Abstract

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft tissue sarcoma in children. Although significant efforts enabled the identification of common mutations associated with RMS, and allowed discrimination of different RMS subtypes, major challenges still exist for the development of novel treatments to further improve patients’ prognosis. Although identified by the expression of myogenic markers, there is still significant controversy on whether RMS has myogenic or non-myogenic origin, as the cell of origin is still poorly understood. In the present study, we provide a reliable method for the tumorsphere assay for mouse RMS. The assay is based on functional properties of tumor cells and allows the identification of rare populations within the tumor with tumorigenic function. We also describe procedures for testing recombinant proteins and integrating transfection protocols with the tumorsphere assay, for evaluating candidate genes involved in tumor development and growth. We further describe a procedure for allograft transplantation of tumorspheres into recipient mice, to validate tumorigenic function in vivo. Overall, the described method allows reliable identification and testing of rare RMS tumorigenic populations that can be applied to RMS arising in different contexts. Finally, the protocol can be utilized as a platform for drug screening and future development of therapeutics.

Keywords: Tumorspheres, Rhabdomyosarcoma, skeletal muscle, primary cells, recombinant protein treatment, plasmid transfection

SUMMARY:

This protocol describes a reproducible method for isolation of mouse rhabdomyosarcoma primary cells, tumorspheres’ formation and treatment, and allograft transplantation starting from tumorspheres cultures.

INTRODUCTION:

Cancer is a heterogeneous disease: the same type of tumor can present different genetic mutations in different patients, and within a patient a tumor is composed by multiple populations of cells1. Heterogeneity presents a challenge in the identification of the cells responsible for initiating and propagating cancer, but their characterization is essential for the development of efficient treatments. The notion of tumor propagating cells (TPC), a rare population of cells that contribute to tumor development, has been previously extensively reviewed2. Despite TPCs have been characterized in multiple types of cancer, the identification of markers for their reliable isolation remains a challenge for several tumor types3–9. Thus, a method that does not rely on molecular markers, but rather on TPC functional properties (high self-renewal and ability to grow in low-attachment conditions), tumorspheres’ formation assay, could be widely applied for the identification of TPCs from most tumors. Importantly, this assay can also be employed for expansion of TPCs and thus directly applied for cancer drug screening and studies on cancer resistance1,10.

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare form of soft tissue sarcoma most common in young children11. Despite RMS can be histologically identified through assessment of expression of myogenic markers, RMS cell of origin has not been univocally characterized due to the multiple tumor subtypes and the high heterogeneity of the tumor developmental stimuli. Indeed, recent studies generated significant scientific discussion in the field on whether RMS are of myogenic or non-myogenic origin, suggesting that RMS may derive from different cells types depending on the context12–17. Numerous studies on RMS cell lines were performed employing the tumorspheres’ formation assay for the identification of pathways involved in tumor development and characterization of markers associated highly self-renewal populations18–21. However, despite the potential that tumorspheres’ formation assay has for identifying RMS cells of origin, a reliable method that can be employed on primary RMS cells, has not been described yet. In this context, a recent study from our group employed an optimized tumorspheres’ formation assay for the identification of the RMS cells of origin in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy mouse model22. Multiple pre-tumorigenic cell types, isolated from muscle tissues, were tested for their ability to grow in low attachment conditions, allowing the identification of muscle stem cells as cells of origin for RMS in dystrophic contexts. Here we describe a reproducible and reliable method for the tumorsphere formation assay protocol (Figure 1), which has been successfully employed for the identification of extremely rare cell populations, responsible for mouse RMS development.

Figure 1: Tumor cells isolation, tumorspheres derivation and transplantation.

(A) Schematic representation of Protocol 1 for tumor cells isolation. Each key step of the protocol is summarized. (B) Schematic representation of Protocol 2 for tumorspheres derivation. Each key step of the protocol is summarized. (C) From left, bright field image of isolated tumor cells at passage 2 (P2) at low magnification (scale bar: 50 μm), and high magnification (scale bar: 50 μm), bright field image of a tumorsphere derived from tumor cells after 30 days in suspension culture (scale bar: 250 μm), and bright field image of a cell cluster formed from tumor cells after 30 days in suspension culture (scale bar: 50 μm). (D) Schematic representation of Protocol 5 for tumorspheres allograft transplantation. Each key step of the protocol is summarized.

PROTOCOL:

The housing, treatment, and sacrifice of mice were performed following the approved IACUC protocol of the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute.

1. Reagents Preparation

-

1.1)

Prepare 100 mL of cell isolation media: F10 medium supplemented with 10% horse serum (HS).

-

1.2)

Prepare 50 ml of collagenase type II solution: dissolve 1 g of collagenase type II powder in 50 mL of cell isolation media (note down units of the enzyme per ml of media, since number of units change depending on the lot). Aliquot the solution and store in the −20°C freezer until ready to use.

NOTE: Every lot of collagenase should be tested before use, since the enzyme activity might change across different lots.

-

1.3)

Prepare 10 ml per sample of second digestion solution: cells isolation media with 100 units/mL of collagenase type II solution and 2 units/ml of dispase II freshly weighted. To be prepared immediately before use.

-

1.4)

Prepare 500 mL of tumor cells media: DMEM high glucose supplemented with 20% FBS, and 1% Pen/Strep.

-

1.5)

Prepare 500 mL of FACS buffer: 1X PBS supplemented with 2.5% v/v normal goat serum and 1mM EDTA.

-

1.6)

Prepare 500 mL of tumorspheres’ media: DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1% Pen/Strep. Just before use, add the following growth factors: 1% N2 supplement, 10 ng/mL EGF, and 10 ng/mL β-FGF.

