Abstract

Objective

To determine the benefits associated with brief inpatient rehabilitation for coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) patients.

Design

Retrospective chart review.

Setting

A newly created specialized rehabilitation unit in a tertiary care medical center.

Participants

Consecutive sample of patients (N=100) with COVID-19 infection admitted to rehabilitation.

Intervention

Inpatient rehabilitation for postacute care COVID-19 patients.

Main Outcome Measures

Measurements at admission and discharge comprised a Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index (including baseline value before COVID-19 infection), time to perform 10 sit-to-stands with associated cardiorespiratory changes, and grip strength (dynamometry). Correlations between these outcomes and the time spent in the intensive care unit (ICU) were explored.

Results

Upon admission to rehabilitation, 66% of the patients were men, the age was 66±22 years, mean delay from symptom onset was 20.4±10.0 days, body mass index was 26.0±5.4 kg/m2, 49% had hypertension, 29% had diabetes, and 26% had more than 50% pulmonary damage on computed tomographic scans. The mean length of rehabilitation stay was 9.8±5.6 days. From admission to discharge, the Barthel index increased from 77.3±26.7 to 88.8±24.5 (P<.001), without recovering baseline values (94.5±16.2; P<.001). There was a 37% improvement in sit-to-stand frequency (0.27±0.16 to 0.37±0.16 Hz; P<.001), a 13% decrease in post-test respiratory rate (30.7±12.6 to 26.6±6.1; P=.03), and a 15% increase in grip strength (18.1±9.2 to 20.9±8.9 kg; P<.001). At both admission and discharge, Barthel score correlated with grip strength (ρ=0.39-0.66; P<.01), which negatively correlated with time spent in the ICU (ρ=–0.57 to –0.49; P<.05).

Conclusions

Inpatient rehabilitation for COVID-19 patients was associated with substantial motor, respiratory, and functional improvement, especially in severe cases, although there remained mild persistent autonomy loss upon discharge. After acute stages, COVID-19, primarily a respiratory disease, might convert into a motor impairment correlated with the time spent in intensive care.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemics, Rehabilitation

List of abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus 2019; CT, computed tomography; ICU, intensive care unit; PT, physical therapy; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

The coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic forced health care systems to rapidly adjust to constantly evolving situations. Traditional acute care units were converted into COVID-19 units with concerns about overwhelming hospital capacities. The rapid development of specific rehabilitation units was essential in response to the high level of dependence observed in many patients and the need to prevent outbreaks in other departments. Several authors have highlighted the need to prepare for postacute care, but few functional outcomes after COVID rehabilitation have been reported.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

COVID-19 rehabilitation not only needs to address cardiorespiratory and motor deconditioning, as seen in acute respiratory distress syndrome, but also neurologic deterioration, aggravation of comorbidities, and consequences of prolonged bed rest.10, 11, 8, 9 In this work, we quantified the changes in functional parameters from admission to discharge for the first 100 patients in a specifically designed COVID-19 rehabilitation unit, comparing non-intensive care unit (ICU) patients with post-ICU patients and those after short vs long prior stay in acute care.

Methods

Creation of the unit and target patients

A unit of 35 single rooms dedicated to COVID rehabilitation was opened to meet the needs of our hospital group during the spring 2020 epidemic wave, with all patients coming from its acute care units. Admission criteria in the rehabilitation unit comprised (1) positive reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or computed tomography (CT) scan supporting COVID-19 infection (because RT-PCR sensitivity has been reported to range from 66% to 80%, patients having highly evocative clinical signs and CT scans were considered as COVID-19 patients, as in acute care departments)12; (2) no oxygen requirement greater than 6 liters per minute (patients requiring >6 L/min of oxygen were deemed unstable and remained under acute care); (3) clinical impression of stability; (4) no current endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy; and (5) need for rehabilitation and/or extensive social work to optimize a return home.

