Abstract

Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is the respiratory viral infection caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2). Despite being a respiratory illness, COVID-19 is found to increase the risk of venous and arterial thromboembolic events. Indeed, the link between COVID-19 and thrombosis is attracting attention from the broad scientific community. In this review we will analyze the current available knowledge of the association between COVID-19 and thrombosis. We will highlight mechanisms at both molecular and cellular levels that may explain this association. In addition, the article will review the antithrombotic properties of agents currently utilized or being studied in COVID-19 management. Finally, we will discuss current professional association guidance on prevention and treatment of thromboembolism associated with COVID-19.

1. Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) resulted in global pandemic in early 2020. The World Health Organization (WHO) designated the name COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease of 2019) as the official name of the diseases caused by SARS-CoV2. First reported in Wuhan China in late 2019, the total confirmed COVID-19 cases worldwide have surpassed 49 million with more than a million of global death in eleven months (coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). From the name of its causative virus, COVID-19 is a primarily respiratory disease that, in severe cases, can lead to pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). However, several non-respiratory presentations are being manifested in COVID-19 patients among which are venous and arterial thromboembolic events.

Thromboembolic complications have been reported in COVID-19 patients by different groups (just to mention few, [1], [2], [3], [4]). Importantly, various organs are affected by COVID-19 induced coagulopathy, including the vasculature of lungs [1], legs [3], spleen [2], heart [5]and brain [6]. These complications are usually associated with multiorgan failure and high mortality in severe cases of the diseases [7]. The current clinical data indicate that both pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) are the most frequently noted thrombotic events in COVID-19 [4]. Intriguingly, the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains to be high in hospitalized patients despite anticoagulation prophylaxis [8], [9], [10], [12]. Indeed, the data are rapidly emerging and at the time of writing this article, the rate of venous thromboembolic events was estimated as high as 25 to 30%, particularly in critically ill and mechanically ventilated patients [13]. Other thrombotic complications were also reported including stroke, acute limb ischemia and acute coronary syndromes [6,14,15]. Both acute ischemic stroke and myocardial injury are reported in up to 5% and 20% in hospitalized patients, respectively [16,17]. The multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) as a result of SARS-CoV2 infection may also increase, alarmingly, the risk of coagulopathy in the pediatric population [18]. In this review, we will summarize a number of mechanisms at the molecular/cellular level by which SARS-CoV2 infection may cause thrombosis. Also, we will review the current pharmacotherapy and professional association guidance on prevention and treatment of thromboembolism associated with COVID-19.

2. COVID-19 downregulating ACE2; respiratory or vascular disease

SARS-CoV2 attaches to human cells through binding of its spike protein (S-protein) to the human angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor [19]. Interestingly, ACE2 expression is found to be higher in the ciliated cells of the nose compared to bronchi indicating that the nose is most likely the initial site of viral entry [20]. However, ACE2 is not only expressed in nasopharyngeal and lung cells but also in blood vessels, heart, kidney, testicle and brain [21]. In fact, this carboxypeptidase, ACE2, was first cloned from human heart and found to be highly expressed throughout the endothelia of coronary and renal blood vessels [22]. This may suggest important biological functions of ACE2 in cardiovascular system. Indeed, a major role of ACE2 among others is to inactivate angiotensin II by proteolytically converting it to angiotensin 1-7 (reviewed in [23]). This thus places ACE2 in a critical position as a negative regulator of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS).

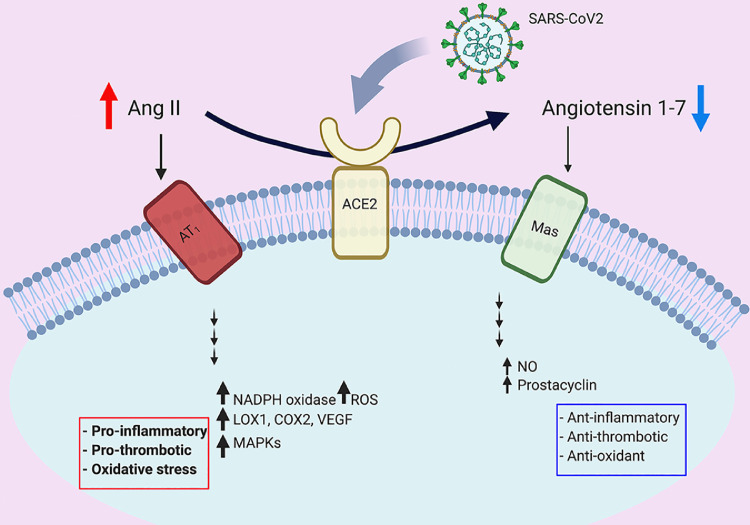

Many reports indicate that SARS-CoV2 entry is associated with downregulating ACE2 activity (reviewed in [24]), suggesting that RAAS may be augmented in COVID-19 patients (Fig. 1 ). Consistently, two clinical trials using angiotensin II receptor (AT1) blocker (losartan) to ameliorate COVID-19 related complications are underway (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04312009 and NCT04311177). The higher affinity of SARS-CoV2 to human ACE2 compared to other coronaviruses [25], and the downregulation of ACE2 in COVID-19 may explain the peculiar cardiovascular manifestations seen in vulnerable patients [26]. On the other hand, ACE2 expression may be upregulated in patients taking ACE inhibitors or AT1 blockers [27,28], thus raising the concern of facilitating SARS-Cov2 entry in these patients. However, the BRACE CORONA trial has provided clinical data showing that there is no clinical benefit in routinely withholding these agents in hospitalized patients with mild to moderate infection [29,30].

Fig. 1.

Dysregulated renin angiotensin aldosterone system in COVID-19. SARS-CoV2 has higher affinity to ACE2 receptor compared to other coronaviruses. ACE2 is a carboxypeptidase that converts angiotensin II (Ang II) to angiotensin 1-7. The binding between the spike protein (S-protein) of the virus and ACE2 is associated with downregulation of ACE2 activity. In its turn, this will lead to augmentation of Ang II signaling and pro-thrombotic pathways. On the other hand, the angiotensin 1-7 signaling which mediates anti-thrombotic pathways is diminished.

Intriguingly, some COVID-19 patients presented with thrombotic events had no or mild respiratory symptoms [6,26]. These cardiovascular sequalae led some experts to consider COVID-19, even in the absence of respiratory symptoms, in the differential diagnosis of thromboembolism and acute coronary syndrome [31].

3. Potential mechanisms of COVID-19 induced thrombosis

The strong association between COVID-19 and vascular coagulopathy may suggest that there are multiple molecular pathways that are dysregulated during the clinical progression of the diseases and thus contributing to the associated thrombosis. Clearly RAAS augmentation, as a consequence of ACE2 downregulation, is an important factor [32]. In addition, the dysregulated immune/inflammatory response is a well-studied risk factor for blood coagulation [33]. One cannot rule out a “double whammy” effect in which both factors may additively or synergistically increase thrombosis risk in COVID-19 patients. Below we will summarize some potential mechanisms that may explain the association between COVID-19 and coagulopathy at molecular/cellular levels. However, more investigations are warranted in order to exploit these findings in therapeutics.

3.1. Dysregulated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and the role of ACE2

As described above, ACE2 converts angiotensin II to angiotensin 1-7. SARS-CoV2 uses ACE2 to internalize human cells and thus may lead to reduce ACE2 activity [24]. Consequently, this will result in increased angiotensin II and decreased angiotensin 1-7. It is worth noting that whereas angiotensin II has pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic effects, angiotensin 1-7 is now recognized as an important anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic peptide [34,35]. Angiotensin 1-7 binds Mas receptors on endothelium and increases nitric oxide and prostacyclin production, thus inhibits platelets activation [36] (Fig. 1). It has been shown that ACE2 is widely expressed on endothelial cells and direct SARS-CoV2 infection of endothelia is possible [37]. Therefore, dysregulated RAAS in vasculature of COVID-19 patients may initiate a cascade of events that lead to increased coagulopathy, as summarized below.

3.1.1. Oxidative stress damage

In addition to its immediate physiological effect in vasoconstriction, angiotensin II has been shown to be a potent mediator of oxidative stress damage through rapid generation of reactive oxygen species mediated by NADPH oxidases (reviewed in [35]). On the other hand, angiotensin 1–7 may play a pivotal antioxidant role by induction of nitric oxide synthesis/release from endothelial cells [36]. Both accumulation of reactive oxygen species and deficiency of nitric oxide are expected to have various detrimental effects on endothelium. Despite limited clinical data in COVID-19, oxidative stress damage to the infected endothelium may play a key role in severe SARS-CoV2 infection. Vitamin C, a potent antioxidant, has emerged as a potential therapy due to its potential benefits in COVID-19 [38]. However, the evidence whether these benefits are directly related to vitamin C antioxidant properties or other undefined mechanisms is still lacking.

