Abstract

Immobilization of enzyme on metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) has drawn increasing interest owing to their many well-recognized characteristics. However, the pore sizes of MOFs (mostly micropores and mesopores) limit their application for enzyme immobilization to a great extent owing to the large size of enzyme molecules. Synthesis of MOFs with macropores would therefore solve this problem, typically encountered with conventional MOFs. In this work, macroporous zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIF-8), referred to as M-ZIF-8, were synthesized and used for immobilization of Aspergillus niger lipase (ANL). Immobilization efficiency using M-ZIF-8 and enzymatic catalytic performance for biodiesel preparation were investigated. The immobilized ANL on M-ZIF-8 (ANL@M-ZIF-8) showed higher enzymatic activity (6.5-fold), activity recovery (3.8-fold), thermal stability (1.4- and 3.4-fold at 80 and 100 °C, respectively), reusability (after five cycles, 68% of initial activity was maintained), and porosity than ANL on conventional ZIF-8 (ANL/ZIF-8). In addition, by using ANL@M-ZIF-8 for catalyzing a biodiesel production reaction, a higher fatty acid methyl ester yield was achieved.

1. Introduction

In recent years, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have attracted increasing research interest due to their well-recognized characteristics, such as versatile structural tailorability and diversity, extremely high surface area, and high crystallinity.1−3 Therefore, widespread application of MOFs has recently been witnessed, especially in gas sorption and separation, sensors, and catalysis. However, these favorable characteristics of MOFS present great potential of their use in enzyme immobilization. Indeed, enzyme immobilization on MOFs has been regarded as the new promising direction in enzyme technology. Many enzyme/MOF composites have been developed and showed better stability and catalytic performance than other conventional immobilized enzymes.4−10 Enzymes such as peroxidase and trypsin have been immobilized with MOFs as the carrier in many cases, while relatively few studies related to lipase immobilized with MOs were reported.11−15

Lipase has found applications in many important fields, including catalyzing renewable oils for biodiesel production. Successful immobilization of this important enzyme on metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) promises to further promote its application. Typically, the immobilization strategies of enzymes on MOFs include surface immobilization, pore adsorption (i.e., diffusion into the pores of MOFs), and encapsulation (such as through coprecipitation and cocrystallization) within the MOFs.16−21 Among them, surface immobilization has been the most commonly used because synthesized MOFs generally possess micropores or small mesopores (less than 4 nm), which prevents lipase diffusion.16,17 Therefore, the high porosity of MOFs is not fully utilized, leading to poor enzyme immobilization efficiency.13,16 Besides that, surface immobilization is susceptible to leaching, resulting in low stability. Reports on lipase immobilization in the mesopores of MOFs are scarce in literature. Nevertheless, these limited reports have shown promising results. For example, as compared with the free Bacillus subtilis lipase, 17 times higher enzymatic activity was achieved in the lipolytic esterification of small molecules, like lauric acid, with benzyl alcohol, when B. subtilis lipase was immobilized in the mesopores of a hierarchically porous Cu-BTC, with an average mesopore size of about 34 nm. After 10 cycles, the immobilized BSL2 still exhibits 90.7% of its initial enzymatic activity and 99.6% of its initial conversion.15

Co-encapsulation immobilization has also suggested to overcome the enzyme diffusion problem, encountered with post immobilization in MOFs with microspores. The co-encapsulations allowed caging the large enzyme molecules within the matrix during curation, which results in enhanced stability. However, this may not be useful for use in reactions involving large molecules, as in the case of biodiesel production from oils. Recently, Shen et al.22 reported in science a new strategy to synthesize MOFs with macropores. With their proposed strategy, they were able to construct highly oriented and ordered macropores within a single crystal of MOF. This breakthrough paved the way for synthesizing three-dimensionally ordered macro-microporous materials in a single-crystalline form.