Nursing and medical care

The ward was organized into subunits of 8 to 9 patients, each operated by a team of 2 physicians, 1 nurse, 2 nursing assistants, and 2 physical therapists. Full personal protective equipment were donned by the staff for patients less than 14 days after symptom onset. Patients remained in their room at all times, including for their rehabilitation treatments. Following evidence suggesting the persistence of viral ribonucleic acid on nasopharyngeal swabs for more than 20 days, rehabilitation stays were extended up to day 24 and beyond.13 For patients after day 14, less strict prevention procedures were implemented, involving the sole use of medical masks and hand disinfection with hydroalcoholic gel.

Logistics and equipment

A physiotherapy space was arranged at the floor level for the patients after day 14 to minimize patient transportations and ease access to therapy activities. In addition, individual rehabilitation equipment was made available in each patient room, including dumbbells, training bands, pedal boards, hand cycles, and chairs of standardized height. Eight bicycle ergometers were available, 5 for the rooms of patients until day 14 and 3 for the physiotherapy space used by patients after 14 days.

Organization of the rehabilitation activities

Two physical therapy (PT) sessions per day were provided for each patient but were kept short (<20min) given the compromised cardiorespiratory condition and high levels of fatigability in post-COVID patients. The therapy program primarily included overall motor strengthening with body weight exercises (sit-to-stand, tiptoe stands, squats), elastics, and weights, with approximately 3 series of 10 repetitions for each exercise, according to the patients’ abilities. Respiratory rehabilitation exercises were associated, including controlled diaphragmatic breathing, with work on the inspiratory and expiratory times. Aerobic work included bicycle ergometer sessions at submaximal intensity, with monitoring of vital parameters. Finally, an individualized self-rehabilitation program was taught to patients, who were strongly advised to pursue these exercises after discharge, using specific workbooks.

In addition to this PT work, a physical education teacher organized small group sessions for patients after day 14 who were able to tolerate 1-hour long workshops (4 patients at a time, at least 4 meters apart). Two occupational therapists, 1 speech therapist, and 1 psychologist were also dedicated to the 35-bed unit. To be medically authorized, speech therapy sessions had to be provided beyond day 24, after 2 consecutive negative RT-PCR tests. The psychologist also cared for the staff.

Discharge process

To consider discharge home, patients had to be more than 14 days from symptom onset and no longer symptomatic for COVID-19 infection for at least 48 hours. Suitable home accommodation with temporary possibility of a private space was also required, as well as personal assistance if needed, and no at-risk relative at home. A specific mobile discharge team comprising a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician, a social worker, and an occupational therapist helped detect and solve any social issues encountered toward returning home. The physician of the mobile discharge team systematically provided teleconsultations after discharge. In addition, a dedicated physiotherapist insured proper execution of the self-rehabilitation exercises by video consultation. When discharge home was not possible at day 24 from symptom onset, a COVID-free rehabilitation unit was sought.

Ethics

The local ethics committee approved the study (UPEC IRB 0011558 no. 2020-064). Nonopposition to utilization of patient data were systematically pursued.

Study design and participants

A retrospective chart review of the first 100 patients admitted to the COVID-19 rehabilitation department was conducted since its opening on March 25, 2020. Inclusion criteria included age of 18 years or older and the ability and willingness to participate in 2 daily PT sessions 5 days a week. Among included patients, functional outcome criteria were analyzed for lengths of stay 72 hours or longer.

Demographics and clinical characteristics were recorded, including age, sex, date of admission, medical history, COVID-19 severity factors, clinical signs, biological and radiological data from the acute stay, drug treatments, date of discharge, length of stay, destination at discharge, and personal assistance at home, if any. The following outcomes were assessed by only 2 physiotherapists to limit variability: (1) Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living (also retrospectively assessed before the COVID episode by questioning the patient or family)14 , 15; (2) time to perform 10 full sit-to-stands as quickly as possible from a standardized 40-cm-height chair, arms folded over the chest, with respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, heart rate, and Borg scale of perceived exertion, recorded before and after16, 17, 18 (when 10 sit-to-stands could not be completed, the number of completions in 1 minute was collected; and (3) hand grip strength using dynamometry (the forearm was resting on the thigh, palm upward, elbow to the body at 90-degree flexion; the best result of 2 tries was kept for each side).19 , 20

