Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infection caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which has resulted in a global pandemic with significant morbidity and mortality. This illness has been associated with numerous dermatologic manifestations, including morbilliform rash, urticaria, and retiform purpura.1 Additionally, pressure ulcers are a concerning comorbidity for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 due to impaired perfusion and reduced mobility in patients with compromised respiratory function.2 Placing patients with severe respiratory disease due to COVID-19 in a prone position has improved outcomes3 but has also been associated with the development of pressure ulcers.4 Other risk factors for developing pressure ulcers include intensive care unit (ICU) stay, fever, incontinence, and poor nutrition with loss of protective body mass.5,6

Purpuric lesions may represent the proposed coagulopathy and microvascular injury of COVID-19, and the pathophysiology is unclear.7 This case series reports on purpuric pressure ulcers, a novel cutaneous finding of pressure-related injury with secondary hemorrhage in patients with COVID-19. The morphology, clinical course, and histopathological features of this cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 are described to investigate its etiology.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of 11 patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 at a tertiary care medical institution between March and May 2020 was performed. These patients developed purpuric lesions, for which dermatology was consulted for evaluation and management. A small subset of patients underwent skin biopsy to clarify diagnosis and exclude thrombotic processes.

For histopathology staining, SARS-CoV-2 single-color RNA in-situ hybridization was performed using RNAscope 2.5 LS Probe-V-nCoV2019-S Cat No. 848568 and RNAscope 2.5 LS Reagent Kit-RED Cat No. 322150 Advanced Cell Diagnostic on automated BondRx platform (Leica Biosystems). 5-μm thick sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsy tissue were used. All of the steps from baking for one hour at 60°C to counterstain with hematoxylin were performed on the BondRx machine. RNA unmarking was carried out using Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 for 15 min at 95°C followed by protease treatment for 15 min and probe hybridization for 2 h. The signal was amplified by a series of amplification steps followed by color development in red using Bond Polymer Refine Red Detection in the forms of red dots.