Synthesizing MOFs with larger pores (mesopore/macropore) has been explored in this work to allow high loading of the enzyme. The potential of using the developed macroporous MOF for lipase’s immobilization is assessed by investigating the immobilization efficiency and catalytic performance of the immobilized lipase in biodiesel production. Highly ordered and oriented macroporous ZIF-8 were synthesized by the hard template method22 using assembled polystyrene (PS) nanosphere monoliths as a template. Aspergillus niger lipase (ANL) was immobilized on the prepared macroporous ZIF-8 by direct diffusion into the macropores. The performance of the immobilized ANL on the macropore ZIF-8 (ANL@ZIF-8) was compared to that of surface immobilized ANL on the widely used stable ZIF-8 (ANL/ZIF-8) that contains only micropores in the order of 1 nm. Specific enzymatic activity, activity recovery, thermal stability, and biodiesel production were compared using ANL@M-ZIF-8 and ANL/ZIF-8.

2. Materials, Methods, and Experimental Sections

2.1. Materials

Free lipase from genetically modified A. niger, with a specific enzyme activity of 5.45 U/mg (45 °C, hydrolysis enzyme activity, substrate is tributyl glyceride, enzyme activity is defined as the amount of enzyme required to catalyze the hydrolysis of a substrate to produce 1 μmol fatty acid per minute), was a kind gift from Novozymes (Denmark). A bicinchroninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit was purchased from Beijing Leagene Biotech Co. Ltd., China. Tributyrin was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry, Japan. Heptadecanoic acid methyl ester was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and ethanol and methanol were purchased from Beijing Chemical Works Co. Ltd., China. Soybean oil was bought from the local market. All the other chemicals were obtained commercially and of analytical grade.

2.2. Characterization Methods

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with a Cu Kα anode (λ = 0.15406 nm) at 40 kV and 40 mA. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured at 77 K on a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 analyzer. The samples were degassed at 80 °C for 12 h before the measurements. Specific surface areas were calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method in the relative pressure range P/P0 = 0.05–0.30. Field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) pictures were taken using a JEOL JSM 7401F, at an acceleration voltage of 5.0 kV. The fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) production was measured using an Agilent 7890 gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a CP-FFAP capillary column (0.32 mm × 0.30 μm × 25 m). The initial column temperature was 180 °C, maintained for 0.5 min, then heated to 250 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, and held for 6 min. A detector and injector were set at 250 and 245 °C, respectively.

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.3.1. Preparation of a 3D Ordered PS Template

A 3D ordered PS template was prepared using the same method described by Shen et al.22 with modification. The purchased styrene was thoroughly washed with 10 wt % NaOH solution and deionized water to remove the stabilizer. Then, 65 mL of the washed styrene was mixed with 500 mL of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K-30) aqueous solution (5 mg/mL) in a 1 L triple-neck round-bottom flask. The mixture was bubbled with nitrogen for 15 min and then heated at 75 °C using an oil bath for 30 min under mechanical stirring (450 rpm). After that, 50 mL aqueous solution of K2S2O8 (20 mg/mL) was added quickly to the flask and the stirring speed was increased to 450 rpm. After leaving the mixture to react for 24 h at 75 °C and 450 rpm, it was cooled down and the produced template was collected by vacuum filtration through two qualitative filter papers. After filtering for around 24 h, the formed filter cake was washed by deionized water and ethanol and then dried overnight in an oven at 60 °C.

2.3.2. Synthesis of Single-Crystalline Ordered Macroporous ZIF-8 (M-ZIF-8)

M-ZIF-8 was prepared according to the method described by Shen et al.22 with modification. The ZIF precursor solution in methanol was prepared by adding 8.15 g of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O and 6.75 g of 2-methylimidazole to 45 mL of methanol. The collected filter cake from Section 2.3.1 was soaked in the precursor–methanol solution for 1 h, then degassed in vacuum for 10 min to fill all interstitial spaces between 3D colloidal spheres with precursor solution, and dried at 50 °C for 12 h. The collected filter cake was then soaked in CH3OH/NH3·H2O (1:1 v/v) solution at room temperature (RT). This mixture was degassed in vacuum for 10 min and then left to react at RT and atmospheric pressure for 24 h. The filter cake, which gradually broke into small pieces due to the growing stress of ZIF-8, was filtrated and dried in air. The confined PS templates inside M-ZIF-8 were removed by soaking in tetrahydrofuran for 24 h. To ensure a thorough etching of the PS, this process was repeated over five times. Finally, the obtained white powder was vacuum-dried at 100 °C overnight.