Changes in these outcomes from admission to discharge were measured in all patients, and then compared between patients who stayed in ICU vs patients who did not and patients who stayed in acute care longer than the median length of stay vs those with shorter stays. Correlations between outcomes were also explored.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for quantitative continuous variables using mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Qualitative data were compared using chi-squared tests. Comparisons between admission and discharge values were carried out by paired sample t tests or Wilcoxon signed ranked tests. Correlations between Barthel total score and other functional tests and between functional scores and time spent in acute care were explored by Spearman or Pearson tests. Between-group comparisons were made using independent samples t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests. Patients with missing data upon admission or discharge were excluded from the statistical analysis for the relevant parameter. All statistical analyses were performed according to conditions of normality on Shapiro-Wilk tests. SPSS v25 softwarea was used, with a significance set at 0.05.

Results

Population description

The descriptive characteristics of the 100 patients are presented in table 1 . On admission, the median patient age was 66; 41% were older than 70years old. A total of 66% were men, the mean body mass index was 26 kg/m2, and the mean delay post-onset was 20.4±10.0 days. At the time of diagnosis, the main clinical symptoms were dyspnea with fever, and 26% had more than 50% pulmonary damage on CT scans. There was a high prevalence of hypertension (48%) and diabetes (29%). In terms of prior drug treatment, 37% had received hydroxychloroquine, 9% had received liponavir, 5% had received tocilizumab, and 6% had received corticosteroids. A total of 23% of the patients had been admitted to the ICU and 77% had needed oxygen. Upon admission to rehabilitation, 58% still required oxygen, which was administered with nasal cannula (table 2 ). The severity of admitted patients worsened over the course of the epidemic wave as the proportion of ICU and intubated patients gradually increased to reach 60% and 50%, respectively, by May 15, 2020, which was the admission date of the 100th patient. Of note, there was a discrepancy between the number of patients hospitalized in the ICU and those who were intubated (supplemental fig S1; available online only at http://www.archives-pmr.org/). Indeed, the general consensus was to limit orotracheal intubation to a strict minimum to avoid complications related to this procedure.21 In parallel, the number of days since the onset of infection at admission also gradually increased (see supplemental fig S1A). The number of weekly admissions followed the spring pandemic’s curve, peaking at 25 (supplemental figs S1B and 2).

Table 1.

Population characteristics

| Demographics | Value, n (%)∗ |

|---|---|

| Age, median ± IQR, y | 66±22 |

| Sex (Male) | 66 (66) |

| Mean delay post-onset at admission | 20.4±10.0 |

| Mean delay post-onset at discharge | 32.7±10.7 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 26.0±5.4 |

| Clinical Characteristics at Time of Diagnosis |

Value, n (%) |

| Dyspnea | 79 (79) |

| Asthenia | 76 (76) |

| Fever | 73 (73) |

| Cough | 64 (64) |

| Myalgia | 33 (33) |

| Diarrhea | 25 (25) |

| Ageusia | 16 (16) |

| Headache | 14 (14) |

| Anosmia | 13 (13) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 4 (4) |

| Thrombosis | 1 (1) |

| Background and Comorbidities |

Value, n (%) |

| High blood pressure | 48 (48) |

| Age >70 y | 41 (41) |

| Diabetes | 29 (29) |

| BMI >30 | 17 (17) |

| Renal failure | 13 (13) |

| Coronaropathy | 1 (1) |

| Stroke | 9 (9) |

| Immunosuppression | 3 (3) |

NOTE. N=100; n≥95 for all collected data. Delays expressed in days.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Unless specified otherwise.

Table 2.

