Abstract

Background & objectives:

Breast cancer remains the most common malignancy among women worldwide. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been shown to play critical roles in tumour initiation and progression. This study was aimed to evaluate the potential role of lncRNA highly upregulated in liver cancer (HULC) in breast cancer.

Methods:

The expression of HULC was evaluated in breast cancer patients and cell lines using real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Small interfering RNA-based knockdown was also employed to study the potential role of HULC in breast cancer cell lines including ZR-75-1, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231.

Results:

HULC was significantly upregulated in tumour tissues compared to non-tumoural margins (P<0.001). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis demonstrated the biomarker potential of HULC (ROCAUC=0.78, P<0.001). The HULC knockdown induced apoptosis and suppressed cellular migration in breast cancer cell lines.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Our results indicated that HULC was upregulated in breast cancer and might play a role in tumourigenesis. The HULC may have a potential to be exploited as a new biomarker and therapeutic target in breast cancer.

Keywords: Biomarker, breast cancer, HULC, long non-coding RNA, small interfering RNA

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy and the second leading cause of death in women worldwide1. This is classified according to molecular subtype into the four main groups in which triple-negative subtypes are more often highly invasive, spreading to lymph nodes while primary tumours are small and leading to early relapse with increased risk of visceral metastasis and poor outcome2. Applying genetic biomarkers could be one of the diagnostic and/or prognostic criteria in this area. Therefore, understanding the molecular and genetic networks that control the initiation, progression and spread of cancer will be useful for finding potential biomarkers. The transcriptome sequencing technologies have revealed that around 90 per cent of the human genome is actively transcribed into non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), while nearly 20,000 genes, accounting for less than two per cent of the genome, encode proteins3.

Long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) are endogenous cellular RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides in length4. Emerging evidence indicates that lncRNAs play an important role in various cell pathways, including proliferation and apoptosis5,6, autophagy7, epigenetics8, invasion and metastasis9 and lipid metabolism10. Aberrant expression of lncRNAs may cause adverse effects on biological processes and lead to many diseases particularly different kinds of cancers including glioma11, osteosarcoma12, lung cancer13 and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)14.

Highly upregulated in liver cancer (HULC) gene was reported for the first time as the most overexpressed lncRNA in patients with HCC15, and also its potential as a diagnostic biomarker has been proposed16,17. LncRNA HULC with two exons, but no protein-coding function is located on chromosome 6p24.3. Cumulating evidence has shown that HULC is not HCC-specific lncRNA, but it is also involved in other cancers such as gastric7 and glioma11. However, there are no data on the potential role of HULC in breast cancer.

Therefore, this study was aimed to detect and evaluate the expression level of HULC in breast invasive ductal carcinoma and its role as a potential biomarker.

Material & Methods

Human tissue specimens: Fifty two specimens of surgically resected breast tumours with invasive ductal carcinoma subtype and their adjacent non-tumour tissues were collected from Emam Reza and Noor-Nejat hospitals, Tabriz, Iran, from women of age range, 34-80 (51.29±1.73) years. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to sample collection and also, this study was carried out with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (approval number: IR.TBZMED.REC.1392.249), during September 2014 till March 2018. The specimens were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen after surgery and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. To classify the tumours, the tumour, node and metastasis (TNM) staging was done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer18.

Cell culture: All human breast cancer cell lines including ZR-75-1 (ATCC No. CRL-1500), MCF-7 (ATCC No. HTB-22), MDA-MB-231 (ATCC No. HTB-26) and SkBr-3 (ATCC No. HTB-30) were obtained from the cell bank of Pasteur Institute (Tehran, Iran). ZR-75-1, MCF-7 and SkBr-3 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640) (Gibco, Life Technologies, USA), while MDA-MB-231 was grown in DMEM (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 10 per cent heat-inactivated FBS (foetal bovine serum) (Gibco, USA) and 100 U/ml of penicillin/streptomycin (10,000 U/ml, Gibco, USA) at 37°C in a humidified environment containing five per cent CO2.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR): Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA (complementary DNA) was synthesized by reverse transcription of 1 μg of total RNA using the PrimeScript RT kit (Takara, China) by following the manufacturer's protocol. The real-time qRT-PCR was carried out with primers specific for HULC, Bax, Bcl-2, CDH1, VIM, MMP-9 and β-actin using SYBR® Premix EX TaqTM II (Tli RNaseH Plus, Takara, PR China) by Corbett Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Life Sciences, Germany). Primer sequences and real-time qRT-PCR conditions have been outlined in Table I. β-actin served as an endogenous control for normalization. The identity of HULC gene after being amplified in PCR was further confirmed by sequencing.