2. Protocol 1: Cells isolation and culture

-

2.1)

Prepare a 10-cm plate containing 5 ml of cells isolation media (one plate per tumor sample) and place it in the incubator at 37°C until ready to harvest the tumor tissue.

-

2.2)

RMS have been reported to spontaneously develop in both male and female mouse models for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, such as B10 mdx mice at around 18 months of age and in B6 mdx/mTR mice by 9 months22,23. Anesthetize the mouse that developed the RMS tumor using isoflurane and sacrifice the animal through cervical dislocation, or according to the IACUC guidelines of your institution. With scissors, make an incision on the skin, in the area where the tumor is localized, and, using tweezers, pull the skin away from the area of interest. Employing a razor blade excise the tumor from the animal.

-

2.3)

Weight out 500 to 1000 mg of the tumor tissue and place it in the plate prepared in step 2.1 (Figure 1A).

NOTE: Larger amounts of tissue negatively affect the digestion steps, and decrease the overall yield. If the harvested tumor is larger than 1000 mg, divide it into parts and sample them randomly until the desired weight is reached. Random sampling is necessary for evaluating tissue heterogeneity.

-

2.4)

Place the plate containing tumor tissues in the sterile cell culture hood and mince it employing a razor blade. Tumor tissue from RMS is heterogeneous, thus different areas might present different resistance to the cut. Make sure that the size of the resulting minced pieces is uniform, to ensure optimal digestion.

NOTE: RMS exists as mixtures of different tissue types, mainly fibrotic, vascularized, and fatty tissues can be identified in every tumor. In order to isolate a heterogeneous cell population accurately recapitulating the composition of the original tumor and to not bias the isolation procedure, perform random sampling of the harvested tissue. Cells from different areas of the tumor should be digested and tested in parallel in vitro in the assay described in Protocol 2.

-

2.5)

Move the minced tissue and cell isolation media in a 15 mL centrifuge tube, wash the plate with 4 mL of cell isolation media, and place it in the tube.

-

2.6)

Add 700 units/mL of collagenase solution to digest the tissue and incubate in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 1.5 hours.

-

2.7)

After incubation, spin down the tissue at 300 g for 5 minutes at RT. Aspirate the supernatant without disturbing the pellet, resuspend the pellet in 10 mL of second digestion solution (dispase), and incubate in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 30 minutes.

-

2.8)

Once the second digestion is completed, pipet up and down and pass the cell suspension through a 70 μm nylon filter on a 50 mL centrifuge tube, then add 10 mL of cell isolation media to wash the filter and dilute the digestion solution, and spin down the tissue at 300 g for 5 minutes at RT.

-

2.9)

Aspirate the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in 20 mL of tumor cells media, then transfer the cell suspension in a 15-cm cell culture plate. Place the cells in the incubator at 37°C overnight. This plate is going to be identified as P0.

-

2.10)

The day after isolation change the media. This step is necessary for ensuring removal of debris and dead cells that might negatively influence cell survival. Cell confluency can be assessed after media is changed, and it ranges from 30% to 60% depending on the amount of starting material, and cell size. Leave the cells growing in the incubator until they reach 90% confluency. Cells need to be monitored every day and media need to be changed every 2 days. The time necessary for tumor cells to become confluent varies depending on multiple parameters: tumor aggressiveness, genotype of the tumor, age of the mouse, heterogeneity of the tissue.

-

2.11)

Cell passaging

-

2.11.1)

Pre-warm the cell detachment solution and tumor cells media in a water bath at 37°C.

-

2.11.2)

Wash the cells with 1X sterile PBS and incubate them at 37°C in 10 mL of warm cell detachment solution for 5 to 10 minutes.

-

2.11.3)

When all the cells are detached from the plate, add 10 ml of warm tumor cells media, move the solution into a 50 mL centrifuge tube and spin cells down at 300 g for 5 minutes at RT.

-

2.11.4)

Resuspend the cells in 5 to 10 mL of tumor cells media, depending on the pellet size, and count live cells using Trypan blue (1:5 dilution), to exclude dead cells.

-

2.11.5)

Plate 105 cells in 10 cm plates, or 3 × 105 cells in 15 cm plates. Cells doubling time varies depending on factors detailed in section 2.10.

2. Protocol 2: tumorspheres derivation

-

3.1)

Use tumor cells at passage P1 or P2 in order to avoid cell selection through multiple passages (Figure 1B). To detach cells from the plate, first wash the dish with 1X PBS, without disturbing the cells, then cover them using cell detachment solution (5 ml for 10-cm plate or 15 ml for 15-cm plate) and place them in the incubator for 5–10 minutes.

-

3.2)

Confirm cells are detached by looking at the plate under a bright field microscope, add 1:1 volume of tumor cells media (cell detachment solution: tumor cells media), place the cell suspension in a centrifuge tube and spin the cells down at 300 g for 5 minutes at RT.

-

3.3)

Resuspend cells in either FACS buffer (sections 3.4) or in tumorspheres media (section 3.5), according to the method used for plating.

-

3.4)

Plating cells through flow cytometer

-

3.4.1) Resuspend cells in FACS buffer (the amount depends on the pellet size) and manually count live cells using trypan blue exclusion. Make sure that the final cell concentration is 107 cells/mL (100 μL of FACS buffer per 106 cells). Add 1 μl of Fx Cycle Violet stain every 106 to discriminate live from dead cells during the cell sorting. Prepare an unstained control where Fx Cycle Violet stain is not added to the cells.

NOTE: The concentration is optimized for efficient staining and speed during sorting. Lower cell concentration will result in longer sorting time, while higher concentration will affect staining.