Characteristics of hospital stays

| Acute Care | Value, n (%)∗ |

|---|---|

| Prior intensive care | 23 (23) |

| Intubation | 13 (13) |

| Duration of intubation, mean ± SD | 8.2±8.5 |

| Nasal O2 at admission | 77 (77) |

| Nasal O2 at discharge | 58 (58) |

| Overall length of stay in acute care, mean ± SD | 14.4±8.7 |

| In intensive care, mean ± SD | 13.8±9.0 |

| In acute care after ICU, mean ± SD | 10.22±4.87 |

| In acute care if no ICU stay, mean ± SD | 11.65±6.48 |

| Rehabilitation Care |

|

| Length of stay, mean ± SD | 9.8±5.1 |

| Deaths | 2 (2) |

| At Discharge |

|

| Overall duration of O2 dependency, mean ± SD | 17.4±11.1 |

| O2 dependency at discharge | 3 (3) |

| Discharge home | 75 (75) |

| Discharge to a relative's home | 4 (4) |

| Transfer to a COVID-free rehabilitation unit | 15 (15) |

| Transfer to acute care | 8 (8) |

| Personal assistance before COVID | 19 (19) |

| Personal assistance after COVID | 24 (24) |

NOTE. N=100; n≥99 for all collected data. Duration and length of stay expressed in days.

Abbreviation : SD, standard deviation.

Unless specified otherwise.

The mean length of stay in the rehabilitation unit was 9.8±5.6 days, with 79% of discharges home or to a relative’s home and 15% transfers to COVID-free units for further inpatient rehabilitation. The proportion of patients needing personal assistance at home increased by 26% (P<.001) as compared with before the infection, and 3% of patients still needed oxygen at discharge (table 2).

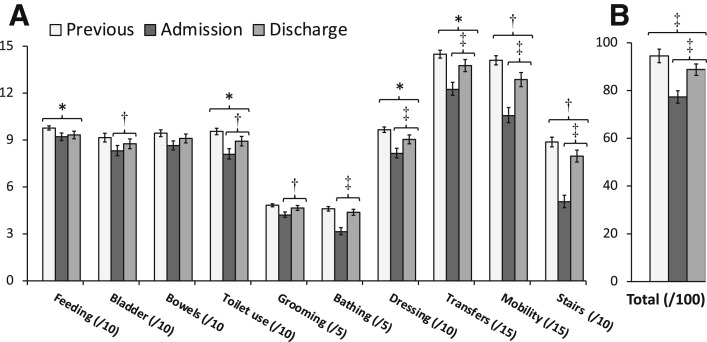

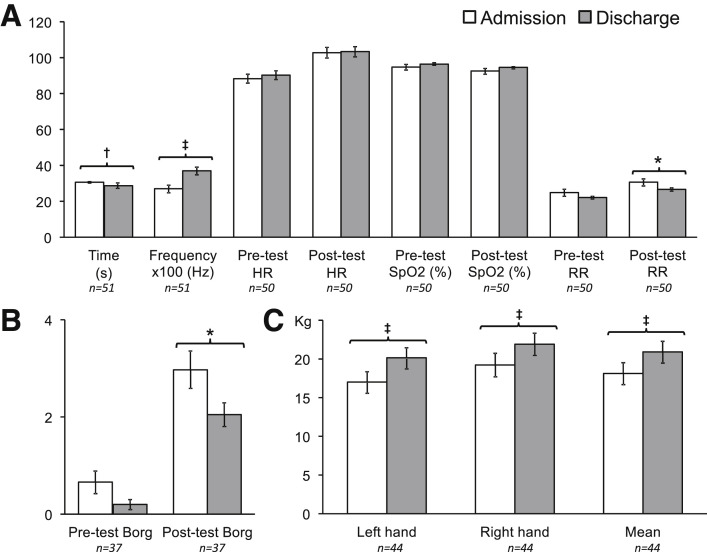

Overall functional outcomes

The total Barthel score improved from admission to discharge (77.3±26.7 vs 88.8±24.5 respectively; P<.001), particularly in terms of personal care and motor skills (transfers, walking, and use of stairs). However, independence for personal tasks of daily living at discharge remained lower than prior to infection (88.8±24.5 vs 94.5±16.2 respectively; P=.001) (fig 1 ). Sit-to-stand frequency increased by 37% (0.27±0.16 to 0.37±0.16 Hz; P<.001) (fig 2 A). Post-sit-to-stand test respiration rate dropped by 9% (30.1±12.0 to 28.0±7.5; P=.029) (fig 2A). Borg exertion score after the sit-to-stand test improved by 30% (3.0±2.4 to 2.1±1.5; P=.023) (fig 2B). Grip strength among right-handed people (92% of patients) increased by 15% (18.1±9.25 to 20.9±8.9 kg, P<.001) (fig 2C).

