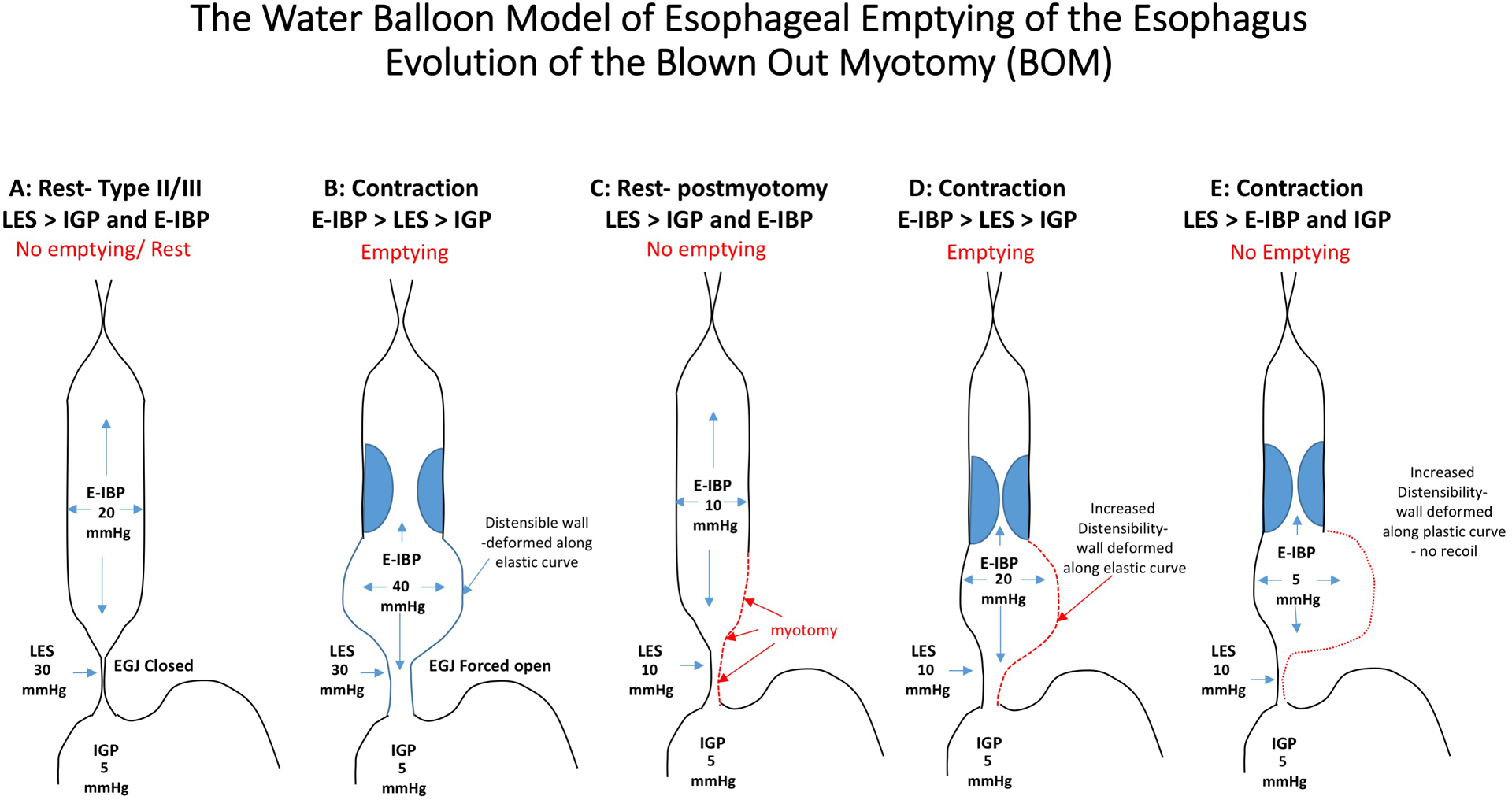

Figure 3.

Panels A and B: Patients with type II and III achalasia generate high esophageal intrabolus pressure (E-IBP) through non-propagating contractions that reduce the lumen volume and this generates a high pressure in the esophagus (panesophageal pressurization or compartmentalized). The esophageal wall is distensible and elastic and the wall can accommodate the pressure increase by passively distending (Panel B) and recoiling back to its normal state (Panel A). This can generate enough pressure to open the poorly relaxing lower esophageal pressure (LES) and overcome the intra-gastric pressure (IGP). After a myotomy (Panels C-E), the pressure generated in the esophagus is lower because the myotomy reduces the outflow obstruction and the LES can open wider at lower E-IBP. However, there is still some resistance to flow related to the hiatus opening, anti-reflux surgery or an incomplete myotomy and the E-IBP will preferentially distend the area of the esophageal body where the myotomy was performed (Panel D). Continual stretch of this segment may eventually lead to remodeling in the are of the previous myotomy and the tissue may loose its elastic properties and the wall will deform and become more plastic (Panel E). This segment loses the ability to recoil and generate high E-IBP despite contractions and emptying is impeded by the inverted pressure gradient and the inability to generate a sufficient intrabolus opening pressure at esophagogastric junction. (Note: values depicted are to aid in conceptual understanding only)