Abstract

True cardiac arteriovenous malformations are rare anomalies that may be acquired or congenital in origin. These anomalies are well demonstrated by Multi Detector Computed Tomography (MDCT) with much higher clarity and anatomic detail than invasive angiography. We report a case of large complex cardiac vascular malformation in 55 year old male involving feeders from systemic (internal mammary artery, right inferior phrenic artery), coronary (left anterior descending), and pulmonary arterial and venous systems using a 64 slice MDCT scanner. Cardiac AV malformations have previously been described using MDCT, but this case is unique in terms of its large size, extensive involvement of systemic, coronary and pulmonary vascular connections, and mild clinical symptomatology. Our case shows that patients with complex coronary malformation may not always require treatment as natures’ pathways may work well throughout lifetime.

KEYWORDS: CT Computed Tomography, AVM Arteriovenous Malformation, CABG Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

Introduction

Coronary Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) are exceedingly rare anomalies that consist of abnormal communication between coronary artery and one of the chambers of heart (known as coronary cameral fistula) or adjacent vessels. Coronary AVMs may result in myocardial ischemia due to steal phenomenon, bacterial endocarditis and heart failure, or may be entirely asymptomatic. In case of large arteriovenous shunts, severe ischemia and even death may result [1]. We report a case of complex arteriovenous malformation involving the left anterior descending, left internal mammary, right inferior phrenic and left upper lobe pulmonary artery and left superior pulmonary vein) diagnosed during coronary CTA using a 64 slice CT.

Case report

A 55-year old male with intermediate risk factors for coronary artery disease and episodic mild chest pain on exertion was referred for CT coronary angiography to our department. On physical examination the patient had a short systolic murmur at apex while ECG was normal. Echocardiography was done and was unremarkable. The past history was unremarkable with no catheter angiography, surgery or trauma. The imaging was performed on a 64 slice Multi Detector Computed Tomography (MDCT) scanner(Sensation Cardiac 64, Siemens Medical Solutions) after premedication with oral β- blocker metoprolol (50mg) with additional 2 boluses of iv metoprolol (5mg each) at the commencement of the study to decrease the heart rate .We use a protocol of retrospective ECG gating with automated bolus triggering (the trigger being placed on mid ascending aorta and setting the threshold for scan initiation at 160 HU), a collimation of 64 × 0.6mm, kV 120 and effective mAs 800. The raw data was reconstructed (using 0.6mm thick slices with 0.4mm overlap, B35 kernel) at 35%, 55% and 65% of R-R interval using a dedicated cardiac workstation; we also routinely perform multiphase reconstruction at 10% R-R interval for functional analysis. The study revealed a complex tangle of vessels on the anterolateral surface of mid left ventricle. Elongated tortuous feeders were seen arising from left internal mammary artery, enlarged right inferior phrenic artery and diagonal branches of left anterior descending artery (Fig. 1 and 2). The AVM was draining into the left pulmonary circulation (a branch of left superior pulmonary vein and a small communication with left upper lobe pulmonary artery) (Fig. 3). Our patient refused further evaluation with catheter angiography and is on follow up.

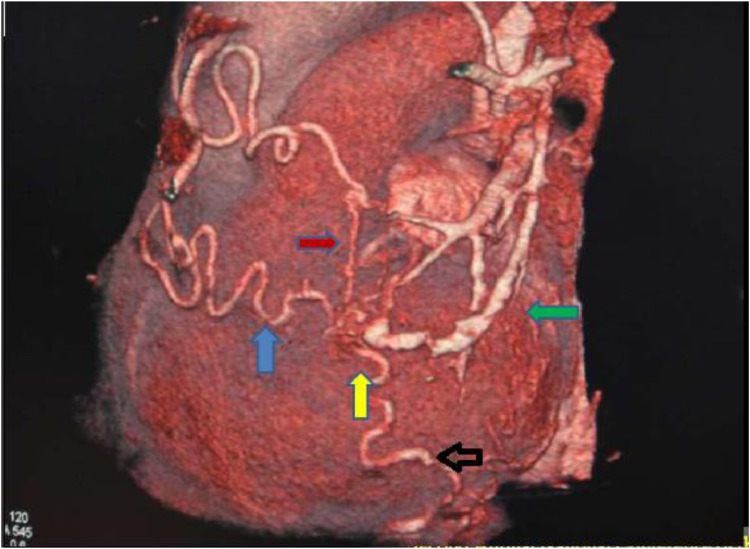

Fig. 1.