3.1.2. Endothelial dysfunction

Dysregulated RAAS can not only cause endothelial damage via oxidative stress as described above, but also through various pathways including overexpression of LOX-1, COX-2 and VEGF in the endothelium (just to name a few) [39]. There is a strong relationship between endothelial dysfunction and thrombotic events in various pathologies (reviewed in [40]. The glycocalyx in healthy endothelium plays an important role in preventing the clotting cascades and glycocalyx degradation, seen in endothelial dysfunction, may trigger various clotting cascades [41]. Endothelial dysfunction is also associated with endothelial expression of many prothrombotic molecules and receptors including P-selectins [42], angiopoietin-2 [43] and endothelin-1 [44], which are active players in thrombosis. In addition, several studies suggest that endothelial damage/dysfunction is a critical component of thrombin generation and activation via the release of the procoagulant factor, fVIII [45], [46], [47].

Ackerman et al., examined lungs from COVID-19 and influenza A patients who died from associated ARDS [48]. This comparison revealed very interesting findings and showed distinctive vascular features between SARS-CoV2 and influenza H1N1 infections. COVID-19 lungs displayed more severe endothelial damage and disrupted endothelial membranes in comparison to those from influenza. Histological analyses of blood vessels showed widespread thrombosis and microangiopathy. Despite ARDS was the common cause of death in both groups, angiogenesis and alveolar capillary microthrombi in COVID-19 were 3 to 9 times as prevalent as in influenza, respectively [48]. Moreover, epidemiological data show that COVID-19 patients with conditions associated with preexisting endothelial dysfunction such as aging, hypertension, obesity and diabetes are more frequently admitted to intensive care units and have poor prognosis [49]. These observations strongly suggest that endothelial dysfunction and subsequent activation of the clotting cascade are more common to the pathogenesis of COVID-19.

3.1.3. Activation of von Willebrand factor

Endothelial damage, in general, seems to contribute to the pathophysiology of COVID-19. This may also suggest a potential role of von Willebrand Factor (vWF) in COVID-19 associated coagulopathy. In addition to being in plasma, vWF is deposited on subendothelial spaces where it is associated with type VI collagen [50]. Upon endothelial damage, subendothelial vWF is released, further multimerized by disulfide bonds and activated by exposing both platelet-binding and collagen-binding domains [43]. Therefore, active vWF multimers act as molecular glues that stick platelets and subendothelial collagens together, activating platelets aggregation and thrombosis.

In a single-center cross-sectional study, vWF antigen and activity were found to be three times higher in non- intensive care unit (ICU) COVID-19 patients compared to control group [51]. In ICU COVID-19 patients, vWF concentration/activity were further elevated in comparison to non-ICU cohort. Soluble thrombomodulin concentrations, another marker of endothelial damage, were also found to be associated with poor clinical outcomes and survival [51]. Despite some limitations, this study reports that vWF is also elevated in non-critically ill patients with COVID-19. Consequently, both critically and non-critically ill patients with COVID-19 may have higher thromboembolic risks [52,53]. The roles of dysregulated RAAS and vWF in COVID-19 associated thrombosis open potential therapeutic avenues for agents that interfere with this pathway. For example, N-acetylcysteine is reported to reduce intrachain disulfide bonds in large vWF multimers inside thrombi, thereby leading to their dissolution [54]. In fact, searching clinicaltrials.gov revealed three recruiting (NCT04374461, NCT04370288, NCT04279197) and two not-yet recruiting (NCT04455243, NCT04419025) clinical trials using N-acetylcysteine as a potential therapy to improve COVID-19 outcomes. Future will tell whether N-acetylcysteine is effective in improving COVID-19 outcomes by reducing the risk of thrombosis.

3.2. Dysregulated immune response

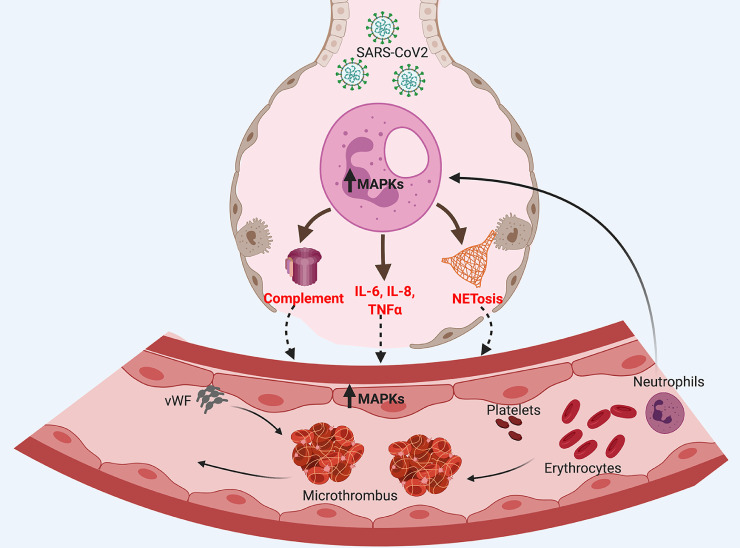

The immune response to SARS-CoV2 infection has not been fully understood. Several studies highlight changes in both innate and adaptive immunity in COVID-19 patients (reviewed in [55]). In severe cases, dysregulated innate immune response and the subsequent massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines “cytokine storm” clearly participate in the pathogenesis of the disease. In its turn, dysregulated innate immune response results in subsequent activation of various pathways “immunothrombosis” that may lead to blood coagulation (Fig. 2 ). Below we will summarize some of these pathways that have been described in COVID-19.

Fig. 2.

Dysregulated innate immune response in COVID-19. Innate immunity plays critical role as an early defense mechanism against microbial infection including SARS-CoV2. However, uncontrolled innate immune response elicited by overactivated neutrophils will initiate coagulopathic pathways. These pathways

may include excessive complement activation, cytokine storm and NETosis, each of which may cause thrombosis by various mechanisms.

3.2.1. Role of complement system

The complement system is an integral part of the innate immune response. In SARS-CoV1 murine model, a study reported increased complement activation and found that mice lacking the complement factor C3 exhibited less respiratory inflammation and better function [56]. Similar findings were also reported in mice infected with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [57]. Despite lacking experimental data in SARS-CoV2, the previous studies suggest that excessive complement activation contributes to the dysregulated immune response seen in coronaviruses infection.

There is mounting evidence of a crosstalk between the complement system and coagulation pathways. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, a rare genetic disorder of uncontrolled complement activation, is also characterized by thrombotic microangiopathy [58]. In fact, the complement system is capable of activating coagulation cascades through multiple mechanisms. The complement factors C3 and MAC directly activate platelets and induce platelet aggregation [59]. Similarly, complement factor C5a has been shown to stimulate the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, thereby promoting thrombosis [60]. Interestingly, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 was found to be elevated in both non-critically and critically ill patients with COVID-19 [51]. Last but not least, C5a increases tissue factor activity, which initiates the intrinsic pathway of coagulation [61]. In a preprint report of an ongoing study, COVID-19 patients with ARDS began to recover after treatment with recombinant anti-C5a antibody [62]. These observations suggest that further studies are warranted to investigate whether complement activation is involved in COVID-19 associated thrombosis. Accordingly, complement inhibition could be a potential target in COVID-19 treatment.

3.2.2. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)

Neutrophils are crucial players in innate immune response. One of their recently discovered and yet not fully understood function is releasing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in response to infection [63]. These structures comprise of extracellular scaffold of chromatin containing microcidal proteins designed to impede the dissemination of microbes in the blood [63]. Despite being efficient strategy to trap and kill microorganisms, excessive NETs (NETosis) formation can be harmful to the host. Several studies have implicated NETosis in various human pathologies including sepsis, vasculitis and thrombosis (reviewed in [64]).

