Abstract

The need to develop interest in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) skills in young pupils has driven many educational systems to include STEM as a subject in primary schools. In this work, a science kit aimed at children from 8 to 14 years old is presented as a support platform for an innovative and stimulating approach to STEM learning. The peculiar design of the kit, based on modular components, is aimed to help develop a multitude of skills in the young students, dividing the learning process into two phases. During phase 1 the pupils build the experimental setup and visualize the scientific phenomena, while in phase 2, they are introduced and challenged to understand the principles on which these phenomena are based, guided by a handbook. This approach aims at making the experience more inclusive, stimulating the interest and passion of the pupils for scientific subjects.

Keywords: Hands-on Learning, Elementary/Middle School Science, Multidisciplinary, STEM Subject, 3D Printing

Introduction

Our society is more and more dependent on technology and engineering; however, there is a profound lack of understanding of the basic principles of most of these technologies by a majority of the population.1 In the early 2000s, scientists started noticing that in the USA there was an incongruence between the job market demands and the distribution of college graduates across different fields of studies.2 This phenomenon was not a problem in the USA alone. Many reports in the 2000s and 2010s showed that science and mathematics education in postcompulsory years of schooling was also dramatically declining in Australia3,4 and Europe,5 while the demand for the application of STEM skills was rapidly increasing.6 In the same period, the term STEM subject was introduced: an acronym for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. The idea behind STEM was to create a subject that would give the students an integrated course, focused on skills that are required in today’s job market, rather than letting them learn fragmented bits of knowledge. The development of high-level STEM skills is reliant on an early-age onset of interest and passion for scientific subjects. Primary education has a crucial role in this regard. In 2012, the PISA survey (Programme for International Student Assessment, promoted by OCSE) showed that, in the European Union, 18% of the pupils had low-level science skills, in line with the USA but much higher in comparison with 7% for Korea and 8% for Japan. To address these problems, many different initiatives have been launched, both nationally and internationally. One such branch of initiatives included the development of new pedagogical approaches to STEM, focusing especially on the link between experience and classroom.7−9 The idea is that young students should be engaged in the learning process, making STEM lessons more enjoyable. Hand in hand with this evolution of the teaching methods, a multitude of supporting materials were developed. In the past decade, many scientific kits appeared on the market: affordable platforms focused on a scientific subject that allow pupils to learn in a fun and entertaining way. These kits are mainly focused on children of ages between 8 and 14, in order to be usable in both primary and secondary school classrooms,10 as well as at home as entertaining tools. The STEM kits are generally focused on one of the following subjects: chemistry, simple electronics and coding, physics and engineering, biology, and life sciences. While these kits provide a valid platform to engage the pupils and stimulate in an early phase their interest and passion for science, they are focused on one specific subject. To address this issue, we designed an educational toy made up of modular blocks that allows the creation of a multitude of different scientific experiments in various STEM fields. As shown in the literature, 3D printing is playing an important role not only in the research environment11 but also in the field of education, providing new tools for novel teaching methods.12−14 In these examples, the authors exploit the advantages that 3D printing offers, mainly versatility and cost efficiency, to develop all kinds of ideas that could have a benefit for the learning process of students.15 One of the fields where such tools are employed is chemistry, with examples ranging from a simple visualization of concepts (3D printed models of molecules and proteins)16,17 to more complex examples such as the fabrication of Ag/AgCl reference electrodes.18 Also developed thanks to 3D printing, our scientific kit features individual building blocks that have internal fluidic channels, making it possible to create a connected system by combining different blocks. This allows a child to flush liquids through the system: we designed scientific experiments that can be performed inside such created connected structures. Thanks to the modular approach, it is possible to develop many different experiments, exploring a broad range of scientific phenomena. Our aim is to let children play in the first place and, along the way, get passionate about science and ultimately discover properties and procedures of scientific experiments.