-

3.4.2) Employing the unstained control, set up a FACS gate segregating alive (Fx Cycle Violet-) from dead (Fx Cycle Violet+) cells. Fluorescent activated cell sorting (with 450/50 filter band pass) will be then employed for separation and count of live/dead cells and for plating the desired number of live cells in each well of the 96 well low-attachment plates. Each well of the plate needs to be filled with 200 μL of tumorspheres media before starting the sort.

NOTE: Given that TPCs are a rare subpopulation within the whole tumor, we optimized the protocol by plating 100 cells/well from mouse RMS, in order to be able to observe the formation of tumorspheres in suspension culture. Cell number per well should be adjusted for the specific tumor tested.

3.4.3) Place cells in the incubator until the end of the experiment. Try not to disturb the plate unless necessary. For a 30-day long experiment, each well should be replenished with media and appropriate proportion of growth factors every week (media tend to evaporate and growth factors are not effective after a week).

-

3.4.4.) After completion of the experiment, manually screen plates under a bright field microscope to identify tumorspheres. See section 3.6.

NOTE: The time point of 30 days was optimized to easily detect mouse RMS tumorspheres of a size ranging from 50 to 300 μm of diameter. The time point should be adjusted depending on the aggressiveness of the tumor tested and its proliferative rate.

-

3.5)

Plating cells manually

-

3.5.1)

Resuspend cells in tumorspheres’ media (the amount depends on the pellet) and manually count live cells using trypan blue (1:10 dilution). Calculate the cell concentration in the tube and plate the proper number of cells in a 96-well low attachment plate. Cells will be placed in the incubator until the end of the experiment. Try not to disturb the plate unless necessary for replenishing media and growth factors, as described in 3.4.3.

-

3.5.2)

After completion of the experiment, screen plates manually under a bright field microscope to identify tumorspheres or using the Celigo software, as previously described in Kessel et al.24. See section 3.6.

-

3.6)

Two separate readouts can be evaluated as result of this assay: number and size of formed tumorspheres.

NOTE: When more than one cell is plated in a well, either tumorspheres or cell clusters can form (Figure 1C, third and fourth panels). Cell clusters are small cellular aggregates that form in suspension culture that enhance cell survival and are characterized by an irregular shape. Tumorspheres are large and have a more compact structure with a spheroid shape. They derive from a single cell that has the ability to survive in an anchorage-independent manner and proliferate at a high rate25.

NOTE: Plating cells through flow cytometer or manually can be used interchangeably, depending on the capabilities available in the laboratory. Moreover, employing low-attachment plates of sized different than 96-well plates is possible, and dependent on the required outcome. Indeed, assessment of tumorspheres frequency should be done employing 96-well low attachment plates, whereas initial screening for assessment of cells tumorigenic potential will yield faster and still reliable results on 6-well low attachment plates.

4. Protocol 3: tumorspheres’ treatment with recombinant proteins

- 4.1)

-

4.2)

If setting up a treatment with recombinant proteins, first determine the best concentration to use follow section 4.3, or, if the optimal concentration has been previously determined, follow section 4.4.

-

4.3)

Determination of recombinant protein treatment concentration

-

4.3.1)

Resuspend the cells in tumorspheres’ media (the volume depends on pellet size) and manually count live cells using trypan blue exclusion. Calculate cell concentration in the tube and plate 100,000 cells in a 6-well low attachment plate. Plate 2 wells per each concentration tested and 2 wells for untreated control (Figure 2). Protein concentrations to be tested are based on literature search.

-

4.3.2)

Treat each well of suspension cells with a different protein concentration and place the cells in the incubator for 48 hours (time necessary to be able to evaluate the effect of the treatment on both cell viability and on the expression of downstream target genes). Then assess the following parameters:

-

-

Cell survival: using a bright field microscope, as well as comparison with untreated controls, check cell morphology. Healthy cells look bright and reflective under the microscope, while excessive cell death will induce the accumulation of debris in the media. For a quantifiable determination of cell death, trypan blue exclusion, crystal violet staining, MTT, or TUNEL assay could be employed (in this case add one well to the original plating).

-

-

Effect of recombinant proteins on downstream pathways: perform a literature search using PubMed, for identification of the downstream genes known to be affected by the tested protein. Design qRT-PCR primers for the target genes, and perform qRT-PCR analysis on the RNA isolated from the treated cells (Figure 2).

-

-

-

4.4)

Recombinant protein treatment

-

4.4.1)

Resuspend the cells in tumorspheres’ media (the volume depends on pellet size) and manually count live cells using trypan blue exclusion. Determine the total number of cells needed for the desired experiment (100 cells per each well of a 96-well low attachment plate) and dilute them in the appropriate tumorspheres’ media volume. If performing more than one treatment, prepare separate cells’ tubes.

-

4.4.2)

Treat each tube with the appropriate concentration of recombinant protein and plate the cells in a separate well of 96-well low-attachment plate. The treatment will be repeated on each well depending on the half-life of the recombinant protein until the 30-day endpoint of the experiment.

-

4.4.3)

At the end of the experiment, follow section 3.4.4 and 3.6 from protocol 2 to analyze the data.

Figure 2: Validation of downstream target genes for determination of recombinant protein concentration.

qRT-PCR results for assessment of Flt3l treatment concentration. Two-way ANOVA was performed, significance shown for the comparison with non-treated control. (*: p-value<0.05; **: p-value<0.01; ***: p-value<0.001; n=3).

5. Protocol 4: tumorspheres’ treatment with overexpression plasmids

- 5.1)

-

5.2)

If setting up the treatment on a new tumor type, first determine the best concentration of plasmid to use following section 5.3, or, if the optimal DNA concentration has been previously determined, follow section 5.4.