The role of NETosis in inducing thrombosis is well established. For example, the NETs themselves contain various prothrombotic molecules, such as tissue factor, protein disulphide isomerase, factor XII, vWF and fibrinogen [65]. In addition, the extracellular DNAs released from NETs can directly activate platelets and lead to thrombus formation [65]. Circulating histones (major components of NETs) were also found to activate Toll-like receptors on platelets and promote thrombin generation [66]. In general, NETs tend to form larger aggregates that drive thrombosis by providing a scaffold for binding of activated platelets and erythrocytes and set up a vicious cycle propagating thrombus formation [67].

One report revealed higher levels of cell-free DNA, myeloperoxidase-DNA complex and citrullinated histone 3 (indicative markers of NETs) in sera of patients with COVID-19 as compared with the control group [68]. Interestingly, cell-free DNA and to a lesser extent myeloperoxidase-DNA complex and citrullinated histone 3 demonstrated significant correlation with other predictive tests for the severity of COVID-19 (e.g. C-reactive protein, D-dimer). Patients requiring mechanical ventilation had significantly higher levels of cell-free DNA and myeloperoxidase-DNA complex [68]. Emerging evidence indicates that NETosis contribute to increased thrombotic risks in COVID-19 [69]. COVID-19 sera were found to have higher levels of NETs carrying active tissue factor and promote thrombosis. Both NETosis and complement inhibitions, in-vitro, attenuated thrombin activation by COVID-19 sera [69]. In addition, the same study showed that NETs release is positively correlated with in-vivo, thrombotic potency in COVID-19 [69]. Accordingly, one can speculate that NETosis is a major driver of COVID-19 thrombosis; however, future studies are needed to investigate the effects of NETs inhibition in improving COVID-19 outcomes.

3.2.3. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) pathways

The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs; ERK, p38 and JNK) are considered central kinases which are early activated in innate immune response. MAPKs activation, likely mediated by Toll-like receptors signaling, induces expression of multiple genes that altogether regulate the innate and inflammatory response [70]. Furthermore, the roles of MAPKs in coronaviruses replication/infection have been elucidated. In vitro, SARS-CoV1 infection was associated with activation of multiple MAPKs pathways [71] and inhibition of MAPKs has been shown to inhibit murine coronavirus replication [72]. Given the similarities between those coronaviruses and SARS-CoV2, it is possible that MAPKs are activated in COVID-19. It is worth noting that MAPKs can also be activated in COVID-19 downstream of dysregulated RAAS as a result of ACE2 inhibition [73]. On the other hand, MAPKs pathways are significantly upregulated in various cardiovascular pathologies including thrombosis [74]. For example, activation of p38 signaling induces expression of tissue factor, a major initiator of coagulation, and mediates thrombotic events in anti-phospholipid syndrome [75]. Therefore, chronic activation of MAPKs pathways may also contribute to elevating the risk of thrombosis, seen in COVID-19.

In summary, there seem to be numerous molecular/cellular pathways potentially explaining the high risk of thrombosis in COVID-19. In this review, we classified some of these pathways under two main categories; dysregulated RAAS and dysregulated immune response. However, it is important to emphasize that pathophysiologic mechanisms of COVID-19 induced thrombosis are often intermingled with multiple crosstalks between pathways during clinical progression of the disease. Future studies will reveal whether one or more of these pathways can be exploited as therapeutic targets to improve thrombotic status in patients with COVID-19.

4. Clinical aspects of COVID-19 induced coagulopathy

Clinically, evidence of inflammation and coagulopathy is commonly observed in patients infected with SARS-CoV2. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-8, are elevated in patients with COVID-19. Rapidly elevating D-dimer levels and elevated fibrinogen degradation products are observed, especially in non- survivors [8]. Also, patients with D-Dimer levels of more than 6 times the upper limit of normal experienced higher mortality in a recent study of almost 500 Chinese patients with COVID-19 [76]. These patients may also have evidence of antiphospholipid antibodies, prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), as well as mild prolongation of the prothrombin time (PT) [77].

Up to 70% of the most severely ill patients with SARS-CoV2 have features of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [78,79]. Unlike sepsis-associated DIC, patients with COVID-19 associated DIC have relatively mild thrombocytopenia (100 × 109/L to 150 × 109/L) and would usually not meet classic ISTH criteria for DIC [79]. In addition, the levels of IL-6 seen in patients with severe COVID-19 are more than five times higher than those observed in bacterial sepsis [80]. Thrombotic microangiopathy, particularly in the lungs, has also been observed [79]. Renal and neurological dysfunction associated with SARS-CoV2 infection has also been postulated to be caused by microvascular thrombotic injury [79]. Finally, as discussed above, there is evidence for direct endothelial damage by the virus with cytokine production, release of cytoplasmic vWF, tissue-type plasminogen activator and urokinase plasminogen activator. Plasmin activation may partially explain the syndrome resulting elevated D-Dimer levels [79,81].

Despite administration of anticoagulant prophylaxis, reported rates of VTE are high - 25% to 69% in critically ill patients in the ICU with COVID-19 and 7% in general medical floor patients [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. The reported incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE) varies from 2.8% to as high as 21% to 23% [8,9,12]. A prospective cohort study of 12 consecutive autopsies performed in COVID-19 deaths revealed bilateral DVT in 7 of 12 with 4 of those patients also demonstrating massive PE as the cause of death [1]. A second autopsy study of 11 randomly selected patients reported segmental and/or subsegmental thrombosis of the pulmonary arteries in all patients despite 10 of the 11 receiving VTE prophylaxis [82]. Thrombosis was not the originally suspected cause of death in any of the patients. Asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT) was reported to be as high as 85% in critically ill patients and 46% of hospitalized medical patients who underwent ultrasound screening [11]. The high rate of VTE, especially PE, is consistent with what has been observed in critically ill patients with severe acute respiratory or pneumonia associated with other respiratory viruses such as H1N1 [10,83]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 86 studies reporting VTE risk in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 reported a VTE prevalence of 7.9% in non-ICU patients and 22.7% in ICU patients with a PE prevalence of 3.5% and 13.7%, respectively [84]. However, at the time of this writing, no data are available on the incidence of VTE in non-hospitalized patients with less severe COVID-19 disease.

While the data on VTE are quite robust, evidence is evolving on the risk of arterial thromboembolism with COVID-19 infection. The frequency of acute ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction appears to be much smaller than the risk of VTE, although not inconsequential [85,86]. At this time, there are no guidelines supporting the use of aspirin for prophylaxis of arterial thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19 [87] although studies with antiplatelets are planned or ongoing (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04365309).

5. Pharmacologic rationale for heparins in treating COVID-19

In addition to its anticoagulant properties, heparins have a long-established history of anti-inflammatory activity. Heparins have demonstrated reductions in IL-6 and IL-8, as well as a reduction in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell damage secondary to lipopolysaccharide induced nuclear factor κB signaling involved in sepsis [81]. Heparin inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis, eosinophil migration, blockade of extracellular histones, and one of the early key steps in sepsis, adhesion of leukocytes to endothelium [88].

There is emerging evidence of heparin's role in reducing infectivity of SARS-COV2. Compared to SARS-CoV1, SARS-CoV2 demonstrates potential binding domains with glycosoaminoglycans, like heparan sulfate located on the surface of almost all mammalian cells, in addition to ACE2. Being a sulfated polysaccharide, heparin has high binding affinity to the spike protein (S-protein) of SARS-CoV2 in vitro. Therefore, heparins have the potential to serve as a decoy to prevent the virus from binding to heparan sulfate co-receptors in host tissues [89]. Recently both unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) have been found to bind to and destabilize the receptor binding domain of SARS-Cov2 spike protein and directly inhibit spike protein binding to the ACE2 receptor at therapeutic concentrations [90]. Because heparins have poor oral bioavailability [91], UFH is being investigated both as a nebulized treatment in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 and as a prophylactic intranasal spray (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04490239 & NCT04397510).

6. Venous thromboembolism risk assessment in hospitalized patients with COVID-19

Numerous governmental and professional associations have published guidance for screening, prevention and treatment of VTE in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (Table 1 [92], [93], [94], [95]). Typically, patients hospitalized with medical illness would be risk-stratified using tools like the PADUA or IMPROVE risk assessment model, and those estimated at higher risk for VTE and low risk for bleeding would receive prophylaxis with standard dose subcutaneous UFH or LMWH according to published guidelines. Because observational studies have shown high risk for VTE in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, most of the available guidelines suggest that all patients who are not at high risk for bleeding, receive an anticoagulant for VTE prophylaxis. Routine screening for lower extremity VTE with Doppler ultrasound, is not recommended. Clinicians should use a low threshold such as worsening oxygenation and rapidly rising D-Dimer, for ordering an appropriate available diagnostic study and initiate therapeutic anticoagulation, however, if PE suspected.

