Abstract

Aims

In Fabry cardiomyopathy, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a very rare finding, with few cases reported and successfully treated with cardiac surgery. In our population of patients with Fabry disease and severe left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) at the time of diagnosis, we observed an evolution towards a midventricular obstructive phenotype.

Methods and results

We present a case series of three classically affected Fabry male patients with significant diagnostic delay and severe cardiac involvement (maximal wall thickness >20 mm) at first evaluation. All patients developed midventricular obstructive form over time despite prompt initiation and optimal compliance to enzyme replacement therapy. The extension and distribution of the LVH, involving the papillary muscles, was the main mechanism of obstruction, unlike the asymmetric septal basal hypertrophy and the mitral valve abnormalities commonly seen as substrate of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Conclusions

Fabry cardiomyopathy can evolve over time towards a midventricular obstructive form due to massive LVH in classically affected men with significant diagnostic delay and severe LVH before enzyme replacement therapy initiation. This newly described cardiac phenotype could represent an adverse outcome of the disease.

Keywords: Fabry disease, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Cardiomyopathy, Prognosis, Obstruction

Fabry disease (FD) is an X‐linked inherited disorder of glycosphingolipid metabolism, in which the deficient or absent lysosomal α‐galactosidase A activity leads to the accumulation of globotriaosylceramide in different organs, including the heart. 1 Cardiac involvement affects about 70% of FD patients, and the hallmark of Fabry cardiomyopathy is left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). LVH is usually concentric in FD, but asymmetric septal hypertrophy has been reported in as much as 5% of cases. 1 Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) is common in HCM, while it is rare in FD. However, some cases of FD patients with LVOTO have been reported and successfully treated by surgery as HCM, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 while midventricular obstruction is anecdotally described. 6 , 7

Here, we report three cases of severe FD cardiomyopathy evolving into obstructive forms, characterized by midventricular obstruction rather than LVOTO, mainly caused by massive LVH involving the papillary muscles.

Table 1 summarizes the main clinical characteristics of patients. All patients were male with no relevant co‐morbidities, except for the multiorgan Fabry‐related manifestations. They were all affected by classic form of the disease, and they were diagnosed with Fabry after the 4th decade of life, when significant LVH had already developed. They all started enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) as soon as the diagnosis of FD was made and showed excellent compliance to ERT. LVH increased over time and determined LV gradient respectively 2 years after our first evaluation in Case 1, 6 years in Case 2, and 6 years in Case 3. The main echocardiographic features of the three patients recorded when the midventricular obstruction was firstly documented are presented in Table 2 . The three patients had major cardiac events before the development of the LV obstruction. Cases 1 and 2 were symptomatic for minimal effort angina (Canadian Class III) with evidence in one case of severe coronary microvascular dysfunction, 8 and both were admitted to local hospitals for myocardial infarction with non‐obstructive coronary arteries at coronary angiography. Case 2 underwent pacemaker implantation for advanced atrioventricular block episodes documented at 24 h Holter monitoring. Case 3 had good functional capacity with no signs or symptoms of heart failure, but 3 years after our first evaluation, he was admitted to the hospital for syncope: a complete third‐degree atrioventricular block was documented, and pacemaker was implanted. All patients were on beta‐blocker, which was well tolerated but had no significant impact on obstruction, and two of them were also on angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; right ventricular pacing with short atrioventricular delay was tried in the two patients with pacemaker, with no major effect. The midventricular obstruction had an impact on patient's clinical status only in Case 1 (New York Heart Association class progression), while Cases 2 and 3 did not seem significantly affected by the development of the obstruction, because Case 2 was symptomatic for angina and Case 3 was not symptomatic at all and continued his normal physical activity (amateur cycling).

Table 1.

Main clinical features and extracardiac manifestations of patients

| Variables | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | M | M |

| Age at diagnosis | 49 | 48 | 50 |

| Mutation | c.801 + 1G > T | c.747C > A | c.548G > C |

| α‐GAL A activity on leucocytes, nmol/mL/h | 3.38 ± 0.17 | 4.19 ± 0.75 | 4.61 ± 0.62 |

| NYHA at first evaluation | II | I | I |

| Kidney | Kidney transplant a | No | Kidney transplant a |

| Brain | No | No | No |

| Neuropathy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Skin | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Yes | No | No |

| Eye | No | Yes | No |

| MSSI | 57 | 40 | 51 |

| Beta‐blockers | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ERT duration, years | 4 | 9 | 10 |

ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; GAL, galactosidase; MSSI, Mainz Severity Score Index; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Immunosuppressive therapy in these patients did not include tacrolimus.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic features of the three patients recorded when the midventricular obstruction was firstly documented

| Variables | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Septal WT, mm | 26 | 30 | 23 |

| Posterior WT, mm | 22 | 19 | 20 |

| Maximal WT, mm | 30 | 30 | 29 |

| LVMi, g/m2 | 367 | 354 | 323 |

| Midventricular Gmax, mmHg | 71 | 75 | 56 |

| LVEF, % | 61 | 65 | 51 |

| Septal S', cm/s | 3.3 | 5.9 | 3.4 |

| Lateral S', cm/s | 4.3 | 4.4 | 3.4 |

| E/e' ratio | 18.5 | 13 | 20 |

| LV GLS a , % | −9 | −11.3 | −12 |

| RVWT, mm | 8 | 7 | 13 |

| TAPSE, mm | 22 | 26 | 16 |

| RVFAC, % | 51 | 45 | 35 |

| RV S', cm/s | 10 | 18 | 8.5 |

E/e', transmitral early peak velocity/tissue Doppler early diastolic mitral annulus velocity; lateral S', tissue Doppler mitral annular systolic velocity at lateral corner; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LV GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal strain; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; midventricular Gmax, left midventricular peak systolic gradient; RVFAC, right ventricular fractional area change; RV S', right ventricular tissue Doppler systolic velocity; RVWT, right ventricular wall thickness; septal S', tissue Doppler mitral annular systolic velocity at septal corner; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; WT, wall thickness.

Speckle tracking analysis performed with 2D Cardiac Performance Analysis© by TomTec‐ArenaTM.

To our knowledge, this is the first evidence of the progression towards a severe form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy characterized by intraventricular obstruction in classically affected FD male patients with significant LVH but no obstruction at baseline, despite optimal compliance to ERT. The novelty of our report is that it uncovers a non‐previously described subset of Fabry patients in whom the disease may easily be mistaken for sarcomeric HCM.

In our population, this evolution occurred in three patients (10% of all patients with cardiac involvement and 21% of classically affected men), all with significant diagnostic delay, accountable as at least 30 years, and consequent therapeutic delay with ERT started when maximal wall thickness was already >20 mm (Figure 1 ). In all three cases, the obstruction took place at the mid‐cavity level, with a mechanism different from the LVOTO usually observed in classic HCM, 3 which is mainly related to asymmetric basal septal hypertrophy and systolic anterior mitral leaflet movement, often associated with abnormalities of the mitral valve and subvalvular apparatus. Indeed, in our patients, no abnormalities in mitral valve (elongated leaflets, abnormal/accessory chordae, and systolic anterior movement) were documented, suggesting that the mitral valve apparatus does not concur to the mechanism of obstruction. The obstruction occurred at midventricular level and was mainly caused by the massive LVH and severe hypertrophy of papillary muscles, leading to LV cavity obliteration in systole as shown in Figure 2 . All the three patients were evaluated by a cardiac surgeon highly experienced in HCM surgery (P. F.) to assess a possible surgical approach to relief obstruction and enlarge the LV cavity. However, considering the advanced stage of the cardiac involvement and the clinical status (two patients mainly symptomatic for angina and one patient asymptomatic), the two symptomatic patients were referred to a cardiac transplant programme for evaluation.

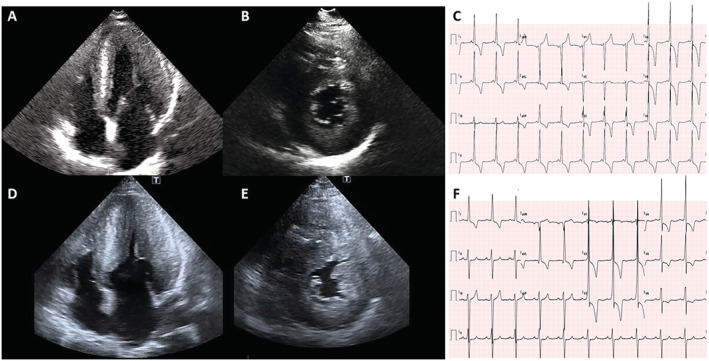

Figure 1.

Example of echocardiographic and electrocardiographic changes over time in one patient (Case 2). 2D echocardiography: (A) Apical four‐chamber and (B) parasternal short‐axis view diastolic frames recorded at the time of diagnosis, showing severe left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). (D–E) The same views acquired after 6 years show a dramatic increase in left ventricular wall thickness towards a massive form of LVH, especially at the papillary muscles level. (C) Twelve‐lead electrocardiogram: At baseline, short PR and signs of LVH with prominent repolarization abnormalities are evident. (F) The electrocardiogram performed the same day in which the LV obstruction was documented at echocardiography shows an increased PR (192 from 122 ms), intraventricular conduction delay, left anterior fascicular block, and worsening of the repolarization abnormalities.

