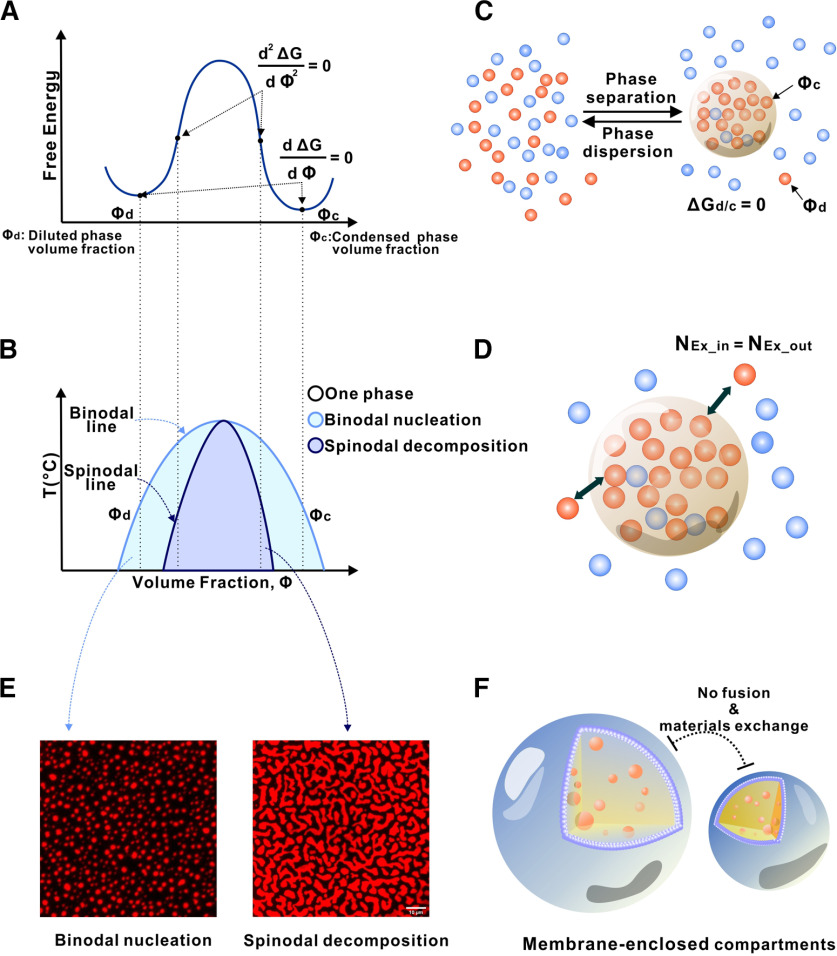

Figure 1.

Phase separation illustrated by a simple two-component system. A, Free energy diagram showing phase separation of a two-component system (e.g., a protein indicated by blue dots; in water indicated by brown dots) under a certain condition. A uniformly mixed system can undergo phase separation by lowering the free energy to its minima, which results in a two-phase system: a dilute phase (Φd, expressed as fraction volume for the dilute phase) and a condensed phase (Φc, fraction volume for the condensed phase). B, Phase diagram of the two-component system constructed by plotting the free energy minima as a function of temperature. Blue curve indicates a sharp boundary (or the threshold concentration) of the system transitioning from a homogeneous single-phase state to a two-phase state. Within the phase separation region, two modes of phase separation, binodal nucleation and spinodal decomposition, can occur. C, In a phase-separated two-component system, a thermodynamic equilibrium is reached (i.e., ΔGd/c = 0). A sharp gradient in the concentration of the blue molecule is established between the two phases. D, After phase separation, the components of the condensed phase and the diluted phase can freely exchange. However, there is no net flow of components between the two phases. E, An example of binodal nucleation-induced phase separation forming condensed spherical droplets (left) and an example of spinodal decomposition-induced phase separation forming worm-like condensed networks (right). F, In sharp contrast to membraneless condensates, spontaneous compartment fusion or materials exchange does not occur in membrane-separated organelles.