Results

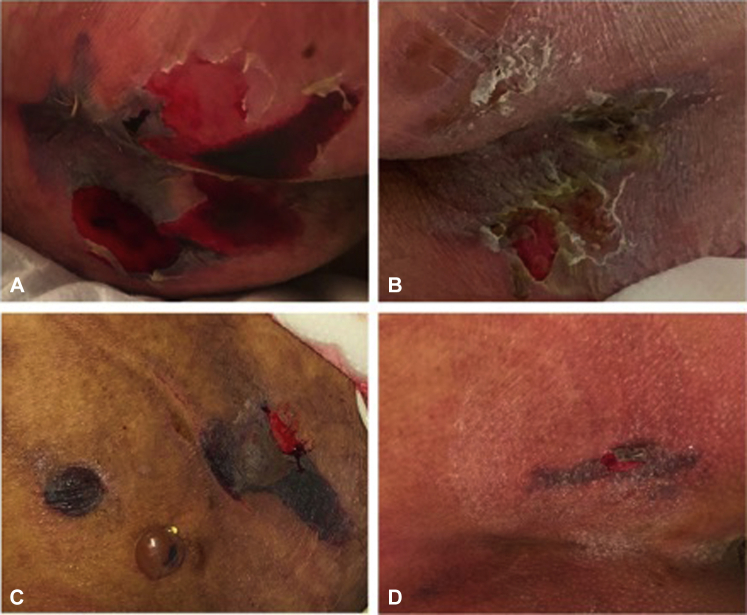

Patient demographic and clinical features are summarized in Table 1. The mean patient age was 56.3 years, and the mean length of hospitalization was 44.7 days. The most common medical comorbidities were obesity (72.7%), urinary (36.4%) and fecal incontinence (27.3%), and diabetes (27.3%). All patients were critically ill and admitted to the ICU, and there were three deaths (27.3%) from COVID-19 infection. Most of the cohort (90.9%) developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and primary teams reported that standard repositioning was limited by tenuous respiratory status for many patients. Patients were noted to have purpuric lesions at pressure-dependent sites, often with geometric borders and sometimes with associated bullae, which typically progressed to central ulceration with eschar (Fig 1). Based on the morphology of these lesions, such as some with retiform appearance, the initial differential diagnosis included coagulopathies, vasculitides, and pressure-induced injuries. The mean time to onset of skin lesions was 10 days (standard deviation [SD], 5.4 days) from admission. These purpuric pressure ulcers were observed most frequently at the buttocks (63.6%) and at other pressure-dependent sites such as the face (27.3%) in prone patients. The average D-dimer and fibrinogen levels were elevated, and prothrombin time (PT) was mildly elevated, while partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and platelet count values remained within normal range.

Table 1.

Summary of patient presentation and clinical course.

| Patient characteristic | Total (n = 11) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 56.3 ± 12.0 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 4 |

| Male | 7 |

| Race | |

| White | 6 |

| Other | 2 |

| Unknown | 3 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 5 |

| Not Hispanic | 2 |

| Unknown | 4 |

| Hospitalization Characteristics | |

| Length of stay in days (mean ± SD) | 44.7 ± 23.8 |

| Days to onset of skin lesions (mean ± SD) | 10.0 ± 5.4 |

| ICU-level care | 11 |

| Death | 3 |

| Skin Lesion Location | |

| Head, face, and neck | 3 |

| Upper extremity | 1 |

| Lower extremity | 1 |

| Buttocks/sacrum | 7 |

| Trunk | 2 |

| Multiple locations | 2 |

| Past Medical History | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 |

| Cognitive impairment | 3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 |

| Incontinence | |

| Fecal | 3 |

| Urinary | 4 |

| Obesity | |

| Class I (BMI 30.0-34.9) | 4 |

| Class II (BMI 35.0-39.9) | 1 |

| Class III (BMI >40.0) | 3 |

| Osteoporosis | 1 |

| Clinical Course, Events, and Treatments | |

| Anemia | 11 |

| Fever | 11 |

| Lower extremity edema | 2 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 2 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 4 |

| Malnutrition | 8 |

| Minimum albumin, (mean ± SD) | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| Feeding tube | 11 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 1 |

| Rectal intubation | 11 |

| Tracheal intubation | 11 |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation | 9 |

| Urinary catheterization | 9 |

| Coagulopathy at Lesion Onset (mean ± SD) | |

| PT [10-13 s] | 14.8 ± 1.0 |

| PTT [25-40 s] | 38.2 ± 10.5 |

| Platelet count [150–350 thousand cells/mm3] | 321 ± 123 |

| D-dimer [<500 ng/mL] | 3410 ± 1390 |

| Fibrinogen [200 to 400 mg/dL] | 691 ± 132 |

BMI, Body mass index; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; SD, standard deviation.

Fig 1.

Photographs of purpuric buttock lesions. A, Well-demarcated purpuric patches with focal areas of skin sloughing on the buttocks in patient #1 recorded 6 days after lesion onset. B, A well-demarcated purpuric patch with focal full-thickness epidermal loss on the buttocks of patient #2 observed 10 days after lesion onset. C, Three areas of well-demarcated purpura with overlying bulla formation on the buttocks of patient #3 observed 6 days after lesion onset. D, Well-demarcated areas of purpura with focus of denuded skin on the buttocks of patient #9 recorded 5 days after lesion onset.