Fig 1.

Changes in Barthel index (n=89). (A) Barthel index items; items laid out to highlight motor tasks. (B) Barthel index total score. Data expressed in mean ± standard error of the mean. ∗P<.05. †P<.01. ‡P<.001.

Fig 2.

Functional data upon admission and at discharge. (A) Sit-to-stand parameters; (B) Borg scale before and after sit-to-stand test; (C) Grip strength in right-handed patients. Data expressed in mean ± standard error of the mean. ∗P<.05. †P<.01. ‡P<.001.

Correlations between length of acute stay, motor parameters, and functional autonomy

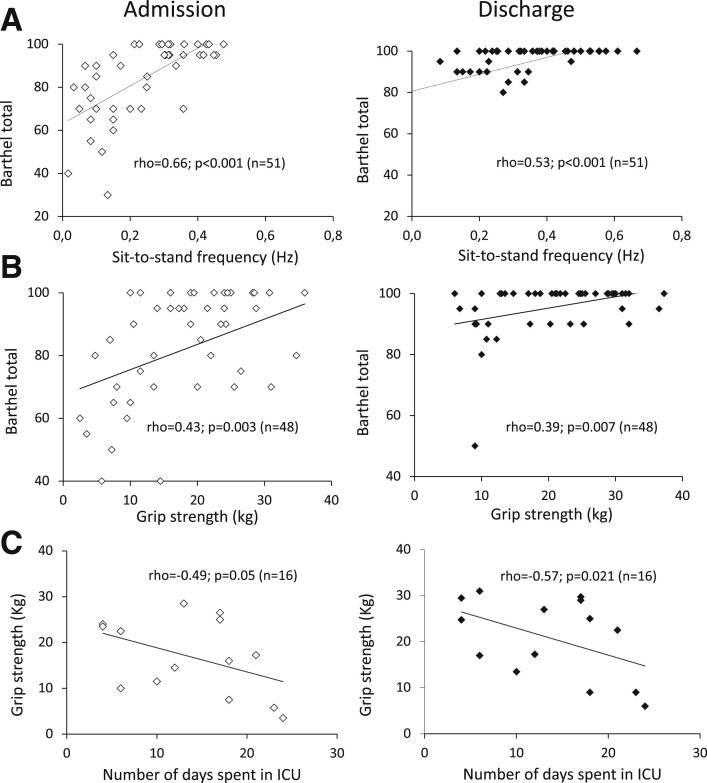

Barthel total score correlated with sit-to-stand frequency, both at admission and discharge (ρ=0.66, P<.001 and ρ=0.53, P<.001 respectively) (fig 3 A) and with grip strength both at admission and discharge (ρ=0.43, P=.003 and ρ=0.39, P=.007 respectively) (fig 3B). Grip strength was negatively correlated with the number of days spent in the ICU, both at admission and discharge (ρ=-0.49, P=.053 and ρ=-0.57, P=.021, respectively) (fig 3C), as was post-test Borg at discharge (ρ=-0.51, P=.042).

Fig 3.

Correlations between motor and functional tests and Barthel index or number of ICU days. (A) Barthel total score and sit-to-stand frequency at admission and discharge. (B) Barthel total score and mean grip strength at admission and discharge. (C) Grip strength and number of days spent in the ICU at admission and discharge. Spearman or Pearson tests were used according to conditions of normality on Shapiro–Wilk tests. Outliers beyond 2 standard deviations on Z-tests were excluded.