2.3.3. Synthesis of Microporous ZIF-8

Conventional microporous ZIF-8 was prepared according to the method described by Wu et al.23 with modification. Zn (NO3)2·6H2O (1.68 g, 5.65 mmol) and 2-methylimidazole (3.70 g, 45 mmol) were separately dissolved in 80 mL of methanol. The two solutions were rapidly mixed in a glass beaker (250 mL); then, a white powdery solid was obtained after magnetic stirring for 24 h at room temperature. The solid product was centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 5 min) and washed with methanol several times. Finally, the white ZIF-8 powder was dried in a vacuum-drying oven overnight at 100 °C.

2.3.4. Immobilization of A. niger Lipase (ANL)

To immobilize ANL inside M-ZIF-8 and the conventional ZIF-8, 60 mg of ZIF-8 or M-ZIF-8 was added to 800 μL of deionized in a 2 mL plastic centrifuge tube. After ZIF was uniformly dispersed by ultrasonication, 200 μL of soluble ANL was added, and the mixture was maintained at 45 °C and 200 rpm for over 4 h in a thermostatic shaker. The immobilized lipase in ZIF was then collected by centrifugation followed by vacuum filtration while washing once with water. Finally, the immobilized lipase was freeze-dried using lyophilizer. The loading was calculated from the difference in the protein concentration (measured using a BCA protein assay kit) in the original solution and what is left in the supernatant, as given by eq 1

| 1 |

where C0 and C1 are the protein concentrations of the supernatant before and after immobilization (mg/mL), respectively, V is the volume of total solution (1 mL), and ms is the weight of added ZIF (60 mg).

2.3.5. Enzyme Activity Assay

The specific activity of the free and immobilized lipase was measured by a butyrin hydrolysis method according to a previous report.24 All data presented are average results of triplicated repetition of each run.

The calculation of specific activity and activity recovery is as follows:

where V1 is the titrate value of free or immobilized lipase (mL), V0 is the titrate value of the blank (mL), CNaOH is the concentration of sodium hydroxide (0.05 M), mt is the mass of free or immobilized lipase (mg), t is the reaction time duration, Uhetero represents the specific enzymatic activity of immobilized lipase (μmol·min–1·mg–1), Ufree represents the specific enzymatic activity of free lipase (μmol·min–1·mg–1), L is the loading amount, ms is the weight of support, and ωf is the mass fraction of free enzyme in its solution.

2.3.6. Lipase-Catalyzed Methanolysis of Soybean Oil

Enzymatic methanolysis of soybean oil was conducted in a 50 mL Erlenmeyer flask, which was placed in a thermostatic shaker at 45 °C and 200 rpm. The reaction conditions were as follows: 10 g of soybean oil, 1 g of water, 120 U per gram soybean immobilized lipase of equal enzymatic activity (corresponding 0.1 and 0.7 g for M-ZIF-8 and ZIF-8, respectively), and four stepwise equal addition (at 0, 2, 4, and 6 h) of 460 μL of methanol, summing to a total methanol/oil molar ratio of 4:1. At different intervals, 50 μL of sample was withdrawn from the reaction mixture and sent for GC analysis. The sample was first treated using a speed vacuum concentrator at 85 °C, 2000 rpm, and −0.1 MPa. Then, a weighed sample of 10 μL was added to 600 μL of heptadecanoic acid methyl ester ethanol solution (internal standard, 0.8 g/L), and 1 μL of the resultant mixture was injected in the GC. The FAME yield was calculated using eq 2

| 2 |

where mi and ms are the masses of the internal standard and sample, respectively, and Ai and As are the GC peak areas of the internal standard and FAMEs, respectively.

2.3.7. Reusability Test of ANL@M-ZIF-8 in Methanolysis of Soybean Oil

The methanolysis reaction, similar to the one described in Section 2.3.5, was carried out, and 50 μL of the organic phase was withdrawn at 12 h and treated using a speed vacuum concentrator for GC analysis. After that, the reaction mixture was centrifuged at 10000 rpm, and the immobilized enzyme was collected. The recovered enzyme was used in a second batch of the same methanolysis reaction, and the same process was repeated. All presented data are the average values of triplicated runs. The same procedure was used for the reusability test of ANL@ZIF-8.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of M-ZIF-8 for ANL Immobilization