Materials and Hazards

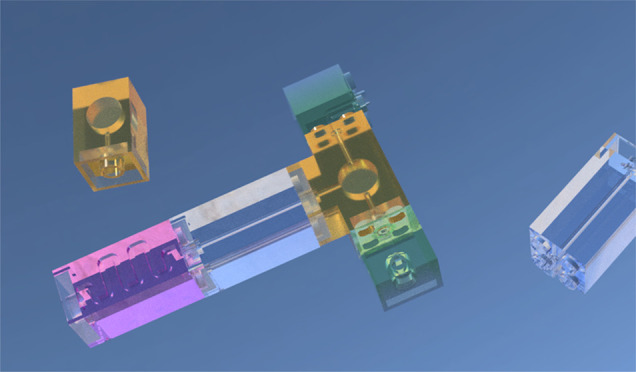

The kit is composed of modular transparent building blocks (see Figure 1), inspired by Lego bricks.

Figure 1.

Science toy kit: (A) coiled channels; (B) droplet generator; (C) straight channels; (D) 90° turn and T junction; (E) mixing and visualization chamber; (F) all of the blocks together on a Lego mat; (G) picture of the Poseidon pumps used.

The classic design with circular features was replicated, allowing for vertical interconnection of the blocks. In addition, to allow the creation of a “fluidic circuit”, a second type of connection has been developed: an axial link (see Figure 1) between two adjacent blocks that allows connecting the outlet of one block to the inlet of the second block. In such a way, the blocks can be modularly combined to create a fluidic channel. Furthermore, standard Lego bricks can be used in combination with the kit, to build supporting structures (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

“Fruit caviar” experiment. From left to right: layout of the experiment with the modular blocks assembled and placed on the supporting mat; schematic of the assembly that the children have to build in order to perform the experiment; final results of the experiment, with the colored alginate droplets created in the reservoir section.

The kit is made out of eight different types of blocks, divided into functionalized and nonfunctionalized parts. Functionalized parts are those that feature geometries and design features which allow the creation and visualization of a specific scientific phenomenon. Functionalized parts are mixing chambers, droplet generators, and reservoirs. Nonfunctionalized parts are blocks that are used to complete the fluidic circuit: straight channels, coiled channels, 90° turns, T junctions, and connectors for tubing. Each kit is also provided with a set of pumps that allow control of the flow rates inside the fluidic circuit (see Figure 1). The pumps are based on an open access model.19 A simple software (Appendix 2) is used to control the pumps through an intuitive user interface. The bricks are designed with Fusion 360 (Autodesk) and printed with a commercially available desktop 3D printer (Form2, Formlabs). On the basis of previous studies,20 we selected Clear resin V5 (Formlabs) as the material, thanks to its transparency characteristics and reliability in printing. For the current study, three examples of experiments have been developed and tested. All of the experiments can be performed with nontoxic, nonharmful and easily available materials. For the set of experiments presented in this study, on top of the supplied science kit, the following items are necessary: fruit juice (any type), food coloring, sodium alginate, calcium chloride, water, lemons, red cabbage, baking soda, and vegetable oil.

The Experiencing Phase

Fruit Caviar

The goal of the experiment is to create colored spherical droplets (fruit caviar) with a solution of sodium alginate and calcium chloride. The experiment starts by building the fluidic circuit as shown in the schematic in Figure 2. There are two inlets, both of which are connected to nonfunctional blocks. These parts terminate in a functional droplet generator block. The outlet of the droplet generator is linked to a mixing block, which ends in a reservoir. For this experiment we use two simple syringe pumps (see Figure 1): pump 1 is filled with air, while pump 2 is filled with a solution of sodium alginate (1.8% w/w) in water and fruit juice. Once the pumps are turned on, the fluids from the pumps meet at the droplet generator block: here the two streams are conveyed in one stream where droplets of the sodium alginate solution are created. The size and frequency of the droplets can be adjusted varying the flow rate of the pumps. The reservoir was previously filled with a solution of calcium chloride (0.25 M). The inlet at the reservoir is functionalized with an appendix that guides the flow created by the bubble generator inside the reservoir. The solution of sodium alginate, once in contact with the calcium chloride solution, starts to gel. The goal of the experiment is to tune the pumps to an appropriate flow rate that allows the creation of a steady flow of sodium alginate droplets with a diameter of approximately 3 mm. The stream is gently guided in the static solution of calcium chloride, where it forms beautiful spherical particles, the so-called “fruit caviar”.

