Abstract

Aims:

We sought to examine the associations between diabetes self-management, HbA1c, and psychosocial outcomes with the frequency of depressive symptoms.

Methods:

We surveyed 301 teens (50% male, 22% non-white), mean age of 15.0±1.3 years, diabetes duration of 6.5±3.7 years. Biomedical variables: daily frequency of blood glucose monitoring of 4.5±1.9, 63% insulin pump use, mean HbA1c 8.5±1.1% (69±12 mmol/mol); 15% of the sample achieved the target HbA1c of <7.5% (<58 mmol/mol).

Results:

Nearly 1 in 5 (18%, n=54) adolescents reported significant depressive symptoms and, of those participants, slightly under half reported moderate/severe depressive symptoms. Teens with moderate/severe depressive symptoms (CES-D scores ≥24) were more likely to be female, have parents without a college education, and not utilize insulin pumps. Teens with more depressive symptoms reported higher diabetes family conflict, higher diabetes burden, and lower quality of life. In the group reporting no depressive symptoms (10%), scores on psychosocial variables and diabetes treatment variables were the most favorable.

Conclusion:

In our sample, the presence of depressive symptoms appears to relate to both diabetes treatment and quality of life. In addition, studying teens without depressive symptoms can help us learn more about protective factors that potentially buffer against depressive symptoms and that are associated with better outcomes.

Keywords: Adolescence, Type 1 diabetes, Depressive symptoms

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a particularly vulnerable developmental stage for the presence of depressive symptoms that can negatively impact diabetes self-care 1. Further, adolescents with type 1 diabetes demonstrate deteriorating glycemic control due to many biological, psychological, and social challenges 2. Biologically, puberty and hormones make it difficult to accurately dose insulin. Psychologically, adolescents are attempting to assume independence with diabetes management while still developing executive functioning abilities 3. Socially, adolescents strive to be like their peers, and often are not able to make the interruptions necessary to adequately attend to diabetes self-care tasks. Despite facing the adversity of managing a complex and chronic illness, some youth with type 1 diabetes appear to effectively manage these challenges and achieve targeted glycemic control as well as demonstrate high self-reported quality of life 4,5. Recognition of the relationship between depressive symptoms and diabetes self-management in adolescence has led to a burgeoning literature investigating depression and diabetes as well as the potential of protective factors associated with youths’ resiliency 6–14.

Current ADA Standards of Care recommend screening for psychological and diabetes distress 15. Previous publications have generally focused on using depressive symptom cutoff scores to predict group differences related to health outcomes. However, the level of depressive symptom severity may allow for a more nuanced spectrum of depressive symptom categories and may help to discern how these levels may relate to demographic factors, diabetes treatment variables, and psychosocial constructs. In this study, we sought to understand the relationship between diabetes self-management, HbA1c, and psychosocial variables with self-reported depressive symptoms across a range of scores for teens with type 1 diabetes using the CES-D 3-category system (<15, 15–23, and ≥24) for depressive symptom severity as well as the 2-category system of the cutoff score (<15, ≥15). Further, in order to contribute to the literature examining protective factors associated with diabetes resiliency 16–18, we sought to explore the relationship of diabetes self-management behaviors, treatment regimen, HbA1c, and psychosocial variables in the absence of any teen self-reported depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that teens who reported more depressive symptoms would have more negative outcomes in terms of diabetes treatment variables and psychosocial constructs in a large contemporary sample of adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Adolescents with type 1 diabetes, along with a parent or guardian, were recruited during routine clinic visits at 2 large pediatric diabetes clinics. This study entailed an analysis of cross-sectional data from youth with type 1 diabetes and their parents, collected via parent-youth interview, medical record review, and youth and parent surveys. Eligible adolescents were 13–17 years old with a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes for at least 6 months, daily insulin dose of at least .5 U/kg, and an HbA1c of 6.5–11%. Adolescents were excluded if they had a diagnosis of a major psychiatric disorder or had an inpatient psychiatric admission within the past 6 months. A total of 305 teens consented to participate in the study. From the 305 participants, 3 teens withdrew prior to participation and one teen was excluded from analyses after discovery of monogenic diabetes. A final sample of 301 participants and their parents/guardians provided data for analysis. All adolescent and parent participants provided written assent and consent, respectively, prior to any study procedures. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site.