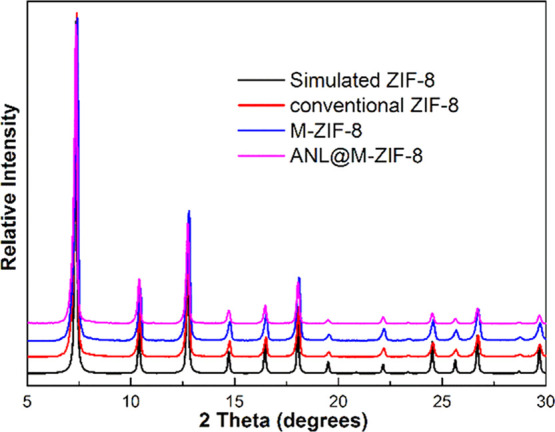

Ordered macro-microporous ZIF-8 was prepared, as described in Section 2.3.2, by assembling the PSs into highly ordered 3D PS monoliths followed by ZIF-8 precursor filling and crystallization. The SEM images of the produced M-ZIF-8 were analyzed, and it was found that the macropore size was about 200 nm. The crystallinity and micropore structure of the produced M-ZIF-8 were also assessed by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD). The PXRD pattern of M-ZIF-8, shown in Figure 1, displays clear characteristic peaks, which indicate that the crystallinity and structure of ZIF-8 were preserved in the prepared M-ZIF-8. Figure 1 also shows that the PXRD pattern did not change with the immobilization of ANL on M-ZIF-8, which also indicates that the crystalline structure maintained well after immobilization.

Figure 1.

PXRD patterns of conventional ZIF-8, M-ZIF-8, and ANL@M-ZIF-8 with simulated ZIF-8 as a comparison.

The shapes of the N2 physisorption isotherms at 77 K of the synthesized M-ZIF-8, shown in Figure 2, were found to be similar to those of the conventional ZIF-8, resulting in a similar BET surface area. This is a further proof of the uniformity of the micropore structure. Analysis of the DFT pore size distribution (Figure 2 inset) further supports that M-ZIF-8 and ZIF-8 possess a similar pore size distribution on a micropore scale.

Figure 2.

N2 sorption isotherms of conventional ZIF-8 and M-ZIF-8 at 77 K. The inset shows the corresponding micropore size distribution from the DFT model.

3.2. Comparative Study of Immobilizing Lipase on ZIF-8 and M-ZIF-8

After the structural confirmation, ZIF-8 and M-ZIF-8 were used to immobilize A. niger lipase (ANL) by physical adsorption. Despite using the same immobilization approach, the results of the two supports were different. The loading efficiencies of the two supports were compared. It was found that ANL@M-ZIF-8 showed a higher specific enzymatic activity and activity recovery as compared to ANL/ZIF-8. The activity recovery of ANL@M-ZIF-8 was 93%, which was 3.8-fold higher than that of ANL@ZIF-8, which was 24%. The enzyme activity showed even higher improvement, with ANL@M-ZIF-8 having an activity of 11 U/mg, which was 6.5-fold higher than that of ANL@ZIF-8, which was only 1.7 U/mg. This improvement was mainly due to the larger and more ordered pores of M-ZIF-8. This allowed ANL molecules to penetrate into the macropores of 200 nm size, resulting in pore adsorption of ANL@M-ZIF-8. With ZIF-8 however, the small micropores prevented the ANL molecules from entering the pores, which results in only surface adsorption of ANL@ZIF-8. The enzyme activity and activity recovery of ANL@M-ZIF-8 were 7-and 10-fold higher than those found in our previous work18 with the same enzyme, ANL, surface immobilized on UiO-66. The enzymatic activity of ANL@M-ZIF-8 was also much higher than that of the corresponding free lipase, which is about 5.45 U/mg.

Thermal stabilities of ANL/ZIF-8 and ANL@M-ZIF-8 were compared by measuring the remaining specific enzymatic activity after heating at different temperatures (in a range of 40–100 °C) for 2 h. As shown in Figure 3, the activity of ANL@M-ZIF-8 was nearly intact for all tested temperature below 90 °C. The relative activity dropped to 87% and 67% at 90 and 100 °C, respectively. On the composite, ANL/ZIF-8 could only maintain its full activity up to 50 °C and continued to gradually decline to 69% and 20% at 80 and 100 °C, respectively. These results indicate that macropore adsorption significantly enhances the thermal stability of immobilized ANL on ZIF-8. This could be due to a temperature gradient that develops within the ZIF pores. This gradient results in subjecting the enzyme immobilized deeper into the macrospores of M-ZIF-8 to temperatures lower than those that the enzyme immobilized on the surface of the ZIF-8 is subjected to.