Table I.

Sequences of primers used and their real-time qRT-PCR programmes

| Genes | Primer sequence (5’- 3’) | Real-time qRT-PCR programme# | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HULC | F: ATCGTGGACATTTCAACCTC | D: 95°C for 25 sec | 161 |

| R: GCTGTGCTTAGTTTATTGCC | A: 59°C for 25 sec | ||

| E: 72°C for 25 sec | |||

| Bax | F: GCAAACTGGTGCTCAAGG | D: 95°C for 30 sec | 236 |

| R: ACTCCCGCCACAAAGA | A: 63°C for 35 sec | ||

| E: 72°C for 30 sec | |||

| Bcl-2 | F: TGGGAAGTTTCAAATCAGC | D: 95°C for 25 sec | 298 |

| R: GCATTCTTGGACGAGGG | A: 63°C for 30 sec | ||

| E: 72°C for 30 sec | |||

| CDH1 | F: AGTACAACGACCCAACCCAAG | D: 95°C for 30 sec | 235 |

| R: GCAAGAATTCCTCCAAGAATCC | A: 57°C for 22 sec | ||

| E: 72°C for 20 sec | |||

| VIM | F: CAGGCAAAGCAGGAGTCCA | D: 95°C for 30 sec | 122 |

| R: AAGTTCTCTTCCATTTCACGCA | A: 59°C for 35 sec | ||

| E: 72°C for 30 sec | |||

| MMP-9 | F: CCGCTCACCTTCACTCGC | D: 95°C for 30 sec | 174 |

| R: ACCACAACTCGTCATCGTC | A: 63°C for 35 sec | ||

| E: 72°C for 30 sec | |||

| β-actin | F: AGAGCTACGAGCTGCCTGAC | D: 95°C for 30 sec | 184 |

| R: GCAAGAATTCCTCCAAGAATCC | A: 59°C for 30 sec | ||

| E: 72°C for 30 sec |

#real-time qRT-PCR cycling was started for all primers with initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes. D, denaturation; A, primer annealing, E, extension; real-time qRT-PCR, real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; F, forward; R, reverse

Small interferingRNA (siRNA) transfection: To investigate the role of HULC, its expression was suppressed through siRNA-mediated gene knockdown. Therefore, pre-designed negative control scrambled siRNA (si-NC) was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, USA) and pre-designed si-HULC, against HULC, (target sequence: 5'-GGCCGGAATATTCTTTGTTTA-3') was purchased by Qiagen, Germany. Both siRNAs were labelled with 6-FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) at their 3' end and transfected into cells using HiPerFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Assays were conducted 72 h after transfection.

Study of apoptosis: To determine apoptosis, acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EtBr) staining was done. Breast cancer cell lines, including MCF-7 (1.5×105), MDA-MB-231 (1×105) and ZR-75-1 (2.5×105), were seeded into 24-well plates (MatTek, USA) and cultured for 24 h, followed by transfection with si-HULC and si-NC separately according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Germany and Dharmacon, USA, respectively). After 72 h, the cells were collected by traditional trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (0.25%; HyClone, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) treatment and transferred onto glass microscope slides followed by staining with AO/EtBr. Finally, the cells were analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX 41, Germany). Expression levels of genes involved in apoptosis such as Bax and Bcl-2 were also evaluated by real-time qRT-PCR alongside morphological evaluation of the apoptotic cells.