2.2. Data Collection and Measures

Medical chart review and parent/youth interview provided data on diabetes variables. Parents completed a survey to gather information on sociodemographic variables. Blood samples from both sites were analyzed centrally at the Joslin clinical laboratory for measurement of HbA1c (ref. range: 20–42 mmol/mol [4–6%], Roche Cobas Integra, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).Youth completed a survey assessing depressive symptoms. Adolescents and parents completed previously validated psychosocial surveys assessing diabetes adherence, diabetes-specific family conflict, youth and parent diabetes burden, and youth quality of life.

Depressive Symptoms

The major focus of the analyses was on depressive symptoms as measured by the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) 14. The CES-D response options captured how often adolescents experienced a certain symptom in the past week and were based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “rarely or none of the time” to “most or all of the time”. Scores range from 0–60 with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. The most common reported cut point for clinically meaningful depression is 15 or greater 19. If participants scored 15 or higher, parents received notification and were offered counseling resources for their teens. Others have proposed a three category scoring system with 0–15 considered minimal, 16–23 considered mild, and ≥24 considered moderate/severe 20; we also analyzed our sample using this additional higher cut point of ≥24. Finally, we examined a subset of the minimal group that appeared to deny all depressive symptoms with a CES-D score of 0. For these analyses, the 2-category and revised 4-category scoring systems were utilized. In order to examine diabetes self-management, diabetes-specific family conflict, diabetes burden, and general quality of life, we utilized the 2-category as well as 4-category scoring systems for the CES-D to distinguish depressive symptoms on a more granular level.

Diabetes Adherence

Diabetes adherence was assessed using the 20-item Diabetes Management Questionnaire (DMQ) 21, completed by both teens and parents. The scale uses a 5-point Likert scale (“almost never” to “almost always”) to assess perception about how often the teen and/or parent performs various diabetes management tasks over the past month. Total score ranges from 0–100 with higher scores indicating greater degree of adherence.

Diabetes-Specific Family Conflict

Diabetes-specific family conflict was assessed using the 19-item Diabetes Family Conflict Scale (DFC) 22, completed by both teens and parents. Participants and parents rate how often they have had conflict over a management issue within the past month with response options on a 3-point Likert scale (“almost never”, “sometimes”, “almost always”). Total scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating more conflict.

Diabetes Burden

Diabetes burden as perceived by adolescents and their parents was measured by the Problem Areas in Diabetes-Pediatric survey (PAID-Peds) 23 and the Problem Areas in Diabetes-Parent Revised survey (PAID-PR) 24, respectively. The PAID-PR is a self-report of the burden experienced by the parent in raising an adolescent with T1D, not a proxy-report of the parent’s perception of the burden of diabetes on their adolescent. The 20-item PAID-Peds and the 18-item PAID-PR assess burden related to typical problems and issues in diabetes management using a 5-point Likert scale (“Agree” to “Disagree”). Total scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating more burden.

Quality of Life

Generic quality of life was assessed by the 23-item Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Generic Core Scales 4.0 25 which measures the adolescent’s general quality of life by adolescent self-report and parent proxy-report. The PedsQL is scored using a 5-point Likert scale (“Never a problem”, “Almost never a problem”, “Sometimes a problem”, “Often a problem”, and “Almost always a problem”). Total scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics included means, standard deviations, medians, interquartile range, and frequency counts. Pearson correlations assessed associations between teen and parent survey responses. We conducted two sets of analyses; one using the 2-category scoring system of depressive symptoms and one using the 4-category scoring system of depressive symptoms. For the analyses using the 2-category system, unpaired t-tests and chi square tests were used to compare the characteristics of teens with high depressive symptom scores to those with low depressive symptom scores. For the analyses using the 4-category system, ANOVA and Mantel-Haenszel chi square tests were used to compare characteristics across the four levels of depressive symptoms. Due to multiple comparisons being made when comparing the survey results of the 4 different CES-D categories, p was set at <.01 for statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample

The sample (see Table 1) of teens (50% male, 22% non-white) had a mean age of 15.0±1.3 years and diabetes duration of 6.5±3.7 years. The majority of teens (84%) were from 2-parent families and approximately 2/3 (69%) had at least 1 parent with a college education. Most teens practiced intensive insulin therapy; average frequency of blood glucose monitoring was 4.5±1.9 checks/day and 63% received insulin pump therapy. Mean HbA1c was 8.5% ±1.1% (69 ±12 mmol/mol); only 15% of the sample achieved the target HbA1c of <7.5% (<58 mmol/mol). Parent reporters were primarily mothers (83%).