Veggi Alchemy

In this experiment, the goal is to visualize a chemical reaction obtained with natural ingredients that can be found in a normal kitchen. As seen in the schematic of Figure 3, in this experiment the students will assemble a fluidic circuit with three inlets and one outlet.

Figure 3.

“Veggi alchemy” experiment. From left to right: layout of the experiment with the modular blocks assembled and placed on the supporting mat; schematic of the assembly that the children have to build in order to perform the experiment; final results of the experiment, with the chromatic change achieved inside the circuit built, obtained with the modulation of the pH of the flowing solution.

Two pumps are used: water saturated with baking soda is distributed by pump 1, while freshly squeezed lemon juice is dispensed by pump 2. A third solution, the “indicator solution”, is obtained by chopping a fresh red cabbage and mixing the cut leaves in warm water. Once the water cools and shows a strong purple color, the cabbage is filtered out and the solution is collected in a syringe (syringe number 3 in the schematic of Figure 3) that is actuated manually. The functionalized parts used are three mixing chambers, sequentially connected in the middle of the circuit, each alternating with a coiled channel. The mixing blocks feature a spherical hollow chamber that allows clear observation of the liquid that flows through the circuit. Furthermore, each mixing chamber has three inlets and one outlet. Once the circuit is built, the pumps are turned on and tuned to the specified flow rate. Simultaneously, the third pump is manually actuated to push the indicator solution in the circuit. The user will be able to observe the fluids fill the blocks: after a short transitory phase, each of the chambers on the three functionalized blocks will have a different color. The first chamber will have the purple color of the cabbage solution, the second chamber will turn dark blue, and the third chamber will show a bright pink color. This experiment exploits the presence in red cabbage of anthocyanin, a pigment that is sensible to pH and changes its color accordingly. In the first chamber, the solution has a pH close to 7, thus maintaining the purple color. However, in the second chamber, pump 1 is pumping a basic solution of baking soda, increasing the pH and turning the solution dark blue. In the third step, the acidic lemon juice decreases the pH, resulting in another chromatic change: the solution turns bright pink (Figure 3).

Space Juice

In this simple experiment, a reservoir with two chambers is used. Two identical submarine-like parts that can be filled with fluid have been designed and 3D-printed and are used in combination with the modular kit (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

“Space juice” experiment. From left to right: layout of the experiment with the modular blocks assembled and placed on the supporting mat together with the “space submarine”; schematic of the assembly that the children have to build in order to perform the experiment; final results of the experiment, where it is possible to see two phenomena, the different behavior of the two submarines and the spatial separation between oil and water due to their different specific weights.

These parts are filled with 2.5 mL of sunflower oil and positioned in each of the empty compartments of the reservoir. Afterward, the two syringe pumps are filled with sunflower oil and colored water, respectively, and connected via two tubes to the reservoir. Once the pumps are turned on, the two chambers start to fill: in the section with water, the submarine will float, while in the oil section it will stay on the bottom of the reservoir. This happens because the volume of oil injected in the submarines is calculated in order to achieve a density higher than that of sunflower oil but lower than that of water. Once the reservoir has been filled almost to the top, the pumps are paused, the connections to the reservoir are switched (the oil syringe goes to the water section and vice versa), and the pumps are turned on again. The fluids entering from the bottom of the reservoir will act differently: the oil will create bubbles and will rise to the top; the water will stay on the bottom, creating a large colored bubble on the bottom of the reservoir. Again, this phenomenon is due to the different densities of the fluids.

The Learning Phase

During the experiments, multiple physical and chemical processes are happening. After experiencing “hands-on” the scientific phenomena, the pupils can be introduced to these concepts. The first phase of experiencing ends and the second phase of learning starts. Thanks to the handbook provided (Appendix 1), the students will be guided in this second phase with intuitive explanations of the basic principles underlying the experiments. They will also be challenged to test their understanding of the phenomena observed by a short questionnaire provided at the end of each experiment. In this way, the teacher can have a first insight into the efficacy of the method. The complexity of the concepts explained in the handbook and of the questionnaire provided can be easily tuned on the basis of the age and background knowledge of the students.