Volume rendered image (anterior view) demonstrates a vascular malformation (yellow arrow) fed by tortuous feeders from left internal mammary (black arrow), right inferior phrenic and LAD twigs (red arrow) with drainage into left superior pulmonary vein (green arrow).

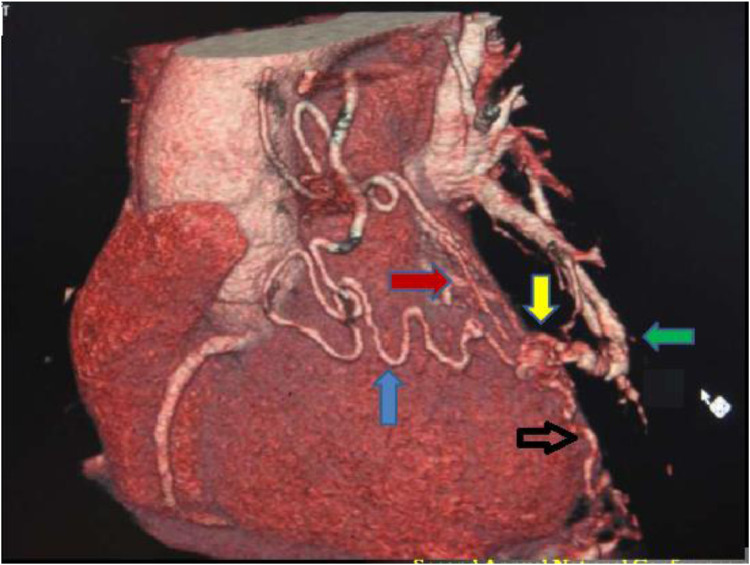

Fig. 2.

The VRT image of the malformation as viewed from the left lateral aspect showing the left internal mammary (blue arrow), right inferior phrenic (black arrow), and pulmonary vascular contributions (green arrow).

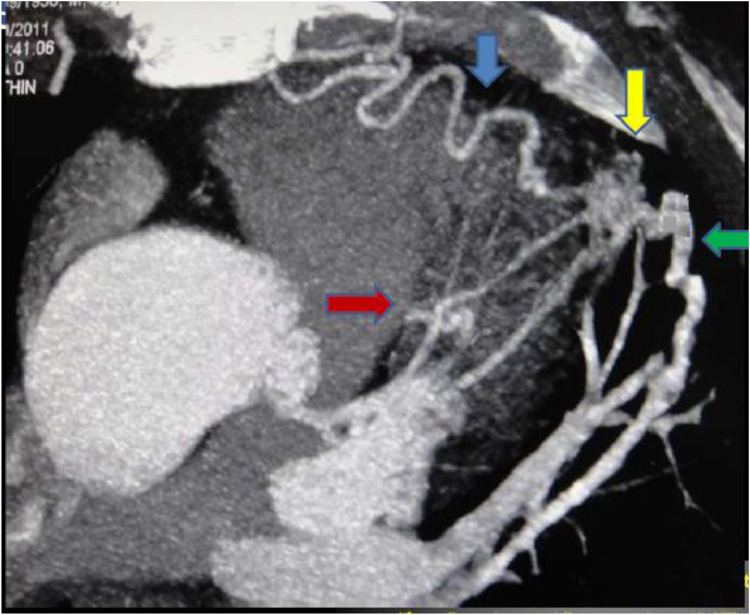

Fig. 3.

Oblique axial MIP image showing the tortuous internal mammary feeder (blue arrow), the diagonal branch of LAD (red arrow) and left superior pulmonary artery and vein (green arrow) connected to the vascular malformation (yellow arrow) that is seen as a vascular tangle.

Discussion

Coronary AV malformations are rare anomalies (1 in 50000 live births) that may be congenital or acquired. They constitute about half of coronary artery anomalies and are usually hemodynamically significant. Coronary AVMs may be present as an isolated finding (55%-80% cases) or be associated with other congenital heart diseases (ASD, TOF, PDA etc) . The most common site of origin is RCA (55%) followed by LAD (35%); multiple malformations may occur in 10.7%-16% of cases. Most fistulas drain into the right sided chambers (RV -40%, RA -26%, PA -17%, coronary sinus-7% and SVC 1%). In about 3%-5% cases, the AVM may drain into left sided cardiac chambers [1], [2], [3]. The acquired causes of coronary artery fistulas include trauma, surgery, endomyocardial biopsy or angiography. Most of these fistulas are small and patients remain asymptomatic (55%). Large shunts can result in ischemia secondary to steal; these may manifest as chest pain (34%) and congestive heart failure (13%). Coronary cameral fistulas to left heart chambers can result in signs and symptoms of aortic valve insufficiency [2,4].

