The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic altered how clinicians care for patients. Ophthalmologists saw an estimated 81% drop in volume, the most of any specialty during the initial pandemic and public health restrictions.1 Concurrently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed many of the regulatory restrictions (i.e., rural designation zones) on telehealth and began to reimburse for professional telehealth services at the same rates as in-person visits, with the goal of increasing patient access to care via synchronous methods of telehealth such as virtual visits.2 Ophthalmologists may have difficulty with telehealth visits because much of the evaluation requires a slit lamp, tonometer, dilation, and advanced imaging such as OCT.

Evidence of the proportion of actual ophthalmic telehealth use volume beyond a single institution is lacking. Potential trends, such as the reduction in the use of telehealth after an initial surge or the use of telehealth more prominently by certain subspecialties within ophthalmology, are not confirmed with primary data. Our study is the first to demonstrate the characteristics of telehealth use in ophthalmology on a large scale with primary data before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study was deemed “not regulated” by the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board, and the study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

We used Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan claims data to identify ophthalmology encounters using a local specialty code, including all outpatient and professional fee claims from September 1, 2019, through September 1, 2020. A synchronous telehealth encounter was defined by the presence of specific procedure modifier codes (25 or GT). Store-and-forward retinal imaging claims (Current Procedural Terminology codes 92227 and 92228) were added to the analysis separately. Postoperative visits within the global postoperative period were not included because they are not billed regularly. Current Procedural Terminology code 99024 (postoperative follow-up visit) accounted for only 0.006% of total ophthalmologist claims in 2019 and 2020. Two proportion Z tests were completed for determining differences between telehealth use rates (P < 0.001 was considered statistically significant).

The most frequent 100 overall primary diagnosis codes and most frequent 100 telehealth primary diagnosis codes were determined after the onset of the state of Michigan stay-at-home order on March 24, 2020. Diagnoses were grouped into 13 subspecialty categories in accordance with diagnostic groups defined by the Clinical Classification Software, an organizational system developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (Table S1, available at www.aaojournal.org).

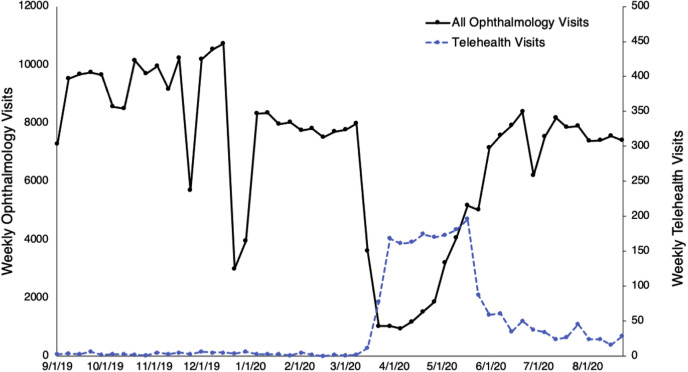

A total of 362 355 ophthalmology visits occurred from September 1, 2019, through September 1, 2020. Telehealth visits accounted for 91 of the 235 327 ophthalmic visits (0.04%) from September 1, 2019, through March 14, 2020, and 2031 of the 127 028 ophthalmic visits (1.6%) from March 15, 2020, through September 1, 2020 (P < 0.001). The proportion of telehealth visits peaked at 17.0% of ophthalmic visits (4/5/20–4/11/20; Fig 1 ). A maximum of 84 (30%) ophthalmologists used telehealth (3/29/20—4/4/20). By September 2020, 228 of 610 ophthalmologists (37.4%) had used telehealth.

Figure 1.

Line graph showing weekly ophthalmology visits by total visits and telehealth visits from September 1, 2019, through September 1, 2020. Over the course of the full period, telehealth accounted for 0.58% of total ophthalmic visits: 0.04% from September 1, 2019, through March 15, 2020, and 1.6% from March 24, 2020, through September 1, 2020. Total telehealth use peaked from March 29, 2020, through May 23, 2020. The minimum number of total ophthalmology visits occurred from March 29, 2020, through April 11, 2020. At its peak, telehealth accounted for 17.0% of total ophthalmology visits.

Chalazia, the most common telehealth diagnosis, accounted for 9.4% of telehealth claims. Dry eye disease (4.8%), conjunctival hemorrhage (2.1%), allergic conjunctivitis (1.9%), unspecified blepharitis (1.9%), and squamous blepharitis (1.3%) also were top 10 telehealth diagnoses categorized as cornea and external disease. Moderate primary open-angle glaucoma (2.8%), exudative age-related macular degeneration (2.2%), preglaucoma (1.3%), and mild primary open-angle glaucoma (1.3%) also were commonly used diagnoses (Table S2, available at www.aaojournal.org).

