Abstract

Background:

Prolonged operative time and intraoperative hypothermia are known to have deleterious effects on surgical outcomes. Although millions of burn injuries undergo operative treatment globally every year, there remains a paucity of evidence to guide perioperative practice in burn surgery. This study evaluated associations between hypothermia and operative time on post-operative complications in acute burn surgery.

Method:

A historical cohort study from January 1, 2006 to October 31, 2015 was completed at an American Burn Association verified burn centre. 1111 consecutive patients undergoing acute burn surgery were included, and 2171 surgeries were analyzed.

Primary outcomes included post-operative complications, defined a priori as either infectious or noninfectious. Statistical analysis was undertaken using a modified Poisson model for relative risk, adjusted for total body surface area, inhalation injury, co-morbidities, substance abuse, and age.

Results:

The mean operative time was 4.4h (SD 3.7–4.7h; range 0.58–11h), and 18.6% of patients became hypothermic intra-operatively. Operative time was independently associated with the incidence of hypothermia (p<0.05), and both infectious (RR1.5; 1.2–1.9, p<0.0004) and non-infectious complications (RR2.3; 1.3–4.1, p<0.0066). In patients with major burns (TBSA≥20%), hypothermia predisposed to infectious (RR1.3; 1.1–1.5, p<0.0017) and non-infectious complications (RR1.7; 1.2–2.5; p<0.0049). Risk stratification revealed that hypothermic patients with major burns undergoing prolonged surgery had an increased risk of both infectious (RR1.4; 1.1–1.7, p<0.0068) and non-infectious complications (RR1.8; 1.1–3.0, p<0.0132) when compared with those without these risk factors.

Conclusions:

Patients who undergo prolonged surgeries and become hypothermic are more likely to develop complications. We therefore advocate for diligent adherence to strategies to prevent hypothermia and recommend limiting operative time in clinical circumstances where intraoperative measures are unlikely to adequately prevent hypothermia.

1. Background

Burn injury remains a prominent global health burden, with over 11 million burn injuries receiving medical attention per annum, especially in low and middle-income countries [1]. For full thickness and deep partial thickness burns, the widely accepted practice is early excision and autografting [2,3]. While outcomes are undoubtedly improved as a result of this strategy, early aggressive debridement exposes susceptible patients to considerable potential risk in the operating room, including the development of hypothermia and its sequelae [4]. Burn surgeons have been cogniscent of this potential threat, but little objective data is available to guide practice [5,6]. A recent review by Rizzo et al. highlighted the scarcity of literature focusing on the adverse effects of intraoperative hypothermia in burn surgery and challenged the burn community to “re-evaluate current dogma” regarding surgical principles and practice [4].

Experience from other branches of surgery has recognized that hypothermia is closely related to mortality in major traumatic injuries [7], and its subsequent inclusion in the ‘lethal triad’ [8,9], contributed to the development and widespread application of ‘damage control’ surgery. Intraoperative hypothermia has been associated with increased bleeding from platelet dysfunction and coagulopathy [10], greater number of transfusions [10,11], and immunodeficiency [12]. Prolonged surgery, specifically, has been associated with infections in abdominal surgery [13] and arthroplasty [14], and with increased microsurgical free flap failure rates in plastic and reconstructive surgery [15]. Patients with burn injuries are intuitively at greater risk of hypothermia than these cohorts, not least because of the loss of cutaneous integrity (which necessitates upregulation of thermogenesis via catecholamine-induced hypermetabolism [4,16,17]).

This study aimed to determine the relationship between operative time and hypothermia, operative time and postoperative complications, and hypothermia and post-operative complications. We hypothesized that both increased operative time and hypothermia independently and in combination are associated with increased rates of post-operative complications, and that this effect would be most significant in the context of major burn injuries, defined as burn injuries exceeding twenty percent total body surface area.

2. Methods

This study was conducted at the Ross Tilley Burn Centre at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Canada. A cohort study utilizing the STROBE Statement Checklist of Items for Reports of Cohort Studies was completed, and constituted the background data collection for an ongoing quality improvement initiative at the burn centre in 2016. Approval to perform the study was granted by the local institutional research ethics board.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if all of their acute burn surgery was performed at the institution, between 2006 and 2015. Patients were identified using the NATIONAL TRACS® (NTRACS, Digital Innovation Incorporated, Forest Hill, Maryland, US) database, searching for “burn surgery”. Patients excluded from analysis were those admitted for reconstructive surgery, conditions other than burn injury, or if only part of their acute burn management was undertaken at the centre, and those for whom documentation was either absent or incomplete. Demographic data collected included sex, age, total body surface area, presence of inhalation injury, substance abuse (alcohol, cigarette, and other recreational drug use), comorbidities [18], operative details, and postoperative complications.

Operative length was defined a priori as the total duration in the operating room (from time of entry to exit). A baseline operative time cohort was determined to have had an operative time of less than three hours. Outcomes were compared with three other cohorts, specifically those patients who underwent surgeries of 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and more than 5h, respectively. For the purposes of this study, hypothermia was defined as core body temperature at or below 35°C [19–21]. The baseline cohort consisted of those who maintained a body temperature of >35°C, and a hypothermia cohort of those who manifested at least one intraoperative temperature of ≤35°C. Sub-group analysis was performed for patients with major burns (Total Body Surface Area [TBSA]≥20%).

