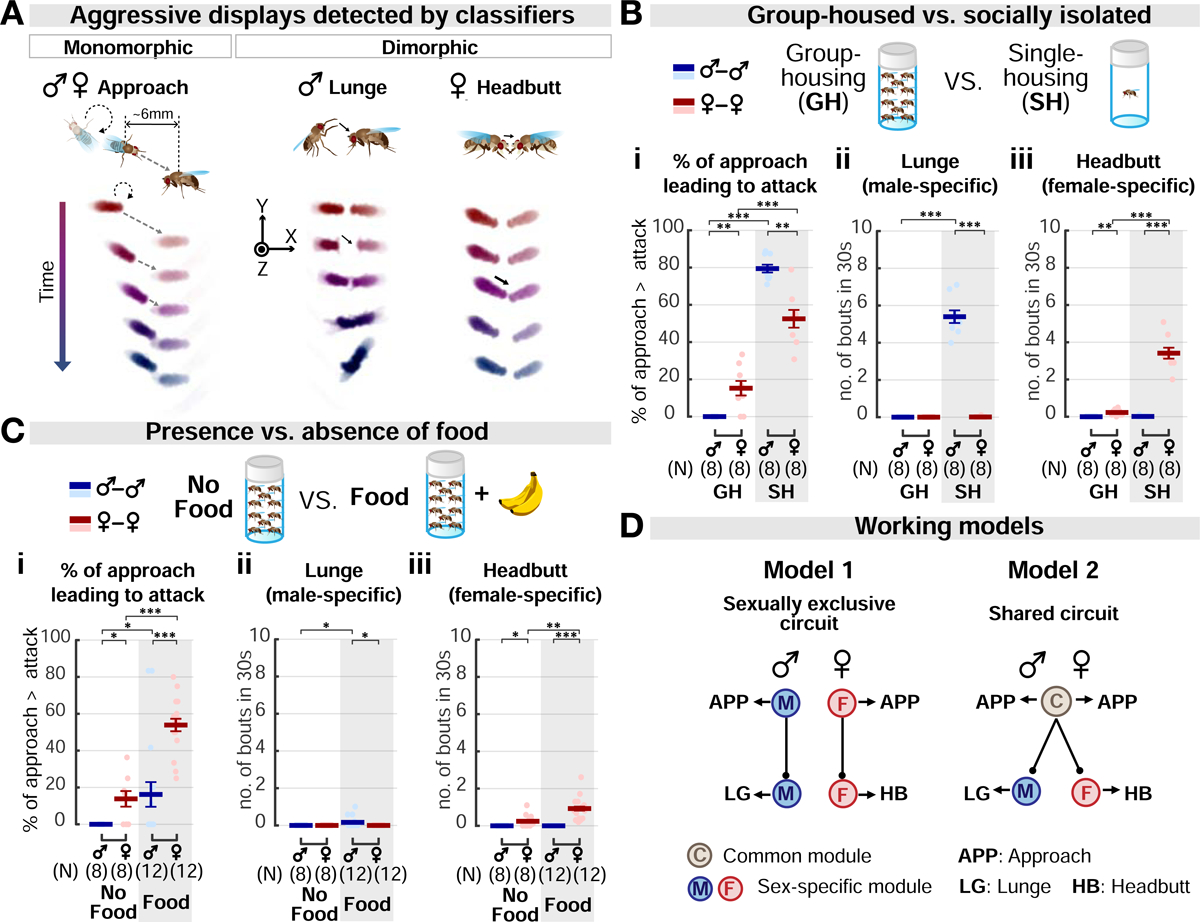

Figure 1. Contextual influences on sexually monomorphic and dimorphic aggressive actions in males and females.

(A) Example bouts detected by automated behavioral classifiers. Approach: fly orients and moves towards target. Lunge: fly raises its upper body and slams down onto target. Headbutt: fly thrusts its body towards the target and strikes it with its head. See also Figure S1.

(B-C) Effects of social isolation (B) and food presence (C) on male vs. female aggression. (B) Testers were reared either in groups (GH; 20 flies/vial) or in isolation (SH; 1 fly/vial) for 6 days prior to test. In (C), a banana chunk (“Food”) was provided during testing of GH flies. Dark lines: mean±SEM. Light circles: individual data. Here and throughout, ns, not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; and ***p<0.001. Full genotypes of experimental flies for this and subsequent figures are listed in Table S1. Statistical data are listed in Table S3.

(D) Proposed models for aggression circuitry in males and females. Model 1, the aggression circuit in each sex is composed exclusively of sex-specific components. Model 2, some aggression circuit components, controlling similar behaviors, are shared by both sexes.