Figure 3.

Thermal stability of ANL/ZIF-8 and ANL@M-ZIF-8 at different temperatures.

The porosities of M-ZIF-8 and ZIF-8 after ANL immobilization were also studied. As shown in Figure 4, ANL/ZIF-8 lost nearly all the porosity of ZIF-8 owing to the complete blockage of the micropores by the large molecules of ANL, which were immobilized on the surface of ZIF-8. This phenomenon is a common problem encountered with the surface immobilization of enzymes, which was mentioned in previous works.11,13,25,26 Macropore adsorption, suggested in this work, could be a good solution to this problem. As shown from the isotherm of ANL@M-ZIF-8, the porosity of M-ZIF-8 was mostly preserved. The BET surface area of ANL@M-ZIF-8 was determined to be 1276 m2/g, which was 78% of that of empty M-ZIF-8, which was 1636 m2/g.

Figure 4.

N2 sorption isotherms of ANL@M-ZIF-8 (black) and ANL/ZIF-8 (red) at 77 K.

3.3. Comparative Study on ANL@M-ZIF-8 and ANL/ZIF-8 in Biodiesel Production

The catalytic performance of ANL@M-ZIF-8 as a biocatalyst for biodiesel production was investigated and compared to that of ANL/ZIF-8. As shown in Figure 5, at early stages of the reaction (until 12 h), the reaction rate using ANL@M-ZIF-8 was slightly slower than that of ANL/ZIF-8. It should be noted however that these results were obtained using the same enzyme activity. Owing to the higher activity of ANL@M-ZIF-8, the amount used (0.1 g) was lower than that required when ANL/ZIF-8 was used (0.7 g). With the same activity, the lower rate using ANL@M-ZIF-8 can be attributed to the diffusion resistance encountered by substrates, and products, to reach the enzyme molecules adsorbed within the macropores. This diffusion resistance however was much less with the enzyme immobilized on the surface of ANL/ZIF-8. The situation changed at a later stage, after 12 h of reaction, when the substrates diffused deeper into the ANL@M-ZIF-8 structure and more enzyme molecules were utilized. The FAME yield continued to increase reaching 80% at 24 h. Meanwhile, with ANL/ZIF-8, the yield reached a plateau of 65% after 12 h. The main reason for this is the deactivation of the enzyme with methanol and glycerol deposition. Although all the enzyme was readily available for reaction with ANL/ZIF-8, the enzyme utilization of the available enzyme was gradual in the case of ANL@ZIF-8, resulting in the initial faster rate of the former. In the latter however, the outer parts of the enzyme were utilized first, while the inner ones were not used. The enzyme molecules adsorbed deeper into the macropores of M-ZIF-8 were preserved and utilized at a later stage of the reaction, resulting in a continuous increase in the yield after 12 h.

Figure 5.

Catalytic performances of ANL/ZIF-8 and ANL@M-ZIF-8 in biodiesel production at 45 °C, 200 rpm, 10 g of soybean oil, 1 g of water, 120 U per gram soybean immobilized lipase, and four stepwise additions of 460 μL of methanol.

To confirm the explanation above, the two enzymes were reused for five consecutive batches with fresh oil and methanol, as described in Section 2.3.6. As shown in the results in Figure 6, with ANL/ZIF-8, the yield dropped significantly in the second cycle, and the enzyme maintained only 10% of the activity in the first cycle. No product was observed in the following cycles, suggesting that the enzyme was completely deactivated. This was mainly due to the deactivation by excess methanol present in the system. With ANL@M-ZIF-8 however, the enzyme was more stable under the same conditions, maintaining up to 68% of its initial activity after five cycles. The decreased activity of ANL@M-ZIF-8 after five cycles was mainly caused by the accumulated adsorbed glycerol in the macropores. To further validate this, the experiment was repeated with addition of methanol (methanol/oil molar ratio of 2:1) only once while leaving all other reaction conditions the same. By doing so, ANL@M-ZIF-8 retained nearly all its activity in the second use, whereas ANL/ZIF-8 lost 90% of its activity, similar to what happened with the four stepwise additions. By further reducing the addition of methanol (only 1:1 molar ratio of methanol/oil), both enzymes retained their full activity in the second reuse. This clearly indicates that ANL@M-ZIF-8 has a better methanol tolerance than ANL/ZIF-8 owing to the protection of the enzyme within the macropore.

