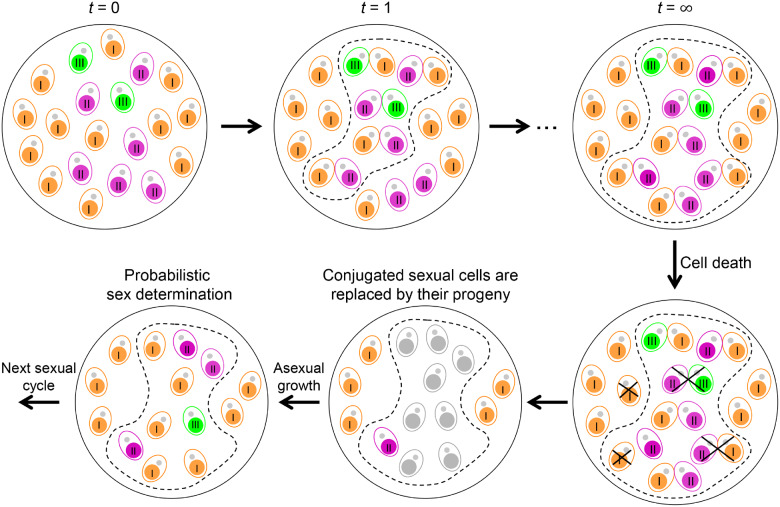

Fig. 1.

Diagram illustrating the mating scheme and dynamics of mating type composition within a population. Each T. thermophila cell contains a MIC (gray dot) and a MAC (colored). MAC colors represent different mating types (I, II, and III in this example). At t = 0, the population initiates a sexual reproduction cycle and all cells become sexually active. After the first round of pairing (t = 1), cells of different mating types pair together (denoted by the dash line). Note that cells of rare mating types tend to find compatible partners more quickly than cells of common mating types. Cells of the same mating type cannot pair and continue to another round of mate-finding until no suitable mates are available. At the end of mating (t=∞), all unpaired cells are of the same mating type, most likely the one with the largest initial frequency. Note that some paired cells may separate and may not find a partner in the current sexual cycle. Both conjugated cells and unpaired cells undergo viability selection and some will die due to developmental failure and/or starvation stress (used to induce sexual reproduction). Surviving conjugated cells are replaced by their sexual progeny. After sufficient rounds of asexual growth to reach sexual maturity, each sexual progeny cell will develop into a specific mating type, the probability of which is determined by the mat allele. A new sexual cycle is then induced.