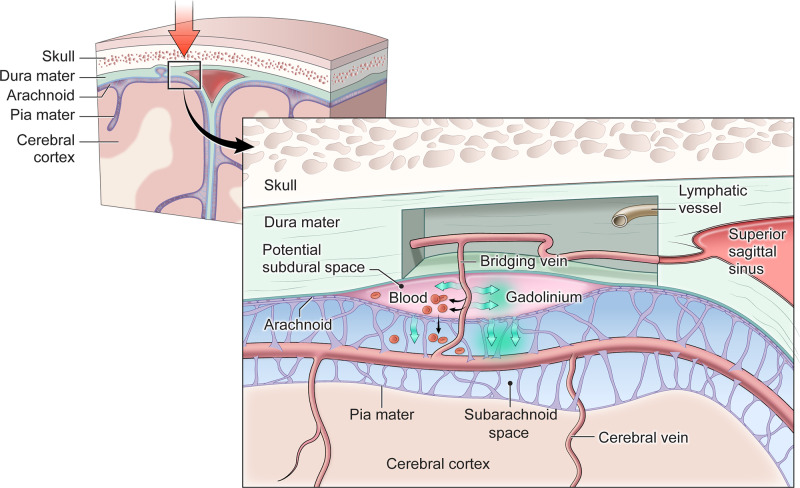

Figure 7.

Conceptual diagram demonstrating how TME and ECSAS might evolve after TBI. The base of the highly vascularized dura mater and the arachnoid lie in close proximity in uninjured meninges. Head trauma (symbolized with a large red arrow) may result in damage that allows either slippage of the dura mater and arachnoid membranes to open a potential subdural space, and/or for bridging veins crossing from the arachnoid space into the dura to be damaged. Subdural haematoma (indicated by red blood cells in the potential subdural space) may result when blood leaking from a damaged bridging vein accumulates in the potential space between the dura and arachnoid. Gadolinium-based contrast agents (indicated by green arrows) can pass through both tears large enough for red blood cells, as well as across smaller areas of damage to get into the potential subdural space, leading to the phenomenon of TME near areas of damaged meninges. In some cases, there may be traumatic damage to the arachnoid membrane itself, with delayed contrast extravasation from the area of TME into adjacent subarachnoid space resulting in the pattern of ECSAS. Damage to the recently discovered meningeal lymphatic vessels, which have been described to be in close association with the dural veins and sinuses, could also be involved the development of TME and/or ECSAS.