Abstract

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a deadly and rapidly progressive disease that can present with various paraneoplastic syndromes on initial workup. Acquired factor VIII (FVIII) deficiency, also known as acquired haemophilia A (AHA), has been identified as a rare paraneoplastic syndrome in SCLC. Here, we present a 61-year-old woman with a massive gastrointestinal bleed and prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT) in the emergency department. She was diagnosed with rare paraneoplastic AHA secondary to extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC). She was treated with high-dose steroids and factor bypassing agents, which led to the resolution of bleeding and undetectable FVIII inhibitor levels. She was subsequently treated for ES-SCLC with carboplatin, etoposide and atezolizumab. This case report highlights a rare clinical presentation of paraneoplastic AHA that necessitates prompt recognition in patients with SCLC with ongoing bleeding and elevated PTT.

Keywords: haematology (incl blood transfusion), lung cancer (oncology), GI bleeding

Background

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive malignancy that accounts for 10%–15% of lung cancer cases.1 SCLC has often been associated with paraneoplastic syndromes that produce ectopic hormones or immune-mediated phenomena.2 Acquired haemophilia A (AHA), a rare bleeding disorder that affects 1.3–1.5 cases per million, has been reported as a rare paraneoplastic syndrome associated with SCLC.3 4 Approximately 11.8% of patients with a diagnosis of AHA have an underlying malignancy leading to this paraneoplastic syndrome.5 AHA results from autoimmune response leading to the spontaneous production of IgG autoantibodies targeting factor VIII (FVIII) activity that is an essential clotting factor.6

It is essential to recognise patients with malignancy-induced paraneoplastic AHA to ensure appropriate clinical management. In patients at high risk of a life-threatening bleed, the first goal is to prevent bleeding by avoiding invasive procedures. Active bleeding should be treated with FVIII bypassing agents. The second goal is to eradicate the inhibitor with initiation of immunosuppression, treatment of the underlying aetiology and continued close monitoring of FVIII inhibitor levels. It is important to monitor for sustained FVIII eradication as this can have prognostic value. Retrospective studies show that patients who fail to have complete elimination of the FVIII inhibitor after their cancer treatment have a significantly lower probability of survival.7 Thus, recognition and treatment of paraneoplastic AHA associated with SCLC is crucial for the full eradication of FVIII leading to better prognosis and prevention of catastrophic bleeding.

In this case report, we present a 61-year-old woman who was initially diagnosed with a massive gastrointestinal (GI) bleed. On presentation, she had melena and a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). After multiple bleeding episodes and endoscopic procedures, she was diagnosed with a paraneoplastic AHA secondary to extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC). She was treated with prednisone, recombinant activated factor VII (Niatase) and porcine recombinant VIII (Obizur) by Haematology. This treatment resulted in complete eradication of FVIII inhibitors and resolution of further GI bleeding. Her SCLC was treated with carboplatin, etoposide and atezolizumab. This case report emphasises a rare clinical presentation. In the era of immunotherapy, this case demonstrates continued suppression of a paraneoplastic condition with immunotherapy, in addition to chemotherapy.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old woman presented to the emergency department on 14 June 2019, with fatigue due to severe anaemia, hyperkalemia, acute kidney injury and bilateral lower leg cellulitis. She did not have any significant weight loss. Her medical history included coronary artery disease with a history of pulseless electrical activity requiring coronary artery bypass surgery in 2014, type 2 diabetes and hypertension. She had no allergies. Home medication on presentation was ASA only.

Investigations

On presentation, she was found to be severely dehydrated with an ongoing GI bleed and initial haemoglobin of 46 g/L. Endoscopy showed multiple non-bleeding duodenal ulcers that were treated with high-dose pantoprazole. Her colonoscopy demonstrated non-bleeding submucosal vessels in the cecum and multiple polyps that were removed in the rectum and sigmoid colon. Pathology confirmed hyperplastic colonic polyps but no malignancy. Throughout her hospital admission, she continued to have recurrent episodes of haematochezia and melena with haemoglobin reaching a nadir of 39 g/L. No definite source of bleeding could be identified on upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. She also had a red blood cell scan that did not reveal any sign of bleeding. CT enterography showed extravasation at proximal duodenum. She underwent several arterial embolisations in the duodenal area in efforts to control the possible aetiology of the bleed. Haemolytic workup was negative. She received greater than 30 units of packed red blood cell transfusions during her ongoing bleed episodes in hospital.

