Abstract

Objective

Brain Age Index (BAI), calculated from sleep electroencephalography (EEG), has been proposed as a biomarker of brain health. This study quantifies night-to-night variability of BAI and establishes probability thresholds for inferring underlying brain pathology based on a patient’s BAI.

Methods

86 patients with multiple nights of consecutive EEG recordings were selected from Epilepsy Monitoring Unit patients whose EEGs reported as within normal limits. While EEGs with epileptiform activity were excluded, the majority of patients included in the study had a diagnosis of chronic epilepsy. BAI was calculated for each 12-hour segment of patient data using a previously established algorithm, and the night-to-night variability in BAI was measured.

Results

The within-patient night-to-night standard deviation in BAI was 7.5 years. Estimates of BAI derived by averaging over 2, 3, and 4 nights had standard deviations of 4.7, 3.7, and 3.0 years, respectively.

Conclusions

Averaging BAI over n nights reduces night-to-night variability of BAI by a factor of , rendering BAI a more suitable biomarker of brain health at the individual level. A brain age risk lookup table of results provides thresholds above which a patient has a high probability of excess BAI.

Significance

With increasing ease of EEG acquisition, including wearable technology, BAI has the potential to track brain health and detect deviations from normal physiologic function. The measure of night-to-night variability and how this is reduced by averaging across multiple nights provides a basis for using BAI in patients’ homes to identify patients who should undergo further investigation or monitoring.

Keywords: Brain Age, Brain Health, EEG, Sleep, Night-to-Night Variability

1. Introduction

There are several dimensions of measurable brain health, including subjective complaints, neuropsychological testing (Lezak 2012), cerebral oxygen extraction and blood flow (Xu et al. 2009), brain structure using magnetic resonance imaging (Carne et al. 2006), and electroencephalographic (EEG) markers (Al Zoubi et al. 2018). The latter may be measured during wake or sleep. Wake characteristics of abnormal brain function include pathological slowing and abnormalities of alpha wave frequency and distribution. Sleep markers of brain health include spindle and delta power and K-complexes characteristics, which reflect health of the < 1 Hz non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep slow oscillation (Urakami et al. 2012). However, in isolation these biomarkers have shown only weak associations with disease state, and only at the group level.

The brain age index (BAI) is an algorithm for measuring how much an individual’s electroencephalographic (EEG) brain activity during sleep differs from the expected pattern for an individual’s age, based on many features extracted from different sleep stages and the resting awake state.

BAI is derived by first producing an estimate of the individual’s age from an overnight sleep EEG, called the brain age (BA), and subtracting from this the individual’s chronologic age (CA). Prior studies showed that BAI provides a stable longitudinal estimate of brain aging on a population level. In these studies, BA was shown to correlate strongly with CA, and excess BA (BAI>0) was found to be associated with conditions that worsen brain function (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, dementia, psychiatric disease) (Sun et al. 2019). Excess BA is also a predictor of reduced life expectancy (Paixao et al. 2020). Thus, BAI holds promise as a biomarker of brain health.

However, before BAI can be applied in individual patients, it is necessary to understand its night-to-night variability, or its converse, night-to-night stability. Nightly variation in sleep EEG patterns may arise from either short-term factors not strongly related to long-term brain health—such as light or noise, body position, recent sleep loss—or other sleep disturbances (Brunner et al. 1993). By contrast, “brain health”, as influenced by long-term exposure to factors such as cerebrovascular or neurodegenerative disease, chronic intermittent hypoxia from sleep apnea, inflammatory states, exercise, nutrition, or long-term sleep habits, is expected to vary more slowly, perhaps over the course of weeks to months or even years, but to be relatively stable on a night-to-night time scale. If BAI shows high night-to-night variability, then it may be advantageous to measure BAI several nights in a row and average the measurements, to derive a meaningful biomarker of brain health more applicable at the level of individuals. By this reasoning, the degree to which a high BAI value should be considered “abnormal” depends on the extent to which it exceeds expected levels of night-to-night fluctuation.

In this study, we therefore aimed to: (1) determine the night-to-night variability of BAI in individual patients, and (2) establish thresholds for the probability of underlying brain pathology based on a patient’s BAI, i.e. values of BAI above which concern and further investigation are warranted. We hypothesized that averaging BAI estimates across multiple nights would increase algorithm stability and allow detection of potential brain pathology on an individual level.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Selection Criteria

For this study, we obtained data from adult patients who underwent multi-day EEG recordings during the course of routine clinical care but were not acutely ill. The Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) provides such a cohort. Patients admitted to the EMU include a mixture of those with established epilepsy, and those being evaluated to determine whether or not they have epilepsy. A portion of patients admitted to the EMU have normal EEGs. Some of these are patients with epilepsy whose burden of seizures and epileptiform activity is low, while others are ultimately found to have problems unrelated to epilepsy (e.g., behavioral / psychogenic events or cardiac events masquerading as seizures). EEG data from these patients provide a unique opportunity to use existing clinical data to estimate night-to-night variability of EEG-based BA in EEGs that are free of epileptiform. We excluded EEGs with epileptiform activity, because these might impair the automated sleep-staging algorithm, which is an important part of calculating BAI.

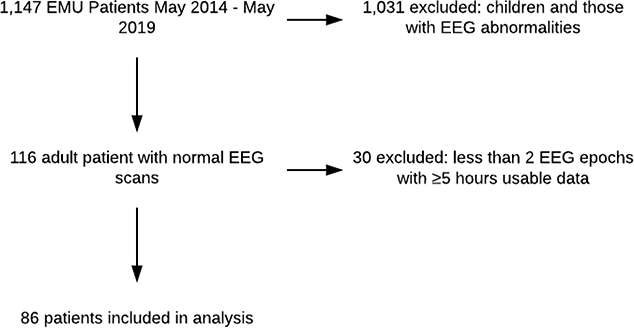

We therefore used the following criteria to select patient data for our present study: eligible subjects included any adult patient (≥ 18 years) who underwent continuous EEG (cEEG) monitoring at the Massachusetts General Hospital EMU between May 1, 2014, and May 1, 2019, who had (1) at least two consecutive nights of EEG recordings; (2) the EEG recordings were “normal” (i.e., showed no signs of epileptiform EEG activity, as such abnormalities would affect the calculation of BA) as determined by the clinical report signed by the attending clinical neurophysiologist; and (3) at least five hours of usable cEEG data for each 12-hour period. The median length of usable data for each epoch was 9.9 hours (IQR [9.0–10.6]). While no EEGs containing epileptiform activity were included, patients with a diagnosis of epilepsy were not excluded. Patients with a diagnosis of epilepsy were included if their EEGs during the EMU stay did not contain epileptiform activity. Out of 1,147 patients admitted to the EMU during the 5-year period, eighty-six patients met the inclusion criteria. A patient selection flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1-.

Patient Selection Flowchart.

The Partners Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective analysis without requiring additional consent for its use in this study.