Post-operative complications were classified as either infectious or non-infectious. Infectious complications included sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and wound infections, while non-infectious outcomes included death, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, and venous thrombo–embolus (including deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus).

A modified Poisson model was applied to obtain estimates of relative risk for binary outcomes [22]. Binary outcomes included hypothermia (≤35°C) at surgery level, and post-operative complications and infections at patient level. Statistical analyses adjusted for demographic and injury characteristics, including age, burn size, presence of inhalation injury, number of co-morbidities, as well as smoking, alcohol, and drug use. The association between operative time and hypothermia (≤35°C) was analyzed at the surgery level and adjusted for the clustering effect of surgeries within the same patient using generalized estimating equations. At the patient level, three exposure variables were analyzed for post-operative complications, including average operative time and hypothermia, across all surgeries, and the combination of these two. The present study therefore includes four ‘sub-studies’ involving four historical cohorts, with different demographics for each, which focused on:

Operative time and its association with postoperative complications.

Operative time and its association with hypothermia.

Hypothermia and its association with postoperative complications.

A post-hoc risk stratification analysis of operative time and hypothermia in patients with major burns and the association with post-operative complications.

3. Results

One thousand one hundred and eleven patients were enrolled in this cohort study, of whom 128 patients failed to meet inclusion criteria or had missing data, resulting in 983 patients studied. The demographic details of this cohort are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 48 years (SD18), they were predominantly male (70%), and had an average total body surface area (TBSA) of 14% (SD14). 49% of the burns were full thickness in depth and 14% of patients had concomitant inhalation injury. 18% of the patients underwent escharotomies. The mechanisms of injury were predominantly flame burns (68%). The length of hospital stay per percentage TBSA was 1.9 (1.2–3.3) days.

Table 1 –

Demographic information of all patients stratified by total burn size area (TBSA).

| Demographics | All patients (N=983) | TBSA<20% (N=752) | TBSA≥20% (N=231) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years, mean (SD) | 48 (18) | 47 (18) | 49 (17) | 0.250 |

| Gender female, n (%) | 297 (30) | 240 (32) | 57 (25) | 0.036* |

| Total TBSA %, mean (SD) | 14 (14) | 8 (5) | 35 (14) | <0.001* |

| 3rd degree TBSA %, median (IQR) | 49 (0–100) | 40 (0–100) | 70 (13–96) | 0.005* |

| Inhalation injury, n (%) | 137 (14) | 54 (7) | 83 (36) | <0.001* |

| Burn mechanism | ||||

| Flame, n (%) | 645 (66) | 450 (60) | 195 (84) | <0.001* |

| Scald, n (%) | 275 (28) | 242 (32) | 33 (14) | <0.001* |

| Electrical, n (%) | 58 (6) | 48 (6) | 10 (4) | 0.245 |

| Chemical, n (%) | 16 (2) | 14 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.295 |

| Contact, n (%) | 40 (4) | 38 (5) | 2 (1) | 0.005* |

| Clinical markers | ||||

| Escharotomy, n (%) | 176 (18) | 65 (9) | 111 (48) | <0.001* |

| Length of stay (days), median (IQR) | 17 (12–26) | 15 (11–20) | 32 (19–63) | <0.001* |

| LOS/TBSA (days/%), median (IQR) | 1.9 (1.2–3.3) | 2.2 (1.5–3.9) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | <0.001* |

| Number of OR, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 3 (2–5) | <0.001* |

| Number of single stage, n (%) | 541 (55) | 496 (66) | 45 (19) | <0.001* |

| Number of two-stage, n (%) | 256 (26) | 204 (27) | 52 (23) | 0.159 |

| Number of multiple stages, n (%) | 186 (19) | 52 (7) | 134 (58) | <0.001* |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| # of co-morbidities, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (0–3) | 0.988 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 440 (45) | 329 (44) | 111 (48) | 0.250 |

| Drug use, n (%) | 150 (15) | 111 (15) | 39 (17) | 0.433 |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 426 (43) | 334 (45) | 92 (40) | 0.213 |

| Post-operative complications | ||||

| Pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 10 (1) | 5 (1) | 5 (2) | 0.047* |

| Deep venous thrombosis, n (%) | 13 (1) | 8 (1) | 5 (2) | 0.200 |

| ARDS, n (%) | 49 (5) | 15 (2) | 34 (15) | <0.001* |

| Pneumonia/VAP, n (%) | 181 (18) | 55 (7) | 126 (55) | <0.001* |

| Graft loss, n (%) | 200 (20) | 110 (15) | 90 (39) | <0.001* |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 104 (11) | 19 (3) | 85 (37) | <0.001* |

| Wound infection, n (%) | 180 (18) | 92 (12) | 88 (38) | <0.001* |

| MODS, n (%) | 48 (5) | 16 (2) | 32 (14) | <0.001* |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 156 (16) | 75 (10) | 81 (35) | <0.001* |

| Mortality, n (%) | 42 (4) | 11 (2) | 31 (13) | <0.001* |

Significance at 5% level.