Table 1.

Demographics variables according to self-report depressive symptomatology (2-category)

| Low CES-D <15 n=247 (82%) | High CES-D ≥15 n=54 (18%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14.9 ± 1.3 | 15.2 ± 1.2 | .13 |

| Sex (% male) | 52 | 39 | .09 |

| Race/ethnicity (%non-white) | 21 | 28 | .28 |

| Parent education (% college grad) | 71 | 59 | .10 |

| 2-parent household (%) | 85 | 80 | .29 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 6.6 ± 3.7 | 6.3 ± 4.1 | .65 |

| BG Monitoring (x/day) | 4.6 ± 1.9 | 4.1 ± 2.2 | .08 |

| A1c % (mmol/mol) | 8.5 ± 1.0 (69 ± 11) | 8.7 ± 1.4 (72 ± 15) | .20 |

| Regimen (% pump) | 66 | 48 | .01* |

statistically significant p<.05

3.2. Survey Results

Table 2 presents both youth and parent survey scores. Teen and parent survey scores were significantly, positively correlated: diabetes adherence (r=.42, p<.0001), diabetes-specific family conflict (r=.35, p<.0001), youth quality of life (r=.42 p<.0001), and diabetes burden (r=.28, p<.0001).

Table 2.

Psychosocial constructs according to self-report depressive symptomatology (2-category)

| Low CES-D score (0–14) | High CES-D score (≥15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Teen Report | |||

| Diabetes conflict** | 11 (5–18) | 21 (13–29) | p=.0001* |

| Diabetes burden | 35±21 | 63±22 | p<.0001* |

| Treatment adherence | 71±12 | 66±13 | p=.002* |

| Overall quality of life | 88±9 | 66±13 | p<.0001* |

| Parent report | |||

| Diabetes conflict** | 13 (5–21) | 16 (11–24) | p=.09 |

| Diabetes burden | 42±18 | 48±22 | p=.07 |

| Treatment adherence | 72±13 | 69±14 | p=.15 |

| Overall quality of life | 84±13 | 74±14 | p<.0001* |

statistically significant p < .05

Median & IQR

Depressive Symptoms: Low vs. High (2-category)

In this sample, mean CES-D score was 8.7, range (0–42). The majority (82%) were in the low depressive symptom group with CES-D scores <15. The group with low CES-D scores was compared to the 18% reporting high depressive symptoms (see Table 1.) There were significantly fewer youth with high depressive symptoms using insulin pump therapy as compared to those with low depressive symptoms (48 vs. 66% respectively, p=.01). There were no significant differences between these two groups for any of the other demographic or diabetes treatment characteristics.

Next, we compared psychosocial constructs of those with low depressive symptoms with those with high depressive symptoms (see Table 2.) There were substantial differences in teen report of psychosocial variables. Adolescents with high depressive symptoms had significantly more teen-reported diabetes family conflict (p=.0001), more diabetes burden (p<.0001), lower diabetes adherence (p=.002), and poorer quality of life (p<.0001). Parent proxy report of teen quality of life was also lower in teens with high depressive symptoms as opposed to those with low depressive symptoms (p<.0001).

Depressive Symptoms: Absent, Minimal, Mild, Moderate/Severe (4-category)