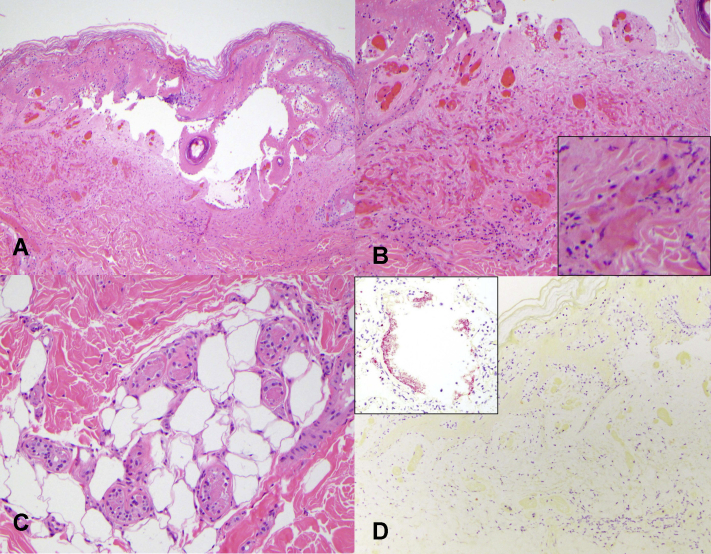

Given limited access to personal protective equipment at the time and the consistency of the lesion morphology across patients, four skin biopsies were obtained from three patients with clinical purpuric pressure injuries on the buttocks (Table 2). All biopsies demonstrated epidermal and eccrine gland necrosis and fibrin thrombi within superficial, but not deep, dermal blood vessels. Given the appearance of these lesions at pressure-dependent sites and the absence of clear laboratory evidence of frank thrombotic or coagulopathic disorders such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, these histologic findings were supportive of pressure-induced necrosis in clinical context (Fig 2, A-C). SARS-CoV-2 RNA in-situ hybridization performed on all four skin biopsies was negative (Fig 2, D). Clinical and laboratory characteristics were not significantly different for biopsied patients compared with those of others (P > .05).

Table 2.

Patient clinical course and skin findings

| Patient presentation | Complications | Skin finding | Biopsy results | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1| 54M with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type II diabetes mellitus presenting with 8 days of fever, cough, malaise, dyspnea, anorexia | ICU, ARDS, septic shock, pulmonary embolism | Purpuric pressure injury on buttocks, 15 days after admission | Epidermal necrosis and fibrin thrombi within superficial dermal blood vessels and eccrine gland necrosis: pressure injury | 4 weeks of ventilation, wound care, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, atorvastatin | Discharged to long-term care facility 5 weeks after admission |

| #2| 76M with hyperlipidemia presenting with 2 weeks of malaise, dyspnea | ICU, ARDS, acute renal failure | Purpuric pressure injury on buttocks, 8 days after admission | Epidermal necrosis, fibrin thrombi within superficial dermal blood vessels and eccrine gland necrosis: pressure injury | 2 weeks of ventilation, wound care, azithromycin hydroxychloroquine | Discharged to long-term care facility 6 weeks after admission |

| #3| 72F with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cirrhosis presenting with 2 weeks of fever, cough | ICU, ARDS, pneumonia, candidemia | Purpuric pressure injury on buttocks, 11 days after admission | Both sites showing epidermal necrosis and subcutaneous fat necrosis: pressure injury | 3 weeks of ventilation, wound care, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, trial of nitric oxide | Discharged to long-term care facility 5 weeks after admission |

| #4| 57F with COPD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia presenting with 6 days of sore throat, ear discomfort, fever | ICU, ARDS, sepsis, renal failure | Purpuric pressure injury on face, breast, abdomen, and right wrist, 5 days after admission | - | 3 weeks of ventilation, wound care, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine | Discharged to long-term care facility 4 weeks after admission |

| #5| 64M with type II diabetes mellitus, myasthenia gravis presenting with 4 days of fever, cough | ICU, ARDS, thrombocytopenia, GI bleed, sepsis, myocardial infarction | Purpuric pressure injury on buttocks and face, 16 days after admission | - | 5 weeks of ventilation, wound care, hydroxychloroquine | Deceased 5 weeks after admission |