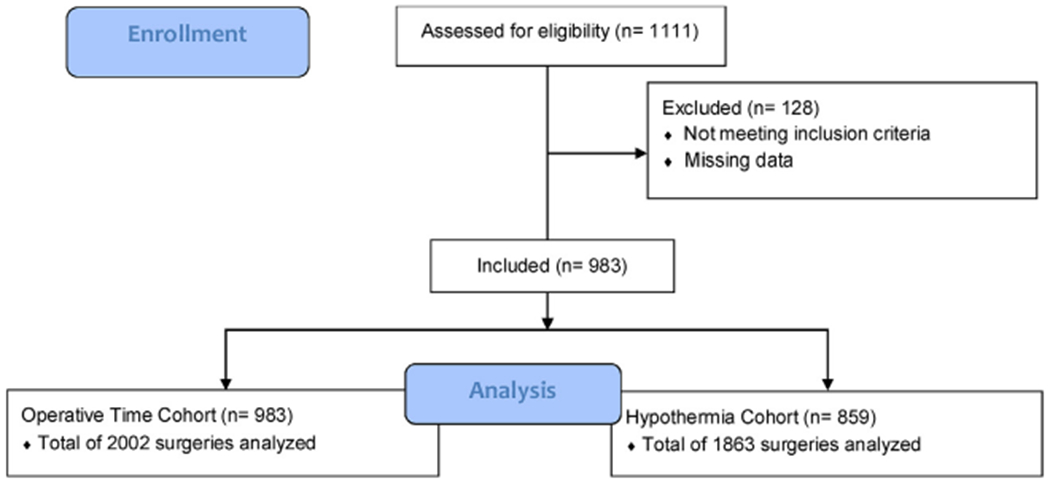

The above 1111 patients underwent a total of 2171 burn surgeries, with 2002 (92.2%) having sufficient information to be included in the operative time analysis and 1863 (85.8%) in the hypothermia analysis (Fig. 1). The majority of surgeries were single-stage (55%). The mean operative length was 4.4h (SD 3.7–4.7h; range 0.6–11h). 18.6% of patients were hypothermic at least once during their operative course. The most common post-operative complications were graft loss and infections (specifically, wound, pneumonia, and urinary tract). The mortality rate was 4%.

Fig. 1 –

Patient flow diagram.

3.1. Study A – operative time and its association with postoperative complications

The operative time cohort consisted of 983 patients who underwent 2002 surgeries (Table 1). Patients undergoing prolonged operative interventions had more extensive burn injuries (p<0.001) and sustained more concomitant inhalation injuries (p<0.001), when compared to the shorter operative time cohorts. There were no statistically significant differences in terms of sex, age, drug and alcohol use, or comorbidity counts between the different operative time cohorts. Patients who underwent longer surgeries experienced higher rates of all complications (Table 2).

Table 2 –

Operative time cohort demographics and outcomes.

| All (N=983) | <3h (N=448) | 3–3.9h (N=272) | 4–4.9h (N=175) | ≥5h (N=88) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Female, % | 30 | 31 | 30 | 31 | 26 | 0.8271 |

| Age, mean (std) | 48 (18) | 47 (18) | 47 (18) | 47 (17) | 49 (19) | 0.9063 |

| TBSA, median (IQR) | 14 (3–30) | 5 (3–10) | 13 (7–25) | 18 (10–28) | 19 (13–30) | <0.001* |

| Inhalation injury, % | 14 | 6 | 21 | 19 | 23 | <0.0001* |

| Smoking history, % | 45 | 41 | 50 | 42 | 53 | 0.0308* |

| Drug use, % | 15 | 15 | 17 | 14 | 13 | 0.6738 |

| Alcohol use, % | 43 | 41 | 48 | 45 | 36 | 0.1584 |

| Co-morbidity count, median | 2 (1–3) | 1.0 (0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 0.9039 |

| Post-operative outcomes | ||||||

| Death, % | 4 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 9 | <0.0001* |

| Pulmonary embolus, % | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0.0137* |

| Sepsis, % | 11 | 2 | 18 | 23 | 18 | <0.0001* |

| ARDS, % | 5 | 2 | 9 | 9 | 15 | <0.0001* |

| MODS, % | 5 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 9 | <0.0001* |

| Pneumonia, % | 18 | 6 | 28 | 34 | 33 | <0.0001* |

| Urinary tract infection, % | 16 | 8 | 22 | 25 | 22 | <0.0001* |

| Wound infection, % | 18 | 14 | 27 | 22 | 25 | 0.0001* |

Significance is <0.05.