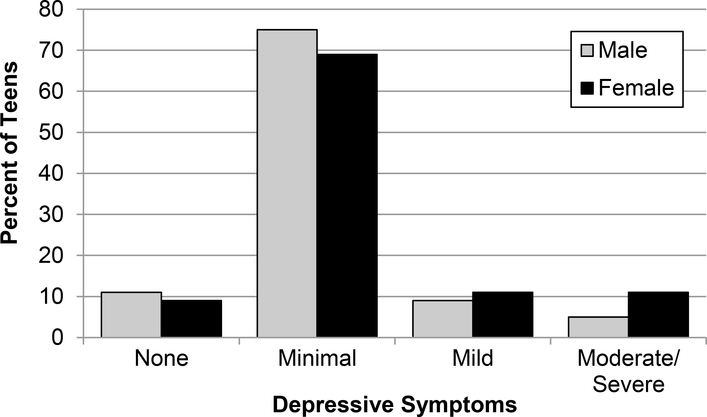

For the analysis of the four categories of depressive symptoms, 10% of adolescents scored zero, (indicating the absence of self-reported depressive symptoms), 72% scored in the 1–14 range (indicating minimal depressive symptoms), 10% scored in the range of 15–23 (indicating mild depressive symptoms), and 8% scored 24 or above (indicating moderate/severe depressive symptoms). Figure 1 displays depressive symptoms severity group according to sex.

Figure 1.

Frequency of depressive symptoms by sex

There were significant differences across the 4 depressive symptom categories for some demographic variables. There was a significant difference in proportions of males to females among the four different groups with a greater proportion of females who reported a higher number of depressive symptoms (X2 = 4.0, df=1, p=.05). Among teens reporting moderate/severe depressive symptoms, 42% of their parents had attained a college education compared to the 69–81% reported in the other three categories (p=.007). In addition, average HbA1c among those reporting moderate/severe depressive symptoms was 9.2% compared to the 8.3%−8.5% in the three other categories (p=.01). Pump use also showed significant variation among the four groups (X2=6.2, df=1, p=.01) with fewer adolescents using an insulin pump as depressive symptoms increased. There were no other significant differences among the demographic variables between the groups.

Psychosocial Variables

For the psychosocial survey results, diabetes treatment adherence was not found to be significantly different among the four depressive symptom categories for either parent report or teen report. Youth report of diabetes-specific family conflict was found to have significant variation among the four categories (x2 (3) =21.4, p<.0001); however, parent report of diabetes-specific family conflict was not significantly different across groups. Adolescents with moderate/severe (≥24) depressive symptoms reported significantly more conflict than teens in the absent depressive symptoms group (z=3.94, p<.0001) and teens in the minimal depressive symptoms group (1–14) (z=3.33, p=.0009). In addition, teens with mild depressive symptoms (15–23) had more conflict than teens with no depressive symptoms (z=2.96, p=.003). Teen report of diabetes related burden was found to have significant variation among the four categories [F (3, 297) = 35.68, p<.0001]. Depression categories of increasing severity were significantly different from one another for youth reported diabetes burden (see table 3), such that burden increased as the degree of depressive symptoms increased. Parent reported diabetes burden was also found to have significant variation among the categories. Parents of teens who reported moderate/severe depressive symptoms (≥ 24) had significantly higher diabetes burden than those who reported zero depressive symptoms (F= 9.96, p= .002), those who reported minimal depressive symptoms (1–14) (F = 16.30, p <.0001), and those who reported mild depressive symptoms (15–23) (F = 13.11, p=.0003). Teen reported quality of life was found to have significant variation among the four categories [F (3, 297) = 105.20, p<.0001]. Every depression category was significantly different from one another for quality of life (see table 3), such that quality of life decreased as frequency of depressive symptoms increased. Parent-reported quality of life was found to have significant variation among the categories. Parents of teens in the absent depressive symptoms group reported significantly better quality of life than parents of adolescents with minimal depressive symptoms (1–14) (F= 8.52, p=.004), those with mild depressive symptoms (15–23) (F=13.98, p=.0002), and those with moderate/severe depressive symptoms (≥24) (F= 35.36, p<.0001). In addition, parents of teens with moderate/severe depressive symptoms (≥ 24) reported that their teen had significantly poorer quality of life than parents of teens with minimal depressive symptoms (1–14) (F=24.08, p<.0001).

Table 3.

