Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- DPP-4

dipeptidyl peptidase-4

We read with interest the review by Bouhanick et al. [1] which discussed the association between diabetes mellitus and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Particularly, the authors have summarized the available evidence on the use of several classes of glucose-lowering agents in patients with COVID-19, and they postulated that dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors could influence the course of COVID-19 via their anti-inflammatory actions. While the medical community had been struggling to search for a potential cure in patients with COVID-19, we believe that DPP-4 inhibitors should be trialled for their efficacy to reduce the risk of death and/or severe disease in this patient population. Since there have been few studies which addressed the issue, we aimed to perform a meta-analysis to summarize the overall effect of DPP-4 inhibitors on the clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and medRxiv (a preprint repository) databases, up to 17 November 2020, for studies of any design evaluating the risk of a fatal or severe course of COVID-19 among DPP-4 inhibitor users compared to non-DPP-4 inhibitors users, with the following keywords and their MeSH terms: “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “dipeptidyl-peptidase-4”, “DPP-4”, and “gliptin”, without language restrictions. The inclusion criteria were studies that investigated the preadmission use of DPP-4 inhibitors on the risk of a fatal or severe course of COVID-19 and reported adjusted measures of association. We excluded editorials or narrative reviews without original data. In addition, studies that provided no adjusted estimation were also excluded. Each included article was independently evaluated by two authors (CSK and SSH) who extracted the study characteristics and adjusted measures of effect. The quality of observational studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. The outcome of interest was the development of a fatal or severe course of COVID-19. Adjusted odds ratios or relative risks and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals from each study were pooled in a random-effects model using Meta XL, version 5.3 (EpiGear International, Queensland, Australia) to produce pooled odds ratio and 95% confidence interval. The I2 statistic was performed to estimate the magnitude of heterogeneity.

We were able to retrieve six studies [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7] of observational design that corresponded to our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Study characteristics are depicted in Table 1 . Altogether, the meta-analysis included over 1,531 patients with COVID-19. Except the study by Dalan et al. [6] which is of moderate quality (Newcastle-Ottawa scale of 5), the remaining five studies [3], [4], [5], [7], [8] are deemed good quality with a Newcastle-Ottawa scale of 7 to 8. There was non-uniformity in the definition of the severe disease in patients with COVID-19 utilized across the six included studies. In both the studies by Chen et al. [2] and Yan et al. [6], severe illness was defined based on the diagnosis and treatment plan for COVID-19 issued by the National Health Commission of China.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Country | Design | Total number of patients | Age (median/mean unless otherwise specified) | Severe/Fatal course of illnessa |

Covariates adjustment | NOS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPP-4 inhibitors users (n/N; %) | Non-DPP-4 inhibitors users (n/N; %) | Adjusted estimate (95% CI) | |||||||

| Chen et al. [2] | China | Retrospective, single center | 120 | DPP-4 inhibitor users = 66.0 Non-DPP-4 inhibitor users = 65.0 |

N/A | N/A | OR = 1.81 (0.51-6.37) |

Age, serum albumin level, serum creatinine level, C-reactive protein level, blood glucose level | 8 |

| Dalan et al. [5] | Singapore | Retrospective, single center | 76 | N/A | N/A | N/A | RR = 5.14 (1.49-17.70) |

Age, sex, ethnicity, use of anti-hypertensive medications, other diabetes Medications, statins, haemoglobin A1c, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index |

7 |

| Kim et al. [3] | Korea | Retrospective, multicenter | 235 | All patients = 68.3 | N/A | N/A | Severe illness: OR = 1.05 (0.44-2.49) Mortality: OR = 1.47 (0.45-4.78) |

Age, sex, comorbidities | 7 |

| Rhee et al. [4] | Korea | Retrospective database review | 832 | DPP-4 inhibitor users = 63.7 Non-DPP-4 inhibitor users = 61.0 |

25/569 (4.4) | 9/263 | OR = 0.36 (0.14-0.97) |

Age, sex, comorbidities, co-medications | 7 |

| Yan et al. [6] | China | Retrospective, multicenter | 58 | All patients = 49.2 (14.2) | 1/6 (16.7) | 20/52 (38.5) | OR = 0.32 (0.02-2.18) |

Age, sex, body mass index | 5 |

| Pérez-Belmonte [7] | Spain | Retrospective, multicenter | 210 | DPP-4 inhibitor users = 80.0 Non-DPP-4 inhibitor users = 79.4 |

45/105 (42.9) | 42/105 (40.0) | OR = 1.12 (0.65-1.95) |

Age, sex, history of smoking, comorbidities, Barthel Index score, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, co-medications, admission blood glucose, serum creatinine, transaminase levels | 7 |

CI confidence interval; DPP-4 dipeptidyl peptidase-4; NOS Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; OR odds ratio; RR relative risk.

In both the studies by Chen et al. [2] and Yan et al. [6], severe illness was defined based on the Diagnosis and Treatment Plan for COVID-19 issued by the National Health Commission of China. In the study by Kim et al. [3], severe illness was defined based on the use of high-flow nasal cannula, mechanical ventilation, continuous renal replacement therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and admission to intensive care units. In the study by Rhee et al. [4], severe illness was defined based on the presence of procedure code for endotracheal intubation or mechanical ventilation, or the charge of an intensive care unit management fee. In the study by Dalan et al. [5], severe illness was defined based on admission to intensive care units. In the study by Pérez-Belmonte et al. [7], severe illness was defined based on admission to intensive care units, the use of invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation, or in-hospital death.