Table 1.

Summary of Published Guidance on Prophylaxis and Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with COVID-19

| Guidance | NIH https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/adjunctive-therapy/antithrombotic-therapy/ | ASH https://www.hematology.org/covid-19/covid-19-and-vte-anticoagulation | AC Forum [92] | Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group [93] | ISTH [94] | CHEST [95] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis in Hospitalized Patients: | ||||||

| Recommend routine screening of asymptomatic patients using bedside Doppler US | No recommendation | No recommendation | No recommendation | Cannot be recommended at this time | Recommend against routine screening | Recommend against routine screening |

| D-Dimer recommended in asymptomatic (for VTE) patients | Yes but data lacking to guide management decisions | No | Yes but use to determine anticoagulation prophylaxis intensification has not been proven | Yes, but for prophylaxis risk stratification only | Yes, but for prophylaxis risk stratification only | Recommend against using D-dimer to guide intensity of anticoagulation |

| VTE Prophylaxis: | ||||||

| VTE risk stratification to determine if prophylaxis is indicated? | No, VTE prophylaxis indicated for all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 | No, VTE prophylaxis indicated for all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 | No, prophylaxis indicated in all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 | Yes | No, VTE prophylaxis indicated for all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 | No, prophylaxis indicated for all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 |

| LMWH recommended over UFH (or DOAC) in hospitalized patients | No | Yes | No, Recommend following existing societal guideline for medical and surgical prophylaxis | No, consider benefits and risks of each class | No | Yes |

| Recommended agents | LMWH or UFH | Prophylactic dose LMWH (hold if platelet counts are less than 25 × 109/L, or fibrinogen less than 0.5 g/L) Fondaparinux if history of HIT Encourage participation in clinical trials of therapeutic anticoagulation Abnormal baseline PT or aPTT is not a contraindication to anticoagulant | For non-critically ill hospitalized patients recommend standard dose prophylaxis anticoagulation For critically ill patients recommend increased doses of VTE prophylaxis (e.g. enoxaparin 40 mg subcut twice daily, enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg subcut twice daily, UFH 7500 units subcut three times daily | For non-hospitalized patients, recommend increased mobility; can consider anticoagulant prophylaxis for those with limited mobility, history of prior VTE or active malignancy No specific agents recommended over others in hospitalized patients | Enoxaparin 40-60 mg subcut daily Enoxaparin 0.5 mg twice daily or IV UFH targeted to anti-factor Xa level 0.30-0.70 (for very high risk including elevated D-Dimer) Obese patients considered for 50% increased dose (BMI > 30kg/m2) UFH for CrCl < 30 mL/min | Recommend against DOACs Recommend against antiplatelet agents In hospitalized patients recommend LMWH or fondaparinux In critically ill hospitalized patients recommend LMWH over UFH or fondaparinux Standard dose prophylaxis recommended over intermediate or full intensity dosing |

| Nonpharmacologic VTE prophylaxis | No recommendation | IPC if anticoagulation contraindicated Combination of IPC plus anticoagulation generally not recommended | IPC if anticoagulation contraindicated Reasonable to employ prophylaxis anticoagulant plus IPC in critically ill patients | ` | Can consider IPC plus anticoagulant for high-risk patients | Recommend IPC for patient with contraindication to anticoagulant prophylaxis Recommend against the addition of IPC to anticoagulant prophylaxis in critically ill |

| Therapeutic intensity anticoagulation an option in very high risk patients? | No data for or against, recommend participation in clinical trials | No, participation in clinical trials preferred | Yes | Insufficient data at this time to consider routine therapeutic or intermediate-dose prophylaxis UFH or LMWH | Yes | No, recommend against |

| Consider extended duration VTE prophylaxis? | Routine use not recommended Rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 31 to 39 days is approved by the FDA for high-risk patients without COVID-19 | Yes | Reasonable to consider on a case-by-case basis for patients who are at low bleed risk and were previously admitted to ICU, intubated and sedated/paralyzed for multiple days or who have ongoing VTE risk factors at the time of hospital discharge (e.g. decreased mobility) Recommend rivaroxaban 31-39 days or enoxaparin 6-14 days | In hospitalized patients: reasonable to consider individualized risk stratification (e.g. reduced mobility, prior VTE, active cancer, D-dimer > 2 times the upper limit of normal) for extended prophylaxis for up to 45 days LMWH or DOACs preferred | Yes, consider for all patients meeting high VTE risk criteria Duration 14-30 days LMWH or DOAC (rivaroxaban) | No, recommend inpatient only |

| VTE Treatment | ||||||

| Recommended agents | Manage as per standard of care for patients without COVID-19 | LMWH or UFH preferred in hospitalized patients Follow ASH 2018 Treatment Guidelines Check for DOAC drug interactions: https://covid19-druginteractions.org/ | LMWH over UFH (use of DOACs not addressed) Recommend against adjusting LMWH dose with anti-Xa levels Recommend UFH over LMWH for CrCl < 15-30 mL/min Check for DOAC drug interactions: https://covid19-druginteractions.org/ | LMWH or UFH for hospitalized patients LMWH or DOAC for patients ready for hospital discharge | LMWH preferred in hospitalized patients and DOAC post-hospital discharge | Initial parenteral anticoagulation with LMWH over UFH and DOACs If no drug interactions, initial apixaban or rivaroxaban can be used After initial parenteral anticoagulation, dabigatran, edoxaban or VKA (with overlap) can be used If outpatient diagnosis, DOAC (initial apixaban or rivaroxaban or initial LMWH followed by dabigatran or edoxaban or VKA plus parenteral overlap) In patients with recurrent VTE despite adherent to oral anticoagulation, recommend switch to LMWH |

| Minimum duration of VTE treatment | Manage as per standard of care for patients without COVID-19 | 3 months Follow ASH 2018 Treatment Guidelines | 3 months | No recommendation | 3 months | 3 months |

ASH, American Society of Hematology; BMI, body mass index; CrCl, creatinine clearance; DOAC, direct acting oral anticoagulant; ICU, intensive care unit; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; subcut, subcutaneously; UFH, unfractionated heparin; US, ultrasound; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Guidelines from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Anticoagulation Forum (AC Forum), International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH), and Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group, suggest that an elevated D-dimer may be used to stratify which patients could potentially receive higher than standard dose anticoagulant prophylaxis but acknowledge that data are lacking [92], [93], [94]. However, the CHEST guidelines specifically state that a D-dimer not to be used to guide the intensity of anticoagulation [95].

7. Clinical trials of heparins for prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism

Heparins have proven effective for both prophylaxis and treatment of VTE in patients hospitalized with acute illness. Because of the high risk of thromboembolic complications and heparin's unique pharmacology demonstrating a reduction in both inflammation and coagulation markers in COVID-19, heparins are being studied for additional clinical endpoints of reduction in hospitalizations, progression to non-invasive mechanical ventilation, as well as mortality. Some, but not all, recently reported retrospective cohort studies, suggest an in-hospital mortality benefit for both UFH and LMWH administered at both prophylaxis and therapeutic treatment doses, especially in patients with more severe COVID-19 as evidenced by elevated D-dimer or need for mechanical ventilation [76,[96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103]] (Summarized in Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Retrospective cohort studies reporting the effect of heparin on all-cause mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

| Country / Author | N | Patients | Heparin | Time from Admission to Administration | Duration of Anticoagulation Treatment | Mortality | Bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA /Paranjpe I et al. [96] | 2773 total 395 mechanically ventilated | Hospitalized COVID-19 | 28% therapeutic treatment dose anticoagulation (TAC) Type, LMWH versus UFH, not specified Control: No treatment or prophylaxis dose anticoagulant | Median 2 days | Median 3 days | Total in-hospital mortality: TAC: 22.5%, median survival 21 days No TAC: 22.8%, median survival 14 days Longer duration of AC associated with reduction in mortality: adjusted Cox proportional HR 0.86 per day (95% CI 0.82-0.89) p<0.001 Mechanically ventilated subgroup in-hospital mortality: AC: 29.1%, median survival 21 days No AC: 62.7%, median survival 9 days | Major bleeding: AC 3% versus No AC 1.9% (p=0.2) |