Demographic variables according to self-report depressive symptomatology (4-category)

| CES-D score =0 n=31 (10%) | CES-D score 1–14 n=216 (72%) | CES-D score 15–23 n=30 (10%) | CES-D score ≥ 24 n=24 (8%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15.2 ± 1.4 | 14.9 ± 1.3 | 15.3 ± 1.2 | 15.2 ± 1.3 | .30 |

| Sex (% male) | 55 | 51 | 47 | 29 | .05 |

| Race/ethnicity (% non-white) | 16 | 22 | 23 | 33 | .14 |

| Parent education (% college grad) | 81 | 69 | 73 | 42 | .007* |

| 2-parent household (%) | 84 | 86 | 80 | 79 | .41 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 7.8 ± 3.9 | 6.4 ± 3.6 | 6.5 ± 4.3 | 6.2 ± 3.8 | .23 |

| BG Monitoring (x/day) | 4.7±1.8 | 4.6±1.9 | 4.0±1.7 | 4.2±2.6 | .36 |

| A1c % (mmol/mol) | 8.3 ± 0.9 (67 ± 10) | 8.5 ± 1.0 (69 ± 11) | 8.4 ± 1.2 (68 ± 13) | 9.2 ± 1.5 (77 ± 16) | .01* |

| Regimen (% pump) | 68 | 66 | 53 | 42 | .01* |

Statistically significant, p < .05

The 10% of adolescents who reported no depressive symptoms demonstrated many positive characteristics (see Table 3 & 4). Survey scores for both teens and parents were the most favorable, especially regarding both youth and parent proxy report for quality of life, as well as lowest reports of diabetes-specific family conflict and diabetes burden, and highest report of treatment adherence.

Table 4.

Psychosocial constructs according to self-report depressive symptomatology (4-category)

| No Depressive Symptoms (n=31) 10% | Minimal Depressive Symptoms (n=216) 72% | Mild Depressive Symptoms (n=30) 10% | Moderate/Severe Depressive Symptoms (n=24) 8% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teen Report | |||||

| Diabetes conflict** | 5 (3–13) | 11 (5–21) | 20 (8–32) | 21 (16–28) | P<.0001 |

| Diabetes burden | 24±18 | 36±21 | 55±22 | 74±18 | p<.0001 |

| Treatment adherence | 73±13 | 71±12 | 65±12 | 67±15 | p=.02 |

| Overall quality of life | 96±4 | 87±9 | 73±9 | 58±13 | p<.0001 |

| Parent Report | |||||

| Diabetes conflict** | 11 (0–16) | 13 (8–21) | 15 (8–21) | 18 (12–24) | p=.01 |

| Diabetes burden | 43±16 | 42±19 | 40±19 | 59±22 | p=.0007 |

| Treatment adherence | 73±16 | 71±13 | 68±14 | 70±14 | P=.38 |

| Overall quality of life | 90±11 | 83±12 | 78±13 | 70±14 | p<.0001 |

Statistically Significant p < .01

Median & IQR

4. Discussion

The current study investigates relative rates of depressive symptoms in a contemporary sample of adolescents with type 1 diabetes from two sites in the United States and evaluates two potential scoring systems for clinical cut-points in this sample. Our sample included a relatively diverse population with 22% of the youth identifying as non-white and 69% of families having at least one parent with a college education. Nearly 1 in 5 (18%) adolescents reported significant depressive symptoms (10% with mild depressive symptoms, 8% with moderate/severe depressive symptoms), which highlights the importance of evaluating depressive symptoms in teens with diabetes. Furthermore, given the demanding nature of type 1 diabetes management, it is important to provide support to lessen the burden of diabetes management for those experiencing depressive symptoms.

The average CES-D score for this sample was 8.7, which is comparable to the score of 9.7 reported in the SEARCH study of adolescents with type 1 diabetes 1. These values are lower than 12.2, which was the average score on the CES-D in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health 20. However, in our sample, we excluded any participants with major psychiatric illness as well as participants with an HbA1c >11%, which may account for the lower rate of depressive symptoms. We utilized a 4-category system which has many advantages. The first is that having a more nuanced spectrum of depressive symptom categories may help to discern how these levels may relate to demographic, diabetes treatment variables, and psychosocial constructs. These categories may help tailor interventions to the range of depressive symptoms found in teens with T1D as well as help allocate scarce mental health resources to those teens who are in the highest need. Additionally, having a category of teens identified with no depressive symptoms highlights the sensitivity of this measure at both ends of the spectrum, such that those with no depressive symptoms continued to demonstrate more beneficial outcomes than those with minimal and mild symptoms.