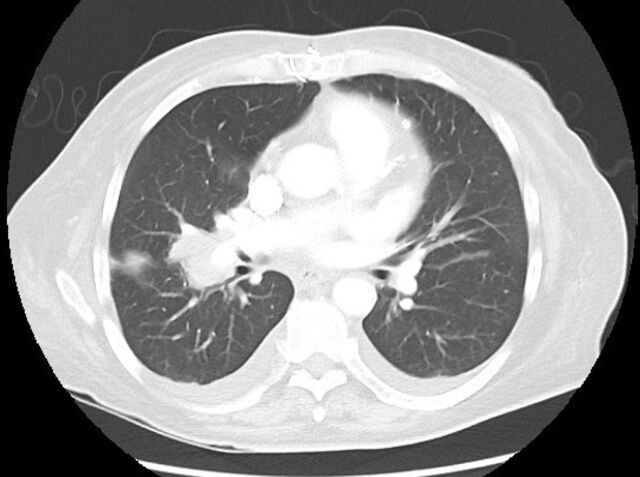

Extensive workup revealed right upper lobe mass and mediastinal lymphadenopathy on a chest X-ray. CT scan showed a 6.1×3.7 cm right hilar mass, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, bilateral pleural effusions and bilateral adrenal metastases as well as intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy (figure 1). MRI of the brain demonstrated a small meningioma but no evidence of metastatic central nervous system (CNS) lesions. Pathology obtained from the left adrenal biopsy confirmed ES-SCLC with synaptophysin weakly positive, and Ki-67 greater than 90%. Additional workup eventually confirmed persistent prolonged aPTT ranging from 39 to 49 s that initiated haematology consult to help explain ongoing bleeding. Please note that the coagulopathy was only detected after the aforementioned procedures and biopsies. Thus, no haemostatic agents were given prior to the procedures or biopsies. However, there was no excessive bleeding reported during or after the procedures and biopsies.

Figure 1.

CT chest shows right hilar mass measuring (6.1×3.7 cm) on 17 June 2019.

AHA was diagnosed on 29 July by Haematology. Her initial FVIII activity was 0.23 units/mL with an inhibitor to FVIII of 6 Bethesda units.

Treatment

She was started on high-dose steroids (prednisone 60 mg orally) on July 30 and received the bypassing agents, recombinant activated factor VII (Niatase) and porcine recombinant VIII (Obizur) replacement, to control the bleeding. During her hospital admission, she continued to have recurrent occult bleeding and melena with fluctuating haemoglobin levels. Thus, she was treated with Niatase and Obizur that were slowly tapered as haemoglobin stabilised and no further evidence of bleeding was demonstrated. She received a total of 140 mg of Niatase (7 mg at a time, 20 doses in total in varied intervals of q2h to q12h (every 2 hours to every 12 hours)). Combination of Niatase and Obizur was used together to control bleeding. She received 40–50 units/kg of Obizur for a total of five doses.

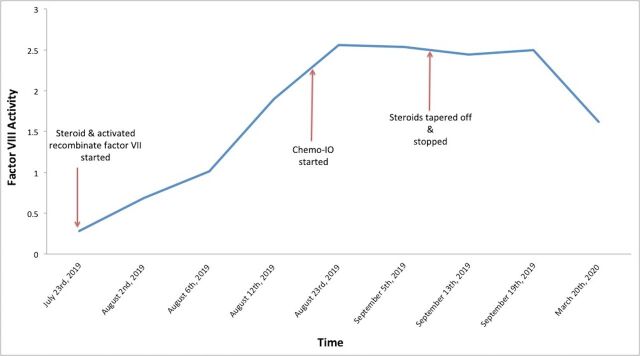

She was started on immunosuppression on July 31, with prednisone 60 mg daily. She demonstrated eradication of the inhibitor by August 12 with undetectable inhibitor and an FVIII level of 1.90 units/mL (figure 2). Her steroids were rapidly tapered and discontinued by mid-September. She was subsequently treated with carboplatin, etoposide and atezolizumab for extensive SCLC when bleeding stopped and she was stabilised clinically. After starting her treatment for lung cancer, her FVIII inhibitors remained undetectable with no evidence of recurrence on prednisone taper.