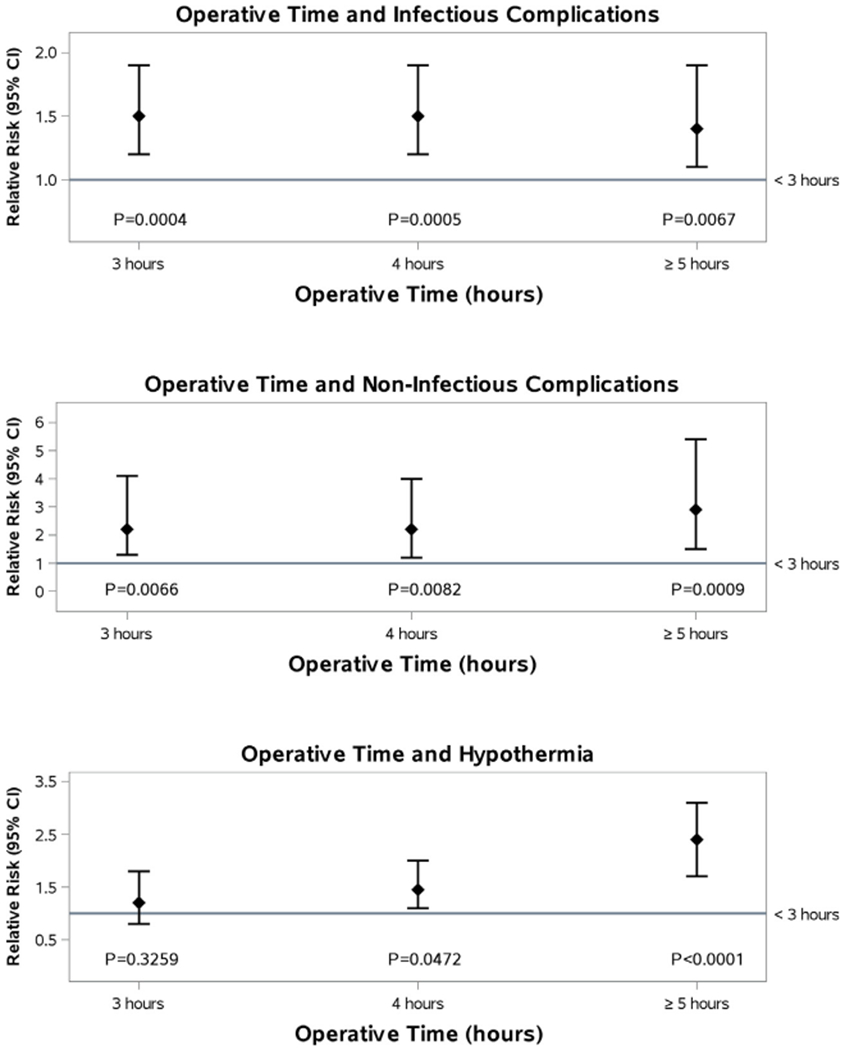

There was an increased risk of infectious complications (sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract and wound infections) for patients who underwent surgeries three hours or more in duration when compared with those undergoing shorter surgeries, with a relative risk of 1.5 (1.2–1.9, p<0.0004) when adjusted for age, burn size, presence of inhalation injury, number of comorbidities, and substance abuse. This association is also true for non-infectious complications, including acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], multi-organ dysfunction syndrome [MODS], and venous thrombo-embolus (including deep venous thrombosis [DVT] and pulmonary embolus [PE]) with a relative risk of 2.3 (1.3–4.1, p<0.0066).

3.2. Study B – operative time and its association with hypothermia

This sub-study included 859 patients; intra-operative temperature data was absent in 124 patients (12.6%). The average age of the patients was 48 years (SD18), they were predominantly male (70%), and had similar TBSA of 12% (5–43). The most common post-operative complications were infectious in nature (specifically, wound, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections). The mortality rate was similar at 5%.

When evaluating the relationship between operative time and hypothermia, we found that surgical duration greater than four hours was associated with the development of hypothermia when compared with the baseline cohort, who underwent surgeries shorter than three hours in duration (p<0.05; Fig. 2) and this remained true when adjusted for age, burn size, presence of inhalation injury, number of co-morbidities, and substance abuse.

Fig. 2 –

Operative time and complications.

3.3. Study C – hypothermia and its association with postoperative complications

The cohort we analyzed in this sub-study was the same data as that in study B above (Table 3). Patients in the hypothermic cohort (≤35°C) had more extensive burn injuries (p<0.0001) and had a greater incidence of inhalation injury (p<0.0001). There were no other statistically significant differences between the two cohorts.

