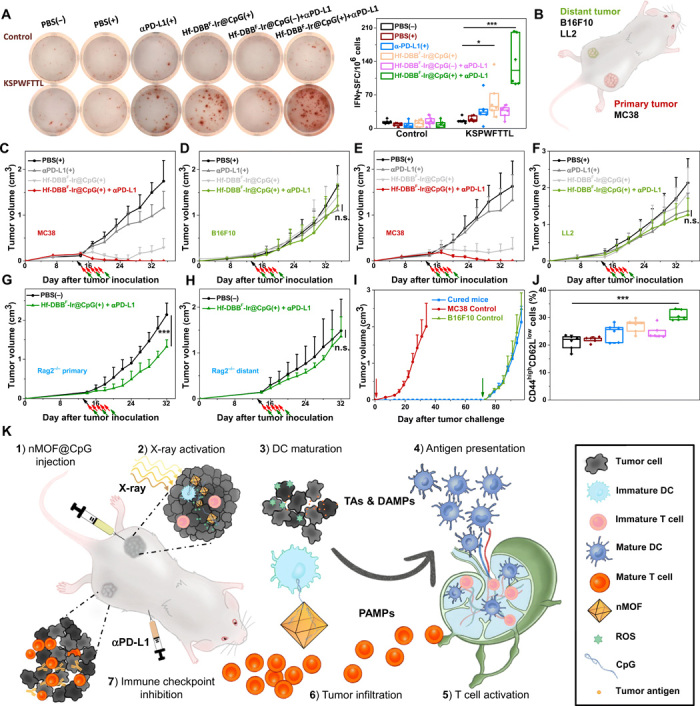

Fig. 6. Specificity and immune memory effect of in situ cancer vaccination plus CBI.

(A) Representative images of colonies (left) and statistical analysis (right) of ELISpot assay performed to detect tumor-specific IFN-γ–producing T cells; n = 6. SFC, spot-forming cells. (B) Schematic illustration of bilateral models established by subcutaneous injection of MC38 and B16F10 or LL2 cells onto flanks as primary and distant tumors, respectively. Primary treated MC38 (C and E) and distant untreated [B16F10 for (D) and LL2 for (F)] tumor growth curves on unmatched bilateral tumor models treated with PBS(+), αPD-L1(+), Hf-DBBF-Ir@CpG(+), or Hf-DBBF-Ir@CpG(+) + αPD-L1; n = 4. Primary (G) and distant (H) tumor growth curves on MC38-bearing Rag2−/− models treated with PBS(−) or Hf-DBBF-Ir@CpG(+) + αPD-L1; n = 6. (I) Tumor growth curves after challenge with MC38 tumor cells and rechallenge with B16F10 cells on cured mice as treated from Fig. 5C. (J) Percentages of CD44highCD62Llow cells with respect to the total splenocytes; n = 6. (K) Schematic illustration of antitumor effect of in situ cancer vaccination by nMOF(+) plus CBI. (1) Hf-DBBF-Ir@CpG is intratumorally administered in the primary tumor. (2) Upon x-ray activation, Hf-DBBF-Ir generates ROS to induce ICD to expose tumor antigens and DAMPs, while cationic Hf-DBBF-Ir delivers CpG as PAMPs to APCs. (3) DAMPs and PAMPs promote DC maturation. (4) Tumor antigens are presented by mature DCs onto T cell in tumor-DLNs. (5) T cells expand and infiltrate to both primary and distant tumors. (6) Systemically administered immune checkpoint inhibitor αPD-L1 attenuates T cell exhaustion.