| #6| 58M with hypertension, alcohol use disorder presenting with 2 weeks of dyspnea | ICU, ARDS, acute kidney injury, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, cerebrovascular accident, shock | Purpuric pressure injury on back, 7 days after admission | - | 1 week of ventilation, wound care | Deceased 1 week after admission |

| #7| 39F with asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, type II diabetes mellitus presenting with 9 days of cough, dyspnea, malaise | ICU, ARDS, pulmonary embolism, GI bleed, pneumonia, urinary tract infection | Purpuric pressure injury on buttocks and left breast, 30 days after admission | - | 7 weeks of ventilation, wound care | Transferred to outside hospital ICU 7 weeks after admission |

| #8| 65M with asthma presenting with 1 week of fever, cough, dyspnea | ICU, ARDS, deep vein thrombosis, acalculous cholecystitis, sepsis | Purpuric pressure injury on neck, bilateral arms, and left leg, 18 days after admission | - | 4 weeks of ventilation, wound care, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine | Deceased 4 weeks after admission |

| #9| 54F with hypertension, seizures, migraines, thyroid disease presenting with 2 weeks of dyspnea, sore throat, myalgia, nausea, headache | ICU, ARDS, sinus tachycardia, cardiomyopathy | Purpuric pressure injury on buttocks, 17 days after admission | - | 5 weeks of ventilation, wound care, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine | Discharged to long-term care facility 6 weeks after admission |

| #10| 48M with no PMH presenting with 9 days of fever, cough, lethargy | ICU, ARDS, acute kidney injury, bacteremia | Purpuric pressure injury on right face, bilateral knees, left chest, right hand, posterior head, and under tracheostomy tube, 7 days after admission | - | 7 weeks ventilation, wound care, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine | Discharged to home 10 weeks after admission |

| #11| 34M with hypothyroidism presenting with 1 week of cough, fever, dyspnea | ICU, ARDS, renal failure, liver failure, pulmonary embolism, splenic infarction, liver infarction, bacteremia, fungemia, pancreatitis | Purpuric pressure injury on buttocks, 11 days after admission | - | 14 weeks of ventilation, wound care, surgical debridement, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, remdesivir | Deceased 14 weeks after admission |

ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome; F, female; GI, gastrointestinal; ICU, intensive care unit; M, male.

Fig 2.

Histopathological features of biopsied purpuric skin lesions. A, The epidermis and underlying follicular epithelium exhibited necrosis, resulting in a subepidermal vesiculation (original magnification, ×100). B, Fibrin thrombi and erythrocytes were seen plugging the superficial dermal blood vessels (original magnification, ×200). C, The eccrine coils also exhibited necrosis (original magnification, ×200). D, SARS-CoV-2 RNA in-situ hybridization was negative with the inset showing positive staining in pulmonary control tissue (original magnification, ×200; inset - original magnification, ×400).

Case descriptions of patients undergoing skin biopsy

Case 1—A 54-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type II diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department (ED) with respiratory symptoms and fever for eight days. Shortly after admission, his respiratory status declined prompting rapid intubation. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was positive for SARS-CoV-2, and his initial laboratory abnormalities included elevated creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), D-dimer, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin. 15 days after admission, he developed a purpuric pressure ulcer on the bilateral buttocks, which was biopsied by dermatology and suggestive of pressure injury. His hospital course was complicated by septic shock and pulmonary embolism. The wound improved with topical petrolatum and non-adhesive padded dressing as well as increased mobility after extubation and discharge to a rehabilitation facility. His rehabilitation course was complicated by wound infection requiring antibiotic treatment.

Case 2—A 76-year-old male with a history of hyperlipidemia presented to the ED with two weeks of malaise and dyspnea. The PCR test was positive for SARS-CoV-2, and his initial laboratory abnormalities included elevated LDH, liver function tests (LFTs), and PT. Three days after admission, he was intubated due to worsening respiratory function. Eight days after admission, he developed a purpuric pressure ulcer on his bilateral buttocks that was biopsied by dermatology and suggestive of pressure injury. His hospital course was complicated by acute renal failure. The purpuric pressure ulcer persisted after discharge during his rehabilitation course and was classified as a stage three wound six months after initial development.