2.2. Patient Cohort

Previous MRI studies show that epileptic patients’ brains appear to show structural signs of accelerated biological aging (Pardoe et al. 2017; Sone et al. 2019). To test whether this observation also applies to BAI, we examined whether BAI differs in patients with vs without epilepsy. For this comparison we used a one-sided, two-sample Welch’s t-test, with the hypothesis that epileptic patients would have a higher average BAI than those without epilepsy.

After observing a non-significant difference in mean BAI, we performed a power analysis a power analysis to calculate the minimum sample size required to detect a difference in means of 2.6 years (10.2 years for epileptic patients −7.6 years for non-epileptic patients) with 80% power at a significance level of 0.05 given the standard deviation in BAI between patients (SD=9.52).

2.3. EEG Preprocessing and Artifact Removal

Our study used 6 channels for sleep-staging: frontal (F3 and F4), central (C3 and C4), and occipital (O1 and O2). The EEG signals were notch-filtered at 60Hz and then bandpass filtered from 0.5 – 20Hz. EEG signals were divided into 30-second segments for analysis. Each 30-second segment was marked as artifact and removed if the segment contained two or more seconds of saturated signal (amplitude greater than 500μV), or five or more seconds of flat EEG signal (standard deviation of the amplitude less than .2 μV for five seconds, or less than 1 μV for the whole 30-second segment).

2.4. Sleep Staging

To classify EEG epochs into sleep-stages, a previously published extreme learning machine (ELM) based model, trained on a dataset of 2,000 PSGs, was used (Sun et al. 2017). This algorithm classifies each 30-second EEG epoch into one of five stages: awake, NREM1, NREM2, NREM3, or REM. When tested on a dataset of 1,000 patients, and compared with human scoring, this algorithm had a Cohen’s kappa of 0.68. This is comparable to inter-rater agreement among experts for expert sleep-staging according to American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines, which was 0.76 among eight European centers and 0.63 among nine international centers (Danker-Hopfe et al. 2009; Magalang et al. 2013).

2.5. Removing Eye-open Awake Signals

The brain age algorithm was trained on data from patients in a sleep lab setting, consisting primarily of eyes-closed, in-bed periods, whereas the EMU EEG data used in the present study also includes prolonged periods when patients are active and awake. Awake segments during which the patient is resting are used by the BAI algorithm, which we define as eye-closed awake data in our study. To render the data appropriate for the BAI algorithm and remove segments containing physical activity, eyes-open awake epochs were removed using an automated process. This process uses a customized blink detection algorithm, as follows: After sleep staging, ten randomly-selected, one-minute awake EEG segments were hand labeled for blinks, and a parameter search was performed to optimize a threshold for peak detection (Gramfort et al. 2013, 2014), used in a blink-detection algorithm developed by MNE (a signal-processing software suite named for its ability to calculate Minimum Norm Current Estimates) (Gramfort et al. 2013). This algorithm first filters the signal using a Finite Impulse Response and a band pass filter and then detects peaks. We used bipolar montage channels Fp1-F3 and Fp2-F4 channels in the blink detection routine. MNE source code can be found here (Larson 2019b, 2019a).The optimal threshold was 90μV, with a Cohen’s kappa value of 0.83.

To remove eyes-open awake data, 30-second epochs which (1) contained greater than six blinks and (2) were classified as awake by the ELM based sleep-staging model were removed. While EEG information is lost by excluding eye-open awake data, the BA algorithm relies on EEG patterns found during sleep and while a patient is resting. To ensure that adequate information is present in each epoch to estimate BA, after removing eyes-open awake epochs, only EEG epochs with at least five hours of usable data were included. The mean number of available 5-hour epochs per patient during their EMU stay was 5.6 (SD=3.4). For all 12-hour epochs included in the study (those with at least 5 hours of usable data), 17.3% of the recording time was classified as either artifact or eye-open awake and removed.

Since the number of blinks per minute varies depending on activity, we tested both higher and lower blink thresholds (3 and 9 blinks per 30 seconds respectively) when removing eye-open awake data. To determine whether night-to-night BAI stability estimates are affected by different blink thresholds, we recalculated BAI for all patients using both thresholds, and calculated intrapatient variation in BAI.

2.6. Brain Age Calculation

An individual’s brain age is determined by examining sleep-EEG features. There were 96 features for each 30-second epoch (6 sample entropy features are omitted for computational time consideration compared to the 102 features in Sun et al. 2019), which were averaged for each sleep stage (including awake and REM) and concatenated for a total of 480 features. The algorithm uses only micro features derived from the EEG. Features include those calculated from the waveform and the spectrogram (relating to the EEG directly). Waveform features include standard deviation, kurtosis, line length and spectral features include bandpowers, ratios between bandpowers, and kurtosis of bandpowers. After calculating the 480 features, these features were Z-normalized with reference to training feature data. This ensures that features are relatively invariant to the choice of reference. In this algorithm, all 480 features are equally weighted. Since a majority of the features are calculated from asleep data, this has a larger impact on BAI calculation than features derived from awake data.

This model was trained on a dataset of 1,343 patients and evaluated on a test set of 1,189 patients. In this test set, BA was highly correlated with CA (r=.84). The algorithm also shows longitudinal stability at a population level: when tested on the Sleep Heart Health Study dataset containing EEGs 5.2 years apart, the average patient increase in BA was 5.4 years. For additional details please refer to Sun et al. 2019.

Similar to MRI-based brain age estimates, our model has a bias which tends to overestimate younger patients’ BA and underestimate older patients BA, so linear bias correction based on patient age was applied to all patients’ according to recent bias correction recommendations (Beheshti et al. 2019; de Lange and Cole 2020). This correction was performed using the same values used by Sun et al. in 2019.

2.7. Brain Age Summary Analysis

After calculating mean BAI, we calculated the correlation between CA and BA, and examined whether variability in BA changed with increasing CA. To determine whether BA variability changed with increasing CA, we separated patients into six groups based on CA (15–25,…,65–75). Then we ran the Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric ANOVA test alternative) comparing standard deviation in BA for each of the six groups to determine whether the mean variation in BA changed with age. We further completed a 2-sample t-test comparing the mean BAI in our patient cohort to the mean BAI in the MGH training dataset.

After observing an unusually high average BAI for this patient cohort, we examined model feature effect sizes to discover what features contribute to increased BAI in our dataset when compared to the original training dataset, for which mean BAI was 0. This is possible because the BAI prediction algorithm is a linear model. To do this, we calculated the average value over all patients of each of the 490 features for the original training dataset and our dataset. We then multiplied these average feature values by the model coefficient. The feature value times the model coefficient represents each feature’s overall contribution to BA. We then subtracted our dataset’s feature contributions from the training dataset’s feature contributions (our data feature averages – MGH training data feature averages) for each feature to get the average contribution of each feature to BAI. Thus, features with a positive difference in feature contribution are those responsible for increased BAI in our dataset when compared to the training dataset. We refer to the difference in feature contribution between our dataset and the training dataset as feature effect size. The sum of all feature effect sizes represents the average difference in BAI between our dataset and the MGH training dataset.