Cell cycle analysis: For cell cycle analysis, MCF-7 (1.5×105), MDA-MB-231 (1×105) and ZR-75-1 (2.5×105) cell lines were seeded into 24-well plates for 24 h. The cells were transfected with si-HULC and si-NC separately according to the manufacturer's instruction (Qiagen, Germany and Dharmacon, USA, respectively). After 72 h, the cells were detached by trypsin-EDTA solution at 37°C for five minutes (MCF-7 and ZR-75-1) and two minutes (MDA-MB-231), followed by inhibiting trypsin activity by adding 10 per cent FBS. Afterwards, the cells were collected by traditional trypsin-EDTA treatment and washed by cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, followed by fixation using ice-cold ethanol (70% w/w). The cells were incubated in a freshly prepared solution containing 0.1 per cent Triton X-100, RNase A (50 μg/ml; Fermentas, USA), and propidium iodide (PI) (50 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 4 °C for 15 minutes. The stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer, BD Biosciences, USA). The percentages of measured cells in the sub-G1 and G1 phases were analyzed by FlowJO 7.6.1 software (BD, USA). The experiments were conducted three times independently.

Wound healing assay: In order to get around 90 per cent confluency after 24 h of culturing, each cell line was seeded at appropriate numbers into 24-well plates in complete medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, USA). After 24 h, a single wound was created in the middle of the well using a sterile 200 μl pipette tip. After removing detached cells with PBS, each cell line was separately transfected by si-HULC and si-NC according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen, Germany and Dharmacon, USA, respectively). After 72 h, the cells migrated into the wound area were photographed under the inverted microscope (Olympus, Japan). Beside wound healing assay, the expression of some genes involved in invasion and metastasis including CDH1 (E-cadherin), VIM (vimentin) and MMP-9 (matrix metallopeptidase-9) was also evaluated at mRNA levels. Since vimentin is usually undetectable in MCF-7 and ZR-75-1, and E-cadherin is below the detection limit in MDA-MB-231, CDH1 and MMP-9 expression were evaluated at mRNA levels in ZR-75-1 and MCF-7 and VIM and MMP-9 in MDA-MB-231.

Statistical analysis: Relative Expression Software Tool (REST) 2009 (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia), was used to evaluate the expression of HULC in breast cancer tissues compared to non-tumoural counterparts. The fold change and relative expression levels of studied genes in treated versus non-treated cells were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt and 2−ΔCt methods19, respectively. In these methods, ΔCt=Ct (HULC) – Ct (β-actin) and ΔΔCt=ΔCt(treated cells) – ΔCt(control), where Ct is cycle threshold. Statistical analysis between two groups was performed by Student's t test and for more than two groups; one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was applied. Data were analyzed by SPSS software v22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). To assess the biomarker potential of HULC in breast cancer a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn using SigmaPlot software v12.5 (Systat Software Inc., USA). All experiments were repeated three times, and data were represented as mean±standard error of mean.

Results

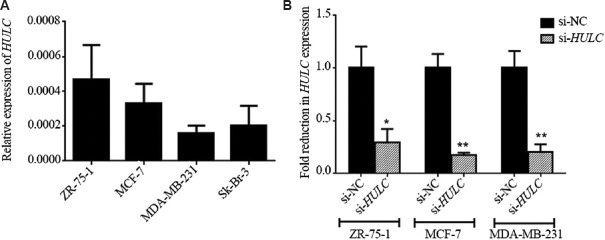

HULC overexpressed in breast cancer tissues: Our preliminary data showed that HULC was expressed in breast tumour tissues (Fig. 1A and B) and fold change expressions of HULC at mRNA levels calculated through REST, were significantly upregulated by 8.26-fold in cancerous tissues compared to non-cancerous specimens (8.258±0.726, P<0.001) (Fig. 1B). The high expression of HULC was significantly associated with advanced clinical stages of studied samples (P=0.025). Moreover, a marginal association was observed between elevated expression of HULC and lymph node metastasis (P=0.052) and high oestrogen receptor expression (P=0.088) (Table II). No association between expression of HULC and other clinicopathological characteristics, including age, differentiation, progesterone and HER-2 expression levels and tumour location, were found (Table II). ROC curve analysis was employed to determine whether or not tumour and non-tumour tissue could be distinguished by the expression level of HULC. Pair-matched adjacent normal tissues were used as a control to plot ROC curve. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.78 (P<0.001) indicating its potential as a biomarker (Fig. 1C). The sensitivity and specificity were 0.71 and 0.77, respectively, and the cut-off value was 17.1.