Figure 2.

This graph illustrates factor VIII (FVIII) activity over time. Steroids were initiated in late July, chemotherapy–immunotherapy (Chemo-IO) was initiated in late August, and steroids were tapered off in mid-September. FVIII inhibitor eradication occurred by August 12, and FVIII level activity remained stable post chemotherapy–immunotherapy.

Outcome and follow-up

Over 1 year after initial presentation, she completed the chemotherapy portion of treatment, and she remained on maintenance atezolizumab. She completed thoracic radiation to the chest and prophylactic cranial irradiation. Her SCLC remained in remission for a year, and FVIII inhibitor levels remained undetectable with no further bleeding episodes. Unfortunately, she recently developed autoimmune myasthenia gravis and died from aseptic meningitis after receiving intravenous immunoglobulin. The most recent imaging was done 1 month prior to her death and showed ongoing stability of her SCLC.

Discussion

AHA occurs due to the development of autoantibodies against autologous FVIII, which can disrupt haemostasis, leading to life-threatening bleeding.8 Approximately 10%–12% of AHA is associated with malignancies, including haematological, colon, pancreatic, rectal, kidney, lung and breast cancer.7 9–13 There are very few cases of lung cancer reported with AHA. The pathogenesis of FVIII inhibitor production in patients with malignancy is not clear. In prior reports, it has been demonstrated that inhibitors driving this mechanism are polyclonal IgG-driven and produced by a B-cell-mediated autoimmune response that leads to paraneoplastic AHA and potential catastrophic bleeding.13 14 Prompt recognition and treatment of paraneoplastic AHA in patients with cancer is vital to reduce the risk of life-threatening bleeding events. Physicians should have a low threshold to consider paraneoplastic AHA workup to rule out FVIII deficiency in patients with a diagnosis of malignancy that present with elevated PTT and bleeding.

The treatment paradigm for SCLC has recently shifted to incorporate immunotherapy, which is the first therapy to show a survival benefit in advanced disease in decades. Response rates of up to 60% can be achieved with first-line atezolizumab, in addition to carboplatin and etoposide.15 Previous case reports have described complete eradication of FVIII inhibitors in the pre-immunotherapy era.16 Our case demonstrates sustained suppression of FVIII inhibitor with chemoimmunotherapy treatment. Atezolizumab is a humanised monoclonal anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody that restores tumour-specific T-cell immunity by interfering with PD-L1 and PD-L1-programmed death signalling.15

Traditionally, patients with prior history of autoimmune disease have been excluded from large phase III clinical trials studying immunotherapy agents due to fear of triggering an autoimmune response.15 Although AHA can be autoimmune in nature, we highlight here a case of paraneoplastic AHA where factor inhibitor levels remained suppressed despite immunotherapy treatment. This case demonstrates that chemoimmunotherapy treatment can be safe in patients with SCLC with paraneoplastic phenomena. In order to promote long-term survival, AHA secondary to solid cancer requires bypassing haemostatic agents, removal of FVIII inhibitor by an immunosuppressive drug and treatment of the underlying malignancy.

In summary, paraneoplastic syndromes are prevalent in SCLC.2 AHA is a rare form of a paraneoplastic syndrome in SCLC. Physicians need to remain vigilant and consider paraneoplastic AHA workup to rule out FVIII deficiency in patients presenting with elevated PTT, bleeding and a lung mass. In patients with SCLC and paraneoplastic AHA whose bleeding has been stabilised and steroids have been initiated, treatment of the underlying SCLC with chemoimmunotherapy can result in sustained suppression of inhibitor levels and haemostasis.

