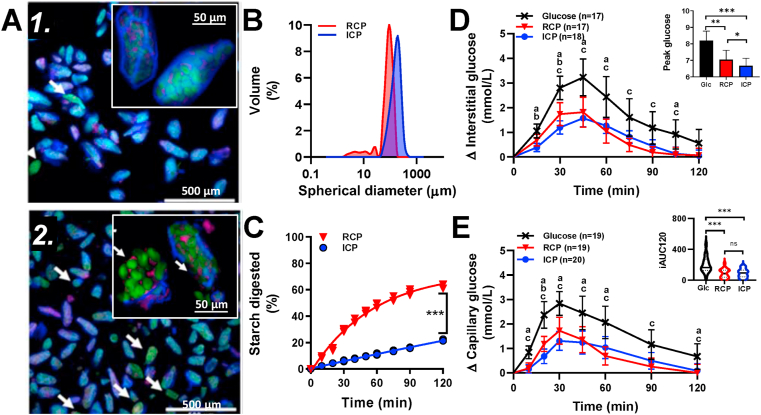

Fig. 1.

Cell powder characteristics and mechanism. Confocal images of intact (A1) and ruptured (A2) cell powders (‘ICP’ and ‘RCP’). Cell walls (blue), starch (green) and protein (red). Arrows highlight damaged cells. Particle size distributions (B); starch amylolysis (C) curves show highly significant differences between ICP and RCP; incremental glycaemic responses in interstitial fluid (D) and capillary blood (E) as means ± 95% CIs for number of participants (n) after drinks of glucose (‘glc’) X, RCP ▼ and ICP ●, each containing 58 g of potentially available carbohydrate (predominantly as glucose in ‘glc’ or as starch in RCP and ICP). Bar chart (insert D) shows mean peak glucose concentration with 95% CIs. Violin plots (insert E) show distribution and median incremental area under the curves, ‘iAUC120’. Significant differences between drinks annotated: a – glc vs ICP; b – ICP vs RCP and c-glc vs RCP.