| China / Tang et al. [76] | Total: 449 consecutive patients with COVID-19 Severe COVID-19 SIC Score ≥ 4: 97 (21.6%) | Hospitalized COVID-19 7 days or longer | UFH or LMWH for 7 days or longer (N=99, 22%) Enoxaparin 40-60 mg subcut daily N=94 UFH 10,000 to 15000 units per day N=4 Control: N=350 without heparin treatment or treated for < 7 days | NA | NA | 28-day mortality Total: heparin 30.3% versus no heparin 29.7%, p=0.910 Subgroup SIC score ≥ 4: 40% heparin versus 64.2% no heparin, p<0.029 Subgroup SIC score < 4: 29% heparin versus 22%, p<0.419 D-Dimer > 3.0 µg/mL (6 fold ULN): 32.8% versus 52.4%, p=0.017 Multivariate predictors of 28-day mortality in severe COVID-19: Treating with heparin OR (95% CI) 1.647 (0.929-2.2921), p=0.088 (Other significant predictors were older age, lower platelet count and higher D-dimer) | NA |

| Spain / Ayerbe L et al. [97] | 2075 | Hospitalized COVID-19 | Any heparin administered at any time during hospitalization (N=1734) versus no heparin (N=285) | NA | NA | Any heparin in-hospital mortality 242 (13.96%) versus no heparin 44 (15.44%) Age- and gender-adjusted any heparin in-hospital mortality versus no heparin OR (95% CI) 0.55 (0.37-9.82), p< 0.001 | NA |

| USA/Nadkarni GN et al. [98] | 4389 | Hospitalized COVID-19 | Any heparin administered ≥ 48 hrs versus not treated (including any treatment < 48 hrs); Therapeutic (N=900), Prophylactic (N=1959), None (N=1530) | NA | NA | Therapeutic anticoagulation in-hospital mortality 28.6% Prophylactic heparin in-hospital mortality 21.6% No anticoagulation in-hospital mortality 25.6% Compared to no anticoagulation, therapeutic AC associated with a 47% reduction in the adjusted hazard of in-hospital mortality (aHR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.45 to 0.62; p < 0.001) Compared to no anticoagulation, prophylactic anticoagulation associated with a 50% lower adjusted hazard of mortality (aHR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.45 to 0.57; p < 0.001) compared with no AC. Lower rates of intubation with both therapeutic and prophylactic anticoagulation compared to no anticoagulation | On-treatment bleeding: Therapeutic anticoagulation 3%, Prophylactic anticoagulation 1.7%, No anticoagulation 1.9% |

| USA/Ionescu F et al. [101] | 127 (75 ICU) Patients who expired from COVID-19 complications | Hospitalized COVID-19 | Therapeutic anticoagulation (N=67) No therapeutic anticoagulation (N=60) Therapeutic anticoagulation with UFH 87% (adjusted by aPTT) or enoxaparin 3% (either 1.5 mg/kg subcutaneous once daily or 1 mg/kg twice daily (or adjusted to 1 mg/kg once daily for CrCl) or oral therapeutic anticoagulation with warfarin (3%), apixaban or rivaroxaban (combined 7%) Prophylactic anticoagulation (N=47) (37%) with subcutaneous UFH 5000 units either twice daily or three times daily or enoxaparin either 30 mg or 40 mg subcutaneous once daily No anticoagulation (N=13) (10%) | Therapeutic anticoagulation initiated median day 6 | Hospital protocol defined duration of anticoagulation as 5 days unless a clear indication or treating clinician choses to continue Median duration of therapeutic anticoagulation 5 days | Median time to death all patients = 9 days Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model: Therapeutic anticoagulation (HR=0.15; 95% CI 0.07-0.32) and prophylactic anticoagulation (HR=0.29; 95% CI 0.15-0.58) independent predictors of longer time to death Later initiation of therapeutic anticoagulation day 3 and beyond provided greater benefit compared to earlier initiation (days 1-2) No interaction between therapeutic anticoagulation and D-dimer | Any bleeding: Therapeutic anticoagulation 19% versus No therapeutic anticoagulation 19% (p=0.877) ISTH Major Bleeding: Therapeutic anticoagulation 3% versus 8% (p=0.18) |

| Italy/Desai A et al. | 575 | Admitted to the emergency department and diagnosed with COVID-19 | LMWH initiated in the emergency department (N=240, 42.6%) type and dose not specified | NA | NA | Multivariate logistic regression: use of LMWH in the emergency department was associated with 60% reduction in mortality (OR 0.4; 95% CI 0.2-0.6) | NA |

| Italy/Albani | 1403 | Hospitalized with COVID-19 | Enoxaparin at some time during hospitalization N=799 (57%) versus no enoxaparin N=604 (43%) Therapeutic enoxaparin (dose > 40 mg) N=312) Prophylactic dose enoxaparin (dose ≤ 40 mg) N=487 Median dose 40 mg [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80] | First dose administered median day 1 | Median duration 6 days | Propensity score -weighted multivariate Cox proportional hazards model: Enoxaparin was associated with a 47% reduction in in-hospital mortality (OR 0.53; 95% CI 0.40-0.70) Sensitivity analysis: Therapeutic enoxaparin OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.38-0.76), Prophylactic dose enoxaparin OR 0.50 (95% CI 0.36-0.69) Enoxaparin associated with reduced risk of ICU admission (OR 0.48; 95% CI 0.32-0.48) but increased length of hospital stay (OR 1.45; 95% CI 1.36-1.54) | NA |

| USA/Ionescu F et al. [99] | 3480 (18.5% ICU) | Hospitalized COVID-19 | Prophylactic anticoagulation N=2121 (60.9%) (subcutaneous enoxaparin either 30mg or 40 mg subcutaneous once daily, fondaparinux 2.5 mg subcutaneous once daily or UFH 5000 units subcutaneous twice or three times a day Therapeutic anticoagulation ≥ 3 days N=998 (28.7%) (Either UFH infusion with at least one therapeutic aPTT, enoxaparin either 1.5 mg/kg subcutaneous once daily, 1 mg/kg subcutaneous twice daily or adjusted by CrCl to 1 mg/kg subcutaneous once daily for CrCl) No anticoagulation N=361 (10.4%) | NA | NA | Propensity score -weighted multivariate Cox proportional hazards model: Compared to those not receiving anticoagulation, prophylactic anticoagulation was associated with a 65% decrease in risk of in-hospital mortality (HR 0.35; 95% CI 0.22-0.54) and therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with an 86% reduction in risk of in-hospital mortality (HR 0.14;95% CI 0.08-0.23) | Major bleeding (either transfusion of 5 or more units of packed red blood cells within 48 hours regardless of hemoglobin level or hemoglobin < 7 g/dL and any red blood cell transfusions or a diagnosis code for major bleeding during hospitalization) Therapeutic anticoagulation 8.1% versus 2.3% prophylactic anticoagulation versus 5.5% no anticoagulation (p<0.001) ICH: Therapeutic anticoagulation 1.3% versus prophylactic anticoagulation 0.5% versus no anticoaglation 1.11% (p=0.028) |

| USA/Hsu A et al. [103] | 468 Severe COVID-19 pneumonia N=151) | Hospitalized COVID-19 | Standard prophylaxis (N=377): enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneous once daily or UFH 5000 units subcutaneous twice or three times daily or apixaban 2.5 mg PO twice daily High-intensity prophylaxis (N=16): enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneous twice daily or UFH 7500 units three times a day Therapeutic anticoagulation (N=48): intravenous heparin infusion or enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily, dose-adjusted warfarin (INR 2.0-3.0), apixaban 5 mg PO twice daily or rivaroxaban 20 mg PO daily No prophylaxis (N=27) | NA | NA | 30-day mortality: Standard prophylaxis 15%, High-intensity prophylaxis 6% Therapeutic anticoagulation 40% Multivariable general linear model: High-intensity prophylaxis was associated with a lower 30-day mortality compared to standard dose prophylaxis (adjusted RR 0.26; 95% CI 0.07-0.97), Therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with a higher 30-day mortality compared to standard prophylaxis (adjusted RR 2.66; 95% CI 1.74-4.08) and high-intensity prophylaxis (p<0.001) No anticoagulation was associated with higher 30-day mortality compared to no anticoagulation (adjusted RR 1.99; 95%1.96-3.75) | In patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: no difference in bleeding (p=0.11) |

aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; CrCl, creatinine clearance; HR, hazard ratio; ISTH, International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis; NA, not available.

In the few studies that have reported the frequency of major bleeding, results are mixed with two studies reporting no difference in major bleeding between therapeutic anticoagulation and prophylactic anticoagulation and one study reporting an increased risk of major bleeding [96,98,99,101]. Because the data reported in these studies are limited with some lacking details regarding heparin type, dose, the reason treatment versus prophylaxis dosing was selected, as well as the potential for confounding, randomized prospective trials are needed. As discussed below, many hospital guidelines and practice guidelines have already been modified to include therapeutic anticoagulation options as a result of these early reports.

There are numerous ongoing or planned clinical trials evaluating dosing strategies for UFH and LMWH for preventing complications from COVID-19 (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04400799, NCT04492254, NCT04427098, NCT04408235, NCT04401293, NCT04372589, NCT04505774, NCT04344756, NCT04377997, NCT04373707, NCT04486508, NCT04409834, NCT04394377, NCT04362085, NCT04420299, NCT04512079, NCT04345848, NCT04508023, NCT04498273, NCT04360824, NCT04372589) (summarized in Table 3). Trial endpoints include progression to ventilation, ICU admission, ventilated/ICU days, and major bleeding, in addition to reduction in both symptomatic venous and arterial thrombosis. All-cause mortality is either part of a composite primary endpoint or a secondary endpoint in the larger multicenter studies. Most comparative studies are evaluating either intermediate fixed doses or therapeutic treatment doses of LMWH compared to standard prophylaxis doses in hospitalized patients. While most studies prefer administration of LMWH, UFH is also being permitted in patients with significant renal dysfunction where dosing of LMWH is less well-studied and drug accumulation is a concern. Some are requiring evidence of coagulopathy including elevated D-dimer values at least 2 to 3 times the upper limit of the normal range. Two studies, OVID and ETHIC, are enrolling never hospitalized serologically positive patients and testing whether administration of standard or weight-based prophylaxis dose enoxaparin for 14 to 21 days prevents hospitalization (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04400799, NCT04492254). There are additional ongoing single center studies not included in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Ongoing multicenter prospective clinical trials evaluating heparins in adults with COVID-19.

| Heparin | Patients | Study Design | Primary Endpoint | Study Acronym / ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enoxaparin 40 mg subcut daily for 14 days versus no treatment | Ambulatory, never hospitalized COVID-19 | Randomized, controlled, open-label | 30-day hospitalizations, 30-day all-cause mortality | OVID / NCT04400799 |

| Enoxaparin 40 mg subcut daily < 100 kg or 40 mg subcut twice daily if ≥ 100 kg for 21 days versus no treatment | Ambulatory symptomatic never hospitalized COVID-19 age ≥ 55 years with at least two of the following additional risk factors: age ≥ 70 years body mass index > 25 kg/m2, COPD, DM, CVD or corticosteroid use | Open-label randomized, Phase IIIb | Hospital admission at 21, 51 and 90 days for ICU, ECMO or Mechanical ventilation | ETHIC / NCT04492254 |

| Observational cohort: enoxaparin 40 mg subcut daily for 14 days Prospective cohort: enoxaparin 60 subcutaneous daily 45 to 60 kg or 80 mg subcut daily 61 to 100 kg or 100 mg subcut daily >100 kg for 14 days | Hospitalized moderate- to severe COVID-19 | 2 parts: a phase II single-arm interventional prospective study; observational prospective cohort study including all patients screened for receiving the study drug but not included in the phase II study. | All-cause mortality at 30 and 90 days | NCT04427098 |

| Enoxaparin 40 mg subcut daily versus enoxaparin 70 mg twice daily | Hospitalized, severe COVID-19 with coagulopathy | Randomized, controlled, open-label | Clinical worsening during hospitalization: death or MI or objectively confirmed arterial TE or VTE, or need for CPAP or noninvasive or mechanical ventilation | NCT04408235 |

| Therapeutic dose anticoagulation with either enoxaparin 1mg/kg subcut twice daily for CrCl ≥ 30ml/min or enoxaparin 0.5mg/kg subcut twice daily for CrCl ≥ 15 ml/min and < 30 ml/min versus institutional standard of care prophylaxis with LMWH or UFH | Hospitalized severe COVID-19, randomized within 72 hours of hospitalization, have a need for supplemental oxygen, and either a D- Dimer > 4 x ULN or sepsis-induced coagulopathy (SIC) score of ≥4 | Open-label (pseudoblinding- site PIs blinded), randomized, active control | Composite outcome of arterial TE, VTE, and all-cause mortality at Day 30 ± 2 days. | HEP-COVID/ NCT04401293 |

| Therapeutic dose anticoagulation with LMWH (enoxaparin preferred over other LMWHs; preferred over UFH) or adjusted-dose UFH (target aPTT or anti-Xa) | Hospitalized < 72 hrs COVID-19 | Randomized, open-label | Ordinal endpoint with three possible outcomes based on the worst status of each patient through day 30: no requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or death | ATTACC / NCT04372589 |

| Therapeutic dose anticoagulation (LMWH or UFH at any dose above prophylactic dose) versus prophylactic dose anticoagulation (LMWH or UFH) | Hospitalized < 72 hrs COVID-19 | Open-label, randomized, masked adjudicators | Number of organ support free days (free of Noninvasive or mechanical ventilation or vasopressors) through day 21 ISTH major bleeding | ACTIV-4 Inpatient/ NCT04505774 |

| Therapeutic tinzaparin 175 IU/kg every 24 hours if CrCl ≥ 20 mL/min or UFH (target anti-Xa) if CrCl < 20 mL/min versus prophylaxis standard of care (LMWH or UFH) for 14 days | Hospitalized COVID-19 Group 1: patients not requiring ICU at admission with mild disease to severe pneumopathy according to The Who Criteria of severity of COVID pneumopathy, and with symptom onset before 14 days, with need for oxygen but NIV or high flow Group 2: Respiratory failure and requiring mechanical ventilation, WHO progression scale ≥ 6, no do-not-resuscitate order (DNR order) | Randomized, 2 parallel arms, stratified for disease severity (ventilated or not) | 14-day survival without ventilation (group 1), 28-day ventilator free survival (Group 2) | CORIMMUNO-COAG / NCT04344756 |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation (enoxaparin preferred with UFH for renal insufficiency or morbid obesity) versus standard anticoagulant prophylaxis (enoxaparin preferred) | Hospitalized with COVID-19 and elevated D-Dimer (>1500 mg/L) without severe ARDS | Randomized, open-label | Composite endpoint of death, cardiac arrest, symptomatic VTE, arterial TE, MI, or hemodynamic shock at day 21 | NCT04377997 |

| Standard dose LMWH versus weight-adjusted LMWH (e.g. enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily <50 kg, 50 mg twice daily 50-70 kg, 60 mg twice daily 70-100kg, 70 mg twice daily > 100kg) | Hospitalized COVID-19 | Randomized, open-label controlled, stratified (ICU or not) | Symptomatic VTE at day 28 | COVI-DOSE / NCT04373707 |

| Standard prophylaxis with enoxaparin versus intermediate-dose prophylaxis with enoxaparin (atorvastatin 20 mg versus placebo) | Hospitalized within 7 days to ICU | Randomized, controlled, open-label, 2 × 2 factorial design | Composite of incident VTE, undergoing ECMO, and all-cause mortality at 30 days, composite of objectively-confirmed VTE, undergoing ECMO, or death from any cause | INSPIRATION / NCT04486508[93] |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation with enoxaparin 1 mg/kg subcut twice daily or UFH (aPTT 1.5-2 x control) versus standard prophylaxis (enoxaparin 40 mg subcut daily or UFH 5000 units three times daily) (Clopidogrel 300 mg followed by 75 mg daily versus placebo) | Hospitalized ICU COVID-19 | Randomized, controlled, open-label, 2 × 2 factorial design | VTE at day 28 or hospital discharge whichever sooner Hierarchical composite: death due to VTE, arterial thrombosis, type 1 MI, ischemic stroke, systemic embolism or acute limb ischemia, or clinically silent DVT | COVID PACT / NCT04409834 |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation with either: oral rivaroxaban 20 mg daily (15 mg daily if CrCl 30-49 mL/min and/or concomitant use of azithromycin) or enoxaparin 1 mg/kg every 12 hours or UFH (preferred if DIC) versus usual anticoagulant prophylaxis standard of care for 30 days | Hospitalized COVID-19 with D-dimer > 3 x ULN | Randomized, controlled, open-label | Composite endpoint: mortality, number of days alive, number of days in the hospital and number of days with oxygen therapy at the end of 30 days (win ratio) | ACTION / NCT04394377 |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation (either treatment dose enoxaparin or UFH infusion per weight-based nomogram) administered until discharged or 28 days versus standard of care | Hospitalized COVID-19 with D-dimer > 2 x ULN within 72 hours of admission | Randomized, controlled, open-label | ICU admission, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or all-cause death up to 28 days | NCT04362085 |