Figure 6.

Reusability of ANL@M-ZIF-8 and ANL/ZIF-8 in biodiesel production at 45 °C and 200 rpm. Each cycle consists of 10 g of fresh soybean oil, 1 g of water, and four stepwise additions of 460 μL of methanol with the collected immobilized lipase from the previous cycle.

4. Conclusions

Lipase was successfully immobilized in the macropores of MOF for the first time to the best of our knowledge. Macropore adsorption was found to significantly improve the enzymatic activity, thermal stability, reusability, and catalytic performance of lipase on ZIF-8. When the immobilized lipase in ZIF-8 of macropores was used for biodiesel production, an enhancement in methanol tolerance was also observed. Most significantly, the specific enzymatic activity of ANL@M-ZIF-8 increased by 6.5-fold, and it was thermally more stable than ANL/ZIF-8. In addition, unlike with ZIF-8, M-ZIF-8 maintained a good porosity after enzyme immobilization. Compared to other immobilized lipases on different MOFs, ANL@M-ZIF-8 showed superior activity, thermal stability, and methanol tolerance. The new enzyme immobilization strategy on ZIF developed in this work would broaden the prospect and applications of immobilized enzymes on MOFs.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the support from Joint Research Program between UAE University and Institutions of Asian Universities Alliance (AUA) (UAEU-AUA Fund number 31R167), China-Latin America Joint Laboratory for Clean Energy and Climate Change (KY201501004), and Dongguan Science & Technology Bureau (Innovative R&D Team Leadership of Dongguan City, 201536000100033).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Furukawa H.; Cordova K. E.; O’Keeffe M.; Yaghi O. M. The Chemistry and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. 10.1126/science.1230444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.-C. J.; Kitagawa S. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5415–5418. 10.1039/C4CS90059F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.; Wen H.-M.; Cui Y.; Zhou W.; Qian G.; Chen B. Emerging Multifunctional Metal–Organic Framework Materials. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 8819–8860. 10.1002/adma.201601133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Lykourinou V.; Vetromile C.; Hoang T.; Ming L.-J.; Larsen R. W.; Ma S. How Can Proteins Enter the Interior of a MOF Investigation of Cytochrome c Translocation into a MOF Consisting of Mesoporous Cages with Microporous Windows. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13188–13191. 10.1021/ja305144x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Y.-H.; Lo S.-H.; Yang N.-S.; Singco B.; Cheng Y.-J.; Wu C.-Y.; Chang I.-H.; Huang H.-Y.; Lin C.-H. Trypsin-Immobilized Metal–Organic Framework as a Biocatalyst In Proteomics Analysis. ChemPlusChem 2012, 77, 982–986. 10.1002/cplu.201200186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D.; Liu T.; Su J.; Bosch M.; Wei Z.; Wan W.; Yuan D.; Chen Y.-P.; Wang X.; Wang K.; Lian X.; Gu Z.-Y.; Park J.; Zou X.; Zhou H.-C. Stable metal-organic frameworks containing single-molecule traps for enzyme encapsulation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5979. 10.1038/ncomms6979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Yang C.; Ge J.; Liu Z. Polydopamine tethered enzyme/metal-organic framework composites with high stability and reusability. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 18883–18886. 10.1039/C5NR05190H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong G.-Y.; Ricco R.; Liang K.; Ludwig J.; Kim J.-O.; Falcaro P.; Kim D.-P. Bioactive MIL-88A Framework Hollow Spheres via Interfacial Reaction In-Droplet Microfluidics for Enzyme and Nanoparticle Encapsulation. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 7903–7909. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b02847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh F.-K.; Wang S.-C.; Yen C.-I.; Wu C.-C.; Dutta S.; Chou L.-Y.; Morabito J. V.; Hu P.; Hsu M.-H.; Wu K. C.-W.; Tsung C.-K. Imparting Functionality to Biocatalysts via Embedding Enzymes into Nanoporous Materials by a de Novo Approach: Size-Selective Sheltering of Catalase in Metal–Organic Framework Microcrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4276–4279. 10.1021/ja513058h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; Moon S.-Y.; Guelta M. A.; Harvey S. P.; Hupp J. T.; Farha O. K. Encapsulation of a Nerve Agent Detoxifying Enzyme by a Mesoporous Zirconium Metal–Organic Framework Engenders Thermal and Long-Term Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8052–8055. 