We hypothesized that low EMU sleep quality would affect BAI, we explored factors associated with deep sleep in N3. Since with a decrease in delta and theta power is associated with increased age in our model and in recent literature, we calculated the sum of feature effect sizes for all features involving N3 sleep and either delta or theta waves (Carrier et al. 2001). We then divided the sum of feature effect sizes for N3 delta/theta features by the sum of all feature effect sizes to get the percent increase in BAI explained by N3 delta/theta features.

2.8. Within-patient Night-to-Night Variability in Brain Age

EEG features and sleep-stages are required inputs for calculating BAI. Features were calculated using previously published methods (Sun et al. 2019). The previous study used frontal (F3-M2 and F4-M1), central (C3-M2 and C4-M1) and occipital (O1-M2 and O2-M1), with each channel referenced to the contralateral mastoid. Our study used the same 6 channels: frontal (F3 and F4), central (C3 and C4) and occipital (O1 and O2), except that the reference channel was C2 (second cervical vertebra) rather than the contralateral mastoid (Lepage et al. 2014); this is the standard reference electrode in our institution’s EMU. Standard 10–20 electrode placement was used: a list of the 19 channels used in the EMU is provided in the Supplementary Material. However, it should be noted that both BA calculation and sleep-staging use the same six channels (‘F3’, ‘F4’, ‘C3’, ‘C4’, ‘O1’, ‘O2’). Fp1 and Fp2 were used to detect blinks, and the other eleven channels were not used in this analysis.

Our goal here was to quantify variability of BAI for a patient that has had multiple close-in-time sleep EEGs (spaced apart by no more than a few days), hence multiple BAI estimates. We propose both a “theory” and an empirical approach to verify the theory:

2.8.1. Signal + Noise theory of multi-night BAI variability:

We hypothesized that BAI measurements taken within a few days of each other can be modeled as a constant, the “true” underlying value of the BAI, plus independent noise:

| (1) |

We assume that the noise is normally distributed with zero mean, ϵ~N(0,σ2), where σ2 is the variance, to be estimated. Under this simple model, when more than one BAI measurement is available , , we average the measurements to obtain an estimate with a higher signal to noise ratio, . Under this model, the standard error of the mean 〈BAIn〉 decreases as , thus

| (2) |

Our primary objective is to estimate the standard deviation of BAI measurements, σ. We note that the assumption that the data follow a normal distribution, shown in Equation (2), is not strictly required for the variance to decrease as proposed. Nevertheless, we make this assumption for simplicity and subsequently verify that it provides a reasonable empirical fit to the data.

2.8.2. Empirical approach to multi-night BAI variability:

We take an empirical approach to verifying the theoretical model previously described. For explanatory purposes, we choose an example patient who has 7 independent measurements of BAI from 7 nights of EEG data (Figure 2). Since the objective is to characterize how averaging multiple independent BAI estimates reduces within-patient standard deviation in BAI, we calculate the within-patient standard deviation of BAI measurements that are averaged over n nights, where n refers to the number of independent estimates that are averaged to create a composite measure of BAI, not the total number of measurements a patient has. For the case where n =1, a single BAI estimate is computed for each night (no averaging) and the standard deviation is calculated using unaveraged BAI estimates. In cases where n is greater than 1, BAI estimates are calculated by averaging n independent BAI calculations, and the standard deviation is calculated using BAI values averaged over n nights. We calculate standard n deviation for unaveraged and averaged BAI values to validate our hypothesis that the standard error, and thus BAI estimate variability, will decrease with an increasing number of nights averaged.

Figure 2-.

Diagram showing how the standard deviation in Brain Age Index (BAI) was calculated for n = 1, 2, 3, and 4 nights for a single patient. For n = 2–4, each procedure was repeated using 1,000 random permutations, and the results were averaged.

When n =1, we calculate the standard deviation in BAI estimates without averaging. For an example patient with seven nights of data, this would simply be the standard deviation of these seven estimates (Figure 2a).

Next, consider the case where BAI estimates from multiple nights are averaged together to arrive at a less noisy BAI estimate. We explain our approach beginning with the case where n = 2 (Figure 2b). To estimate the standard deviation of averages based on pairs of BAI measurements, we partition each patient’s single-night BA estimates into groups of two. We use the word partition deliberately: to ensure that our estimates of variability are not downwardly biased, we do not take all possible pairs of two; rather, we allow any single observation to show up in only one pair of measurements. For a patient with seven BA estimates, we calculate 3 means of BA estimates using 3 pairs: 1–2, 3–4, and 5–6, with BA estimate 7 not used (Figure 2b). The within-patient standard deviation of these pair-based (n =2) average BAIs is the standard deviation of these three independent values. Note that we do not consider all pairs of size 2 when calculating the standard deviation (of which there are 21) because many of those pairs (18 out of 21) would have an observation which shows up in at least one other pair, which would cause the mean calculated from those 2 pairs to be correlated and bias the estimated variability downward.

When n =3, we partition the sample into groups of 3 independent BAI measurements (Figure 2c). We then calculate the average BAI for each of these groups. For our example patient, BAI estimates would be separated into two groups—containing estimates 1, 2, and 3; and estimates 4, 5, and 6—and groupwise average BAIs would be calculated. The within-patient standard deviation for this patient when n =3 is the standard deviation between the two average BAI estimates (Figure 2c).

For a patient with seven BA estimates, note that we could not calculate the standard deviation of BAI if n = 4 nights, because there aren’t enough estimates to calculate two independent means of BAI which use 4 nights each. Thus, the standard deviation for estimates of BA obtained by averaging 4 (or n) nights is only calculated if patients had at least 8 (2n) nights of EEG data (Figure 2d).

The above procedure is not ideal in that information is lost when excess nights are excluded when calculating the standard deviation. To use all information present when calculating standard deviation in BAI, the stated procedure—partitioning each patient’s BA estimates into groups of size n, taking the average BAI for each group, and calculating the standard deviation of group averages—is repeated 1,000 times per patient using random permutations, and the average within-patient standard deviation in BAI is used for each patient. For example, when n =2, we randomly reorder the 7 nights so that the order is 5,3,4,1,7,2,6. Then we partition the values into groups of size 2 ((5,3), (4,1), (7,2)), average each of these pairs, and calculate the standard deviation between the pairs of estimates. Permuting the order of nights allows us to estimate the intra-patient variability when different individual BAI estimates are averaged while also ensuring that the same night does not show up more than once when calculating a single standard deviation. We repeat the procedure 1000 times to calculate an average standard deviation independent of permutation order.

2.9. Effect of Sleep Stage distribution on BAI Variability

To understand whether BAI variability is related to the percent of time spent in each sleep stage across multiple nights, we first calculate the stage distribution (percent of time spent in each sleep stage) for each night for each patient. We used the percent of time spent in each sleep stage for each patient for each night as explanatory variables when trying to predict a patient’s standard deviation in BAI. To capture potential non-linear relationships and interactions between variables, we trained a Random Forests model on 70% of the BAI estimates (n=336). We then generalized these predictions to the remainder of the BAI estimates (n=144) and calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient.