Patient’s perspective.

My symptoms all started in the summer of 2019. I was very fatigued and short of breath with minimal activities. The day I presented to the hospital was a blur to me since I was very sick. I was admitted to the hospital for bleeding and received multiple blood transfusions throughout my stay. I was finally diagnosed with lung cancer and started on treatment for lung cancer as an outpatient. Post-treatment for my lung cancer, I have felt significantly better, and I have not had any issues with bleeding. I am doing very well today. I continue to have a problem only with leg swelling from my congestive heart failure that is presently being managed by my family doctor with Lasix.

Learning points.

Paraneoplastic acquired haemophilia A (AHA) is a rare form of paraneoplastic syndromes in small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Prompt recognition of the paraneoplastic nature of the condition is required to facilitate the treatment of the underlying malignancy.

This report describes the safe treatment of paraneoplastic AHA in the era of immunotherapy for extensive-stage SCLC.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank our patient for allowing us to share her clinical diagnosis on this case report.

Footnotes

Contributors: MP: Contributed to planning, conduct and writing the case report. DE: Contributed to planning, helping with writing/editing the case report. NR and NAN: Contributed to writing/editing the case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lung Health Foundation Lung cancer - lung health foundation - prevention - symptoms [Internet]. Available: https://lunghealth.ca/lung-disease/a-to-z/lung-cancer/ [Accessed 27 Apr 2020].

- 2.Gandhi L, Johnson BE. Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2006;4:631–8. 10.6004/jnccn.2006.0052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins P, Macartney N, Davies R, et al. . A population based, unselected, consecutive cohort of patients with acquired haemophilia a. Br J Haematol 2004;124:86–90. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins PW, Hirsch S, Baglin TP, et al. . Acquired hemophilia A in the United Kingdom: a 2-year national surveillance study by the United Kingdom haemophilia centre doctors' organisation. Blood 2007;109:1870–7. 10.1182/blood-2006-06-029850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knoebl P, Marco P, Baudo F, et al. . Demographic and clinical data in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European acquired haemophilia registry (EACH2). J Thromb Haemost 2012;10:622–31. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04654.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruse-Jarres R, Kempton CL, Baudo F, et al. . Acquired hemophilia A: updated review of evidence and treatment guidance. Am J Hematol 2017;92:695–705. 10.1002/ajh.24777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sallah S, Wan JY. Inhibitors against factor VIII in patients with cancer. Analysis of 41 patients. Cancer 2001;91:1067–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elezović I. Acquired haemophilia syndrome: pathophysiology and therapy. Srp Arh Celok Lek 2010;138:64–8. 10.2298/SARH10S1064E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biesheuvel V, Hiddema SM, Levenga H. Acquired haemophilia A in a patient with breast cancer and lung carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Neth J Med 2019;77:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bossi P, Cabane J, Ninet J, et al. . Acquired hemophilia due to factor VIII inhibitors in 34 patients. Am J Med 1998;105:400–8. 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00289-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Letizia C, Sellini M, Avvisati G, et al. . Acquired factor VIII inhibitor in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the colon-rectum. Ital J Gastroenterol 1991;23:88–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Ismail SA, Parry DH, Moisey CU, et al. . Factor VIII inhibitor and bronchogenic carcinoma. Thromb Haemost 1979;41:291–5. 10.1055/s-0038-1646648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cataldo F, Baudo F, Redaelli R. Acquired factor VIII:C inhibitor (IgG) and positive direct Coombs’ test (IgM) in a patient with lung carcinoma: Clinical course and immunochemical studies. Scand J Haematol 2009;33:171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato R, Hayashi H, Sano K, et al. . Nivolumab-induced hemophilia a presenting as gastric ulcer bleeding in a patient with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:e239–41. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, et al. . First-line Atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2220–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1809064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallah S, Singh P, Hanrahan LR. Antibodies against factor VIII in patients with solid tumors: successful treatment of cancer may suppress inhibitor formation. Haemostasis 1998;28:244–9. 10.1159/000022438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]