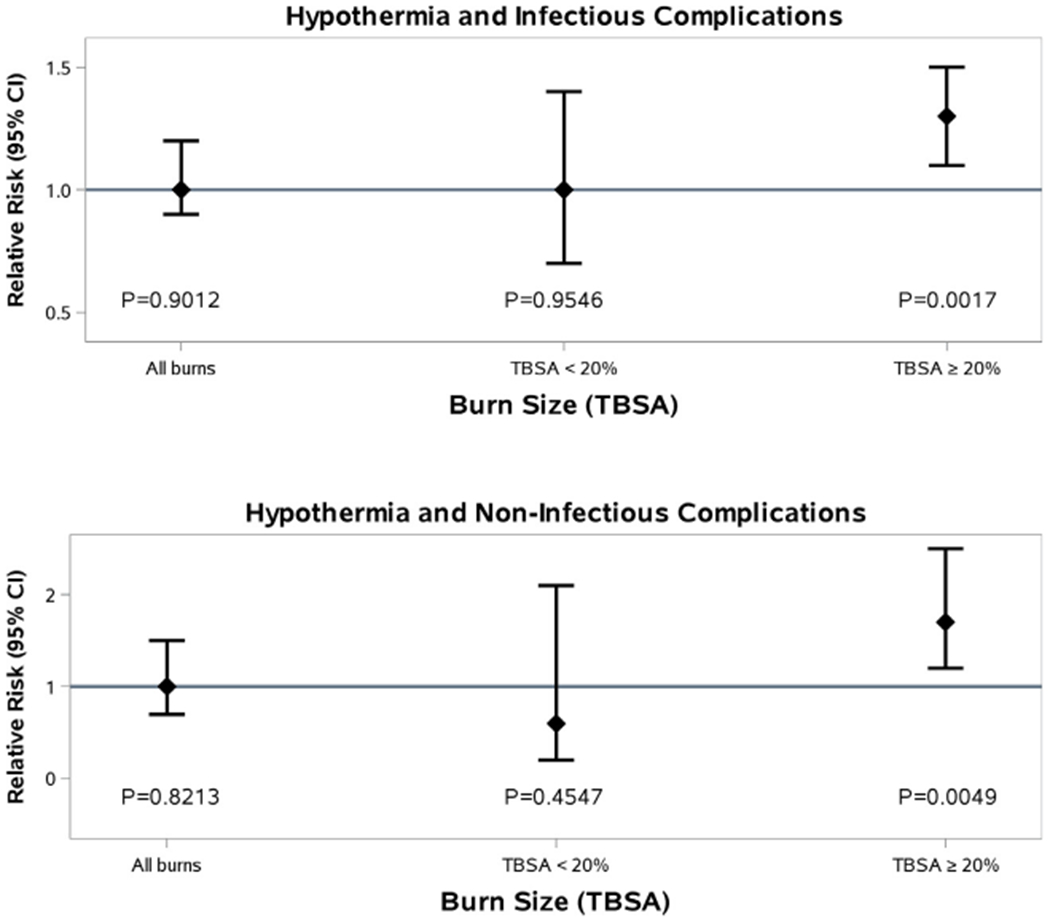

Patients who were hypothermic had higher rates of all complications (except pulmonary embolus) when compared with those who were normothermic (p<0.05), as shown in Table 3. When analyzing the association between hypothermia and complications, there is an increased risk of infectious complications (sepsis, pneumonia, UTI, wound infection) for major burns (over 20% TBSA) with a relative risk of 1.3 (1.1–1.5, p<0.0017) when compared with the normothermic cohorts with major burn injury, after adjusting for age, burn size, presence of inhalation injury, number of co-morbidities, and substance abuse. This association also applies for non-infectious complications (death, ARDS, DVT, PE) with a relative risk of 1.7 (1.2–2.5, p<0.0049; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 –

Hypothermia and complications.

3.4. Study D – a post-hoc risk stratification analysis of operative time and hypothermia on post-operative complications

The patients studied were the same as those in study B and C (Table 3). A total of 859 patients were analyzed to determine the combined effect of operative time and on post-operative complications. Patients with major burns (TBSA≥20%) who became hypothermic intraoperatively, had a significantly higher incidence of death, ARDS, MODS, pneumonia, and urinary tract and wound infections when compared with the normothermic cohort with major burn injury (p<0.05; Table 3).