2.10. Analysis of “First Night Effect” on BAI Variability

Since sleep quality is known to be disrupted on the first night away from home, we examined whether the first-night effect has a significant impact on BAI variability. First, we removed first night data from the dataset, and recalculated standard deviation in BAI for the subset of patients with greater than 2 epochs (n=68). Then, we calculated the standard deviation in BAI for the same group of patients without removing first night data. Since we included only a subset of patients when calculating the standard deviation in BAI in this analysis, standard deviation values including the first night are slightly different from those obtained when all patients are included.

We repeated this procedure (removing first-night data and recalculating standard deviation in BAI), using the method described above (permuting, partitioning, and averaging independent BAI estimates) to calculate standard deviation both with and without first-night data for n=2, 3, and 4.

We then calculated the difference in standard deviation after excluding the first night (SD excluding first night – SD including first night) to see how stability changed. Thus, negative differences represent decreased stability when first-night BAI estimates are included.

We also calculated average patient sleep efficiency for the first night and compared this to average patient sleep efficiency over all other nights to determine if there was a significant decrease in sleep efficiency on the first night.

2.11. Defining Brain Age Risk Lookup Table

Using the mean intra-patient standard deviation for n =1, 2, 3, and 4 nights, we calculate the probability that a patient’s true BAI (the BAI estimate based on an infinite number of nights) would be equal to their BAI estimate. The purpose of this table is to assist in determining whether an individual patient’s BAI may be considered “normal” or whether their BAI is cause for clinical concern. Adopting a Bayesian framework allows us to use a prior distribution (our belief as to the true distribution of BAI without any observation) and observed data to create a posterior distribution of BAI (the prior distribution after being modified to fit observed values). This is valuable because it allows us to estimate the true distribution of BAI without a ground truth to compare against.

We also assume that, conditional on the patient’s true BAI, the distribution of BAI estimates is randomly distributed around that true BAI, according to Equation (1) . In other words, we assume that a patient’s varies from their true BAI based on random noise and thus estimates are normally distributed around a patient’s true BAI. As for the prior distribution over values of BAI, we assume it is uniformly distributed on an interval [L,U], with L and U as lower and upper limits in BAI respectively. This choice of prior avoids any strong assumptions regarding whether patients undergoing BAI testing are from a healthy vs. sick population, in line with our goal of using BAI as a biomarker of brain health across a wide range of patients. Given this assumption, we apply Bayes rule to make inferences about a patient’s actual BAI (modelled by the posterior distribution) given their BAI estimate, :

| (3) |

Under the assumption that the distribution of BAI estimates——is normally distributed around a patient’s true BAI and the true distribution of patient BAIs—P(BAI)—is uniformly distributed, the posterior distribution is (approximately) a normal distribution. Thus, according to Equation (3), the probability distribution of a patient’s true BAI is normally distributed around an unbiased estimate of BAI. Note that the posterior distribution is technically a truncated normal distribution; however, to reflect a lack of strong conviction regarding the true BAI’s distribution, choosing a large interval [L,U] for the uniform distribution approximately results in a normal distribution (the lower and upper bounds of BAI are three standard deviations below and above the mean in our calculation).

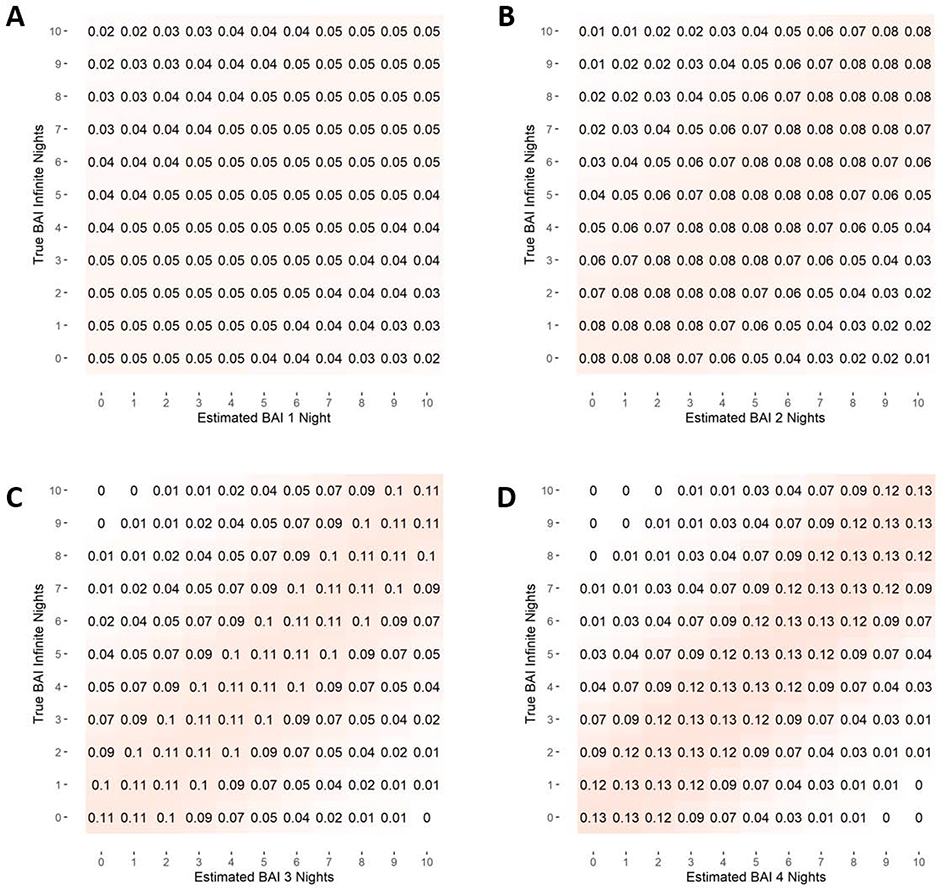

Using the normal distribution, the average standard deviation in BAI estimates was then used to calculate the probability that a patient’s BAI is equal to a certain value y, given that their estimate of BAI is equal to x. These results are reported as a probability density table (Figure 3). To facilitate usability within real world clinical and research contexts, we also calculated the probability that a patient’s true underlying BAI is greater than or equal to a certain value y, given that their BAI estimate is equal to x. These results are presented in the brain age risk lookup table (Figure 4). Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material provides a visual representation of how individual probabilities were calculated using the normal distribution.

Figure 3-.

Table of probability density. The probability that a patient’s true Brain Age Index (BAI) is equal to (± .5 years) their estimated BAI if (1) no averaging is performed, or (2) estimates are averaged over 2, 3 or 4 nights.

Figure 4-.

Table of risk probability that a patient’s true Brain Age Index, or BAI, (based on infinite nights of EEG recordings) is greater than or equal to their estimated BAI if (1) no averaging is performed, or (2) estimates are averaged over 2, 3 or 4 nights.