Between-group comparisons

Prior to admission to rehabilitation, the median length of stay in acute care was 14 days. The patient groups considered for comparison were therefore: (1) ICU vs non-ICU stays and (2) 14 days or longer vs less than 14 days in acute care. The mean length of stay in the COVID rehabilitation department was not different between these groups: post-ICU patients (n=23) spent 9.4±4.2 days in our unit vs 9.9±5.3 days among non-ICU patients (n=77) (P=.86), and patients who spent 14 days or longer in acute care (n=50) had spent 10.1±5.1 days in our unit vs 9.5±5.0 days for those who spent less than 14 days in acute care (n=50) (P=.54). There was also no difference in functional parameters upon admission into rehabilitation between these same groups, including for grip strength and Barthel index. Yet, comparisons of changes in functional outcomes from admission to discharge revealed 2 differences between the groups. Grip strength improved more in post-ICU patients (+3.3±3.1 kg; n=13) vs patients who did not require ICU (+0.99±3.7 kg; n=31; P=.049; data not shown). In addition, the score for transfers on the Barthel Index improved more in patients who stayed in acute care for 14 days or longer (+30.0±60.7%; n=45) than in patients who stayed for less than 14 days (+8.7±22.3%, n=45; P=.041; data not shown).

Discussion

In this retrospective study on the first 100 patients with COVID-19 infection admitted to a specialized rehabilitation unit, inpatient therapy was associated with substantial functional, motor, and cardiorespiratory improvement, particularly in patients who had undergone severe acute disease. Nonetheless, loss of autonomy and motor weakness persisted at discharge, which occurred approximately a month after the onset of COVID-19.

Usefulness of a COVID rehabilitation unit

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to report quantified, systematically collected data on rehabilitation effects in such a large cohort of COVID patients. It is worth mentioning that this work came in the midst of a trend to convert many rehabilitation facilities into acute departments in several countries.22 In that context, the present study still suggests the importance of early inpatient COVID rehabilitation, within 3 weeks of disease onset, including sustained motor exercises. Our findings confirmed early reports from around the world: a recent Japanese case report showed a comparable improvement on grip strength and Barthel index in 1 patient with early rehabilitative care, and an Italian review of post-COVID clinical status upon admission into rehabilitation also observed low Barthel Index total scores (<50).23 , 24 More recently, 2 studies compared functional data between admission and discharge from a specialized rehabilitation unit, from smaller sample sizes. The first study mainly provided respiratory data for 23 patients, whereas the second provided other functional data for 41 patients. As in the present work, both studies showed an improvement in Barthel index and suggested that the neurologic consequences of COVID infection could be long-lasting.6 , 7

In this study, most patients admitted to the rehabilitation unit were men, elderly, and had a high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities, all characteristics consistent with COVID-19 infection risk and severity factors previously reported.25, 26, 27 The estimated Barthel index prior to the episode was greater than 90 out of 100, showing that these patients were free of prior limitation of daily activities. Barthel at admission in rehabilitation was thus notably low (77.3±26.7), with 5% of the patients having even lost all autonomy for daily activities (ie, Barthel <30). Upon admission, there was marked motor weakness in this nongeriatric population mostly free of premorbid neurologic disability, with a mean grip strength and a sit-to-stand frequency both at 80% of normal values in that age range. At discharge, mean grip strength remained 10% below normal.17 , 18 , 28 Therefore, in this study, much of the postacute functional consequences appeared to be motor. The question may arise as to whether such motor impairment may be attributable to sole deconditioning in patients who were hospitalized for several days or to direct COVID-19 aggression of neurologic pathways.29, 30, 31, 32, 33

Any effect of COVID-19 on the nervous system is being scrutinized in the literature. A literature review with meta-analysis outlines possible neurologic symptomatology.34 The sole known neurologic disorders observed in the present series were probable ICU-acquired weakness (unfortunately, however, electroneuromyography was not systematically performed in the present cohort) and a few post-intubation swallowing disorders. We did not note any emerging confusion related to the COVID-19 infection in a context where some of our patients did have preexisting cognitive impairments. One patient experienced an acute stroke for which he was initially hospitalized and was then incidentally diagnosed with COVID-19. In the presence of other risk factors, this stroke was not attributed to the ongoing COVID infection.

Most of the rehabilitative therapy involved motor exercises and few pure respiratory exercises. Accordingly, motor progression was dramatic during the hospital stay and functional autonomy highly correlated with motor performance. This made sense since the sit-to-stand test and grip strength have been shown to correlate with overall strength and global physical functioning, thus assumingly with the Barthel Index.15 , 17 The mean length of rehabilitation stay (9.8±5.0d) was notably shorter than in a traditional inpatient rehabilitation setting. This may have resulted from both the intensity of the rehabilitative care provided and the effectiveness of the mobile team specifically dedicated to accelerate the discharge process.