Cornea and external disease conditions accounted for 48.0% of the telehealth visits and 13.2% of in-person visits (P < 0.001). Retina and vitreous conditions and glaucoma accounted for 16.8% and 13.4% of telehealth visits, respectively, but 38.6% (P < 0.001) and 23.8% (P < 0.001) of in-person visits, respectively. Cataract and other lens disorders accounted for 3.1% of telehealth claims and 17.0% of in-person claims (P < 0.001). No difference was found for strabismus (P = 0.407) and neuro-ophthalmology (P = 0.002) conditions (Table S3, available at www.aaojournal.org).

Our study identified the rapid increase and subsequent decrease in the use of telehealth by ophthalmologists during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic and low levels of teleophthalmology use overall. Ophthalmology has been reported as the discipline with the lowest number of users of telehealth.3 , 4 Cornea and external diseases accounted for a significantly greater proportion of telehealth visits than they did for total visits, whereas retina and vitreous conditions, glaucoma, and cataract and other lens disorders constituted fewer telehealth evaluations.

Currently, conditions associated with corneal and external pathologic features are assessed best via telehealth, and use for these conditions may reduce in-person visits. Expansion of technology such as home tonometry and home OCT (which already have been developed) and further home-based innovation may allow for increased adoption of virtual visits for glaucoma and retina care, especially for established patients.5 , 6 Ophthalmology previously focused on asynchronous forms of telehealth, such as store-and-forward imaging to address workforce shortages, not to reduce in-person visits.7 Our study found that ophthalmologists were not well equipped to shift care from clinics to patients’ homes. A key limitation was the inclusion of data from only one payer (Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan) in only one state (Michigan).

The increase in telehealth adoption coincided with both the pandemic and new federal rules on telehealth. Each factor confounds the other as far as causality for the increase in ophthalmic telehealth. However, the percentage of telehealth use declined after April 11, 2020, whereas the COVID-19 pandemic and equivalent reimbursements continued. The decline likely is related to the need for in-person examination and imaging to assess patients accurately. Various procedures and higher-level office visits typically are not feasible, creating a financial disincentive to continue telehealth visits along with the ethical, patient safety, and legal ramifications of an incomplete or inadequate evaluation. These challenges also must be balanced with patient perceptions of efficacy and convenience. Existing technology such as a home tonometry or home OCT could allow for more effective and frequent use of virtual visits. Until such technology is reimbursed and used further, patients with symptoms indicative of chalazia, blepharitis, conjunctival hemorrhage, and dry eye may benefit from an initial telehealth evaluation to reduce in-person visits.

Footnotes

Disclosure(s): All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The author(s) have made the following disclosure(s): R.P.: Consultant – Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield

Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no.: K08 HS027632-01 [C.E.]); the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (grant no.: R01EY031033 [M.A.W.]); Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan, Detroit, Michigan (M.A.W.); and Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, New York (M.A.W.).

HUMAN SUBJECTS: No human subjects were included in this study. This study was deemed “not regulated” by the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board, and the study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

No animal subjects were included in this study.

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: Portney, Zhu, Ellimoottil, Parikh

Analysis and interpretation: Portney, Zhu, Chen, Ellimoottil, Parikh

Data collection: Portney, Zhu, Steppe, Ellimoottil, Parikh

Obtained funding: Woodward, Ellimoottil; Study was performed as part of the authors' regular employment duties. No additional funding was provided.

Overall responsibility: Portney, Zhu, Chen, Steppe, Chilakamarri, Woodward, Ellimoottil, Parikh

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Strata Decision Technology Analysis: ophthalmology lost more patient volume due to COVID-19 than any other specialty. Eyewire News. 2020. https://eyewire.news/articles/analysis-55-percent-fewer-americans-sought-hospital-care-in-march-april-due-to-covid-19/ Accessed 03.11.20.

- 2.Centers Medicare and Medicaid Services Telehealth: Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet Accessed 04.11.20.

- 3.Aguwa U.T., Aguwa C.J., Repka M. Teleophthalmology in the era of COVID-19: characteristics of early adopters at a large academic institution. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(7):739–746. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehrotra A., Chernew M., Linetsky D., et al. Impact COVID outpatient care: visits prepandemic levels but not all. 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/oct/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-care-visits-return-prepandemic-levels Accessed 21.11.20.

- 5.Liu J., De Francesco T., Schlenker M., Ahmed I.I. Icare home tonometer: a review of characteristics and clinical utility. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:4031–4045. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S284844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galiero R., Pafundi P.C., Nevola R. The importance of telemedicine during COVID-19 pandemic: a focus on diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Res. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/9036847. 2020:9036847. Oct 14, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rathi S., Tsui E., Mehta N. The current state of teleophthalmology in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(12):1729–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.