2.12. Calculating Probability of Increased BAI for Individuals in Our Patient Cohort

To explore whether patients in our study have significantly high BAI values, we calculated the probability that each patient’s true BAI value is greater than or equal to 4 (the increase in age observed in cohorts with neurological disorders) and the probability that their true BAI value is greater than or equal to 9.5 (one SD increase in BAI above 0, suggestive of reduced life expectancy). These values were calculated using a truncated normal distribution based on a patient’s mean BAI values, the average SD in BAI for the whole patient cohort (7.5 years), and the number of independent BAI estimates a patient had. When calculating the risk that a patient’s BAI was greater than or equal to a threshold, the procedure used to create the BAI risk table was utilized.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohort

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Sleep stage summary values are found in Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| Patient Characteristics | |

| n | 86 |

| Number of Epochs (mean (SD)) | 5.58 (3.41) |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 41.97 (13.84) |

| Mean BAI (mean (SD)) | 9.50 (9.52) |

| Female Gender (%) | 56 (65.1) |

| White Race (%) | 81 (94.2) |

| Medical History | |

| Epilepsy (%) | 63 (73.3) |

| Hypertension (%) | 35 (40.7) |

| Tobacco (%) | 20 (23.3) |

| Diabetes (%) | 8 ( 9.3) |

| Substance use (%) | 4 ( 4.7) |

| AED Administration | |

| Any AED (%) | 55 (64.0) |

| Levetiracetam (%) | 19 (22.1) |

| Lamotrigine (%) | 19 (22.1) |

| Clonazepam (%) | 14 (16.3) |

| Gabapentin (%) | 16 (18.6) |

| Lorazepam (%) | 9 (10.5) |

| Other (%) | 10 (11.6) |

Table 2:

Sleep measures (total recording time, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep stages). Sleep Stage Totals refer to average percent of time spent in each sleep stage across patients, while Patient Sleep Stages refers to the average percent of time each individual spent in each sleep stage. Artifact is defined as 30-second segments containing two or more seconds of saturated signal (amplitude greater than 500μV), or five or more seconds of flat EEG signal (standard deviation of the amplitude less than .2 μV for five seconds, or less than 1 μV for the whole 30-second segment).

| Sleep Summary | |

| Total Recording Time (hrs) | 5472 |

| Total Sleep Time (hrs) | 3984 |

| Sleep Efficiency | 0.73 |

| n epochs (mean (SD)) | 5.6 (3.4) |

| Epoch length (mean (SD)) | 11.4 (1.5) |

| Sleep Stage Totals (hrs (%)) | |

| N1 | 599 (10.9) |

| N2 | 2,307 (42.2) |

| N3 | 101 (1.8) |

| REM | 978 (17.9) |

| Eye-closed Awake | 544 (9.9) |

| Eye-open Awake (excluded) | 492 (9.0%) |

| Artifact (excluded) | 453 (8.3%) |

| Patient Sleep Stage (hrs (%)) | |

| N1 | 1.2 (11.0) |

| N2 | 4.7 (41.8) |

| N3 | 0.2 (1.9) |

| REM | 2.1 (18.4) |

| Eyes-closed awake | 1.1 (9.7) |

| Eye-open Awake (excluded) | 1.0 (9.0) |

| Artifact (excluded) | .93 (8.3) |

Of our patient cohort, 65% (n =56) was female, 73% (n =63) had a diagnosis of epilepsy and 61% (n =52) used anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) during the EMU stay (Table 1). The cohort had a mean of 5.6 epochs of data per patient (SD=3.4), a mean CA of 42.0 (SD=13.8), and a mean BAI of 9.5 (SD=9.5). The mean BAI of our patient cohort is significantly different from the mean BAI of the MGH training dataset (mean=−.015 years) by approximately 7.6–11.6 years (95% CI). Total recording time was 5,472 hours, with a sleep efficiency of 0.73 (Table 2).

Although average BAI for epileptic patients (BAI=10.2, n=63) was higher than for non-epileptic patients (BAI=7.6, n=23) in our cohort, this difference was not statistically significant (p value = 0.13, t = 1.13, n one-sided two-sample t-test).

A previous study showed that life expectancy decreases by 0.85 years for every increase in standard deviation of BAI (between-patient SD = 9.5). Thus, an average BAI of 9.5 years overall (10.2 years for epileptic patients) may be indicative of a worsened condition overall and specifically in epileptic patients. While we suspect there is a significant difference in BAI between epileptic and non-epileptic patients, the minimum sample size needed to detect a difference of 2.6 years between two samples is 209 patients.

3.2. Brain Age

Figure 5 shows two BA estimates for two different patients. Patient 1 (2A and B) has similar BA estimates for both nights, while patient 2 (2C and D) has different BA estimates for multiple nights. Some aspects of night-to-night variability in sleep patterns can be seen in the EEG spectrogram shown in this figure.

Figure 5-.

Example patient epochs and calculated brain ages (BAs) for two patients. Patient 1 (left) has a stable BA estimate across two nights. Patient 2 (right) has two different BA estimates, with regions of increased delta power associated with a younger BA. Each subplot is a power spectrum for the patient for brain waves of frequency 0–60. Dark blue indicates low power, while red indicates high power.

The average BA in the patient cohort was 51.5 years (SD=10.6 years). Correlation between CA and BA was .73, and correlation between CA and BAI was −.8 before bias correction, and −.64 after. The Kruskal Wallace test comparing SD in patient BAI found no significant differences in SD between any of the six age groups (p-value=.087). A table of patient BAI and SD in patient BAI for all patients is provided in the Supplemental Material (Table S1).

After calculating the relative feature effect sizes as described in methods, features in N3 sleep associated with delta or theta waves accounted for 85% of the observed increase in BAI.

3.3. Effect of Differing Blink Thresholds for Classifying eye-open awake data on BAI Variability

When using blink thresholds of 3, 6 and 9 for each 30-second segment, the standard deviation in patient BAI was 7.0, 7.5 and 7.2 years respectively (without averaging, or n=1). When averaged over two nights (n=2) the standard deviation was 4.5, 4.8 and 4.7 years respectively; 3.44, 3.69 and 3.66 years when n =3; and 2.8, 3.0 and 3.1 years when n=4.