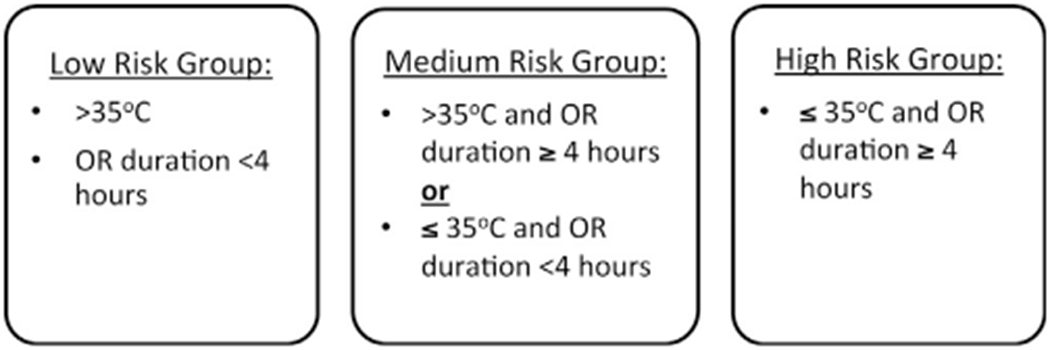

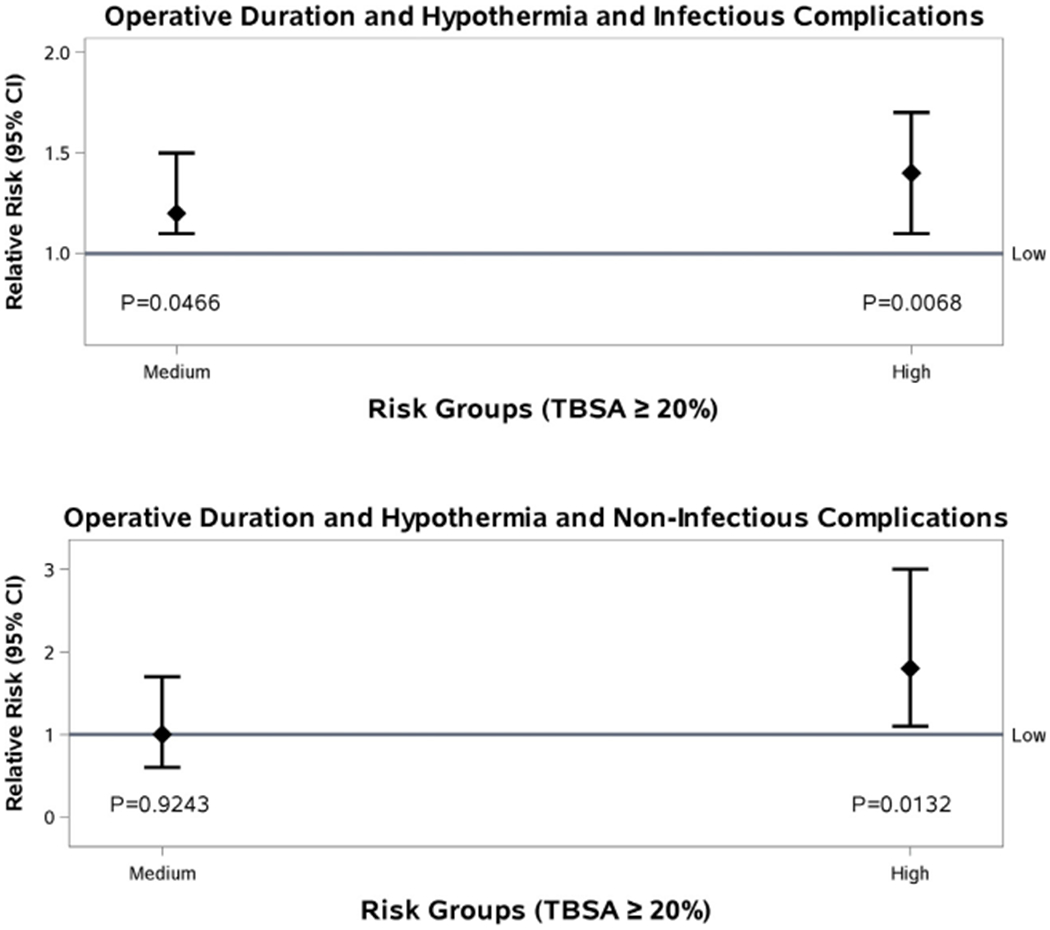

A post-hoc risk stratification analysis of operative time and hypothermia in these patients was undertaken adjusting for age, presence of inhalation injury, number of co-morbidities, and substance abuse. This process divided the patients into three categories consisting of low, medium, and high risk, based on temperature and operative length greater than four hours (Fig. 4). Using these categories, there is an increased risk of infectious complications (sepsis, pneumonia, UTI, would infection) for the high-risk group, with a relative risk of 1.4 (1.1–1.7, <0.0068) when compared with the low risk group. A similar association is observed for non-infectious complications (death, ARDS, DVT, PE), with a relative risk of 1.8 (1.1–3.0, p<0.0132; Fig. 5).

Fig. 4 –

Risk stratification groups.

Fig. 5 –

Operative time and complications, after risk stratification.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that operative length and intraoperative hypothermia are significant risk factors for the development of both infectious and non-infectious complications in the context of acute burn surgery. Detrimental sequelae occur more frequently after four hours of operating time. The presence of inadvertent intraoperative hypothermia was independently associated with increased rates of all postoperative complications in patients with burn injury involving twenty percent or more of the total body surface area. Post hoc analysis, which stratified patients into low, intermediate and high risk groups according to operative time, intraoperative temperature and body surface area, revealed that those patients with major burn injury who undergo prolonged surgeries (over four hours) and develop hypothermia, had significantly increased rates of postoperative complications when compared to the low risk cohort.

While there is considerable literature to support the notion that prolonged operative time and hypothermia compromise the outcomes of patients across the spectrum of surgery [6–11], the findings of this study contribute to the limited literature in the specific context of major burn injury. Burn surgeons are generally well aware of the potential impact and manifestations of hypothermia, and generally apply strategies to prevent or ameliorate this condition, but often in an ad hoc fashion. The practice of staged excisions [5], limiting excisions to maximum body surface areas, or operative time, has generally been applied based on anecdotal experience and convenience, rather than on evidence.