Till now invasive coronary angiography has been the mainstay of diagnosis of coronary anomalies. This is associated with 2 problems: one is a definite procedure associated morbidity (1.5%) and mortality (0.15%); second, owing to the 2-dimensional nature of invasive coronary angiography the exact 3-dimensional relationship between the vascular malformation and cardiac chambers is not optimally depicted. MDCT is currently the investigation of choice for evaluation of coronary anomalies. The usual technique adopted is acquisition of data using a retrospective ECG gating, with ECG tube dose modulation (for reduction of radiation dose), reconstruction of data in different phases chosen to minimize motion artifacts. If heart rates of less than 65 bpm are achieved with an adequate breath-hold, excellent images can be obtained with a 64 slice MDCT scanner that compare favorably with those obtained at invasive angiography [2,3]. The excellent 3D anatomic detail obtained by means of a MDCT helps in the management decision and provides a roadmap for the interventionist. MRI also has been evaluated for assessment of coronary anomalies especially in patients with congenital heart disease. MRI'S advantage of lack of radiation is partially offset by its less than optimal spatial resolution (1-25 × 1.25 × 1.5) with suboptimal evaluation of distal coronaries and smaller collateral vessels. It is also technically more demanding and more time consuming [5]. Perfusion MRI (with or without pharmacologic stress) has, however, the potential of assessing the extent of myocardial ischemia associated with a vascular malformation, thereby helping in management decision.

The treatment of choice for symptomatic coronary artery fistulas and AVMs is transcatheter embolization. However, multiple fistulae, multiple drainage sites and presence of large branch vessels are exclusion criteria for transcatheter embolization. Surgical closure by epicardial and endocardial ligations (with or without cardiopulmonary bypass) is a safe and effective method of treatment [6,7].

The patient described in this report had mild symptoms, refused catheter angiography, was managed medically and is under follow-up. The extensive systemic vascular feeders (internal mammary artery, inferior phrenic artery) and connections with pulmonary arterial and venous system had produced a balanced hemodynamics that had maintained myocardial perfusion for 4 decades. This anomaly bears a more than superficial resemblance to CABG surgery (LIMA-LAD graft) and may be aptly termed as bypass surgery performed by nature.

Acknowledgments

Funding

No funding or grant support.

Disclosures

No relationship with any industry.

Consent

Written consent from the patient was obtained with the condition that the identity would not be revealed.

Acknowledgment

Department of cardiology SKIMS.

Footnotes

Authorship: All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

References

- 1.Khachattiyan T, Karnwal S, Hamirani YS, Budoff MJ. Coronary arteriovenous malformations as imaged with cardiac computed tomography angiography: a case series. J Radiol Case Rep. 2010;4:1–8. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v4i4.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zenooz NA, Habibi R, Mammen L, Finn JP, Gilkeson RC. Coronary artery fistulas: CT findings. Radiographics. 2009;29:781–789. doi: 10.1148/rg.293085120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaina AR, Blender J, Sharif D, Rosenchein U, Barmier E. Congenital coronary anomalies in adults: non invasive assessment with multidetector CT. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:254–261. doi: 10.1259/bjr/80369775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang DS, Lee MH, Lee HY, Barack BM. MDCT of left anterior descending coronary artery to main pulmonary artery fistula. AJR. 2005;185:1258–1260. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parga JR, Ikari NM, Bustamente LN, Rochette CE, de Anla LF, Olieveira SA. Case report: MRI evaluation of congenital coronary artery fistulas. Br J Radiol. 2004;77:508–511. doi: 10.1259/bjr/24835123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg SL, Makkar R, Duckwiler G. New strategies in the percutaneous management of coronary artery fistulas: a case report. Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;61:227–232. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamiya H, Yasuda T, Nagamine H. Surgical treatment of congenital coronary artery fistulas: 27 years experience and review of literature. J Cardiol Surg. 2002;17:173–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2002.tb01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]