-

5.3)

Determination optimal plasmid concentration

-

5.3.1)

Resuspend cells in tumor cells media (the volume depends on pellet size) and manually count live cells using trypan blue exclusion. Plate the counted cells to achieve a confluency from 70% to 90% (cell number is highly dependent in cell size and morphology). GFP-plasmid will be employed to test transfection efficiency following the manufacturer protocol of the transfection reagent for adherent cells. In parallel, also test an untreated control (Figure 3A). Perform efficiency test in a 24-well plate.

NOTE: Adherent cells are used to enhance the transfection efficiency, as transfection performed on suspension cells is not efficient and negatively affects cell viability.

-

5.3.2)

48 hours after transfection assess cells for the following parameters:

-

-

Cell survival: using a bright field microscope, compare the number of cells present in each-well and compare it to the untreated cells well.

-

-

GFP expression: count the percentage of cells that are GFP positive over the total number of cells in each well (Figure 3B).

-

-

-

5.4)

Overexpression plasmid treatment

-

5.4.1)

Resuspend cells in tumor cells’ media (the volume depends on pellet size) and manually count live cells using trypan blue exclusion. Plate 200,000 cells per well of a 6-well plate. Each well will be used for an independent transfection event. Each well will be transfected, using the protocol set up developed for the specific tumor type (Figure 3A).

-

5.4.2)

24 hours after transfection, wash each well with 1X PBS and incubate cells in warm cell detachment solution (should be enough to cover the well). Place the plate in the incubator at 37°C for 5–10 minutes, depending on factors detailed in section 2.15.

-

5.4.3)

When cells are detached, count the cells derived from each single well independently using trypan blue exclusion. Place 100,000 cells per well of a 6-well low attachment plate, making sure not to mix cells derived from different wells. Place the plate in the incubator at 37°C and leave undisturbed for a week.

NOTE: The duration of this assay is 7 days, a sufficient time to allow tumorspheres’ formation while preventing tumorspheres fusion. Tumorspheres’ fusion is a phenomenon that becomes evident when 100,000 or more cells are plated together in suspension for over a week, and can bias the assessment of tumorsphere formation ability. In the event the experiment requires longer incubation time, cell density can be adjusted or polymeric scaffolds can be used to avoid tumorspheres fusion26.

-

5.4.4)

At the end of the experiment, follow section 3.5.2 and 3.6 from protocol 2 to analyze the data.

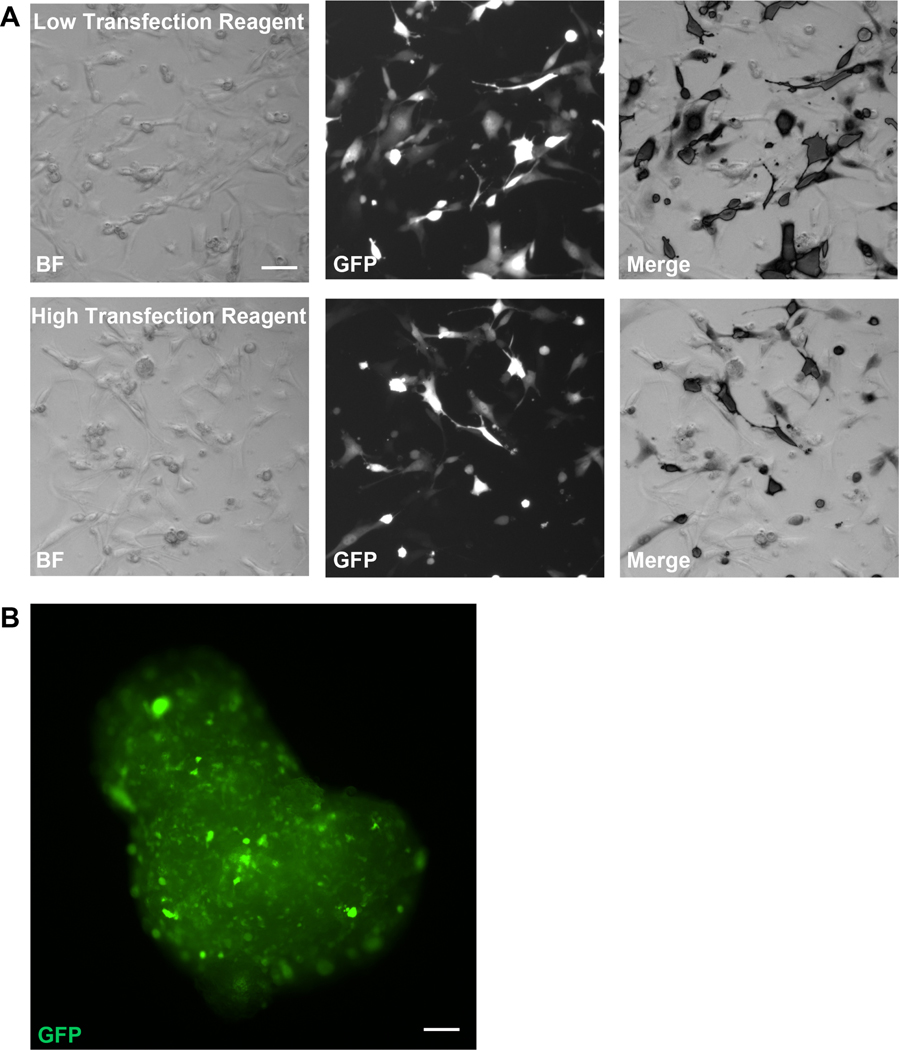

Figure 3: Set up of tumorspheres transfection protocol.

(A) Representative bright field and fluorescent images of tumor cells treated with low (top) or high (bottom) concentration of transfection reagent (0.75 μL or 1.5 μL in 24 well plates) (scale bar: 50 μm). (B) Representative image of tumorspheres formed from GFP plasmid-treated cells, 7 days after plating the cells in suspension (scale bar: 50 μm).