In the study by Kim et al. [3], severe illness was defined based on the use ofhigh-flow nasal cannula, mechanical ventilation, continuous renal replacement therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and admission to intensive care units. In the study by Rhee et al. [4], severe illness was defined based on the presence of procedure code for endotracheal intubation or mechanical ventilation, or the charge of an intensive care unit management fee. In the study by Dalan et al. [5], severe illness was defined based on admission to intensive care units. In the study by Pérez-Belmonte et al. [7], severe illness was defined based on admission to intensive care units, the use of invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation, or in-hospital death.

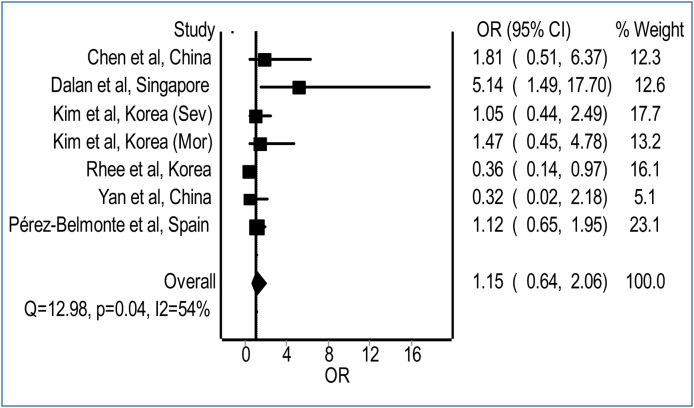

Our meta-analysis revealed no significant difference in the risk for the development of a fatal or severe course of illness with preadmission use of DPP-4 inhibitors in patients with COVID-19, relative to non-use of DPP-4 inhibitors (Fig. 1 ; pooled odds ratio = 1.15; 95% confidence interval 0.64-2.06; I2 = 54%). The potential role of DPP-4 inhibitors in patients with COVID-19 has been a subject of ongoing debate. DPP-4 inhibitors including gemigliptin, linagliptin, and evogliptin, have demonstrated their potential in the in silico molecular docking analysis to inhibit the main protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, which plays a pivotal role in viral gene expression and replication [8]. Nevertheless, DPP-4 plays also a vital role in the regulation of the immune system via activation of T cells through the nuclear factor-κB pathway and thus its inhibition may adversely affect the immune response to viral infection, especially when lower levels of T cells have been reported to correlate with severity of COVID-19 [9], [10].

Figure 1.

Pooled odds for a fatal or severe course of illness in COVID-19 patients with preadmission use of DPP-4 inhibitors relative to non-use of DPP-4 inhibitors. (heterogeneity: I2 = 54%; P = 0.04). CI: confidence interval; DPP-4: dipeptidyl peptidase-4; OR: odds ratio.

Our meta-analysis had a moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 54%), contributed substantially by the study from Dalan et al. [5] due to wide confidence interval reported. Although our meta-analysis was limited by a relatively small number of patients included and wide confidence interval, it does indicate no safety signal thus far associated with the use of DPP-4 inhibitors in patients with COVID-19. Whether DPP-4 inhibitors could be beneficial to the prognosis of patients with COVID-19 requires further confirmation in large-scale prospective studies.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Bouhanick B., Cracowski J.L., Faillie J.L. French Society of Pharmacology, Therapeutics (SFPT). Diabetes and COVID-19. Therapie. 2020;75(4):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y., Yang D., Cheng B., Chen J., Peng A., Yang C. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with diabetes and COVID-19 in association with glucose-lowering medication. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1399–1407. doi: 10.2337/dc20-0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim M.K., Jeon J.H., Kim S.W., Moon J.S., Cho N.H., Han E., et al. The clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with moderate-to-severe coronavirus disease 2019 infection and diabetes in Daegu, South Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(4):602–613. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2020.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhee S.Y., Lee J., Nam H., Kyoung D., Kim D.J. Effects of a DPP-4 inhibitor and RAS blockade on clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes and COVID-19. Preprint. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.4093/dmj.2020.0206. [2020.05.20.20108555] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalan R., Ang L.W., Tan W.Y.T., Fong S.W., Tay W.C., Chan Y.H., et al. The association of hypertension and diabetes pharmacotherapy with COVID-19 severity and immune signatures: an observational study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa098. [pvaa098] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan H., Valdes A.M., Vijay A., Wang S., Liang L., Yang S., et al. Role of drugs used for chronic disease management on susceptibility and severity of COVID-19: a large case-control study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108(6):1185–1194. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pérez-Belmonte L.M., Torres-Peña J.D., López-Carmona M.D., Ayala-Gutiérrez M.M., Fuentes-Jiménez F., Huerta L.J., et al. Mortality and other adverse outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus admitted for COVID-19 in association with glucose-lowering drugs: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):359. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01832-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao P.P.N., Pham A.T., Shakeri A., El Shatshat A. Drug repurposing: dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP4) inhibitors as potential agents to treat SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCov) infection. Preprint. Research Square. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-28134/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klemann C., Wagner L., Stephan M., von Hörsten S. Cut to the chase: a review of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase-4's (DPP4) entanglement in the immune system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;185(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/cei.12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang M., Guo Y., Luo Q., et al. T-cell subset counts in peripheral blood can be used as discriminatory biomarkers for diagnosis and severity prediction of coronavirus disease 2019. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(2):198–202. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]