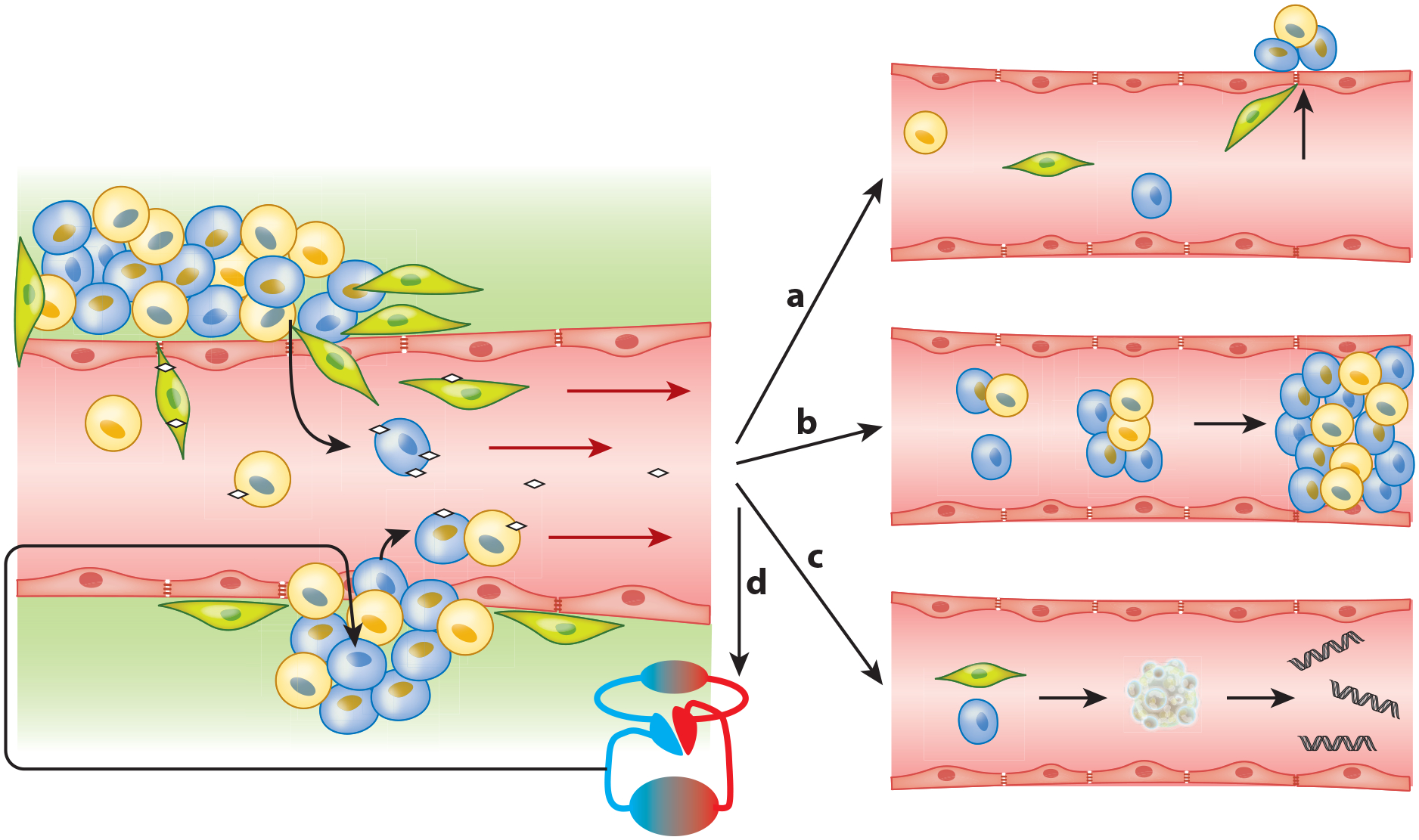

Figure 3.

Proposed circulating tumor cell (CTC) dissemination into the vasculature and subsequent prospects. (Left) Epithelial heterogeneous tumors shedding tumor cells into the bloodstream. Such shedding can be passive (bottom) as parts of the tumor (fragile vessels) break off, thereby shedding epithelial CTCs (blue and yellow) into the blood, sometimes even as circulating tumor microemboli (CTM). Alternatively, shedding may be active (top) as cells undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (green, EMT-CTCs), which may happen partially or completely and is often induced by platelet interaction (little white diamonds) (24). As these EMT-CTCs actively penetrate into the blood vessel, some epithelial cells may passively follow (73), driven by the bloodstream-induced low pressure. Once within the vasculature, a CTC has multiple fate options. (Right) (a) Cells that underwent partial or full EMT may reverse this process and start mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition as part of metastasis formation (73). However only 0.01% of CTCs are likely to form a metastasis at a distant site (92). (b) CTM and CTCs in the vasculature may get stuck in blood vessels and are suspected to have a role in causing venous thromboembolism (83). Additionally, CTM may initiate metastatic growth after lodging in a distal capillary (74, 87). (c) CTCs (epithelial or mesenchymal) may undergo apoptosis, which releases circulating tumor–derived DNA into the bloodstream. (d) After survival in the vasculature, CTCs may self-seed. This process is often observed and is supported by the CTC-friendly microenvironment of the primary site (95, 97).