6. Protocol 5: tumorspheres’ preparation for allograft transplantation

-

6.1)

Place extracellular matrix (ECM) solution (50 μL per allograft) and tumor cells media (50 μL per allograft) on ice.

-

6.2)

Tumorspheres can be used for allograft transplantations. Pull together all the tumorspheres obtained from a specific cell type or treatment into a 15 mL or 50 mL tube (according to the total volume of media) (Figure 1D). Spin the tumorspheres down at 300 g for 5 minutes at RT. Remove the supernatant over the tumorspheres and wash them with 10 mL of sterile 1X PBS.

-

6.3)

Spin the tumorspheres down again at 300 g for 5 minutes at RT, aspirate the 1X PBS and add 500 μL to 1 mL of cell detachment solution on top of the cell pellet, to start the dissociation process. Incubate tumorspheres in digestive solution into a shaking water bath at 37 °C and check the progression of the digestion every 10 minutes. To help tumorspheres dissociation into a single cell solution, pipette the cells up and down for mechanical disruption. The digestion process might take up to 30 minutes.

NOTE: Despite incubation time varies considerably when tumorspheres are derived from different primary RMS cells, significant decrease in cell viability in relationship to digestion time was never observed.

-

6.4)

When a single cell solution is obtained, add a volume of tumor cells media (1:1, cell detachment solution: tumor cells media) and spin it down at 300 g for 5 minutes at 4 °C.

From this time on all the steps need to be performed on ice.

NOTE: After spinning, tumorspheres do not form a stable pellet, as single cells solutions do. To make sure not to dislodge or aspirate the tumorspheres use a 1 mL pipette and gently aspirate the liquid. Move to a 200 μL pipette when only 1 mL is left.

-

6.5)

Resuspend cells in cold tumor cells media (the volume will depend on pellet size), place the cells on ice and count live cells using trypan blue exclusion. After determining the proper amount of cells to use for the allograft, resuspend them in a total volume of 50 μL of cold tumor cells media. Cool down a pipette tip in cold tumor cells media. When the tip is cold, use it to take 50 μL of ECM solution and add it into the tube containing cells. Do not remove the tubes from the ice during the process.

NOTE: The number of cells to use for the transplant should be determined according to the tumor tested and the experimental goal: a larger number of transplanted cells will decrease the time of tumor development (20,000 cells from mouse RMS tumorspheres developed into a tumor 6 weeks after injection). In order to be able to compare different cell lines or different treatments, it is important to start from the same number of cells.

-

6.6)

Cells are now ready for transplantation, and will be maintained on ice until injection. Place a capped 0.5 ml insulin syringe with a 29G needle on ice, to prevent the cell solution to become solid upon aspiration.

-

6.7)

Turn on the flowmeter to 200 ml/min oxygen and the isoflurane vaporizer to 2.5 %. Anesthetize a 2 month old male NOD/SCID mouse placing it inside the induction chamber. Wait 2–3 min until the mouse appears asleep and the breeding has slowed down. Before starting the procedure first confirm, through foot pinch, that the mouse is asleep, and then apply vet ointment on the eyes. Shave the right side of the animal, aspirate the cell solution in the pre-cooled syringe and inject them subcutaneously into the shaved area. A visible bump under the skin will form if the injection is performed correctly.

NOTE: Cells allograft can be performed in the same mouse strain as that of the transplanted cells: for example, if the RMS cells were originally isolated from a C57BL/6 mouse, the allograft can be performed into C57BL/6 mice. If the strain is different, then immunodeficient recipient mice should be utilized, to avoid rejection. Age of recipient mice can also be adjusted depending on the experimental goal.

-

6.8)

Monitor the mice for tumor formation once per week.

NOTE: To validate identity of the tumor derived from allograft transplantation, it should be compared to the original tumor from which the cells were isolated. To this aim, histological analysis for morphological features, expression of myogenic markers and more comprehensive RNAseq can be performed.

REPRESENTATIVE RESULTS:

Tumorspheres detection

Cell isolation was optimized to obtain the maximum heterogeneity of cell populations present in the tumor tissue. First, since isolated tissues presented morphologically dissimilar areas, to enhance the chances to isolate even rare cell populations, sampling was performed from multiple areas of the tumor (Figure 1A, first panel on the left). Second, mechanical dissociation of the harvested samples was performed maintaining homogeneity in the minced tissue size, despite different resistance might present across the samples (Figure 1A, third and fourth panel from the left). Depending on the starting material (tumor aggressiveness, age and genotype of mouse, tumor location), recovery of the cells from the mechanical stress of the isolation process may vary, ranging from 3 to 7 days (Figure 1A, last panel on the right). To enhance cell survival and growth, media should be changed the day after isolation and then every 2 days. This will remove the debris and dead cells accumulated during the isolation process that might affect to cell viability. Tumorspheres’ formation assay should start after the cells have been passaged at least once, in order to ensure optimal viability when placed in suspension cultures (Figure 1B, first panel on the left). In our hands, optimal results were obtained starting with cells from passage 2 (P2) (Figure 1C, first and second panel on the left). This specific passage was chosen after multiple testing. When P0 cells were plated in low-attachment conditions they would form a low number of tumorspheres, compared to later passages, possibly due to cellular debris that are still present after isolation. In later passages different patterns of tumorsphere formation were observed and could be attributed to the selection that occurs after numerous passages in culture. When different cell lines are compared, it is suggested to start from the same passage.