10.1021/jacs.6b03673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S.; Kim Y.; Kim S.-J.; Kwon T.-H.; Huh S.; Park S. Bio-functionalization of metal-organic frameworks by covalent protein conjugation. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 2904–2906. 10.1039/c0cc03288c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo J.; Aguilera-Sigalat J.; El-Hankari S.; Bradshaw D. Magnetic MOF microreactors for recyclable size-selective biocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1938–1943. 10.1039/C4SC03367A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.-L.; Yang N.-S.; Chen Y.-T.; Lirio S.; Wu C.-Y.; Lin C.-H.; Huang H.-Y. Lipase-Supported Metal–Organic Framework Bioreactor Catalyzes Warfarin Synthesis. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 115–119. 10.1002/chem.201405252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samui A.; Chowdhuri A. R.; Mahto T. K.; Sahu S. K. Fabrication of a magnetic nanoparticle embedded NH2-MIL-88B MOF hybrid for highly efficient covalent immobilization of lipase. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 66385–66393. 10.1039/C6RA10885G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y.; Wu Z.; Wang T.; Xiao Y.; Huo Q.; Liu Y. Immobilization of Bacillus subtilis lipase on a Cu-BTC based hierarchically porous metal-organic framework material: a biocatalyst for esterification. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 6998–7003. 10.1039/C6DT00677A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Dai L.; Liu D.; Du W.; Wang Y. Progress & prospect of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for enzyme immobilization (enzyme/MOFs). Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 793–801. 10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Wang X.; Hou M.; Li X.; Wu X.; Ge J. Immobilization on Metal-Organic Framework Engenders High Sensitivity for Enzymatic Electrochemical Detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13831–13836. 10.1021/acsami.7b02803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Dai L.; Liu D.; Du W. Hydrophobic pore space constituted in macroporous ZIF-8 for lipase immobilization greatly improving lipase catalytic performance in biodiesel preparation. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 86. 10.1186/s13068-020-01724-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X.; Fang Y.; Joseph E.; Wang Q.; Li J.; Banerjee S.; Lollar C.; Wang X.; Zhou H.-C. Enzyme-MOF (metal-organic framework) composites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3386–3401. 10.1039/C7CS00058H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H.; Li M.; Gao J.; Zhang Z.; Ma S.; Chen Y. Incorporation of biomolecules in Metal-Organic Frameworks for advanced applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 384, 90–106. 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Lan P. C.; Ma S. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Enzyme Immobilization: Beyond Host Matrix Materials. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1497–1506. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K.; Zhang L.; Chen X.; Liu L.; Zhang D.; Han Y.; Chen J.; Long J.; Luque R.; Li Y.; Chen B. Ordered macro-microporous metal-organic framework single crystals. Science 2018, 359, 206–210. 10.1126/science.aao3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-s.; Xiong Z.-h.; Li C.; Zhang J.-m. Zeolitic imidazolate metal organic framework ZIF-8 with ultra-high adsorption capacity bound tetracycline in aqueous solution. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 82127–82137. 10.1039/C5RA15497A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Dai L.; Liu D.; Du W. Rationally designing hydrophobic UiO-66 support for the enhanced enzymatic performance of immobilized lipase. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 4500–4506. 10.1039/C8GC01284A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.-L.; Lo S.-H.; Singco B.; Yang C.-C.; Huang H.-Y.; Lin C.-H. Novel trypsin-FITC@MOF bioreactor efficiently catalyzes protein digestion. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 928–932. 10.1039/c3tb00257h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.-L.; Wu C.-Y.; Chen C.-Y.; Singco B.; Lin C.-H.; Huang H.-Y. Fast Multipoint Immobilized MOF Bioreactor. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 8923–8928. 10.1002/chem.201400270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]