Recovery was incomplete at discharge, which may imply the need to continue with outpatient rehabilitation beyond discharge. To this end, because outpatient physiotherapy was forbidden during the spring pandemic, patients were taught guided self-rehabilitation exercises and were provided with a workbook containing an individualized program, similar to what exists in other indications.35 A more prolonged stay might have allowed a more complete recovery.

Effect of motor rehabilitation on severe COVID cases

The findings suggest that an ICU or longer acute stay did not hamper responsiveness to rehabilitation. In fact, responsiveness was even enhanced for some outcomes in these severely affected patients. Admittedly, motor function may have started from lower values in these cases, even though differences upon admission into rehabilitation were not statistically significant between the groups. Nevertheless, these findings are reassuring, because they support the reversibility of much of the motor consequences of longer stays in acute care or of ICU stays.

Study limitations

The present study is not controlled. In the context of the health crisis of Spring 2020, it was not considered ethical to conduct a clinical trial of rehabilitation vs a "sham rehabilitation" control group. The lack of hindsight in this disease and the emergencies with which professionals were faced also made it impossible to design a control group with a real but different rehabilitation protocol. Another limitation was the proportion of missing functional data. Due to rapid patient turnover, functional assessments could not always be conducted. However, data were sufficient to show pre-post and between-group statistical differences. Respiratory data were also incomplete, although these would have allowed us to better characterize and follow-up with patients. Spirometry was not assessed, as there was concern about the infectious risk of its use, and Pa/Fio2 measurements were not possible because patients admitted in rehabilitation were not ventilated, as per inclusion criteria.

Conclusions

When the COVID-19 health crisis began, several reports emphasized the need to be prepared for postacute care management.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The objective, quantified functional improvement from admission to discharge suggests the usefulness of rehabilitation in a specialized unit after COVID-19 infection, with even greater improvement for some outcomes in patients who had undergone ICU or stayed longer in acute care. However, the consequences of severe COVID-19 infection on dependence appear to be long-lasting and predominantly related to motor limitation. Once the acute hospital situation has subsided, prospective and randomized blinded studies comparing the effectiveness of different types of rehabilitation and including specific respiratory assessments may further knowledge on COVID rehabilitation.

Supplier

-

a.

SPSS, v. 25; IBM Corp.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none.

Covid Rehabilitation Study Group: Violaine Piquet, MBS, Cédric Luczak, MBS, Fabien Seiler, PT, Jordan Monaury, PET, Estelle Lépine, PT, Lucile Chambard, PT, Marjolaine Baude, MD, Emilie Hutin, PhD, Alexandre Martini, MD, Andrés Samaniego, MD, Nicolas Bayle, MD, Anthony B Ward, MD, Jean-Michel Gracies, MD, Damien Motavasseli, MD.

Contributor Information

Covid Rehabilitation Study Group:

Violaine Piquet, Cédric Luczak, Fabien Seiler, Jordan Monaury, Estelle Lépine, Lucile Chambard, Marjolaine Baude, Emilie Hutin, Alexandre Martini, Andrés Samaniego, Nicolas Bayle, Anthony B. Ward, Jean-Michel Gracies, and Damien Motavasseli