3.4. Night-to-Night Variability

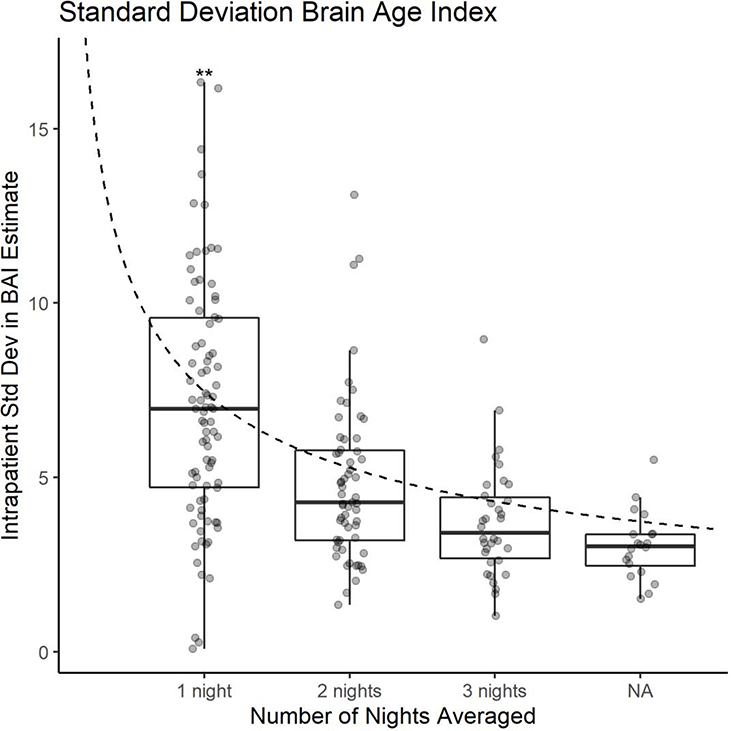

The estimated within-patient night-to-night standard deviation in BAI was 7.5 years. Estimates of BAI derived by averaging over 2, 3, and 4 nights, had lower estimated standard deviations of 4.7, 3.7, and 3.0 years, respectively. The standard error of the average of n BAI estimates approximately decreases according to as n increases, as shown in Figure 6, in support of our “signal + noise” model of BAI night-to-night variability.

Figure 6-.

Average standard deviation in Brain Age Index (BAI) for all patients when samples of sizes 1, 2, 3, and 4 nights are taken respectively. X axis: number of nights averaged, or n. The dashed line represents the decrease in standard error we would expect with increasing sample size . ** represents two outliers with BAI = 20 and 30 respectively.

3.5. Effect of Sleep Stage Distribution on BAI Variability

The Random Forests model describing the relationship between sleep stage distribution for each night and BAI variability generalized poorly to the test dataset, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of .3 (t = .37, p value = .71). Feature importances were not explored due to this lack of a generalizable relationship.

3.6. Analysis of First Night Effect on BAI Variability

When BAI estimates were not averaged (n= 1), the standard deviation in BAI decreased from 7.4 to 7.1 when the first night was removed (difference = −.3). When averaged across 2,3, and 4 nights, BAI changed by −.04, .1 and .1 years respectively after removing the first night. A full list of standard deviations is provided in Supplementary Table S2. Additionally, average patient sleep efficiency between the first night and all other nights was comparable (85.1% for the first night and 84.8% for all other nights).

3.7. Brain Age Risk Lookup Table

The results showing the probability that a patient’s actual BAI is equal to y given that their estimated BAI is x are shown in the probability density tables of Figure 3. When n = 1, we see that the probability distribution is relatively flat and diffuse, reflecting relatively high night-to-night variability of BAI measurements for a single individual from a single night of sleep. By contrast, for a patient whose BAI is averaged over four nights, the probability that the true BAI is equal to their estimated BAI (within 0.5 years) is 12.9%, and further calculations show that there is a 50% probability that a patient’s average BAI estimate from four nights is within 2.0 years of their actual BAI. We also see that the post-measurement probability distribution becomes decidedly more concentrated around the estimated value, reflecting the higher signal-to-noise ratio of multi-night BAI estimates.

The brain age risk lookup tables are also shown in Figure 4. These are similar to the probability density tables, except that probabilities shown are the likelihood that a patient’s true BAI is greater than or equal to y given an estimated BAI of x. Since increased BAI is viewed as concerning for the presence of pathology, this table can be used to calculate a patient’s risk of having an abnormally high BAI.

The blue boxed value in Figure 4c can be interpreted as follows: A typical patient with an estimated BAI of 8 years when averaging three nights of BAI estimates has a 91% chance that their true BAI is greater than or equal to 3 years. Other values can be interpreted similarly.

3.8. Probability of Increased BAI for Individuals in Our Patient Cohort

Our analysis found that 42 patients (49%) had a 95% or higher probability of BAI greater than or equal to 4 years (48% of non-epileptic patients and 49% of epileptic patients). 18 patients (21%) had 95% probability that their true BAI was greater than 9.5 years (9% of non-epileptic patients and 25% of epileptic patients). A list of individual BAI values and the probability of increased BAI is found in Supplementary Table S1.

4. Discussion

Building on the idea that BAI may serve as an accessible biomarker of brain aging, our study quantifies the accuracy of BAI estimates at the individual level, thus providing guidelines for eventually employing such estimates in patient care or clinical trials. We find that the average standard deviation in BAI within individual patients (SD) is approximately 7.5 years. Moreover, a simple “signal+noise” model provides a good description of the data, with night-to-night variability predictably decreasing as as the number of available overnight sleep EEG measurements increases. In particular, averaging over four consecutive nights (or four nights within a few days of each other) reduces noise in BAI estimates by more than half, to 3.0 years. Using at-home sleep monitoring devices, such multi-day sleep measurements are increasingly practical. Thus, these findings bring BAI one step closer to being useable as a measure of brain health in individual patients, whereas previous work has shown results applicable only at the population level. We also believe that it may be possible to increase the signal to noise ratio of any single BAI value by calculating separate BAI estimates for different segments of the night and averaging these, and this remains an area for future investigation.

Additionally, we found that the night-to-night variability in BAI when averaged over four nights changed by .2 years when the blink detection threshold was changed to either 3 or 9 blinks per 30-seconds. This suggests that our blink threshold of 6 blinks per 30 seconds, while not a perfect method of quantifying physical activity, is acceptable for data removal within our patient cohort.

Our estimate of SD = 7.5 years for night-to-night BAI variability within individual patients is close to the average standard deviation between patients found in a previous brain age study among healthy subjects (SD = 8.5 years) (Sun et al. 2019). These results suggest that in a healthy population (mean BAI of 0), much of the interpatient variability is simply due to night-to-night variability in sleep microstructure. There is such variability in sleep macrostructure, and thus, will likely reflect in microstructure variations.

While not the focus of this manuscript, the fact that the patients in our cohort indeed have elevated BAI after correcting for age bias is interesting and, as our results suggest, probably clinically significant. Furthermore, a two-sample t-test comparing mean BAI in our study to the mean BAI in the MGH training dataset confirmed that our cohort has a significantly higher BAI. This elevated BAI has several potential causes, including (1) a high prevalence of epilepsy in our cohort, (2) effects of anti-seizure medications (61% of our cohort received AED drugs), or (3) sleep in the EMU is often intentionally disturbed in order to provoke seizures, which likely results in poor sleep quality. An association of elevated BAI with epilepsy would be in agreement with recent studies showing that MRI-based BAI is higher in patients with chronic epilepsy (Pardoe et al. 2017, Sone et al. 2019). The fact that no significant difference in BAI was found within our cohort between epileptic vs non-epileptic perhaps makes this less likely, however our study was not specifically powered for this comparison (a power analysis suggests that the minimum sample size required to detect a difference in mean BAI of 2.6 between two groups where SD=9.6 is 209 patients). Epilepsy is associated with reduced life expectancy, and a recent study found that an increase of 1 standard deviation in BAI (9.5 years in our cohort), is associated with a 0.85-year decrease in lifespan on a population level (Paixao et al. 2020). A mean BAI of 9.5 years in a cohort of epileptic patients is thus biologically plausible.

