Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in stay-at-home orders, which presented a significant challenge to the design and operation of an essential harm-reduction strategy in the opioid epidemic: community-based, take-home naloxone (THN) programs. This commentary describes how four rural and/or Appalachian communities quickly pivoted their existing THN programs to respond to community need. These pivots, which reflect both the context of each community and the capacities of its service delivery and technology platforms, resulted in enhancements to THN training and distribution that have maintained or expanded the reach of their efforts. Additionally, all four community pivots are both highly sustainable and transferrable to other communities planning to or currently implementing THN training and distribution programs.

Keywords: Overdose, Take-home naloxone, COVID-19, Rural health, Harm reduction, People who use drugs

A key impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been that more than 40 states are reporting increases in opioid-related mortality (Blaney-Koen, 2020). At the same time that mortality has been increasing, extended stay-at-home orders in most states and new norms related to social distancing and the size of mass gatherings have presented a significant challenge to the design and operation of community-based take-home naloxone (THN) programs, which are an essential harm-reduction strategy in the opioid epidemic. In this commentary, we explore how four rural and/or Appalachian community-based coalitions/opiate task forces in Ohio pivoted their existing THN programs due to the COVID-19 pandemic and how the modifications both enhanced and expanded their existing THN programs. These modifications were born out of necessity but will have lasting, positive implications for THN programs in these four communities and other communities can replicate them.

Medical professionals' opioid prescribing and opioid overdoses have increased significantly in the United States over the last twenty years (Strickler et al., 2020). In 2018, 67,367 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States, with opioids being responsible for almost 70% of those drug overdose deaths (Hedegaard et al., 2020). While rates of drug overdose deaths were higher in rural areas than in urban areas between 2007 and 2015, this pattern largely reversed by 2017 (Hedegaard et al., 2020; Mack et al., 2017).

Because opioid overdose deaths can be prevented if naloxone is administered in time, naloxone has become the preferred treatment to reverse overdose effects and to reduce individual and community harm from opioid overdoses (Kim et al., 2009; McAuley et al., 2015). Although medical first responders and emergency departments have carried naloxone as standard practice for many years, response times may delay administration of naloxone to people who use drugs (PWUD) (Giglio et al., 2015). In addition, bystanders often are reluctant to call 911 in overdose situations due to fear of law enforcement involvement (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2015; Giglio et al., 2015). Many community-based organizations have implemented take-home naloxone (THN) programs to help ensure that PWUD, bystanders, and the general public have knowledge of the signs and symptoms of overdose and appropriate response strategies, including engaging emergency medical services, access to naloxone, and proper training to administer it in an overdose situation (McAuley et al., 2015; Wheeler et al., 2012; Wheeler et al., 2015). Although the design of THN programs varies widely across state and local jurisdictions, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, most THN programs included a face-to-face training component followed by distribution of THN (Bennett et al., 2011; Clark et al., 2014).

The Communities of Practice for Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (COP-RCORP) formed in 2018 with grant funding from the Health Resources and Service Administration's (HRSA) Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (RCORP). COP-RCORP includes leaders representing five community-based coalitions or opiate task forces located in Ohio's rural and/or Appalachian region; faculty and professional staff from Ohio University; and research scientists from the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (PIRE), a 501(c)3 research organization. COP-RCORP members, along with the participants from the local coalitions/task forces, function as a community of practice dedicated to addressing OUD and preventing opioid overdose deaths.

As part of the HRSA RCORP-Implementation (RCORP-I) grant, COP-RCORP is required to address 15 core activities within each of the RCORP-I grant's three focus areas—prevention, treatment, and recovery. For the past year, COP-RCORP has focused on developing, implementing, and assessing intervention models that leverage opioid overdose reversal and increased naloxone availability as a bridge to treatment to ensure that rural communities have sufficient access to naloxone (RCORP-I Prevention Core Activity #1). While the program made significant strides in this area prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, pivots in the design and implementation of THN programs by four of COP-RCORP's community-level coalitions/task forces maintained or enhanced THN access during the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 1 presents the average monthly distribution of THN kits for the year preceding the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2019–February 2020) and the average monthly distribution during the onset of the pandemic (March 2020–August 2020).

