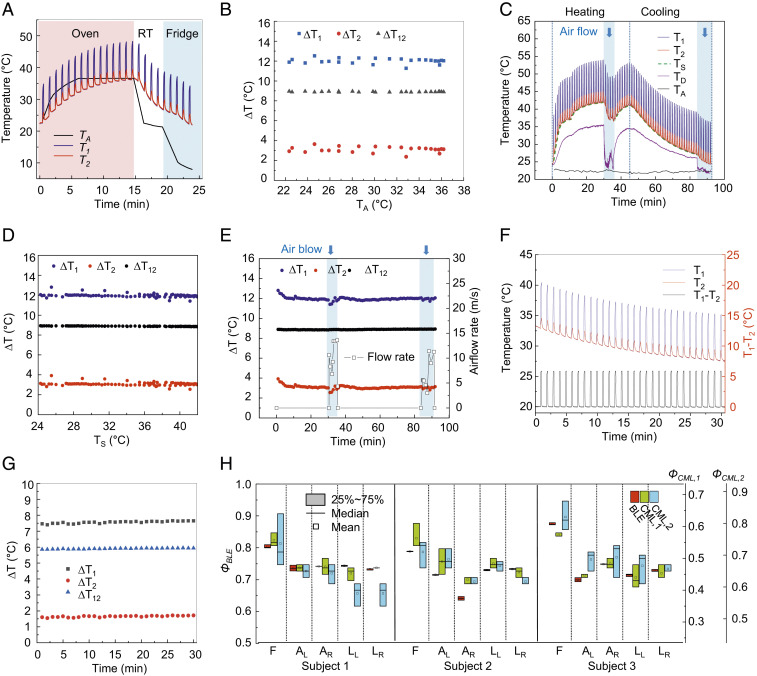

Fig. 3.

Experimental studies under various practical conditions. (A) Wireless measurements of T1 (blue) and T2 (red) in various ambient temperatures (TA) in an oven and a refrigerator (red and blue background, respectively), and at room temperature (RT). (B) Measurements of ∆T1 (blue), ∆T2 (red), and ∆T12 (black) as a function of TA. (C) Wireless measurements of T1 (blue), T2 (red), and substrate temperature (TS; green dashed line) on/off the hot plate (heating/cooling, respectively) and with different levels of airflow, as a function of time. The surface temperature of the top encapsulation corresponds to that directly above the heating/sensing elements of the device (TD; purple) and the ambient temperature (TA; black) was determined using a commercial thermometer. (D and E) Measurements of ∆T1 (blue), ∆T2 (red), and ∆T12 (black) as a function of TA (D) and as a function of time (E). A pneumatic flow valve controls the flow of air over the device. (F and G) Wireless measurements of T1 (blue), T2 (red), and the difference (T1 − T2; black) as a function of time (F), and of ∆T1 (blue), ∆T2 (red), and ∆T12 (black) as a function of time (G) underwater. (H) Skin hydration levels (Φ) measured by three users at the same set of body locations using the BLE device (ΦBLE), and commercial devices for measuring tissue water content (ΦCML,1) and skin surface hydration levels (ΦCML, 2). Five different body locations: forehead (F), right arm (AR), left arm (AL), right leg (LR), and left leg (LL).