Although our data do not allow us to say definitively which of these possible explanations is correct, we feel that sleep disruption likely accounts for the majority of the effect. We found that 85% of the increase in BAI in our cohort as compared to the training dataset of healthy normal patients is accounted for by parameters related to delta and theta-wave activity during N3 sleep, suggesting that disrupted sleep may also impact the observed increase in BAI. From a signal-to-noise perspective, we believe that short-term sleep disturbances (such as those found in the EMU) act as noise, decreasing the accuracy of the patient’s actual BA estimate without changing the BA itself.

In exploring whether individual patients have abnormal BAI, our analysis found that 48% of non-epileptic patients and 49% of epileptic patients had a BAI of greater than or equal to 4 years (with 95% confidence), while 9% of non-epileptic patients and 25% of epileptic patients had a BAI of greater than or equal to 9.5 years (with 95% confidence). The fact that a difference between epileptic and non-epileptic patients is only evident with a BAI threshold of 9.5 years is likely due to the high BAI in our patient cohort overall as explained above.

In general, night-to-night stability of the BAI is in keeping with other estimates of night-to-night variability/stability of sleep physiology. These include EEG patterns using high-density EEG (Massimini et al. 2004), sleep EEG data from twins (Hori 1986; Gorgoni et al. 2019), heart rate response to arousal from sleep (Gao et al. 2017), performance deficits following sleep deprivation (Kuna et al. 2012), and sleep stability assessed by cardiopulmonary coupling (Thomas et al. 2018). These studies did not use clinically abnormal patient groups.

Our present results provide guidance for how to interpret BAI values measured for an individual in light of prior population studies. Sun et al. previously showed the population-level difference between patients with diabetes and those without is 3.5 years, and patients with neurological disorders had a BAI that was an average of 4.0 years higher than that of healthy control patients (Sun et al. 2019). Combined with our current results, we see that an individual with a four-night (average) BAI of 8 years or greater has a 95% chance that their true BAI is at least 4, raising the probability that this patient indeed has underlying brain pathology. This information may serve as a warning signal of the possible presence of neurodegenerative disease or other chronic diseases that may have secondary effects on brain function, warranting further investigation or monitoring. While algorithm stability does not change significantly with age (as confirmed by Kruskal Wallace testing), clinical interpretation of excess BAI values may vary based on patient age. This occurs because of an inverse relationship between BAI and age (BAI decreases with age), as evidenced by a correlation of −.6. This bias is due to the natural limits of aging and is found in MRI-based brain age calculations as well (Beheshti et al. 2019).

There are several limitations in our study. (1) Our cohort is comprised of EMU patients. While EEG epochs with epileptiform activity were excluded from the study, many of our patient cohort had a clinical diagnosis of epilepsy. Furthermore, out-of-home sleep is typically thought to be disrupted, particularly during the first night. While sleep efficiency is a crude approximation of sleep quality, average patient sleep efficiency on the first night was actually slightly higher than average patient sleep efficiency over all other nights, suggesting that quality of sleep did not improve significantly over the EMU stay. Therefore, this patient cohort does not represent the general patient population. However, our analysis of the first-night effect shows that removing first-night BAI estimates decreases the standard deviation by at most .3 years, which suggests that the BAI algorithm is not affected largely by the first-night effect in our dataset. (2) Our analysis assumes a uniform pre-test probability distribution (prior distribution) for the BAI. However, since the BA distribution is unknown population-wide, this assumption seems reasonable, as it avoids assuming healthy or sick BAI values. This assumption also supports the overarching goal of the algorithm as a reasonably accurate biomarker for any patient, whether healthy or sick, without assuming the patient’s state beforehand. Nevertheless, future research should investigate whether it is useful to create more specific pretest probability distributions for specific populations, e.g., based on gender, race, medical symptoms, or other clinical characteristics. (3) Sleep staging was performed algorithmically as opposed to being hand-labeled by experts. However, this may be argued as a strength, since it reduces between-expert variation in sleep staging as an additional potential source of variation. (4) 61% of patients received antiepileptic drugs during their stay at the EMU which may have affected the EEG signal and consequently the BAI calculation. Of patients receiving AEDs, 71% were diagnosed with epilepsy, thus a combination of AED infusion and epilepsy may have affected BAI calculation. It could be anticipated that in an average population, the BAI stability may be greater, though this hypothesis needs to be tested based on recording multiple nights of sleep EEG. (5) This metric requires multiple nights of data to provide a stable BAI estimate on an individual level, which is not practical in a conventional sleep laboratory. However, BAI estimates are intended to be taken in a patients’ home, which may be facilitated by recent developments in take-home EEG technology (Wyckoff et al. 2015; Neumann et al. 2018; Yohanandan et al. 2018). (6) The ELM algorithm is intended to be applied to sleep EEG data, thus, it does not apply to other types of EEG data, including physical activity and epileptiform activity (for which the sleep stage is undefined). This necessitates that EEGs be screened by clinical experts before this algorithm is applied. However, our results show that the BAI algorithm can be applied to patients with epilepsy as long as EEG epochs are free of epileptiform activity. Furthermore, most subjects who might benefit from the information the algorithm can provide do not have epilepsy. (7) The threshold used for blink detection and data removal was tuned to our dataset and should be further optimized and validated on external datasets. (8) The BAI algorithm is relatively simple, based on a linear model. It is possible that more sophisticated algorithms (e.g. deep learning models) could produce estimates of BAI that have lower night-to-night variability, in which case fewer nights of averaging would be needed to obtain a stable estimate. (9) At-home sleep measurement faces two challenges: proper EEG set-up, and whether the quality of sleep will be sufficiently free of artifacts. While there are technical difficulties with setting up the EEG at home, limiting set up to very few electrodes (six plus a reference), as is done in most home sleep EEG systems, helps mitigate this difficulty. Since the patients would be instructed to apply electrodes only immediately prior to and during sleep, Fp1 and Fp2 channels used in the present study would not be necessary to remove active, awake segments (Fp1 and Fp2 were not used in the original study estimating BA) (Sun et al. 2019). Furthermore, we believe that at-home EEG recordings would facilitate higher sleep quality than in the EMU, where sleep deprivation is often intentionally disrupted for clinical purposes (i.e. to provoke epileptic seizures). Nevertheless, further studies examining at-home application of the BA algorithm are needed to determine how well BAI can be measured with existing home EEG devices.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, averaging BAs calculated from multiple nights reduces the effect of night-to-night variability, providing a biomarker of brain health interpretable at the level of an individual. We have provided figures that can serve as clinical guides in applying EEG-based BA as a biomarker of brain aging.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Using multiple nights of EEG to estimate the night-to-night variability of a previously established sleep EEG-based Brain Age Index (BAI).