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Simpson R., Robinson L. Rehabilitation after critical illness in people with COVID-19 infection. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99:470–474. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabowski D.C., Joynt Maddox K.E. Post-acute care preparedness for COVID-19: thinking ahead. JAMA. 2020;323:2007–2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carda S., Invernizzi M., Bavikatte G., et al. The role of physical and rehabilitation medicine in the COVID-19 pandemic: the clinician's view. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;63:554–556. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrenelli E., Negrini F., De Sire A., et al. Rehabilitation and COVID-19: a rapid living systematic review 2020 by Cochrane Rehabilitation Field. Update as of September 30th, 2020. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56:846–852. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06672-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iannaccone S., Castellazzi P., Tettamanti A., et al. Role of rehabilitation department for adult individuals with COVID-19: the experience of the San Raffaele Hospital of Milan. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:1656–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puchner B., Sahanic S., Kirchmair R., et al. Beneficial effects of multi-disciplinary rehabilitation in post-acute COVID-19 - an observational cohort study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2021 Jan 15 doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.21.06549-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curci C., Negrini F., Ferrillo M., et al. Functional outcome after inpatient rehabilitation in post-intensive care unit COVID-19 patients: findings and clinical implications from a real-practice retrospective study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2021 Jan 4 doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06660-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ngai J.C., Ko F.W., Ng S.S., To K.-W., Tong M., Hui D.S. The long-term impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity and health status. Respirology. 2010;15:543–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01720.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herridge M.S., Tansey C.M., Matté A., et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herridge M.S., Moss M., Hough C.L., et al. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:725–738. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuke R., Hifumi T., Kondo Y., et al. Early rehabilitation to prevent post-intensive care syndrome in patients with critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.To K.K.-W., Tsang O.T.-Y., Leung W.-S., et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ai T., Yang Z., Hou H., et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296:E32–E40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wade D.T., Collin C. The Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10:64–67. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collin C., Wade D.T., Davies S., Horne V. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10:61–63. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csuka M., McCarty D.J. Simple method for measurement of lower extremity muscle strength. Am J Med. 1985;78:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mateos-Angulo A., Galán-Mercant A., Cuesta-Vargas A.I. Muscle thickness contribution to sit-to-stand ability in institutionalized older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:1477–1483. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scherr J., Wolfarth B., Christle J.W., Pressler A., Wagenpfeil S., Halle M. Associations between Borg’s rating of perceived exertion and physiological measures of exercise intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:147–155. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohannon R.W. Muscle strength: clinical and prognostic value of hand-grip dynamometry. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18:465–470. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan P.-J., Lin C.-H., Yang N.-P., et al. Normative data and associated factors of hand grip strength among elderly individuals: The Yilan Study, Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2020;10:6611. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navas-Blanco J.R., Dudaryk R. Management of respiratory distress syndrome due to COVID-19 infection. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020;20:177. doi: 10.1186/s12871-020-01095-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boldrini P., Kiekens C., Bargellesi S., et al. First impact of COVID-19 on services and their preparation. "Instant paper from the field" on rehabilitation answers to the COVID-19 emergency. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56:319–322. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curci C., Pisano F., Bonacci E., et al. Early rehabilitation in post-acute COVID-19 patients: data from an Italian COVID-19 Rehabilitation Unit and proposal of a treatment protocol. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56:633–641. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06339-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saeki T., Ogawa F., Chiba R., et al. Rehabilitation therapy for a COVID-19 patient who received mechanical ventilation in Japan. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99:873–887. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo L., Wei D., Zhang X., et al. Clinical features predicting mortality risk in patients with viral pneumonia: the MuLBSTA score. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2752. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang L., Karakiulakis G., Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e21. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Billy L., Martini A., Savard E., Cosme S., Gracies J.M. Intra- and inter-rater reliability and validity of a clinical and quantifying test of the sit-to-stand task in Parkinsonian syndromes. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2018;61:e253. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baig A.M., Khaleeq A., Ali U., Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:995–998. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montalvan V., Lee J., Bueso T., De Toledo J., Rivas K. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronavirus infections: a systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;194:105921. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez-Gonzalo R., Tesch P.A., Lundberg T.R., Alkner B.A., Rullman E., Gustafsson T. Three months of bed rest induce a residual transcriptomic signature resilient to resistance exercise countermeasures. FASEB J. 2020;34:7958–7969. doi: 10.1096/fj.201902976R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brower R.G. Consequences of bed rest. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10 Suppl):S422–S428. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6e30a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arentson-Lantz E.J., English K.L., Paddon-Jones D., Fry C.S. Fourteen days of bed rest induces a decline in satellite cell content and robust atrophy of skeletal muscle fibers in middle-aged adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2016;120:965–975. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00799.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdullahi A., Candan S.A., Abba M.A., et al. Neurological and musculoskeletal features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2020;11:687. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gracies J.M. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2016. Guided self-rehabilitation contract in spastic paresis. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.