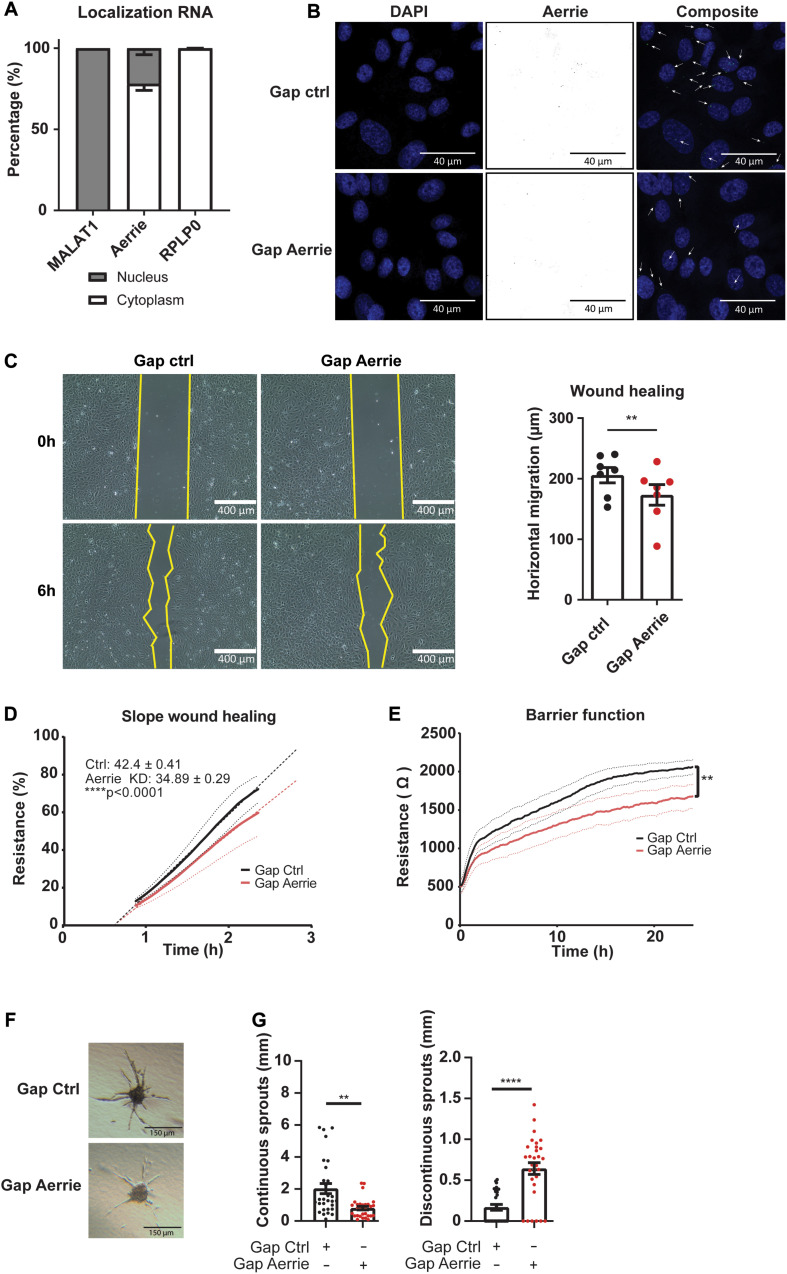

FIGURE 2.

The loss of Aerrie reduces migration, barrier function, and angiogenic sprouting in vitro. (A) HUVECs were fractionated into nucleus and cytoplasm. RT-qPCR was performed to measure lncRNA Aerrie localization. RPLP0 was used as cytoplasmatic control and lncRNA Malat1 as a nuclear control (n = 3). (B–G) HUVECs were treated with gapmeR (gap) targeting Aerrie or a respective control. (B) Subcellular localization of Aerrie in HUVECs was analyzed by SCRINSHOT RNA FISH. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI. Arrows indicate Aerrie localization. HUVECS were visualized with DAPI on the 405 nm channel and Aerrie on the 488 nm channel. (C) Scratch assay was performed with HUVECs for 6 h. The horizontal migration is calculated by the change in surface area (n = 7). (D) Electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) was performed to measure migration of HUVECs. The endothelial monolayer was damaged through lethal electroporation. The recovery slope was determined between 1 to 2 h post wounding (n = 3). (E) ECIS was performed to measure the barrier function of the endothelial monolayer. The resistance of the endothelial monolayer was determined after 24 h (n = 3). (F) Brightfield images of silenced Aerrie sprouts and its control. (G) Cumulative sprout length was determined for continuous and discontinuous sprouts. (n = 3, at least 10 spheroids were measured per experiment). Quantification of the discontinuous sprouts measured by the distance from the tip cell to the stalk cell. **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant.