Abstract

Migrant and refugee pregnant women constitute a highly vulnerable group to mental disorders. The rates of mental illness of migrants and refugees are higher than those of host populations, with migrant women being more likely to suffer from prenatal depression. A Policy Paper was developed based on a literature review conducted in Medline, Scopus and Google Scholar. Filtering criteria were: year of publication (2002–2017), study topic relevance, and English language. A total of 63 documents were identified. Most of the documents were scientific papers while a large number of documents were reports of EU committees and networks on migrant issues or annual reports of international bodies. From the analysis of existing evidence, four major topics emerged for the perinatal health of migrant women: 1) Prevalence and risk factors for antenatal mental disorders, 2) Assessment of mental disorders, 3) Healthcare professionals’ training on supporting migrant and refugee pregnant women, and 4) Interventions for the mental health of migrant women. Midwives and other members of interdisciplinary teams have to be trained and culturally competent to successfully meet the needs of migrant and refugee pregnant women.

Keywords: mental disorders, pregnant, well-being, healthcare professionals, refugee, migrant

COMMENTARY

The number of international migrants worldwide reached 244 million in 2015, and the total number of refugees was estimated at 19.5 million in 20141. These population groups face higher rates of physical and mental illness than the respective host populations2. Female migrants comprise 48 per cent of all international migrants1, with migrant and refugee pregnant women forming a highly vulnerable group to mental disorders, due to their unique needs during this period3.

Although perinatal mental health is recognized as a significant public health issue4, its complexity and diversity make it difficult to understand or manage3. Women have an increased risk of mental illness during the perinatal period, with implications to themselves, their infants, families, and society. Especially during the antenatal period, mental disorders constitute a common complication of pregnancy5.

Only by understanding how migration is related to mental illness can we establish how it might be detected and treated and what interventions should be developed and implemented to combat it successfully. With the above in mind, the purpose of this synthesis is to summarise the available data concerning mental health status among migrant and refugee pregnant women and the role of healthcare professionals in addressing this issue.

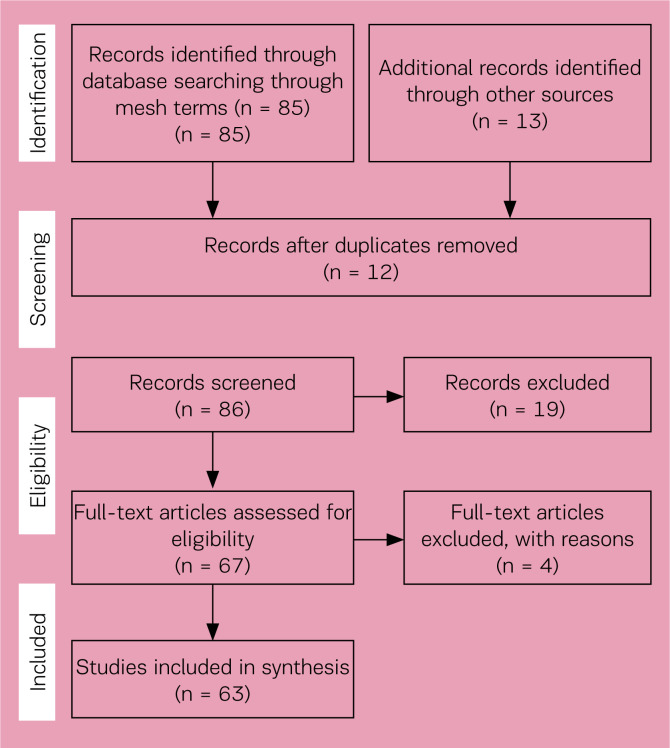

A literature review was conducted in Medline, Scopus and Google Scholar, using the combinations of the following mesh terms: ‘mental health’, ‘perinatal’, ‘immigrant/migrant pregnant’, ‘refugee pregnant’, ‘healthcare professionals’, and ‘interventions’. The search was conducted in the keywords, abstracts and titles of articles, between July and August 2017. Inclusion criteria included: the year of publication (2002–2017), study topic relevance, and English language. In addition to the above, snowball searches were performed in the websites of national and international professional colleges and associations as well as institutes and organizations in the field of health [e.g. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE); American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); Canadian Medical Association (CMA); Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG); World Health Organization (WHO)]. Two reviewers initially screened the titles and abstracts of all the articles for relevance to the review topic. The articles that underwent the screening phase were read in full and analysed for the key message. The documents located through the electronic search were organised based on the type of document they represented. The analysis followed the principles of content analysis.

Even though this review is not a systematic review, a flow diagram of the search selection for the included studies according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement6 is presented in Figure 1. A total of 63 documents were identified and met the inclusion criteria, focusing on the perinatal health of migrant, refugee and asylum-seeking women. Documents included scientific papers and grey literature including reports of EU committees and networks on migrant issues or annual reports of international bodies.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram

From the analysis of existing evidence, four major topics emerged for the perinatal health of migrant women: 1. Prevalence and risk factors for antenatal mental disorders, 2. Assessment of mental disorders, 3. Healthcare professionals’ training on supporting migrant and refugee pregnant women, and 4. Interventions for the mental health of migrant women.

1. Prevalence and risk factors for antenatal mental disorders

Mental disorders are encountered more frequently in women than in men7. Common perinatal mental disorders have a higher prevalence in low- and middle-income countries, particularly among poorer women with genderbased risks or a psychiatric history8. The percentage of women that experience a mental disorder is about 10% worldwide8. Although current evidence suggests that the rates for depression have no differences in perinatal and non-perinatal populations, the rates for anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder may be slightly higher in the perinatal population9.

Depression is one of the most common complications during pregnancy, with a higher incidence of major depressive disorder episodes (MDD) and depression onset during the childbearing years10,11. The prevalence of MDD, specified by diagnostic criteria during pregnancy is 12.7%, while 37% of women report experiencing depressive symptoms while being pregnant. The prevalence of depression is 8.5–12.9% in high-income countries12-15, though in low- and middleincome countries rates are increased to 15.6–25.8%15-17. The most significant predictors for antenatal depression are low self-esteem, antenatal anxiety, low social support, negative cognitive style, major life events, low income and history of abuse18. Although anxiety is known to have a higher prevalence than depression at all stages of pregnancy, there is a high level of comorbidity between them at approximately 60%10,11,19. When a mother experiences depression, anxiety, or stress during pregnancy, she may expose both herself and her infant to multiple psychological risks11,20, including impaired bonding with the fetus and the newborn, increased risk of poor psychological postnatal adjustment, postnatal depression11,21, and physiological consequences, including low birth weight22,23, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth22-26 and also consequences that involve family relations and wider society27.

As far as it concerns socioeconomic determinants about mental health for these adverse outcomes, the correlation becomes even stronger when it comes to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and generally among lower socioeconomic groups28. According to evidence, the rates of mental illness of migrants and refugees are higher than those of host populations3,4,29 with one in three migrant women being affected by depression15 and being more likely to suffer from prenatal depression30.

As migrant women are more likely to be poorer financially, and most global migration is from LMICs, we may expect worse adverse child outcomes associated with perinatal mental disorders among migrant women31. Besides, being a pregnant migrant woman can be a source of cultural and psychological distress, which can, further, lead to the immediate or delayed manifestation of mental health disorders, either in them or their offspring32.

Risk factors for depression in migrant pregnant women identified in the recent systematic review by Anderson et al.31 are lack of social support, marital strain/lack of marital support, time in host country, socioeconomic difficulty (including lack of money for basic needs and housing difficulties), stress/mental health, low acculturation level, not working or attending school in pregnancy and precarious legal status.

Due to cultural and linguistic barriers, migrants may be unwilling or feel unable to seek help, and those who are eager to do so are often not aware of the services available to them. These women present commonly with somatic symptoms and are left in social isolation. In general, they tend to prefer practical help instead of pharmacological interventions33.

Migrant pregnant women who experience single-parenthood or psychological difficulties, which may be associated with social or psychological vulnerability, require special attention, as they are disproportionately likely to use psychoactive substances like alcohol and tobacco, and these put them and their children at high risk of poor health outcomes34. Migrant pregnant women with a low acculturation level are less often smokers and women with a high level are more often smokers than native women35. In studies from the United Kingdom, Sweden, the United States, and Turkey, it was found that smoking increases with increasing acculturation35-38. Prevention measures have to prevent women with a low acculturation level from starting to smoke and induce those with a high acculturation level to quit. Smoking and acculturation are group phenomena. Smoking, in interpersonal level, is influenced by peer group social norms, by the tobacco control policies in each country and by the social support systems. Also, acculturation is a dynamic process depending on interactions between immigrants and natives39. Hence, it is vital to engage migrant communities in the prevention process35. The qualitative study of Fellmeth et al.29 showed that mental illness was recognised as a concept by the majority of participants, who were migrant and refugee pregnant women. Moreover, mental illness was thought to be more prevalent during and following pregnancy owing to lack of family support and concerns about the future29.

Moreover, when it comes to asylum seekers, the risk of violence during pregnancy is associated with a higher risk of prenatal depressive symptoms40 and it is less likely to be reported41. A first step in preventing mental health problems is to recognise violence as a clinically relevant and identifiable risk factor for antenatal depression, significant or minor, in migrant women. Healthcare providers who care for pregnant women can be trained to identify and to appropriately direct women and their families to the available services30.

Also, the stress associated with the legal processes around asylum-seeking procedures and the fear of an unsuccessful claim and subsequent deportation can further damage the pregnant woman’s mental and physical health42. The asylum-seeking procedure itself and the accompanying poverty and deprivation together with the possible emotional impact and cultural ramifications, if, for example, the woman is pregnant as a result of rape, can lead to these women experiencing psychological issues including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder43.

Establishing the prevalence of depression in pregnant and post-partum migrants and refugees is essential for the development of appropriate mental health services29. Although there is an increasingly hostile environment towards migrants, society must be involved to confront discrimination, poverty and social isolation that migrant women suffer31.

2. Assessment of mental disorders

The establishment of routine screening for abuse in the maternity services settings, as well as tested, proper, culturally sensitive referral systems are needed30. Clinicians need to be aware of psychosocial issues in this vulnerable population and be able to conduct careful screening and follow-up33. According to NICE44, midwives should provide information when booking the appointment for women with a previous severe mental health problem (severe and incapacitating depression, psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder or postpartum psychosis) or any current mental health problem; information should be about how their mental health problem and its treatment might affect them or their baby. Women who cannot communicate in English should be provided with equal access to information with the help of interpreters, supported by cultural mediators if possible, or other appropriate local support available, as provided by independent advocates in the United Kingdom, when needed.

Also, general practitioners (GPs), midwives, health visitors and obstetricians should ask all women about their emotional state at each routine antenatal contact to support identification and discussion of mental health problems. In light of the above, possible identification questions (Table 1) that could be asked by healthcare professionals when booking the woman’s appointment and routine visits in pregnancy, focusing on her mental health and well-being have been recommended by NICE45.

Table 1.

Depression identification questions

| During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless? |

| During the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things? |

| Questions on anxiety using the 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2) |

| Over the last 2 weeks, have you been feeling nervous, anxious or on edge? |

| Over the last 2 weeks, have you not been able to stop or control worrying? |

NICE. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. Clinical guideline [CG192]. London: National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2014.

Routine depression screening at antenatal care visits (in each trimester of pregnancy)46,47, as well as information on immigration indicators (duration of residence in the host country, language fluency, legal status as a proxy indicator of socioeconomic condition and difficulties, religion and ethnicity) and psychosocial risk factors (living conditions, social and marital support), are crucial and should be considered an essential part of routine perinatal health data collection48,49, especially when providing care to refugee women49. It is important that women are interviewed privately, to avoid the possibility of self-censorship. This requires the availability of cultural mediators as well as competent interpreters and healthcare professionals50,51. Moreover, in primary care settings, pregnant migrant women should be provided with descriptive materials, in their mother tongue, regarding depressive disorder, receive translated screening questions and have access to trained interpreters, ideally supported by cultural mediators, to facilitate the diagnostic interview, and systematic inquiries about losses, stressors and symptoms42-51.

Also, GPs and mental health professionals should carry out comprehensive mental health assessments for women who may have a mental health problem in pregnancy to aid diagnosis and identify the need for extra support. Especially for women with diverse cultural backgrounds, NICE45 recommends that ‘healthcare professionals should be culturally competent in their discussions with them in order to support full discussion and comprehensive mental health assessment and women should have access to an interpreter, supported, if possible, by a cultural mediator or […] independent advocate as in the case of UK, if needed’. Furthermore, when a woman is referred to mental health professionals, she should be assessed within two weeks of referral and start treatment within six weeks of referral. These assessments and interventions should be culturally designed to be understood and communicated effectively.

3. Healthcare professionals’ training in supporting migrant and refugee pregnant women

With regard to mental healthcare provision in migrant and refugee pregnant women, there are various barriers to healthcare systems, as free care can be extremely limited in some cases. However, this specific review mainly focuses on the healthcare professional’s important role and needs52.

Asylum seeking pregnant women may not always have positive experiences of maternity care, and midwives and other professionals may not be able to meet their special needs53-56. NICE45 suggests that healthcare professionals should be given training on: the specific health needs of women who are recent migrants, asylum seekers or refugees; the specific social, religious and psychological needs of women in these groups; the most recent government policies on access and entitlement to care for them. Also, healthcare professionals should offer the woman information on access and entitlement to healthcare, discuss with the woman the importance of having her hardcopy maternity record with her at all times at the booking appointment, and avoid making assumptions based on the woman’s culture, ethnic origin or religious beliefs. Besides, healthcare professionals should provide the woman, who does not speak or read English, with access to an interpreter (who may be a link worker or advocate as in the case of UK and should not be a member of the woman’s family, her legal guardian or her partner)44. Moreover, health care professionals should communicate with the woman in her preferred language, and when giving spoken information, they should ask the woman about her understanding of what she has been told to ensure she has understood it correctly44. It is crucial to improve the training of perinatal healthcare professionals to encourage the development of maternity-linked transcultural sensitivity and competence. Additionally, recent work conducted in a capacity-building project focusing on refugee health (EUropean Refugees-HUman Movement and Advisory, EUR-HUMAN Project, http://eur-human.uoc.gr) reports that compassion is a critical competency for healthcare professionals treating refugees and migrants, and highlights the fact that linguistic and cultural barriers exacerbate the lack of compassion in care, especially where healthcare information and psychological support are necessary and where appropriate supporting frameworks are missing.

Moreover, as the next generation of midwives, pre-registration students also require adequate preparation in order to adequately care for asylum-seeking women57. ‘The pregnant woman within the global context’ model for midwifery education can be used in midwifery education to prepare students in caring for pregnant women seeking asylum. This model was designed to facilitate midwives to visualise the woman as the centre of her care. It incorporates broader factors, on a global level, which could impact on the health and social care needs of a pregnant woman in the process of seeking asylum. It also prompts students to consider the influence of existing narratives and dominant discourses on perceptions of asylum-seeking and is designed to encourage students to question such discourses. It has been designed as a tool to assist midwifery students in assessing the health and social-care needs of pregnant women seeking asylum57.

4. Interventions for the mental health of migrant women

Among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, the need for early identification of pregnant women with mental disorders and provision of early interventions and prevention research is highly punctuated58. Improving communication and allowing migrant women to preserve some of their traditions may increase their mental wellbeing59. Peer support groups reduce social isolation and feelings of desperation due to immigration and family separation. This could be an effective way of preventing postpartum depression among migrant women60. Moreover, the availability of childcare facilities, transportation and support from family members and spouses can facilitate seeking help. Group meetings can be an effective way to provide social support and health-promotion information47. Besides, mind-body interventions might alleviate women’s anxiety during pregnancy61 and physical exercise may be an effective way to treat depression symptoms during pregnancy62. Guidance from NICE4 states that health professionals should consider exercising treatment for antenatal depression, and the RCOG63,64 and the ACOG65 have stated that exercise can provide mental health benefits during pregnancy. Also, group programs that incorporate education about mental and physical health, available support, and socialization, appear to be efficient in engaging and assisting migrant perinatal women. According to evidence, these are best delivered by clinicians from similar cultural backgrounds33. It is further suggested that more formal and systematic training, including the development of assessment tools in the local languages, would enable better identification and treatment of mental illness in this population29.

Moreover, a feasible way of overcoming the treatment barriers of perinatal mental health disorders and making sure that women obtain the care they need is by integrating perinatal mental health services into primary care. Perinatal mental health is central to the values and principles of Midwifery, and the establishment of community midwifery services for perinatal mental health is inexpensive and quite beneficial. Community midwives can effectively assess, recognise, support and refer women with perinatal mental disorders and thus provide holistic women care66.

This discussion piece is not intended to be exhaustive and developed as a systematic review. However, it offers a glimpse into the current literature. A systematic review on the topic would paint a fuller picture of current trends in terms of access, availability and quality of perinatal health care for migrant women, a gap that should be addressed in future research.

CONCLUSIONS

Assessment of the prevalence of and risk factors for antenatal mental disorders in migrant and refugee pregnant women is most important for managing healthcare services. There is also a profound need for healthcare professionals to be able to assess the risk factors of antenatal depression in all migrant and refugee pregnant women. Perinatal healthcare professionals should be encouraged to be culturally sensitive and to achieve cultural competency, including training in modalities such as compassion, so as to facilitate access to healthcare services and to better help women to cope with them, develop trusting relationships allowing them to reveal their depressive symptoms and to ensure acceptance of and compliance with their treatment. Mental health-related interventions such as peer support groups, group meetings, mind-body interventions, and physical exercise can improve mental health status. Mostly, integration of mental health services into primary care settings appears to be the most efficient and effective manner to facilitate the early assessment and timely treatment of perinatal mental disorders, with community midwifery playing a central role in achieving better mental health outcomes for the women and their offspring.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

VG Vivilaki reports that she is the Editor-in-chief of EJM journal. VG Vivilaki, M Iliadou, M Papadakaki, E Sioti, P Giaxi, E Leontitsi, A Mastroyiannakis report grants from Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency, during the conduct of the study. The rest of the authors also have completed and submitted an ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and none was reported.

FUNDING

This paper reports on work performed in the context of a European Project funded in the context of the 3rd Health Programme (2014–2020) by the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency, with Project number 738148 and entitled Operational Refugee And Migrant Maternal Approach (ORAMMA).

PROVENANCE AND PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.DESA . International Migration Report 2015: Highlights. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Hossain M. Migration and health: a framework for 21st-century policy-making. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):e1001034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins CH, Zimmerman C, Howard LM. Refugee, asylum seeker, immigrant women and postnatal depression: rates and risk factors. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NICE . NICE guideline for antenatal and postnatal mental health. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanley J. A guide for health professionals and support workers. Stoodleigh, Devon ,UK: Florence Production Ltd; 2015. Listening visits in perinatal mental health. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(2):139–49H. doi: 10.2471/blt.11.091850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BC Reproductive . BC Reproductive Mental Health Program. 2014. Mental Health Program. & Perinatal Services BC. Best practice guidelines for mental health disorders in the perinatal period. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee AM, Lam SK, Sze Mun Lau SM, Chong CS, Chui HW, Fong DY. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):1102–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000287065.59491.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard M, Wittkowski A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women Birth. 2015;28(3):179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis C-L, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014;384:1775–1788. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:805–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fellmeth G, Fazel M, Plugge E. Migration and perinatal mental health in women from low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017;124(5):742–752. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surkan PJ, Kennedy CE, Hurley KM, Black MM. Maternal depression and early childhood growth in developing countries: systematic review and metaanalysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011;89:607–615. doi: 10.2471/blt.11.088187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Araya R, Williams MA. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Oct 1;3(10):973–982. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30284-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000116689.75396.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1012–24. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katon W, Russo J, Gavin A. Predictors of postpartum depression. Journal of women's health. 2014;23(9):753–759. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cross-Sudworth F. Racism and discrimination in maternity services. British Journal of Midwifery. 2007;15(6):327–31. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2007.15.6.23670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding M, Leach M, Bradley H. The effectiveness and safety of ginger for pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic review. Women Birth. 2013;26(1):e26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mancuso RA, Schetter CD, Rini CM, Roesch SC, Hobel CJ. Maternal prenatal anxiety and corticotropinreleasing hormone associated with timing of delivery. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(5):762–769. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138284.70670.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li D, Liu L, Odouli R. Presence of depressive symptoms during early pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(1):146–153. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibanez G, Charles MA, Forhan A, et al. Depression and anxiety in women during pregnancy and neonatal outcome: data from the EDEN mother-child cohort. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88(8):643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO-UNFPA . Maternal mental health and child health and development in low and middle income countries. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. The Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1800–1819. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fellmeth G, Plugge E, Paw MK, Charunwatthana P, Nosten F, McGready R. Pregnant migrant and refugee women's perceptions of mental illness on the Thai-Myanmar border: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:93. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0517-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miszkurka M, Zunzunegui MV, Goulet L. Immigrant status, antenatal depressive symptoms, and frequency and source of violence: what’s the relationship? Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2012;15(5):387–396. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson FM, Hatch SL, Comacchio C, Howard LM. Prevalence and risk of mental disorders in the perinatal period among migrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(3):449–462. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0723-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhugra D. Migration, distress and cultural identity. Br Med Bull. 2004;69:129–141. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neale A, Wand A. Issues in the evaluation and treatment of anxiety and depression in migrant women in the perinatal period. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):379–382. doi: 10.1177/1039856213486215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melchior M, Chollet A, Glangeaud-Freudenthal N, et al. Tobacco and alcohol use in pregnancy in France: the role of migrant status: the nationally representative ELFE study. Addict Behav. 2015;51:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiss K, Breckenkamp J, Borde T, Brenne S, David M, Razum O. Smoking during pregnancy among Turkish immigrants in Germany—are there associations with acculturation? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;17(6):643–652. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzgerald EM. Evidence-based tobacco cessation strategies with pregnant Latina women. Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hawkins SS, Lamb K, Cole TJ, Law C. Millennium Cohort Study Child Health Group. Influence of moving to the UK on maternal health behaviours: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:1052–1055. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39532.688877.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urquia ML, Janevic T, Hjern A. Smoking during pregnancy among immigrants to Sweden,1992-2008: the effects of secular trends and time since migration. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:122–127. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reiss K, Lehnhardt J, Razum O. Factors associated with smoking in immigrants from non-western to western countries–what role does acculturation play? A systematic review. Tobacco induced diseases. 2015;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s12971-015-0036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart DE, Gagnon AJ, Merry LA, Dennis CL. Risk factors and health profiles of recent migrant women who experienced violence associated with pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(10):1100–1106. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kingston D, Heaman M, Urquia M, et al. Correlates of Abuse Around the Time of Pregnancy: Results from a National Survey of Canadian Women. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(4):778–789. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds B, White J. Seeking asylum and motherhood: health and wellbeing needs. Community Practitioner. 2010;830(20):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burnett A, Fassil Y. Meeting the Health Needs of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK: An Information and Resource Pack for Health Workers. London: National Health Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44.NICE . Pregnant women with complex social factors: a model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors: Clinical Guideline [CG110] London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.NICE . Clinical guideline [CG192] London: National Institute of Health and Care Excellence; 2014. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ACOG . ACOG Committee Opinion No. 343: psychosocial risk factors: perinatal screening and intervention. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.CMA . Best Practice Guidelines for Mental Helath Disorders in the Perinatal Period. Canadian Medical Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gagnon AJ, Zimbeck M, Zeitlin J. Migration and perinatal health surveillance: an international Delphi survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;149(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gagnon AJ, Wahoush O, Dougherty G, et al. The childbearing health and related service needs of newcomers (CHARSNN) study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2006;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bashiri N, Spielvogel AM. Postpartum depression: a cross-cultural perspective - confinement and convalescence of Chinese women after childbirth. Primary Care Update for Ob/Gyns. 1999;6(3):82–87. doi: 10.1016/s1068-607x(99)00003-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels H, Rashid M, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E824–925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mental health promotion and mental health care in refugees and migrants. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 53.McLeish J. Mothers in Exile: Maternity experiences of asylum seekers in England. London: Maternity Alliance; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLeish J. Maternity experiences of asylum seekers in England. British Journal of Midwifery. 2005;13(12):782–785. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2005.13.12.20125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaudion A, Allotey P. Maternity Care for Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Hillingdon: A Needs Assessment. Brunel University: Uxbridge, Centre for Public Health Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waugh M. The Mothers in Exile Project. Women Asylum Seekers' and Refugees' Experiences of Pregnancy and Childbirth in Leeds Womens Health Matters. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haith-Cooper M, Bradshaw G. Meeting the health and social care needs of pregnant asylum seekers; midwifery students' perspectives: part 3; ‘the pregnant woman within the global context’; an inclusive model for midwifery education to address the needs of asylum seeking women in the UK. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(9):1045–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. The Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1800–1819. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fassaert T, De Wit MA, Tuinebreijer WC, et al. Acculturation and psychological distress among non- Western Muslim migrants- a population-based survey. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(2):132–143. doi: 10.1177/0020764009103647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gardner PL, Bunton P, Edge D, Wittkowski A. The experience of postnatal depression in West African mothers living in the United Kingdom: a qualitative study. Midwifery. 2014;30(6):756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marc I, Toureche N, Ernst E, et al. Mind-body interventions during pregnancy for preventing or treating women's anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. journal;2011(7):CD007559. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007559.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daley AJ, Foster L, Long G, et al. The effectiveness of exercise for the prevention and treatment of antenatal depression: systematic review with meta-analysis. BJOG. 2015;122(1):57–62. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.RCOG . Good Practice Guide Number 14. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2011. Management of women with mental health issues during pregnancy and the postnatal period. [Google Scholar]

- 64.RCOG . Statement No.4. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2015. Exercise in Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Artal R, O'Toole M. Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(1):6–12. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vivilaki V, Haros D, Iliadou M. Integrating perinatal mental health into primary health: the role of community midwife. International Journal Of Occupational Health and Public Health Nursing. 2016;3(2) [Google Scholar]