Patients with burn injuries are a subgroup of trauma, but mount a unique inflammatory, hypermetabolic stress response [23–26]. While early surgery has been shown to be of benefit, surgical excision should also be regarded as a form of traumatic insult, a so-called ‘second hit’, exposing susceptible patients to blood loss, coagulopathy, hypothermia, and infection. Hypothermia increases the risk for bleeding by impairing platelet function (reduces thromboxane B2 levels), by compromising temperature dependent enzyme and cytokine function in the coagulation cascade, and by enhancing fibrinolysis, thereby destabilizing clot. Cold also results in a shift in the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve resulting in compromised tissue oxygen delivery. Tissue hypoxia is further exacerbated by catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction. Hypothermia also profoundly alters immune and inflammatory responses by inhibiting the activation of various chemokines and cytokines, and by inducing neutrophil dysfunction. In addition, hypothermia prolongs drug and toxin metabolism and clearance, resulting in delayed recovery from anaesthesia and increased drug side-effects [27].

This plethora of detrimental pathophysiologic effects resulting from hypothermia have the potential to compromise a variety of processes necessary to achieve haemostasis, avoid infection, optimize graft take and wound healing, and ultimately recover from the burn injury. While burn injury per se places susceptible patients at considerable risk of hypothermia, general anaesthesia is also contributory; three phases of hypothermia during anaesthesia have been described, including a body temperature drop of 1–1.5°C during the first hour, a linear decline in temperature from 1 to 3h after induction of general anaesthesia, and a subsequent plateau in core temperature at about 3–4h of anaesthesia. Intraoperative temperature frequently normalizes after several hours in the operating room, assuming that measures are undertaken to ameliorate the development of hypothermia [28].

Written protocols outlining measures to reduce the incidence of intraoperative hypothermia include strategies such as the standard use of warm intravenous and topical fluid solutions, preemptive adjustment of operating room temperatures (between 25 and 35°C), the use of warming devices including blankets, forced-air devices and conductive warming pads, measures to dry or replace soiled moist drapes, and the routine coverage of prepared operative sites not being operated on at that time.

We propose that, in addition to surgical checklists [29] at the beginning and conclusion of major burn cases, hourly ‘check-ins’ or ‘pauses’ be undertaken. This would give the surgeon an opportunity to update nursing staff and the anaesthetic team on the progress of the operation, equipment and instruments that may be required to expedite its effective execution, and the likely duration and blood loss anticipated. The anaesthetist would also be able to formally present the patient’s clinical condition to the rest of the team, and discuss means of addressing any concerns they may have. Surgical checklists in the context of burn injury should always include a discussion about the anticipated operative length, the risk of hypothermia, and proposed preventative strategies. Closer collaboration between the three teams in the operating room, namely the surgeons, nurses, and anaesthetists, has the potential to reduce operative duration and the incidence of hypothermia in susceptible patients.

Preoperative warming is currently being assessed in a quality improvement strategy at this institution, following the discovery that as many as a quarter of patients with major burn injury, at least once during their hospital stay, were hypothermic after induction of anaesthesia but before the initiation of surgery itself. This strategy, also referred to as ‘pre-warming’, has been widely applied in other surgical contexts, but has yet to be broadly applied in the burn surgery context. Although pre-warming should reduce the incidence of hypothermia after induction of anaesthesia, heat loss during sterile skin preparation and draping, evaporative thermal loss from the operative field, and the infusion of cold intravenous fluids can obviously negate these beneficial effects [30,31]. More expeditious and effective methods of preparing the skin surface for operation, while maintaining strict sterile principles, may also contribute to reductions in hypothermia rates.

A limitation of the study included missing intraoperative temperature data for 139 surgeries, which reflects the changing policies and practices at our institution (72% of the missing data occurred during the initial 4 years of period of study). Increasing emphasis on quality improvement and audit has resulted, at least in part, from improved staffing of burn surgeons, and the improved allocation of resources to allow focus on measures to obtain verification with the American Burn Association. In addition, the method of intraoperative temperature measurement was not routinely documented, although nasopharyngeal temperatures were utilized in the majority of cases, except if the face was being operated, in which case rectal temperatures were recorded. Temperatures were recorded by the anaesthetist during the procedure, and a final temperature was entered in the nursing record. Until 2015, only the temperature at the conclusion of the operative case was formally mandated by hospital policy.

The need to adhere to the suggestions derived from this study should not serve to undermine clinical judgment. In the context of debridement and sheet allografting of bilateral dorsal hand burn injuries, for example, 80% of the body surface area can be reliably covered, and additional warming measures applied, for the full duration of the surgery, which may reasonably last well over the prescribed four hours. On the other hand, patients with extensive burn injuries involving several regions of the body, and where skin graft donor sites are also prepared for harvest, will be at considerably greater risk for the sequelae of prolonged surgery and hypothermia. It goes without saying, therefore, that whenever possible, a two team approach should be implemented to optimize operating time, efficacy and patient safety.

It should be noted that the findings from this study derive from practice in the context of an American Burn Association verified burn centre, and specifically in an operating suite dedicated to burn surgery, where strategies to reduce intraoperative hypothermia are routinely applied, and intraoperative temperatures are measured. Most activities of the burn centre are regularly audited and quality improvement and patient safety is a prominent strategic priority. It stands to reason, therefore, that outside of specialist burn centres, the concerns raised in this study, will likely be of even greater importance, and a more critical problem to address.

This study advocates for the restriction of burn surgery, wherever possible, to four hours or less, because operative durations greater than this, especially in the context of major burn injury, are associated with the incidence of hypothermia, as well as increased infectious and non-infectious complications.