Averaging BAI over n nights reduces night-to-night variability of BAI by a factor of .

Average BAI over multiple nights is a relatively stable estimate of brain health.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted while Dr. Westover was a Breakthroughs in Gerontology Grant recipient, supported by the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research and the American Federation for Aging Research; by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine through an AASM Foundation Strategic Research Award; and by grants from the NIH (1R01NS102190, 1R01NS102574, 1R01NS107291, 1RF1AG064312).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Thomas declares the following conflicts: 1) Patent and license for a technology using ECG to assess sleep quality and sleep apnea, licensed to MyCardio, LLC; 2) Patent and license for an auto-CPAP algorithm, licensed to DeVilbiss-Drive. 3) Unlicensed [patent to treat central sleep apnea with low concentration CO2 with positive airway pressure. 4) Consultant to Jazz Pharmaceuticals; 5) General sleep medicine consulting for GLG Councils and Guidepoint Global.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al Zoubi O, Ki Wong C, Kuplicki RT, Yeh H, Mayeli A, Refai H, et al. Predicting Age From Brain EEG Signals—A Machine Learning Approach. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:184 Available from: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beheshti I, Nugent S, Potvin O, Duchesne S. Bias-adjustment in neuroimaging-based brain age frameworks: A robust scheme. NeuroImage Clin. 2019;24:102063 Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31795063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner DP, Dijk DJ, Borbely AA. Repeated partial sleep deprivation progressively changes the EEG during sleep and wakefulness. Sleep. 1993;16:100–13. Available from: 10.1093/sleep/16.2.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carne RP, Vogrin S, Litewka L, Cook MJ. Cerebral cortex: An MRI-based study of volume and variance with age and sex. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:60–72. Available from: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier J, Land S, Buysse DJ, Kupfer DJ, Monk TH. The effects of age and gender on sleep EEG power spectral density in the middle years of life (ages 20–60 years old). Psychophysiology. 2001;38(2):232–42. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11347869 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danker-Hopfe H, Anderer P, Zeitlhofer J, Boeck M, Dorn H, Gruber G, et al. Interrater reliability for sleep scoring according to the Rechtschaffen & Kales and the new AASM standard. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:74–84. Available from: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00700.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange AG, Cole JH. Commentary: Correction procedures in brain-age prediction. NeuroImage Clin. 2020;26:102229 Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32120292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Azarbarzin A, Keenan BT, Ostrowski M, Pack FM, Staley B, et al. Heritability of heart rate response to arousals in twins. Sleep. 2017;40:74–84. Available from: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00700.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgoni M, Reda F, D’Atri A, Scarpelli S, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. The heritability of the human K-complex: A twin study. Sleep. 2019;42:zsz053 Available from: 10.1093/sleep/zsz053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramfort A, Luessi M, Larson E, Engemann DA, Strohmeier D, Brodbeck C, et al. MEG and EEG data analysis with MNE-Python. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:267 Available from: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramfort A, Luessi M, Larson E, Engemann DA, Strohmeier D, Brodbeck C, et al. MNE software for processing MEG and EEG data. Neuroimage. 2014;86:446–60. Available from: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori A Sleep Characteristics in Twins. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1986;40:35–46. Available from: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1986.tb01610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuna ST, Maislin G, Pack FM, Staley B, Hachadoorian R, Coccaro EF, et al. Heritability of Performance Deficit Accumulation During Acute Sleep Deprivation in Twins. Sleep. 2012;35:1223–1233. Available from: 10.5665/sleep.2074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson E mne-python/eog.py · mne-tools/mne-python · GitHub. 2019a;. Available from: https://github.com/mne-tools/mne-python/blob/maint/0.19/mne/preprocessing/eog.py#L89

- Larson E mne-tools/mne-python · GitHub. 2019b;. Available from: https://github.com/mne-tools/mnepython/blob/maint/0.19/mne/preprocessing/_peak_finder.py#L14

- Lepage KQ, Kramer MA, Chu CJ. A statistically robust EEG re-referencing procedure to mitigate reference effect. J Neurosci Methods. 2014;235:101–16. Available from: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD. Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Magalang UJ, Chen N-H, Cistulli PA, Fedson AC, Gíslason T, Hillman D, et al. Agreement in the Scoring of Respiratory Events and Sleep Among International Sleep Centers. Sleep. 2013;36:591–6. Available from: 10.5665/sleep.2552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimini M, Huber R, Ferrarelli F, Hill S, Tononi G. The sleep slow oscillation as a traveling wave. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6862–70. Available from: 10.1523/jneurosci.1318-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann T, Baum AK, Baum U, Deike R, Feistner H, Hinrichs H, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic yield of a patient-controlled portable EEG device with dry electrodes for home-monitoring neurological outpatients—rationale and protocol of the HOMEONE pilot study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4:100 Available from: 10.1186/s40814-018-0296-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paixao L, Sikka P, Sun H, Jain A, Hogan J, Thomas R, et al. Excess brain age in the sleep electroencephalogram predicts reduced life expectancy. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;88:150–5. Available from: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardoe HR, Cole JH, Blackmon K, Thesen T, Kuzniecky R. Structural brain changes in medically refractory focal epilepsy resemble premature brain aging. Epilepsy Res. 2017;133:28–32. Available from: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone D, Beheshti I, Maikusa N, Ota M, Kimura Y, Sato N, et al. Neuroimaging-based brain-age prediction in diverse forms of epilepsy: a signature of psychosis and beyond. Mol Psychiatry. 2019; Available from: 10.1038/s41380-019-0446-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Jia J, Goparaju B, Bin Huang G, Sourina O, Bianchi MT, et al. Large-scale automated sleep staging. Sleep. 2017;40:zsx139 Available from: 10.1093/sleep/zsx139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Paixao L, Oliva JT, Goparaju B, Carvalho DZ, van Leeuwen KG, et al. Brain age from the electroencephalogram of sleep. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;74:112–20. Available from: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas RJ, Wood C, Bianchi MT. Cardiopulmonary coupling spectrogram as an ambulatory clinical biomarker of sleep stability and quality in health, sleep apnea, and insomnia. Sleep. 2018;41:zsx196 Available from: 10.1093/sleep/zsx196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urakami Y, A. A, K. G. Sleep Spindles – As a Biomarker of Brain Function and Plasticity. In: Advances in Clinical Neurophysiology. InTech; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff SN, Sherlin LH, Ford NL, Dalke D. Validation of a wireless dry electrode system for electroencephalography. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2015;12:95 Available from: 10.1186/s12984-015-0089-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Ge Y, Lu H. Noninvasive quantification of whole-brain cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO 2 ) by MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:141–8. Available from: 10.1002/mrm.21994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohanandan SAC, Kiral-Kornek I, Tang J, Mshford BS, Asif U, Harrer S. A Robust Low-Cost EEG Motor Imagery-Based Brain-Computer Interface. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; 2018. p. 5089–92. Available from: 10.1109/embc.2018.8513429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.