When comparing those teens with no depressive symptoms to those with depressive symptoms, we found certain demographic, biomedical, and psychosocial characteristics were associated with depressive symptoms. Those with moderate/severe depressive symptoms (CES-D scores ≥24) were more likely to be female and have parents without a college education. This observation aligns with the general adolescent literature on depression as well as the literature on depressive symptoms in youth with type 1 diabetes 1,20,26. Adolescent females are more likely to experience depressive symptoms and this greater vulnerability needs to be considered when designing interventions.

With respect to diabetes self-management characteristics, insulin pump use was underrepresented in those reporting depressive symptoms, with groups with higher scores reporting lower insulin pump use. However, the cross-sectional nature of this study only allows for associations rather than causality assessment; it is plausible that adolescents who experience depressive symptoms may be too burdened or stressed to use advanced diabetes technology. Additionally, prescribers may be less likely to initiate pump therapy or may discontinue pump therapy when teens are reporting more depressive symptoms. Further longitudinal investigation is required to test this relationship. The biomedical characteristic, HbA1c, was also higher in teens reporting moderate/severe depressive symptoms compared with the other groups, indicating teens in the group reporting the most depressive symptoms are also experiencing the worst glycemic control.

With respect to psychosocial characteristics, adolescent self-report of depressive symptoms was associated with other markers of psychological well-being and diabetes-specific psychosocial constructs. Teens with more depressive symptoms reported more diabetes-specific family conflict, more diabetes burden, and poorer quality of life. Parental report of teen quality of life was also associated with more depressive symptoms. The 4-category analysis of depressive symptoms demonstrated that those teens reporting moderate/severe depressive symptoms have more parent-report diabetes related burden than the other three depressive symptom categories.

In the group reporting no depressive symptoms (10%), scores on the other psychosocial variables and diabetes treatment variables were the most favorable. Adolescents who reported no depression had the most favorable self-report scores on diabetes-specific family conflict, diabetes burden, diabetes adherence, and quality of life. One might consider that the adolescents were only providing socially desirable responses. However, scores from parent report about their teens were also the most favorable with the exception of parent-reported diabetes-related burden which speaks to the parent’s experience and not the teen. And although not statistically significant, these teens had the lowest mean HbA1c of all four groups and demonstrated the highest level of self-management as measured by self-report number of blood glucose checks. Indeed, this group of adolescents with type 1 diabetes and no reported depressive symptoms may be unencumbered by mood issues and/or have had the opportunity to develop attitudes, strengths, and skills to help cope with managing diabetes during adolescence.

There are several limitations of the study that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, this is a cross-sectional, observational study, and so causality cannot be inferred. Second, the assessment of depressive symptoms involved a self-report questionnaire that can be prone to socially desirable responses as noted above. However, we took the following precautions to encourage honest responses, informed the teen that only the study staff will see their responses and had the teen complete questionnaires independent from parents. Assessment of psychopathology (i.e., depressive disorder) could be strengthened by an objective structured clinical diagnostic interview such as the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) in future research 27 to examine factors associated with a diagnosable disorder. In addition, we are unaware of validated efforts to look at scores of zero on the CES-D but we were struck by how individuals who denied depressive symptoms demonstrated different biomedical and psychosocial characteristics. More research is needed on this population and their adjustment to type 1 diabetes. Lastly, the current study included predominantly Caucasian teens from 2-parent highly educated families, limiting generalizability, however, 22% of the teens represented racial and ethnic minority groups, a proportion higher than many studies of youth with type 1 diabetes.

In conclusion, the presence of depressive symptoms in teens with type 1 diabetes appears to relate to both diabetes self-management, diabetes-specific family conflict, and general quality of life. Using the four category depressive symptom system allows for screening and intervention efforts to be more targeted as well as exploration into protective factors associated with diabetes resiliency.

Highlights:

Parent-report data on psychosocial measures was obtained.

The CES-D category system for depressive symptom severity (0, <15, 15–23, ≥24) as well as the cutoff score (<15, ≥15) was used to examine associations with diabetes self-management, HbA1c, and psychosocial variables and depressive symptoms.