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institute of Health (NIH RO1 GM087285-01), Canada Foundation for Innovation Leader’s Opportunity Fund (Project#25407), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Project#123336), Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation-Health Research Grant Program. Funders played no role in study execution.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest relating to the submission entitled ‘The impact of operative time and hypothermia in acute burn surgery’.

REFERENCES

- [1].A WHO plan for burn prevention and care. In: Mock C, Peck M, Peden M, Krug E, editors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jackson DM. The evolution of burn treatment in the last 50 years. Burns 1991;17(August (4))329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Monafo WW, Bessey PQ. Benefits and limitations of burn wound excision. World J Surg 1992;16(Jan-Feb (1)) 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rizzo JA, Rowan MP, Driscoll IR, Chan RK, Chung KK. Perioperative temperature management during burn care. J Burn Care Res 2016(June). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Warden GD, Saffle JR, Kravitz M. A two-stage technique for excision and grafting of burn wounds. J Trauma 1982;22 (February (2))98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lim J, Liew S, Chan H, Jackson T, Burrows S, Edgar DW, et al. Is the length of time in acute burn surgery associated with poorer outcomes? Burns 2014;40(March (2))235–40, doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jurkovich GJ, Greiser WB, Luterman A, Curreri PW. Hypothermia in trauma victims: an ominous predictor of survival. J Trauma 1987;27(September (9))1019–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sagraves SG, Toschlog EA, Rotondo MF. Damage control surgery—the intensivist’s role. J Intensive Care Med 2006;21 (Jan-Feb (1))5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shapiro MB, Jenkins DH, Schwab CW, Rotondo MF. Damage control: collective review. J Trauma 2000;49(November (5))969–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rohrer MJ, Natale AM. Effect of hypothermia on the coagulation cascade. Crit Care Med 1992;20(October (10))1402– 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schmied H, Kurz A, Sessler DI, Kozek S, Reiter A. Mild hypothermia increases blood loss and transfusion requirements during total hip arthroplasty. Lancet 1996;347 (February (8997))289–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sun Z, Honar H, Sessler DI, Dalton JE, Yang D, Panjasawatwong K, et al. Intraoperative core temperature patterns, transfusion requirement, and hospital duration in patients warmed with forced air. Anesthesiology 2015;122(February (2))276–85, doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sessler DI, Kurz A, Lenhardt R. Re: hypothermia reduces resistance to surgical wound infections. Am Surg 1999;65 (December (12))1193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Leaper D, Ousey K. Evidence update on prevention of surgical site infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2015;28(April (2))158–63, doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Offodile AC 2nd, Aherrera A, Wenger J, Rajab TK, Guo L. Impact of increasing operative time on the incidence of early failure and complications following free tissue transfer? A risk factor analysis of 2008 patients from the ACS-NSQIP database. Microsurgery 2015(March), doi: 10.1002/micr.22387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kurz A Thermoregulation in anesthesia and intensive care medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2008;22(December (4))vii–viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Taguchi A, Kurz A. Thermal management of the patient: where does the patient lose and/or gain temperature? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2005;18(December (6))632–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Melfie C, Holleman D, Arthur B. Selecting a patient characteristics index for the prediction of medical outcomes using administrative claims data. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48(7):917–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tortora G, Derrickson B. Principles of anatomy and physiology. Hoboken: Wiley; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Credland N Managing the trauma patient presenting with the lethal triad. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 2016;20:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Abelha FJ, Castro MA, Neves AM, Lendeiro NM, Santos CC. Hypothermia in a surgical intensive care unit. BMC Anesthesiol 2005;5:7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zuo G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159(7):702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Williams FN, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG. The hypermetabolic response to burn injury and interventions to modify this response. Clin Plast Surg 2009;36(October (4))583–96, doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Barret JP, Herndon DN. Modulation of inflammatory and catabolic responses in severely burned children by early burn wound excision in the first 24h. Arch Surg 2003;138(February (2))127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rutan TC, Herndon DN, Van Osten T, Abston S. Metabolic rate alterations in early excision and grafting versus conservative treatment. J Trauma 1986;26(February (2))140–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stratta RJ, Saffle JR, Ninnemann JL, Weber ME, Sullivan JJ, Warden GD. The effect of surgical excision and grafting procedures on postburn lymphocyte suppression. Trauma 1985;25(January (1))46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hart SR, Bordes B, Hart J, Corsion D, Harmon D. Unintended perioperative hypothermia. Ochsner J 2011;11(3):259–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sessler D Temperature monitoring and perioperative thermoregulation. Anaesthesiology 2008;109:318–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hynson JM, Sessler DI, Moayeri A, McGuire BS, Schroeder M. The effects of preinduction temperature and blood pressure during propofol/nitrous oxide anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1993;79:219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vanni SMD, Braz JRC, Modolo NSP, Amorim RB, Rodrigues GR. Preoperative combined with intraoperative skin-surface warming avoids hypothermia caused by general anesthesia and surgery. J Clin Anesth 2003;15:119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Beizat AH, Dellinger EP, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009;360(January (5))491–9, doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119 Epub 2009 January 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]