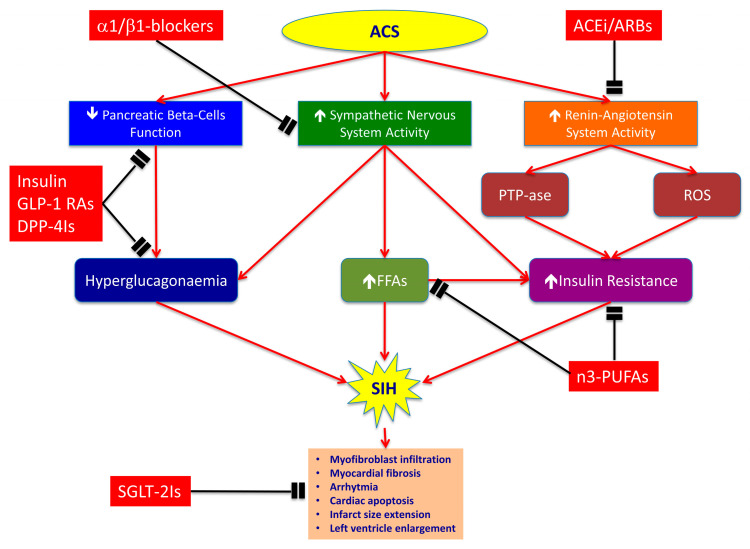

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of stress-induced hyperglycaemia (SIH) during acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and complementary effects of each pharmacological class. ACS determines SIH by decreasing insulin release through pancreatic beta-cells dysfunction, and by inducing insulin resistance (IR) through overactivation of sympathetic nervous and renin-angiotensin systems. The insulin decrease and adrenergic overdrive provoke hyperglucagonaemia and increase of free fatty acids (FFAs) plasmatic levels, thereby leading to hyperglycaemia. Contemporarily, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system hyper-stimulation induces IR through the activation of phosphotyrosine phosphatases (PTPases) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation. Selective α1/β1-blockers, such as nebivolol, antagonize adrenergic overdrive and have vasodilatory properties that are mediated by stimulation of nitric oxide (NO) release from endothelial cells. ACE inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) inhibit PTPases activity and ROS formation, thereby reducing IR. The n3-polyunsaturated fatty acids (n3-PUFAs) improve cholesterol levels and insulin sensitivity compared to diets high in saturated fats. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4Is) and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) improve pancreatic beta-cells function and reduce glucagon release by alfa-cells, thereby lowering HbA1c levels. Finally, sodium-glucose co-transporters 2 inhibitors (SGLT-2Is) have cardiovascular benefits mostly unrelated to the extent of glucose lowering. They could involve effects on haemodynamic parameters, such as reduced plasma volume, and direct effects on cardiac metabolism and function, such as myocardial fibrosis, cardiac apoptosis and infarct size enlargement. Red lines indicate activation pathways; black lines indicate inhibition pathways; ↑indicates an increase; ↓indicates a decrease.