Fruit Caviar

For the “fruit caviar” experiment, the handbook (Appendix 1) provided introduces some basic concepts that help to put the experiment into context. Furthermore, the teacher can introduce specific concepts on the basis of the skill level of the students. The concept of polymeric chains can be introduced together with the concept of polysaccharides such as sodium alginate. At this point, the students will be confronted with the fact that both compounds (sodium alginate and calcium chloride) are in liquid form when they are in a water solution, but specific bonds are created when the solutions are mixed together. An introduction to different types of bonds will be made, followed by an explanation of the creation of the specific bond between the alginate and the calcium ions seen in the experiment. For the most advanced users, the learning process will be taken one step further, not only introducing the chemistry concepts mentioned but also focusing on the physical process behind the creation of the droplets. The droplet generator works by exploiting the shear forces between two immiscible phases. The students will be introduced to the concept of viscosity, surface tension, shear force, and laminar and turbulent flow and how these factors affect the formation of the droplets in the fruit caviar experiment. Finally, the questionnaire in the handbook will assess to what extent these concepts have been assimilated.

Veggi Alchemy

This experiment is intended to introduce the students to the concept of pH. With reference to their everyday experience, the handbook (Appendix 1) explains what acids and bases are. The pH scale is introduced and the concept of a pH indicator explored. Students can then be introduced to pH-sensitive molecules, especially to anthocyanin, the pigment present in red cabbage responsible for the pH sensitivity of the solution. The structure of the molecule will be shown, focusing on the presence of the functional groups that get protonated or deprotonated, causing a shift in the absorbance spectrum. In the handbook, the questionnaire has the goal of assessing if the students understood the idea of pH and how it is measured. For the higher-level students, the experiment can be further used to challenge their analytical skills. By knowing the flow rates selected for lemon juice and baking soda solution syringes and measuring the flow rate of the manually actuated syringe (reading the volume on the syringe and measuring the injection time with a stopwatch), the students will be challenged to calculate (approximately) the volume ratios of the three solutions in each mixing chamber where the color is observed. By starting from the volumes and by knowing the pH of each solution, they will calculate the pH of the mixed liquid in each chamber, comparing the obtained value with the pH color scale of anthocyanin.

Space Juice

The space juice experiment aims to introduce the concepts of density and buoyancy. Despite the two printed submarines being completely identical and filled with the same amounts of the same fluid, they behave differently due to the different fluid that surrounds them. Through the handbook (Appendix 1), the students are introduced to the concepts of density, weight, and buoyancy. In the experiment they will see how density is a property of an object as well as of a substance and that it has a direct influence on its dynamic behavior. Finally, buoyancy can be introduced, completing the explanation of the balance of forces acting on a body immersed in a fluid: the floating submarine is floating because of the equilibrium of forces created between gravity and buoyancy, while the submerged submarine met an equilibrium of forces at the bottom of the reservoir. The questionnaire provided (Appendix 1) includes a series of questions that stimulate the critical thinking of the children, challenging them to explain the phenomena observed on the basis of the information acquired from the handbook.

Conclusion

While the work presented in this paper only describes three experiments, many more applications can be developed and performed due to the modular nature of the kit and the ease of production of its building blocks. In the same way, it is possible to expand on the explanatory part, introducing new concepts and phenomena that are involved in the experiments, as well as the handbook. Even the pumps offer the possibility for the students to explore principles of coding: the Arduino board that controls the pumps through the dedicated module, can be accessed through a USB cable and easily reprogrammed to perform specific tasks. The effects of introducing new teaching methods that are more engaging and fun for primary school students have been shown to not only improve the desired learning results20 but also increase the collaboration and engagement21,22 of classes where such methods have been implemented. This kit presented in this work is an extremely flexible platform that, rather than focusing on one specific type of skill, leaves room to the imagination of its user. Children can learn while playing, allowing them to get passionate and more confident about their capabilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Stichting Universiteitsfonds Limburg (SWOL) and Limburg Meet (LIME) for funding of the project.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c01115.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bybee R. W. Achieving Technological Literacy: A National Perspective. Technol. Teach. 2000, 60 (1), 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dugger W. E.Evolution of STEM in the United States. 6Th Bienn. Int. Conf. Technol. Educ. Res. March 1–8, 2010.