Discrimination between tumorspheres and cell clusters is of fundamental importance for quantification of the assay. Figure 1C (last two panels on the right) clearly shows the morphological differences between a tumorsphere (left) and a cell cluster (right). Tumorspheres derive from a single cell that has high ability to self-renew and grow in low attachment conditions, features of TPCs. Indeed, tumorspheres development indicates tumorigenicity potential. However, this assay is performed in vitro independently from the cues derived from the whole organism. Thus, to validate cells’ tumorigenic potential in vivo, allografts transplantation experiments should be performed (Figure 1D).

Validation of recombinant proteins treatment

Before setting up tumorspheres treatment, the optimal concentration at which the protein of interest triggers an effect on tumor cells should be determined. To do so, assessment of the level of expression of the protein’s downstream target genes is necessary (Figure 2A). Literature search on PubMed was performed before determining the target genes to test through qRT-PCR. In the event the protein of interest has been shown to modulate different downstream pathways, selection of multiple genes associated with each of these pathways should be performed. For instance, Flt3l (Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3) has been shown to modulate STAT5 signaling in acute myeloid leukemia, inducing the downstream expression of p21, c-Myc, and CyclinD1 (Figure 2)27. Moreover, expression of Flt3l is required for dendritic cells differentiation mediating activation of STAT3 signaling pathway28. To assess STAT3 activity Socs3 and CyclinD1 expression were checked (Figure 2). Analysis of the results showed a dose dependent effect of recombinant protein treatment on some of the tested genes (p21, CyclinD1, and Socs3), whereas others were not affected (c-Myc). It is important to determine the downstream genes responsive to the protein of interest in the specific tumor tested, for reliable assessment of treatment effectiveness.

Optimization of the protocol for plasmid transfection

To establish an efficient protocol for plasmid transfection and further tumorspheres’ formation assay, the effect of transfection on adherent tumor cells was first tested (Figure 3A). Transfection reagent treatment was performed, following the manufacturer protocol, and 2 different amount of the reagent were tested. Efficiency was assessed employing a GFP reporter plasmid. In our hands, we observed a higher transfection efficiency using lower amounts of the reagent (Figure 3A). Indeed higher concentrations lead to increased cell death, starting at 48 hours and becoming more evident after 72 hours from the time of transfection. The same transfection protocol was not efficient on cells in suspension, as accumulation of dead cells and cellular debris became evident 24 hours after the beginning of the treatment, indicating decreased cellular viability. To overcome this technical challenge, a two steps protocol was employed: perform transfection on adherent cells, detach them 24 hours after the treatment, and plate them in suspension for 7 more days. Control tumorspheres were indeed expressing GFP at the end of the experiment (Figure 3B).

DISCUSSION:

Multiple methods have been employed for isolation and characterization of TPCs from tumor heterogeneous cell populations: tumor clonogenic assays, FACS isolation, and tumorspheres’ formation assay. The tumor clonogenic assay was first described in 1971 and used for stem cells studies and only subsequently applied to cancer biology29,30. This method is based on the cancer stem cells intrinsic property to expand without constraints in soft gels cultures31. Since its development, this method has been widely used in cancer research for multiple purposes, including tumor cell heterogeneity studies, effect of hormonal treatment on cell growth, and tumor resistance studies31. To date, this assay is still employed for the identification of tumor initiating cells for multiple types of cancers32.

FACS isolation is based on prior knowledge of molecular markers present on the surface of cells on interest. It has been widely utilized for the isolation of TPCs from both liquid and solid tumors. For example, the first identification of human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) initiating cells by Dr. Dick’s group, was performed by utilizing FACS fractionation and transplantation assays based on the knowledge of the markers present on bulk AML cells9. Utilizing a similar approach, Dr. Clarke’s group isolated breast cancer initiating cells3. Tumorspheres’ formation assay is a different approach used for the identification and study of TPCs. This method was first developed to identify cancer stem cells from brain tumors33. Interestingly, it was initially tested using the same conditions known to favor neural stem cells growth, thus favoring the self-renewal property also associated with TPCs33. Moreover, tumorspheres’ formation relies on the capacity of TPCs to growth in an anchorage-independent manner. The three above described approaches can be used in parallel to enhance the probability to isolate and molecularly characterize TPCs populations, overcoming the limitations of each method. For instance, FACS, despite bringing the great advantage of isolating pure cell populations, strongly relies on the use of surface markers that are not yet known for all cancer types. Thus, its use is limited to the isolation of TPCs expressing known markers. Tumor clonogenic and tumorspheres’ formation assays are both based on cellular properties, known to be associated with TPCs. Both these methods can be employed as the first line of studies on new or not yet studied cancers. Moreover, these two methods can ensure the expansion and enrichment of the cell population of interest, facilitating the identification of molecular markers, and allowing for both cancer resistance and drug screening studies. In this context, tumorspheres’ formation assay is more advantageous, since these spheroid structures better recreate the environment present in tumor tissues (hypoxic areas in the center of the spheres)34. Indeed, it has been previously shown that 3D cultures are more reliable for predicting drug treatments outcome34. Tumorspheres can be recovered after culture, and used for allograft experiments: digestion of tumorspheres into single cells solutions and transplantation into recipient mice will allow for in vivo assessment of tumorigenic capacity of newly identified TPCs, compared to bulk tumor cells.

To successfully obtain a starting cellular material representative of tumor heterogeneity, it is critical to first perform random sampling of the tissue. RMS are characterized by fibrotic, fatty, or highly vascularized areas which are clearly distinguishable in isolated tumors, thus, to maintain this cellular diversity, collection of each area of the tissue will be required. Moreover, to enhance the chances of cells survival during the digestion process, mincing of the collected tissue needs to result in evenly sized pieces: smaller fragments are more likely to be overdigested inducing reduction of cells viability. This might be particularly tedious due to the diverse morphology and stiffness of RMS.

