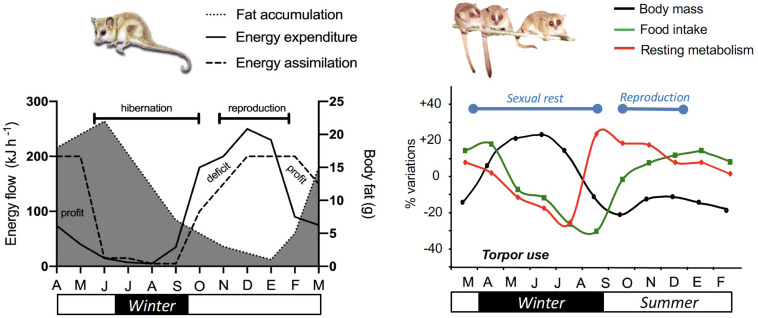

FIGURE 3.

Hypothetical (but realistic) annual budget of energy and activity in monitos and mouse lemurs. Curves for South American monito del monte (Dromiciops gliroides) (left panel) are based on several descriptions of the reproductive cycle (Muñoz-Pedreros et al., 2005), seasonal variations in activity, adiposity and body mass (Celis-Diez et al., 2012; Franco et al., 2017) and food availability (Franco et al., 2011; di Virgilio et al., 2014). After reproduction in March (end of summer), monitos start to reduce activity and energy expenditure, and accumulate almost twice their body size in fat (Franco et al., 2017). The net annual energy balance is usually close to zero and varies depending on cold winter temperatures, allowing torpor to occur. Annual variations of body mass, MR (Perret, 1997) and food intake in captive male mouse lemurs (Microcebus murinus) native to Madagascar (right panel) show drastic changes across seasons, similar to that observed in wild conditions. At the beginning of winter, male mouse lemurs make extensive use of daily torpor to save energy and therefore fatten to increase their body mass by ∼40%. They reach a plateau in the middle of winter and spontaneously increase their MR while food intake is still low. Such changes coincide with the recrudescence of the reproductive axis, and lead to body mass loss. High MRs during and after mating season are supported by increased foraging, thus leading to stable body mass throughout the summer.