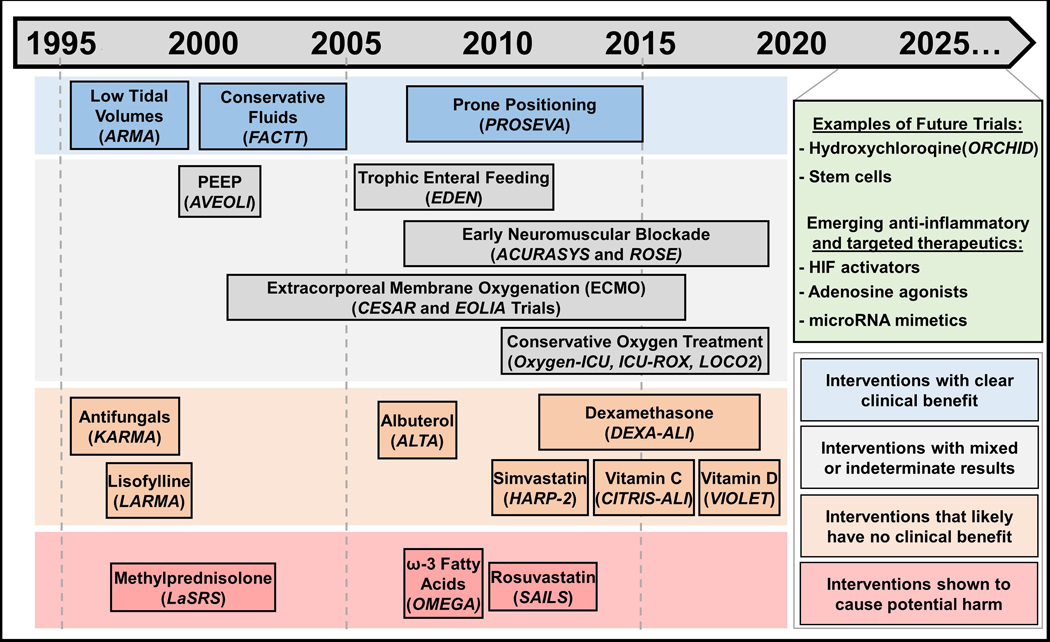

Figure 1:

A summary of 25 years of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) intervention trials. Interventions are chronologically displayed with corresponding clinical trials italicized underneath and color-coded to denote clinical efficacy. Interventions that have clear clinical efficacy, in blue boxes, include the use of small tidal volumes,9 prone positioning,20 and restrictive fluid administration,37 which have demonstrated clear mortality or ventilator-free days benefits. Interventions in grey boxes include those that have mixed results from different trials, as is the case for conservative oxygen treatment32,33,75 and early neuromuscular blockade.38,39 This category (grey boxes) also includes interventions with indeterminate results, such as the case for Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP)15 – itself is a component of lung-protective ventilation, but the appropriate amount to use is still contended – or those that have value in ARDS patients aside from improving ARDS outcomes, such as early trophic enteral nutrition to prevent gastric intolerance40 and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) as a rescue therapy.35,36 In orange boxes are interventions that failed to demonstrate improvements in ARDS outcomes, such as antifungals, lisofylline, albuterol, simvastatin, vitamin C and vitamin D.41–47 Dexamethasone is also listed in this category given that the DEXA-ALI trial was conducted in an unblinded fashion28 and prior randomized trials showed no clinical efficacy for steroid administration in ARDS. Methylprednisolone,27 rosuvastatin49 and ω−3 Fatty Acids,48 listed in red boxes, have shown to cause potential harm in randomized controlled trials. Currently, ongoing or planned trials and emerging therapeutic targets are displayed in green.