For quantification of the result of tumorspheres’ formation assay, it is of critical importance to distinguish between real tumorspheres and cellular clusters (Figure 1C, last two panels on the right). A tumorsphere is solid spheroid structure, in which it is not possible to discriminate the cells that compose it, whereas in a cell cluster single cells can be easily discriminated. Cell cluster might not assume a rounded shape and are significantly smaller where compared to tumorspheres, which range between 50 μm to 250 μm25.

To achieve tumorspheres transplantation, obtaining a uniform single cells solution is a key step. Indeed, given the tight structure and large size of a tumorsphere, digestion of the cells becomes a major limiting step in the preparation of a single cell suspension, that will be further employed for transplantation. Multiple cycles of enzymatic digestion combined to mechanical dissociation will be necessary for complete dissociation of tumorspheres. To confirm the progress of dissociation and successful outcome, the solution will need to be monitored under a bright field microscope.

Despite the multiple advantages provided by the tumorspheres’ formation assay, tumorspheres have been shown not to originate from every type of tumor or from all commercially available cell lines. In these cases, the assay cannot be employed as standard for determination of cells tumorigenicity and for quantification of TPCs within an heterogeneous population. Another limitation associated with this assay is associated with the fact that different tumor types require different growing and dissociation conditions, thus requiring time consuming optimization and troubleshooting of both protocols for each tumor type or cell line that needs to be investigated. Moreover, fusion of multiple tumorspheres might occur in culture, making assessment of the tumorspheres’ size and number complicated and not clear.

Despite tumorspheres’ formation assay has been previously utilized in RMS studies, the assay has been mainly applied to commercially available RMS cell lines in order to identify the molecular pathways involved in tumor formation and development18,20,21. Given the heterogeneous tissue composition, the numerous subtypes of tumors, and the diverse developmental contexts from which RMS can originate, employment of RMS cell lines limits the application of tumorspheres’ formation assay for the identification of both cell of origin and developmental cues leading to tumor development in vivo. An attempt to develop an efficient protocol for tumorspheres derivation, starting from human sarcoma samples, showed poor results: indeed tumorspheres could be developed only from 10% of the samples35. Thus, there is a need for a reproducible and reliable assay for isolation of primary RMS cells and tumorspheres development. In response to this need, we optimized a tumorspheres’ formation assay that can be employed on primary cell cultures. The development of this protocol is the first step towards answering the major questions in the field: are RMS cells of origin different depending on the environmental context? In more detail, here we describe a reproducible protocol for isolation of primary tumor cells from RMS tissues, for formation of tumorspheres and tumorsphere treatment (both performed with recombinant proteins or overexpression plasmids), and for allograft transplantations experiments.

In conclusion, the tumorspheres’ formation assay is a well-established and versatile method for identification of TPCs in different types of tumors, enriching for those cells with increased self-renewal capacity and ability to grow in anchorage-independent manner. This assay is based on functional characteristics of the cell populations to be studied, not on the previous knowledge of molecular markers, thus it can be applied as an exploratory tool for a wide range of tumors types. Moreover, the isolation of rare cell populations achieved through tumorspheres’ culture, make this in vitro assay an ideal platform for cancer drug testing.

Boscolo et al. Table of Materials

| Name of Material/Equipment | Company | Catalog Number | Comments/Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMEM/F12 Media | Gibco | 11320033 | Component of tumosphere media |

| DMEM high glucose media | Gibco | 11965092 | Component of tumor cells media |

| Ham’s F10 Media | Life Technologies | 11550043 | Component of FACS buffer |

| Penicillin - Streptomyocin | Life Technologies | 15140163 | Component of tumosphere and tumor cells media |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Omega Scientific | FB-11 | Component of tumor cells media |

| Goat Serum | Life Technologies | 16210072 | Component of FACS buffer |

| Recombinant Human βFGF-basic | Peprotech | 10018B | Component of tumosphere media |

| EGF recombinant mouse protein | Gibco | PMG8041 | Component of tumosphere media |

| N-2 Supplements (100X) | Gibco | 17502048 | Component of tumosphere media |

| PBS | Gibco | 10010023 | Component of FACS buffer and used for washing cells |

| Fluriso (Isofluornae) anesthetic agent | MWI Vet Supply | 502017 | Anesthetic reagent for animals |

| Accutase cell dissociation reagent | Gibco | A1110501 | Detach adherent cells and dissociate tumorspheres |

| Matrigel membrane matrix | Corning | CB40234 | Provides support to trasplanted cells |

| Horse Serum | Life Technologies | 16050114 | Component of cell isolation media |

| Collagenase, Type II | Life Technologies | 17101015 | Tissue digestion enzyme |

| Dispase II, protease | Life Technologies | 17105041 | Tissue digestion enzyme |

| EDTA | ThermoFisher | S312500 | Component of FACS buffer |

| FxCycle™ Violet Stain | Life Technologies | F10347 | Discriminate live and dead cells |

| Trypan blue | ThermoFisher | 15250061 | Discriminate live and dead cells |

| Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent | ThermoFisher | L3000015 | Transfection Reagent |

| Recombinant mouse Flt-3 Ligand Protein | R&D Systems | 427-FL-005 | Recombinant protein |

| pEGFP-C1 | Addgene | 6084–1 | GFP plasmid |

| Celigo | Nexcelom | Celigo | Microwell plate based image cytometer for adherent and suspension cells |

| FACSAria II Flow Cytometry | BD Biosciences | 650033 | Fluorescent activated cell sorter |

| Neomycin-Polymyxin B Sulfates-Bacitracin Zinc Ophthalmic Ointment | MWI Vet Supply | 701008 | Eyes ointment |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

