when they were exposed to air from inpatients on days those inpatients were encouraged to wear masks.10

To help policy makers decide whether public face-mask usage should be maintained for tuberculosis control as the COVID-19 pandemic wanes, more data are needed on the effect of masks on reducing the infectiousness of patients with tuberculosis. In July, 2018, we started recruiting patients with tuberculosis in Cape Town to study the effect of face masks (including non-conventional forms) using our aerosol platform. Pilot results, obtained before the study was paused because of the pandemic response measures, indicated that surgical masks are effective and that non-conventional and less stigmatising mask designs (eg, neck gaiters) and cheaper forms (eg, paper masks) are efficacious. It will take more than a year until conclusive data are published. However, public mask-wearing fatigue, unless it is urgently addressed, could close this rare window afforded by the COVID-19 response.

Mathematical modelling of the COVID-19 and tuberculosis epidemics in China, India, and South Africa, which did not factor in the effect of masks deployed for SARS-CoV-2 on tuberculosis transmission, suggests that reducing contacts by physical distancing would lead to population-level reductions in tuberculosis transmission and incidence, but also that these benefits would be offset by health service disruptions, resulting in net increases in tuberculosis cases and deaths.11 Hence, with the restoration of critical tuberculosis health-care services and economic activity as part of the post-COVID-19 recovery, policies for sustained mask-wearing could help turn the tide against tuberculosis. However, this proposal will require formal modelling.

Notably, the widespread public face-mask usage for SARS-CoV-2 partly stemmed from concerns about presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission. Half of the prevalent cases of bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis are probably subclinical (ie, symptom screen is negative).12 Whether such patients can transmit tuberculosis is not yet confirmed but is probably the case: a study in symptomatic patients found those with lower symptom scores to be more infectious.13 Therefore, the rationale for public mask usage against presymptomatic and asymptomatic spread of SARS-CoV-2 might also apply to tuberculosis spread. Another consideration is that improper mask hygiene and fomite risk, which could be downsides of mask usage for SARS-CoV-2, are not a concern for tuberculosis due to its almost exclusively airborne transmission route.

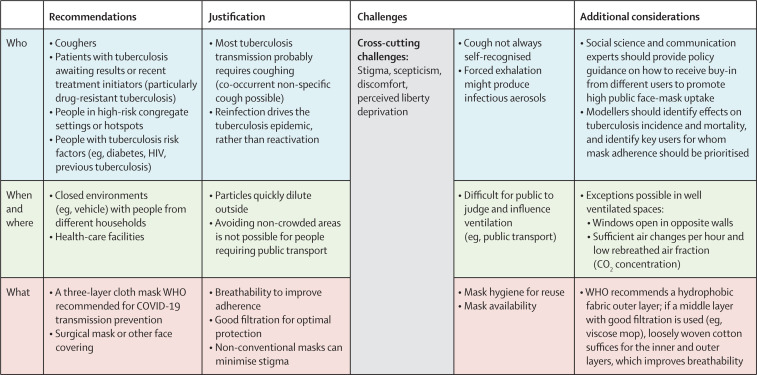

Although face masks vary in breathability and filtration characteristics, a good-quality cloth mask could be as effective as a surgical mask,14, 15 including for tuberculosis. Tuberculosis-endemic countries need to decide who should wear masks, and the times or places they should wear them (figure ). As a first step, cloth masks should be available outside of clinics for patients with tuberculosis awaiting diagnostic investigation and, in high-burden settings, for people with tuberculosis risk factors. Population-level mask-wearing should tackle any re-emergence of stigma. Because airborne particles disappear quickly outside, face masks should be prioritised for indoor use.

Figure.

Proposed face-mask recommendations that build on COVID-19 policies in tuberculosis-endemic countries

Suggestions and explanations are listed for who should wear masks, when they should wear them, where they should wear them, and the type of mask that should be considered.

In conclusion, although tuberculosis care is critically weakened by the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an unprecedented opportunity to throw masks into the fight against the long-standing tuberculosis pandemic. Although available data are sparse, which is something we are addressing, they suggest face masks, including non-conventional forms, can reduce the infectiousness of patients with tuberculosis. High tuberculosis transmission settings must retain mask-wearing as the COVID-19 pandemic wanes and pivot and protect the widespread public acceptance of face masks towards tuberculosis control.

© 2021 Garo/Phanie/Science Photo Library

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com/respiratory on October 26, 2021

Acknowledgments

We thank Greet Kerckhofs and Ben Marais for their valuable input and discussions. KVD and PZM contributed equally, as did HM and GT. We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Cilloni L, Fu H, Vesga JF, et al. The potential impact of the COVID-19 response on tuberculosis in high-burden countries: a modelling analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang R, Li Y, Zhang AL, Wang Y, Molina MJ. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:14857–14863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009637117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395:1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard J, Huang A, Li Z, et al. An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014564118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang JW, Nicolle AD, Pantelic J, et al. Qualitative real-time schlieren and shadowgraph imaging of human exhaled airflows: an aid to aerosol infection control. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley RL. Airborne infection. Am J Med. 1974;57:466–475. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanden Driessche K, Hens N, Tilley P, et al. Surgical masks reduce airborne spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in colonized patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:897–899. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0481LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fennelly KP. Particle sizes of infectious aerosols: implications for infection control. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:914–924. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood ME, Stockwell RE, Johnson GR, et al. Face masks and cough etiquette reduce the cough aerosol concentration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in people with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:348–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201707-1457OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dharmadhikari AS, Mphahlele M, Stoltz A, et al. Surgical face masks worn by patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: impact on infectivity of air on a hospital ward. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1104–1109. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1190OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQuaid CF, McCreesh N, Read JM, et al. The potential impact of COVID-19-related disruption on tuberculosis burden. Eur Respir J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01718-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frascella B, Richards AS, Sossen B, et al. Subclinical tuberculosis disease—a review and analysis of prevalence surveys to inform definitions, burden, associations and screening methodology. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1402. published online Sept 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theron G, Limberis J, Venter R, et al. Bacterial and host determinants of cough aerosol culture positivity in patients with drug-resistant versus drug-susceptible tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2020;26:1435–1443. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0940-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer EP, Fischer MC, Grass D, Henrion I, Warren WS, Westman E. Low-cost measurement of face mask efficacy for filtering expelled droplets during speech. Sci Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clase CM, Fu EL, Ashur A, et al. Forgotten technology in the COVID-19 pandemic: filtration properties of cloth and cloth masks—a narrative review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:2204–2224. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]