Case 3—A 72-year-old female with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cirrhosis presented to the ED with two weeks of fever and cough. The PCR test prior to admission was positive for SARS-CoV-2, and at admission the patient was intubated due to declining respiratory function. Initial laboratory abnormalities showed elevated LDH, LFTs, D-dimer, and ESR. 11 days after admission, she developed purpuric pressure ulcers on the bilateral buttocks that were biopsied by dermatology and suggestive of pressure injury. Her hospital course was complicated by pneumonia and candidemia. The purpuric pressure ulcer persisted despite daily wound care, and patient follow up was not available after being discharged to a long-term care facility.

Discussion

This is a large case series of dermatologist-evaluated purpuric pressure ulcers in patients with COVID-19. In this cohort, these lesions were associated with obesity, impaired mobility in the setting of critical illness, incontinence, and malnutrition. Lab studies were not suggestive of coagulopathies, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation or cryoglobulinemia. Although several patients in this cohort developed thrombotic complications of COVID-19 such as pulmonary embolism (36.4%), deep vein thrombosis (18.2%), and cerebrovascular accident (9%), skin biopsies of dependent purpura and ulcers were supportive of pressure injury rather than thrombotic vasculopathy. Case reports of retiform purpura have demonstrated multiple thrombi occluding small vessels of the deeper dermis in patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.7,8 Differences between these and previously reported findings suggest that purpuric lesions of different etiologies may develop in COVID-19. Our findings suggest that purpuric features of these pressure injuries are less likely indicative of occult pathology resulting from COVID-19 infection and rather likely represent secondary hemorrhage due to superficial cutaneous vessel injury in the setting of prolonged pressure.

Although our understanding of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 and their underlying pathophysiology is still in development, this case series contributes to the limited literature on purpuric lesions in patients with COVID-19. A limitation of this study is the low rate of biopsy acquisition during the initial COVID-19 pandemic peak, which has been commented on in other studies.9 However, purpuric pressure necrosis without thrombotic vasculopathy appears to be a common complication of COVID-19-related hospitalization. These results suggest that measures to prevent pressure injury, such as frequent inspection of the skin for early recognition of concerning lesions, routine repositioning as allowable for offloading of pressure at dependent sites, and prophylactic utilization of pressure-offloading dressings over high-risk areas in susceptible patients, should be implemented meticulously in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19. Further research is needed to determine effective strategies for prevention and management of pressure-related injury in patients with COVID-19 given the significant associated morbidity.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

References

- 1.Freeman E.E., McMahon D.E., Lipoff J.B. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang J., Li B., Gong J., Li W., Yang J. Challenges in the management of critical ill COVID -19 patients with pressure ulcer. Int Wound J. 2020;17(5):1523–1524. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li L., Li R., Wu Z. Therapeutic strategies for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00661-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girard R., Baboi L., Ayzac L., Richard J.C., Guérin C., Proseva Trial Group The impact of patient positioning on pressure ulcers in patients with severe ARDS: results from a multicentre randomised controlled trial on prone positioning. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(3):397–403. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robnett M.K. The incidence of skin breakdown in a surgical intensive care unit. J Nurs Qual Assur. 1986;1(1):77–81. doi: 10.1097/00001786-198611000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mervis J.S., Phillips T.J. Pressure ulcers: pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):881–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magro C., Mulvey J.J., Berlin D. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch-Amate X., Giavedoni P., Podlipnik S. Retiform purpura as a dermatological sign of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) coagulopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):e548–e549. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Q., Fang X., Pang Z., Zhang B., Liu H., Zhang F. COVID-19 and cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(11):2505–2510. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]