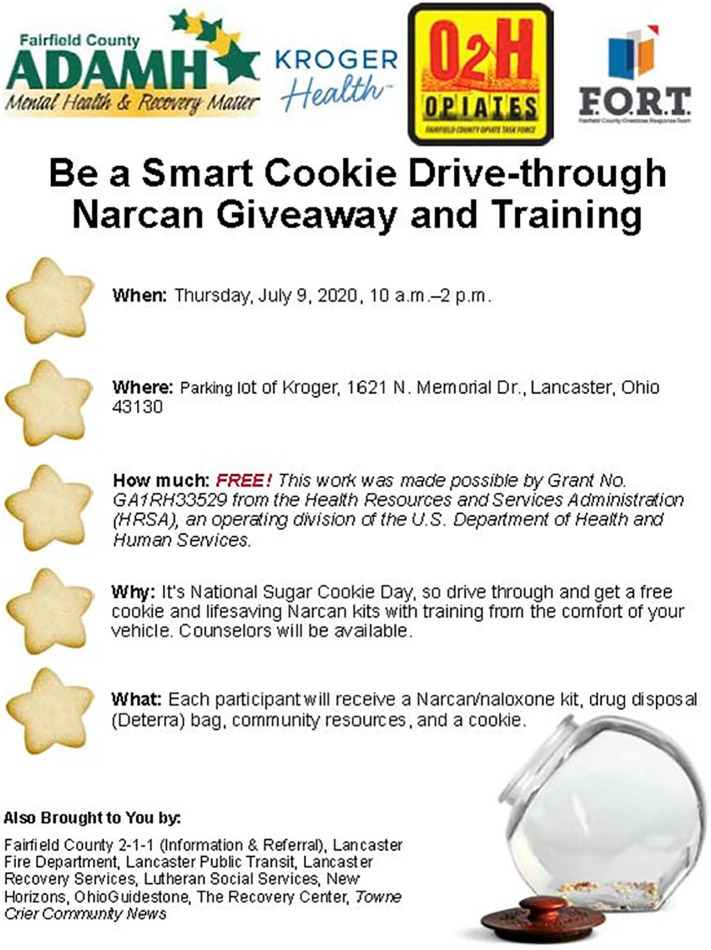

Fig. 1.

Sample advertisement for THN “Drive Thru” event.

Table 1.

Average monthly distribution of THN kits prior to and at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Community | Average monthly distribution: pre-pandemica | Average monthly distribution: onset of pandemicb |

|---|---|---|

| A | 16.58 | 22.67 |

| B | 7.83 | 21.33 |

| C | 0.00c | 0.67 |

| D | 9.58d | 35.00 |

March 2019 – February 2020.

March 2020 – August 2020.

This community was using the grant opportunity to begin a THN program just as the pandemic began.

THN kits were not available in this community until October 2019 when grant funding was received.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, each of the four community coalitions/task forces relied on in-person training and distribution of THN. Further, they recognized the importance of considering the needs of PWUD and their families as well as of providing an educational component prior to the distribution of THN. As the COVID-19 pandemic escalated, all four coalitions/task forces committed to continuing to provide THN training and distribution programming as a harm-reduction strategy. However, continuing THN training and distribution programs under the circumstances required innovative adaptations to each community's efforts. The innovative pivots to THN training and distribution that each of the communities made (see Table 2 ) reflect both the context of each community and the capacities of its service delivery and technology platforms.

Table 2.

Community pivots to THN programs at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Community | Historical THN Distribution | Adaptations to THN Distribution | Specific COVID-19 Precautions | Confidentiality Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Face-to-face training and distribution events such as conferences One-on-one training and distribution to individuals experiencing overdose and their families/significant others |

Hosting “Drive-Thru” Events promoted via social media, the organization's website, treatment providers, and community partners. An OCPSa provides one-on-one training at the event immediately prior to distribution. Providing one-on-one training from an OCPS over the phone or through videos posted on the agency website. THN kits are then distributed by a nurse via a drive thru station. Dispensing THN to clients engaged in MAT as they picked up prescriptions. Education was provided by an OCPS over the phone or though videos posted on the agency website. Promoting mail-order THN kits through Harm Reduction Ohiob. |

Masks, physical distancing, and regular hand and surface sanitizing when in-person contact is required. | OCPSs and nurses are trained in confidentiality procedures. |

| B | Face-to-face training and distribution events such as community town hall meetings One-on-one training and distribution to individuals experiencing overdose and their families/significant others |

Hosting “Drive-Thru” Events promoted via social media, l advertisements in local media,c treatment providers, and community partners. Trainers included volunteers with the following credentials: EMTs, firefighters, nurses, and a pharmacist. The trainer stood by the vehicle during the training. An informational handout was distributed with the kit. One kit was permitted per vehicle. Total interaction time was approximately 10–15 min. | Masks, physical distancing, regular hand and surface sanitizing when in-person contact is required, a nurse monitors temperatures of all volunteers at events. | Volunteers are trained in confidentiality procedures. |

| C | Did not have a THN program prior to the pandemic. Organization had just signed a contract with EMS to develop and provide face-to-face training and distribution events to the public at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic | Developing an online training platform placed on the organization's websited in SurveyMonkey because of the ability to embed videos and collect data. When training is complete, participants enter in personal information and check a box indicating that they completed the video training. The data is received by two health educators who mail the THN kit to the participants in a tamper proof white envelope. | None required | Health educators are trained in confidentiality procedures. In addition, the names and addresses of participants is kept in a binder stored in a locked cabinet. When THN kits are mailed, there are no identifiers on the package to indicate what the package contains. |

| D | Face-to-face training and distribution events such as community town hall meetings One-on-one training and distribution to individuals experiencing overdose and their families/significant others Group training and distribution at treatment sessions |