Results provide understanding of those most affected by depressive symptoms and future research directions in resiliency.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by NIH grants R01DK095273, K12DK09472, and P30DK036836, JDRF grant 2-SRA-2014-253-M-B, the Katherine Adler Astrove Youth Education Fund, the Maria Griffin Drury Pediatric Fund, and the Eleanor Chesterman Beatson Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these organizations. The study sponsors were not involved in designing the study; collecting, analyzing, or interpreting the data; writing the manuscript; or deciding to submit the manuscript for publication. Portions of this manuscript were presented as an abstract at the 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, June 5–9, 2015, Boston, MA.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement:

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this research. None of the authors received any form of payment to produce the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

☒ The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lawrence JM, Standiford DA, Loots B, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressed mood among youth with diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1348–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron FJ, Wherrett DK. Care of diabetes in children and adolescents: controversies, changes, and consensus. Lancet. 2015;385(9982):2096–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez KM, Patel NJ, Lord JH, et al. Executive Function in Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: Relationship to Adherence, Glycemic Control, and Psychosocial Outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(6):636–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson BJ, Laffel LM, Domenger C, et al. Factors Associated With Diabetes-Specific Health-Related Quality of Life in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes: The Global TEENs Study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(8):1002–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. State of Type 1 Diabetes Management and Outcomes from the T1D Exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21(2):66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hood KK, Rausch JR, Dolan LM. Depressive symptoms predict change in glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: rates, magnitude, and moderators of change. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12(8):718–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hood KK, Lawrence JM, Anderson A, et al. Metabolic and inflammatory links to depression in youth with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2443–2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence JM, Yi-Frazier JP, Black MH, et al. Demographic and clinical correlates of diabetes-related quality of life among youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr 2012;161(2):201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colton PA, Olmsted MP, Daneman D, Rodin GM. Depression, disturbed eating behavior, and metabolic control in teenage girls with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2013;14(5):372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corathers SD, Kichler J, Jones NH, et al. Improving depression screening for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1395–e1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hood KK, Beavers DP, Yi-Frazier J, et al. Psychosocial burden and glycemic control during the first 6 years of diabetes: results from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(4):498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zdunczyk B, Sendela J, Szypowska A. High prevalence of depressive symptoms in well-controlled adolescents with type 1 diabetes treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2014;30(4):333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGill DE, Volkening LK, Pober DM, Muir AB, Young-Hyman DL, Laffel LM. Depressive Symptoms at Critical Times in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes: Following Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis and Insulin Pump Initiation. J Adolesc Health. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 15.13. Children and Adolescents: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Supplement 1):S148–S164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iturralde E, Hood KK, Weissberg-Benchell J, Anderson BJ, Hilliard ME. Assessing strengths of children with type 1 diabetes: Validation of the Diabetes Strengths and Resilience (DSTAR) measure for ages 9 to 13. Pediatr Diabetes. 2019;20(7):1007–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilliard ME, Hagger V, Hendrieckx C, et al. Strengths, Risk Factors, and Resilient Outcomes in Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: Results From Diabetes MILES Youth-Australia. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(7):849–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monaghan M, Clary L, Stern A, Hilliard ME, Streisand R. Protective Factors in Young Children With Type 1 Diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol 2015;40(9):878–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Screening for adolescent depression: a comparison of depression scales. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(1):58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rushton JL, Forcier M, Schectman RM. Epidemiology of depressive symptoms in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta SN, Nansel TR, Volkening LK, Butler DA, Haynie DL, Laffel LM. Validation of a contemporary adherence measure for children with Type 1 diabetes: the Diabetes Management Questionnaire. Diabet Med. 2015;32(9):1232–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hood KK, Butler DA, Anderson BJ, Laffel LMB. Updated and revised Diabetes Family Conflict Scale. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(7):1764–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz JT, Volkening LK, Butler DA, Laffel LM. Youth-perceived burden of type 1 diabetes: Problem Areas in Diabetes survey-Pediatric version (PAID-Peds). J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015;9(5):1080–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markowitz JT, Volkening LK, Butler DA, Antisdel-Lomaglio J, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM. Re-examining a measure of diabetes-related burden in parents of young people with Type 1 diabetes: the Problem Areas in Diabetes Survey - Parent Revised version (PAID-PR). Diabet Med 2012;29(4):526–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39(8):800–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1056–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]