- Hogan J.; Down B.. A STEAM School Using the Big Picture Education (BPE) Design for Learning and School - What an Innovative STEM Education Might Look Like. Internetional J. Innov. Sci. Math. Educ. 2015, 23 ( (3), ). [Google Scholar]

- Bissaker K. Transforming STEM Education in an Innovative Australian School: The Role of Teachers’ and Academics’ Professional Partnerships. Theory Pract. 2014, 53 (1), 55–63. 10.1080/00405841.2014.862124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce A.Stimulating Interest in STEM Careers among Students in Europe: Supporting Career Choice and Giving a More Realistic View of STEM at Work. Educ. Employers Taskforce Res. Conf. 2014.

- ICF ; Cedefop. EU Skills Panorama (2014) STEM Skills Analytical Highlight, 1–5; 2015.

- Tuluri F.Using Robotics Educational Module as an Interactive STEM Learning Platform. In ISEC 2015 - 5th IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference, 2015, p 16. 10.1109/ISECon.2015.7119916 [DOI]

- Rizzardini R. H.; Gütl C.. A Cloud-Based Learning Platform: STEM Learning Experiences with New Tools. In Handbook of Research on Cloud-Based STEM Education for Improved Learning Outcomes; 2016; 106. 10.4018/978-1-4666-9924-3.ch008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinger C. W.; Castiaux A.; Speed S.; Spence D. M. Plate Reader Compatible 3D-Printed Device for Teaching Equilibrium Dialysis Binding Assays. J. Chem. Educ. 2018, 95, 1662. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wietsma J. J.; Van Der Veen J. T.; Buesink W.; Van Den Berg A.; Odijk M. Lab-on-a-Chip: Frontier Science in the Classroom. J. Chem. Educ. 2018, 95 (2), 267–275. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava K. C.; Thompson B.; Malmstadt N. Discrete Elements for 3D Microfluidics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111 (42), 15013–15018. 10.1073/pnas.1414764111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltri L. M.; Holland L. A. Microfluidics for Personalized Reactions to Demonstrate Stoichiometry. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 1035. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vangunten M. T.; Walker U. J.; Do H. G.; Knust K. N. 3D-Printed Microfluidics for Hands-On Undergraduate Laboratory Experiments. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 178. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabassum T.; Iloska M.; Scuereb D.; Taira N.; Jin C.; Zaitsev V.; Afshar F.; Kim T. Development and Application of 3D Printed Mesoreactors in Chemical Engineering Education. J. Chem. Educ. 2018, 95 (5), 783–790. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinger C. W.; Geiger M. K.; Spence D. M. Applications of 3D-Printing for Improving Chemistry Education. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 112. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scalfani V. F.; Vaid T. P. 3D Printed Molecules and Extended Solid Models for Teaching Symmetry and Point Groups. J. Chem. Educ. 2014, 91, 1174. 10.1021/ed400887t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S. C. 3D Printing of Protein Models in an Undergraduate Laboratory: Leucine Zippers. J. Chem. Educ. 2015, 92, 2120. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt B.; King D.; Kariuki J. Designing and Using 3D-Printed Components That Allow Students to Fabricate Low-Cost, Adaptable, Disposable, and Reliable Ag/AgCl Reference Electrodes. J. Chem. Educ. 2018, 95, 2076. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booeshaghi A. S.; Beltrame E. da V.; Bannon D.; Gehring J.; Pachter L. Principles of Open Source Bioinstrumentation Applied to the Poseidon Syringe Pump System. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12385. 10.1038/s41598-019-48815-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidt B.; Rogosic R.; Bonni S.; Passariello Jansen J.; Dimech D.; Lowdon J. W.; Arreguin-Campos R.; Steen Redeker E.; Eersels K.; Diliën H.; van Grinsven B.; Cleij T. J. The Liberalization of Microfluidics: Form2 Benchtop 3D Printing as an Affordable Alternative to Established Manufacturing Methods. Phys. Status Solidi A 2020, 217, 1900935. 10.1002/pssa.201900935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gali T.; Lavin E. S.; Donovan K.; Raja A. Science Alive!: Connecting with Elementary Students through Science Exploration †. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2016, 17, 275. 10.1128/jmbe.v17i2.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T. Developing Numeracy Skills Using Interactive Technology in a Play-Based Learning Environment. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2018, 5, 39. 10.1186/s40594-018-0135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.