| Therapeutic dose bemiparin (115 IU/kg subcut daily) versus prophylaxis dose bemiparin (3500 IU/kg subcut daily) for 10 days | Hospitalized COVID-19 with D-dimer > 500 ng/mL | Randomized, single-blind | Composite endpoint (worsening): death, ICU admission, need for either non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation, progression to moderate / severe respiratory distress syndrome according to objective criteria (Berlin definition), VTE, MI, or stroke | NCT04420299 |

| FREEDOM Trial Prophylaxis enoxaparin (40 mg subcut daily or 30 mg subcut daily for CrCl <30 mL/min) versus Therapeutic dose enoxaparin (1 mg/kg subcut every 12 hours or 1 mg/kg subcut daily for CrCl <30 mL/min) and Therapeutic dose apixaban (5 mg PO every 12 hrs or 2.5 mg every 12 hours for patients with at least two of three of age ≥80 years, weight ≤60 kg or serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL) | Hospitalized COVID-19 but not yet intubated | Randomized, controlled, open-labelled | The time to first event rate within 30 days of randomization of the composite of all-cause mortality, intubation requiring mechanical ventilation, systemic VTE confirmed by imaging or requiring surgical intervention OR ischemic stroke confirmed by imaging Number of in-hospital rate of BARC 3 or 5 bleeding | NCT04512079 |

| COVID-HEP Therapeutic anticoagulation with UFH or enoxaparin versus prophylaxis dose UFH or enoxaparin (augmented prophylaxis dose if in ICU) from admission to end of hospital stay | Hospitalized COVID-19 | Randomized, parallel, open-label, single masked | 30-day composite outcome arterial or venous thrombosis, DIC and all-cause mortality ISTH major bleeding | NCT04345848 |

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg PO daily x 35 days versus placebo | Medically ill outpatients with symptomatic COVID-19 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 35-day composite outcome of symptomatic VTE, MI, ischemic stroke, acute limb ischemia, non-CNS systemic embolization, all-cause hospitalization and all-cause mortality | PREVENT-HD / NCT04508023 |

| Apixaban 2.5 mg PO twice daily versus apixaban 5 mg PO twice daily versus aspirin 81 mg PO daily versus placebo for 45 days | Adults > age 40 and < 80 years found to be COVID-19 positive with elevated D-dimer and hsCRP who do not require hospitalization due to stable COVID-19 related symptoms status. | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 45-day composite endpoint of need for hospitalization for cardiovascular/pulmonary events, symptomatic VTE, MI, ischemic stroke, and all-cause mortality | ACTIV Outpatient / NCT04498273 |

| Standard prophylactic dose enoxaparin (40 mg subcut daily or 30 or 40 mg subcut twice daily if BMI ≥30kg/m2; standard of care arm) versus intermediate-dose enoxaparin (1 mg/kg subcut daily or 0.5 mg/kg subcut twice daily if BMI≥30kg/m2; intervention arm) | Hospitalized with COVID-19 | Randomized, open-label, controlled | 30-day all-cause mortality ISTH major bleeding | NCT04360824 |

| Therapeutic dose UFH or LMWH versus standard prophylaxis according to local standard | Hospitalized with COVID-19 | Randomized, open-label, parallel | 30-day ordinal endpoint with three possible outcomes based on the worst status of each patient through day 30: no requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or death. | ATTACC / NCT04372589 |

aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CrCl, creatinine clearance; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; ISTH, International Thrombosis and Haemostasis; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; MI, myocardial infarction; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; SIC, sepsis induced coagulopathy; subcut, subcutaneous; TE, thromboembolism; UFH, unfractionated heparin; VTE, venous thromboembolism; WHO, World Health Organization.

8. Current practice guideline recommendations for prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19

When selecting an agent for prophylaxis some, but not all guidelines listed in Table 1 recommend LMWH over UFH primarily to decrease the number of injections and risk of healthcare provider exposure. UFH is recommended over LMWH for patients with severe renal insufficiency. A direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) is not recommended for VTE prophylaxis secondary to the potential for drug interactions and longer half-lives which may make hemostasis following surgery or invasive procedures difficult to manage. Most guidelines recommend standard doses of anticoagulant prophylaxis for non-critically ill hospitalized patients with consideration of intermediate doses for obese patients and critically ill patients. Two guidelines, those from the AC Forum and ISTH, give an option for using therapeutic anticoagulation in the highest risk patients [92,94]. Fondaparinux is recommended in patients with a history of or suspected heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. If an anticoagulant is contraindicated, prophylaxis with intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) is recommended. There are mixed recommendations regarding the addition of IPC to anticoagulant prophylaxis for high-risk patients [92,94].

Only one guideline, the Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group, addresses non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19, recommending increased mobility with a consideration for anticoagulant prophylaxis for those with limited mobility, history of VTE or active malignancy [93]. Routine post-hospital discharge prophylaxis is not recommended by the NIH or CHEST [95]. However, the NIH, American Society of Hematology (ASH), AC Forum, Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group and ISTH suggest individualized patient decision making based on continued VTE risk, such as those who were hospitalized in the ICU [92,93]. When indicated, the guidelines recommend either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for a duration of 14 to 45 days post-discharge.

For treatment of VTE in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 most of guidelines suggest parenteral anticoagulation with switch to a DOAC (assuming no drug interactions) as the patient transitions to the outpatient setting [92], [93], [94]. When using UFH in therapeutic doses, the guidelines suggest monitoring anti-Xa levels rather than an aPTT as prolonged aPTT with elevated levels of factor VIII and positive lupus anticoagulants is common [104].

9. Examples of institutional protocols

Given the data reporting a higher incidence of VTE in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, especially with severe disease being treated in the ICU and a lack of randomized controlled trials evaluating intermediate- and therapeutic treatment LMWH and UFH, several health systems have updated their institutional recommendations to recommend higher dosing. For example, Brigham and Women's Hospital recommends standard treatment with enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneous daily (UFH 5000 units subcutaneous three times daily for CrCl < 30 mL/min) for VTE prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients with CrCl ≥30 mL/min weighing less than 120 kg. For patients in ICU and post-ICU, higher doses for these patients are recommended – enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneous twice daily (UFH 7500 units subcutaneous three times daily) (https://covidprotocols.herokuapp.com/pdf/Covid-19%20Drugs&Treatment%20Guide%20092020.1.pdf). In contrast, Yale New Haven Health System recommends prophylaxis stratified by D-Dimer with standard prophylaxis doses (plus low-dose aspirin 81 mg/day unless contraindicated) for patients with COVID-19 and a D-Dimer less than 5 mg/L and intermediate dose prophylaxis anticoagulation (enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg subcutaneous twice daily) for patients with either D-dimer ≥5 mg/L or receiving convalescent plasma (in addition to aspirin 81 mg/day) (https://medicine.yale.edu/intmed/COVID-19%20TREATMENT%20ADULT_10.27.2020_398806_5_v1.pdf). Neither recommend therapeutic anticoagulation in patients without documented VTE. In contrast, the Eastern Virginia Medical School Medical Group Critical Care COVID-19 Management Protocol recommends therapeutic anticoagulation with enoxaparin 1 mg/kg subcutaneous twice daily for patients with CrCl ≥ 30 mL/min, 1 mg/kg subcutaneous once daily for CrCl 15-29 mL/min and UFH for patients with CrCl < 15 mL/min (https://www.evms.edu/media/evms_public/departments/internal_medicine/EVMS_Critical_Care_COVID-19_Protocol.pdf). In the Brigham and Women's Hospital institutional guidelines, standard treatment dose enoxaparin is recommended for initial treatment of VTE while in the Yale New Haven Health System guidelines either standard dose enoxaparin or a DOAC are recommended.

10. Conclusion and perspectives

COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically increased the risk of venous and arterial thromboembolic events in many patients. Indeed, the link between COVID-19 and coagulopathy is attracting attention from both clinicians and basic scientists. At the molecular/cellular levels, numerous signaling pathways due to dysregulated RAAS may contribute to the observed coagulopathy in COVID-19. On the other hand, excessive innate immune response to SARS-CoV2 for which there is no prior acquired immunity mediates various pathways that may lead to thrombosis. These pathways may offer new opportunities for the development of innovative therapies to treat COVID-19 induced coagulopathy. Currently clinicians are facing challenges with selecting the most effective prophylactic anticoagulant strategies. Future research is moving forward to identify pathophysiologic mechanisms, biomarkers and appropriate anticoagulation dosing strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Currently we recommend that clinicians enroll patients in clinical trials where available. Because data are lacking on the safety of therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation and current guidelines give options, an individualized approach is recommended balancing benefit versus bleeding risk. Studies evaluating the role of anticoagulation in all phases of care of patients with COVID-19 are underway including out-of-hospital ambulatory, hospitalized, and post-hospital patients. Results of these ongoing studies will help shape our future practice.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ali-Spinler-Ethical statement

We the undersigned declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published before and is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

We confirm that all authors are responsible for the content and have read and approved the manuscript; and that the manuscript conforms to the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals published in Annals in Internal Medicine

We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process. He/she is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs.

Signed by all authors as follows:

Mohammad A.M Ali

Sarah A. Spinler

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2020.12.004.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Wichmann D, Sperhake JP, Lutgehetmann M, Steurer S, Edler C, Heinemann A, et al. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-2003. May 6 PMCID. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu X, Chang XN, Pan HX, Su H, Huang B, Yang M, et al. Pathological changes of the spleen in ten patients with coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) by postmortem needle autopsy. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49(6):576–582. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200401-00278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. PMCID: PMC7192101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanff TC, Mohareb AM, Giri J, Cohen JB, Chirinos JA. Thrombosis in COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:1578–1589. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juthani P, Bhojwani R, Gupta N. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) manifestation as acute myocardial infarction in a young, healthy male. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8864985. PMCID: PMC7364231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. e60PMCID: PMC7207073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFadyen JD, Stevens H, Peter K. The emerging threat of (micro)thrombosis in COVID-19 and its therapeutic implications. Circ Res. 2020;127(4):571–587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317447. PMCID: PMC7386875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M, Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T, et al. Humanitas COVID-19 Task Force. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. PMCID: PMC7177070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llitjos JF, Leclerc M, Chochois C, Monsallier JM, Ramakers M, Auvray M, Merouani K. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1743–1746. doi: 10.1111/jth.14869. PMCID: PMC7264774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. PMCID: PMC7262324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren B, Yan F, Deng Z, Zhang S, Xiao L, Wu M, Cai L. Extremely high incidence of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis in 48 patients with severe COVID-19 in Wuhan. Circulation. 2020;142(2):181–183. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, Parmentier E, Duburcq T, Lassalle F, et al. and Lille ICU Haemostasis COVID-19 Group. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142(2):184–186. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helms J, Severac F, Merdji H, Angles-Cano E, Meziani F. Prothrombotic phenotype in COVID-19 severe patients. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06082-7. PMCID: PMC7237619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh B, Aly R, Kaur P, Gupta S, Vasudev R, Virk HS, et al. COVID-19 infection and arterial thrombosis: report of three cases. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.08.115. PMCID: PMC7462876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choudry FA, Hamshere SM, Rathod KS, Akhtar MM, Archbold RA, Guttmann OP, et al. High thrombus burden in patients with COVID-19 presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(10):1168–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. PMCID: PMC7149362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. PMCID: PMC7097841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakob A, Schachinger E, Klau S, Lehner A, Ulrich S, Stiller B, Zieger B. Von willebrand factor parameters as potential biomarkers for disease activity and coronary artery lesion in patients with Kawasaki disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179(3):377–384. doi: 10.1007/s00431-019-03513-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L, et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15562-9. 1620-020-15562-9. PMCID: PMC7100515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou YJ, Okuda K, Edwards CE, Martinez DR, Asakura T, Dinnon KH, 3rd, et al. SARS-CoV-2 reverse genetics reveals a variable infection gradient in the respiratory tract. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.042. PMCID: PMC7250779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li MY, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang XS. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1) doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00662-x. 45-020-00662-x. PMCID: PMC7186534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res. 2000;87(5) doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.e1. E1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner AJ, Hiscox JA, Hooper NM. ACE2: from vasopeptidase to SARS virus receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(6):291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.04.001. PMCID: PMC7119032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verdecchia P, Cavallini C, Spanevello A, Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. PMCID: PMC7167588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581(7807):221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fried JA, Ramasubbu K, Bhatt R, Topkara VK, Clerkin KJ, Horn E, et al. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;141(23):1930–1936. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Regulation of ACE2 in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(6) doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00426.2008. H2373-9. PMCID: PMC2614534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vuille-dit-Bille RN, Camargo SM, Emmenegger L, Sasse T, Kummer E, Jando J, et al. Human intestine luminal ACE2 and amino acid transporter expression increased by ACE-inhibitors. Amino Acids. 2015;47(4):693–705. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1889-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopes RD, Macedo AVS, de Barros E Silva PGM, Moll-Bernardes RJ, Feldman A. D'Andrea Saba Arruda G, et al. and BRACE CORONA investigators. Continuing versus suspending angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: impact on adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)–the BRACE CORONA trial. Am Heart J. 2020;226:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.05.002. PMCID: PMC7219415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia X, Al Rifai M, Hussain A, Martin S, Agarwala A, Virani SS. Highlights from studies in cardiovascular disease prevention presented at the digital 2020 European society of cardiology congress: prevention is alive and well. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020;22(12) doi: 10.1007/s11883-020-00895-z. 72-020-00895-z. PMCID: PMC7532123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;7:819–824. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaughan DE, Lazos SA, Tong K. Angiotensin II regulates the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in cultured endothelial cells. A potential link between the renin-angiotensin system and thrombosis. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(3):995–1001. doi: 10.1172/JCI117809. PMCID: PMC441432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levi M, van der Poll T. Inflammation and coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2 Suppl):S26–S34. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c98d21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danilczyk U, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme II in the heart and the kidney. Circ Res. 2006;98(4):463–471. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205761.22353.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: Physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(1):C82–C97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos RAS, Sampaio WO, Alzamora AC, Motta-Santos D, Alenina N, Bader M, MJ Campagnole-Santos. Vol. 98. 2018. The ACE2/Angiotensin-(1-7)/MAS axis of the renin-angiotensin system: Focus on angiotensin-(1-7) pp. 505–553. (Physiol Rev). PMCID: PMC7203574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. PMCID: PMC7172722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hemila H, Chalker E. Vol. 52. 2020. Vitamin C as a possible therapy for COVID-19; pp. 222–223. (Infect Chemother). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe T, Barker TA, Berk BC. Angiotensin II and the endothelium: Diverse signals and effects. Hypertension. 2005;45(2):163–169. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153321.13792.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yau JW, Teoh H, Verma S. Endothelial cell control of thrombosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12872-015-0124-z. 130-015-0124-z. PMCID: PMC4617895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu S, Xu X, Kang Y, Xiao Y, Liu H. Degradation and detoxification of azo dyes with recombinant ligninolytic enzymes from aspergillus sp. with secretory overexpression in pichia pastoris. R Soc Open Sci. 2020;7(9) doi: 10.1098/rsos.200688. PMCID: PMC7540776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin J, Collot-Teixeira S, McGregor L, McGregor JL. The dialogue between endothelial cells and monocytes/macrophages in vascular syndromes. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(17):1751–1759. doi: 10.2174/138161207780831248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leebeek FW, Eikenboom JC. Von willebrand's disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(21):2067–2080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1601561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanhoutte PM, Shimokawa H, Feletou M, Tang EH. Endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease - a 30th anniversary update. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2017;219(1):22–96. doi: 10.1111/apha.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Do H, Healey JF, Waller EK, Lollar P. Expression of factor VIII by murine liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(28):19587–19592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fahs SA, Hille MT, Shi Q, Weiler H, Montgomery RR. A conditional knockout mouse model reveals endothelial cells as the principal and possibly exclusive source of plasma factor VIII. Blood. 2014;123(24):3706–3713. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-555151. PMCID: PMC4055921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Everett LA, Cleuren AC, Khoriaty RN, Ginsburg D. Murine coagulation factor VIII is synthesized in endothelial cells. Blood. 2014;123(24):3697–3705. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554501. PMCID: PMC4055920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. m1091. PMCID: PMC7190011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]