Providing one-on-one trainings by request via telephone or text to schedule a time. Promoting THN availability via social media, newspaper articles,e and the organization's website. Partnering with treatment agencies to provide small group trainings held in conjunction with regularly scheduled treatment groups (including groups comprised of clients engaged in MAT). |

Masks, physical distancing, regular hand and surface sanitizing when in-person contact is required, monitoring temperatures of all participants and staff at trainings Utilizing outdoor training spaces such as farmers markets Eliminating the interactive portion of training where attendees put each other into recovery position Eliminating the utilization of a demonstration THN kit to practice hand placement. |

Volunteers are trained in confidentiality procedures |

Ohio Certified Prevention Specialists.

See Fig. 1.

All four community pivots are both highly sustainable and transferrable to other community-based coalitions/task forces planning to or currently implementing THN training and distribution programs. Additionally, all four coalitions/task forces were able to increase their average monthly distribution of THN at a time when they were not providing traditional face-to-face training and distribution methods. Each of the coalitions/task forces found that their COVID-19 pivots complemented their existing THN efforts by increasing the number of options for training and distribution. Not only did the pivots increase the reach of these programs, they also increased the likelihood that THN will be available as needed for those most at risk for opioid overdose deaths. In addition, the expanded THN training and delivery methods likely will reduce community-level facilitators of stigma around THN because the adaptations de-emphasized in-person attendance at group meetings and provided flexibility for community members to connect to THN training and distribution in multiple ways. In the context of small, tight-knit rural communities, this flexibility is critically important to engaging community members in local THN programs. Finally, each of the coalitions/task forces found that although their pivots required creativity, they were able to seamlessly integrate these adaptations into their existing programs with comparatively few human and fiscal resources—this supports the notion that other community-based entities will be able to sustainably adapt as well.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Matthew W. Courser: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, revised draft. Holly Raffle: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing –original draft; writing and review—revised draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognize the participating project directors and members of the Communities of Practice for Rural Communities Opioid Response Program Master Consortium (Miriam Walton, Ashtabula County Mental Health and Recovery Services Board; Toni Ashton, Fairfield County Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Board; Stacey Gibson, Sandusky County Public Health; and Robin Reaves, Mental Health and Recovery Services Board of Seneca, Sandusky, and Wyandot Counties) along with the Ohio University/Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation Writing Circle. The authors also would like to thank the anonymous reviewers who provided helpful comments on an earlier version of this commentary. Their feedback—especially related to adding additional data and categorizing THN adaptations in a table format—made this work significantly stronger.

Funding

This work is supported by Grants G25RH32459, G25RH32461, GA1RH33529, GA1RH33532 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an operating division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Health Resources and Services Administration or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- Bennett A.S., Bell A., Tomedi L., Hulsey E.G., Kral A.H. Characteristics of an overdose prevention, response, and naloxone distribution program in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(6):1020–1030. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9600-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney-Koen D. Issue brief: Reports of increases in opioid-related overdose and other concerns during COVID pandemic (AMA issue brief 9-2020) 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-09/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf Retrieved from.

- Clark A.K., Wilder C.M., Winstanley E.L. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2014;8(3):153–163. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction . Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2015. Preventing fatal overdoses: a systematic review of the effectiveness of take-home naloxone.https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/932/TDAU14009ENN.web_.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Giglio R.E., Li G., DiMaggio C.J. Effectiveness of bystander naloxone administration and overdose education programs: a meta-analysis. Injury Epidemiology. 2015;2(10) doi: 10.1186/s40621-015-0041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H., Miniño A.M., Warner M. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2020. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018 (National Center for Heath Statistics Data Brief, No. 356) [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Irwin K., Khoshnood K. Expanded access to naloxone: options for critical response to the epidemic of opioid overdose mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(3):402–407. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack K.A., Jones C.M., Ballesteros M.F. Illicit drug use, illicit drug use disorders, and drug overdose deaths in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas — United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2017;66:1–12. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6619a1. (No. SS-19) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley A., Aucott L., Matheson C. Exploring the life-saving potential of naloxone: A systematic review and descriptive meta-analysis of take home naloxone (THN) programmes for opioid users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2015;26(12):1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickler G.K., Kreiner P.W., Halpin J.F., Doyle E., Paulozzi L.J. Opioid prescribing behaviors — Prescription behavior surveillance system, 11 States, 2010–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2020;69:1–14. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6901a1. (No. SS-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler E., Davidson P.J., Jones T.S., Irwin K.S. Community-based overdose prevention programs providing naloxone—United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61(6):101–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler E., Jones T.S., Gilbert M.K., Davidson P.J. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons - United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2015;64(23):631–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]