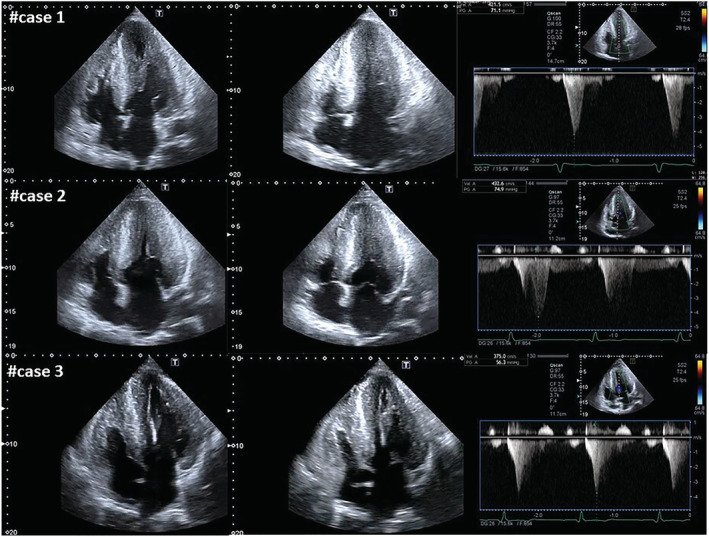

Figure 2.

2D echocardiography showing apical four‐chamber diastolic and systolic frames along with the maximum systolic gradient recorded at continuous‐wave Doppler. Massive biventricular hypertrophy is evident in all the three cases [left ventricular (LV) maximal wall thickness ~30 mm] with severe hypertrophy of papillary muscles, leading to LV cavity obliteration in systole and to LV midventricular obstruction with peak systolic gradient respectively of 71 mmHg in Case 1, 75 mmHg in Case 2, and 56 mmHg in Case 3.

In conclusion, FD cardiomyopathy can evolve over time towards a midventricular obstructive form due to massive LVH. In our experience, this evolution occurred in classically affected men with a significant diagnostic delay and severe LVH before ERT initiation. Patients with these characteristics at baseline must have a close follow‐up and be promptly referred to a cardiac surgeon experienced in HCM surgery and/or to a transplant programme. This newly described cardiac phenotype could represent an adverse outcome of the disease.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

Graziani, F. , Lillo, R. , Panaioli, E. , Spagnoletti, G. , Pieroni, M. , Ferrazzi, P. , Camporeale, A. , Verrecchia, E. , Sicignano, L. L. , Manna, R. , and Crea, F. (2021) Evidence of evolution towards left midventricular obstruction in severe Anderson–Fabry cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Failure, 8: 725–728. 10.1002/ehf2.13101.

References

- 1. Linhart A, Elliott PM. The heart in Anderson–Fabry disease and other lysosomal storage disorders. Heart 2007; 93: 528–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Geske JB, Jouni H, Aubry MC, Gersh BJ. Fabry disease with resting outflow obstruction masquerading as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cecchi F, Iascone M, Maurizi N, Pezzoli L, Binaco I, Biagini E, Fibbi ML, Olivotto I, Pieruzzi F, Fruntelata A, Dorobantu L, Rapezzi C, Ferrazzi P. Intraoperative diagnosis of Anderson–Fabry disease in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy undergoing surgical myectomy. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2: 1147–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calcagnino M, O'Mahony C, Coats C, Cardona M, Garcia A, Janagarajan K, Mehta A, Hughes D, Murphy E, Lachmann R, Elliott PM. Exercise‐induced left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in symptomatic patients with Anderson–Fabry disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 88–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meghji Z, Nguyen A, Miranda WR, Geske JB, Schaff HV, Peck DS, Newman DB. Surgical septal myectomy for relief of dynamic obstruction in Anderson–Fabry disease. Int J Cardiol 2019; 292: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cianciulli TF, Saccheri MC, Fernández SP, Fernández CC, Rozenfeld PA, Kisinovsky I. Apical left ventricular hypertrophy and mid‐ventricular obstruction in Fabry disease. Echocardiography 2015; 32: 860–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nishizawa S, Osamura T, Takechi N, Kusuoka S, Furukawa K. Mid‐ventricular obstruction occurred in hypertrophic left ventricle of heterozygous Fabry's disease—favorable effects of cibenzoline: a case report. J Cardiol Cases 2011; 4: e133–e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Graziani F, Lillo R, Panaioli E, Spagnoletti G, Bruno I, Leccisotti L, Marano R, Manna R, Crea F. Massive coronary microvascular dysfunction in severe Anderson–Fabry disease cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019; 12: e009104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]