This work was supported by the Ellison Medical Foundation grant AG-NS-0843–11, and the NIH Pilot Grant within the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA030199 to A.S.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Dagogo-Jack I. & Shaw AT Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 15 (2), 81–94, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wicha MS, Liu S. & Dontu G. Cancer stem cells: an old idea--a paradigm shift. Cancer Research. 66 (4), 1883–1890; discussion 1895–1886, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ & Clarke MF Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proceedings National Academy of Science of the United States of America. 100 (7), 3983–3988, (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oishi N, Yamashita T. & Kaneko S. Molecular biology of liver cancer stem cells. Liver Cancer. 3 (2), 71–84, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crous AM & Abrahamse H. Lung cancer stem cells and low-intensity laser irradiation: a potential future therapy? Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 4 (5), 129, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomao F. et al. Investigating molecular profiles of ovarian cancer: an update on cancer stem cells. Journal of Cancer. 5 (5), 301–310, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhan HX, Xu JW, Wu D, Zhang TP & Hu SY Pancreatic cancer stem cells: new insight into a stubborn disease. Cancer Letters. 357 (2), 429–437, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharpe B, Beresford M, Bowen R, Mitchard J. & Chalmers AD Searching for prostate cancer stem cells: markers and methods. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 9 (5), 721–730, (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lapidot T, et al. l. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 367 (6464), 645–648, (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C-H, Yu C-C, Wang B-Y & Chang W-W Tumorsphere as an effective in vitro platform for screening anti-cancer stem cell drugs. Oncotarget. 7 (2), 1215–1226, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sultan I, Qaddoumi I, Yaser S, Rodriguez-Galindo C. & Ferrari A. Comparing adult and pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1973 to 2005: an analysis of 2,600 patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 27 (20), 3391–3397, (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blum JM et al. Distinct and overlapping sarcoma subtypes initiated from muscle stem and progenitor cells. Cell Reports. 5 (4), 933–940, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin BP et al. Evidence for an unanticipated relationship between undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 19 (2), 177–191, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller C. et al. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas in conditional Pax3:Fkhr mice: cooperativity of Ink4a/ARF and Trp53 loss of function. Genes & Development. 18 (21), 2614–2626, (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tremblay AM et al. The Hippo transducer YAP1 transforms activated satellite cells and is a potent effector of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma formation. Cancer Cell. 26 (2), 273–287, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatley ME et al. A mouse model of rhabdomyosarcoma originating from the adipocyte lineage. Cancer Cell. 22 (4), 536–546, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drummond CJ et al. Hedgehog Pathway Drives Fusion-Negative Rhabdomyosarcoma Initiated From Non-myogenic Endothelial Progenitors. Cancer Cell. 33 (1), 108–124 e105, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almazan-Moga A. et al. Hedgehog Pathway Inhibition Hampers Sphere and Holoclone Formation in Rhabdomyosarcoma. Stem Cells International. 2017 7507380, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter D. et al. CD133 positive embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma stem-like cell population is enriched in rhabdospheres. PLoS One. 6 (5), e19506, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciccarelli C. et al. Key role of MEK/ERK pathway in sustaining tumorigenicity and in vitro radioresistance of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma stem-like cell population. Molecular Cancer. 15 16, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deel MD et al. The Transcriptional Coactivator TAZ Is a Potent Mediator of Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma Tumorigenesis. Clinical Cancer Research. 24 (11), 2616–2630, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boscolo Sesillo F, Fox D. & Sacco A. Muscle Stem Cells Give Rise to Rhabdomyosarcomas in a Severe Mouse Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Cell Reports. 26 (3), 689–701 e686, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamberlain JS, Metzger J, Reyes M, Townsend D. & Faulkner JA Dystrophin-deficient mdx mice display a reduced life span and are susceptible to spontaneous rhabdomyosarcoma. The FASEB Journal. 21 (9), 2195–2204, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessel S. et al. High-Throughput 3D Tumor Spheroid Screening Method for Cancer Drug Discovery Using Celigo Image Cytometry. SLAS Technology. 22 (4), 454–465, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson S, Chen H. & Lo PK In vitro Tumorsphere Formation Assays. Bio-Protocol. 3 (3), (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu ,ZW et al. l. A novel three-dimensional tumorsphere culture system for the efficient and low-cost enrichment of cancer stem cells with natural polymers. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 15 (1), 85–92, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi S. Downstream molecular pathways of FLT3 in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia: biology and therapeutic implications. Jornal of Hematology and Oncology. 4 13, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laouar Y, Welte T, Fu XY & Flavell RA STAT3 is required for Flt3L-dependent dendritic cell differentiation. Immunity. 19 (6), 903–912, (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogawa M, Bergsagel DE & McCulloch EA Differential effects of melphalan on mouse myeloma (adj. PC-5) and hemopoietic stem cells. Cancer Research. 31 (12), 2116–2119, (1971). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamburger AW & Salmon SE Primary bioassay of human tumor stem cells. Science. 197 (4302), 461–463, (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamburger AW The human tumor clonogenic assay as a model system in cell biology. The International Journal of Cell Cloning. 5 (2), 89–107, (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jimenez-Hernandez LE et al. NRP1-positive lung cancer cells possess tumor-initiating properties. Oncology Reports. 39 (1), 349–357, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh SK et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 432 (7015), 396–401, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimlin LC, Casagrande G. & Virador VM In vitro three-dimensional (3D) models in cancer research: an update. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 52 (3), 167–182, (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salerno M. et al. Sphere-forming cell subsets with cancer stem cell properties in human musculoskeletal sarcomas. International Journal of Oncology. 43 (1), 95–102, (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]