Fig. 1.

Expression of HULC in breast cancer and receive operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for predicting breast cancer prognosis. (A) Confirmation of HULC expression by Sanger sequencing. (B) Real-time qRT-PCR analysis of HULC expression level in cancerous and adjacent non-tumour breast tissues. Values are mean±SEM (n=3). (C) ROC curve for HULC to discriminate between tumour and non-tumour tissues. The area under the ROC (AUC) is 0.78 (P<0.001). The sensitivity and specificity were 0.71 and 0.77, respectively and cut-off value was 17.1. Real-time qRT-PCR, real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Table II.

Relationship between highly upregulated in liver cancer expression (HULC) levels and clinicopathological features of patients with breast cancer (n=52)

| Characteristics | Number of patients (%) | HULC mean (ΔCt)±SEM | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | |||

| <45 | 24 (46.7) | 15.46±0.75 | 0.537 |

| >45 | 28 (53.3) | 14.86±0.63 | |

| Tumour size (cm) | |||

| <2 | 24 (46.2) | 14.22±0.69 | 0.182 |

| >2 | 20 (38.5) | 15.68±0.84 | |

| TNM clinical stage | |||

| I | 17 (32.7) | 17.10±0.66 | 0.025 |

| II | 14 (26.9) | 14.45±1.01 | |

| III | 14 (26.9) | 13.74±0.87 | |

| Lymphatic metastasis | |||

| Absent | 17 (32.7) | 15.80±0.61 | 0.052 |

| Present | 28 (53.8) | 13.66±0.94 | |

| Differentiation | |||

| Poor | 5 (9.6) | 12.56±1.46 | 0.284 |

| Moderate | 35 (67.3) | 15.26±0.58 | |

| Well | 5 (9.6) | 15.53±2.13 | |

| Progesterone expression (%) | |||

| <30 | 13 (38.2) | 14.91±1.21 | 0.914 |

| >30 | 21 (61.8) | 15.06±0.77 | |

| Oestrogen expression (%) | |||

| <30 | 17 (32.7) | 16.12±0.79 | 0.088 |

| >30 | 17 (32.7) | 13.89±0.99 | |

| HER-2 status | |||

| Negative | 16 (30.8) | 14.93±1.04 | 0.891 |

| Positive | 15 (28.8) | 15.13±0.98 | |

| Location | |||

| Right | 20 (38.5) | 14.81±0.84 | 0.549 |

| Left | 23 (44.2) | 15.45±0.68 |

HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2; TNM, tumour, node, and metastasis; SEM, standard error of mean

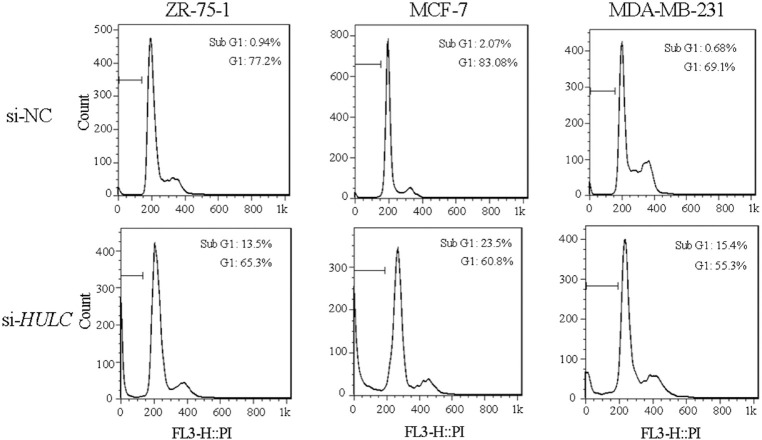

Expression of HULC in breast cancer cell lines: To further explore the potential role of HULC in breast cancer, siRNA-based knockdown was employed in ZR-75-1, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Data for expression of HULC in breast cancer cell lines have been illustrated in Figure 2A. Real-time qRT-PCR analysis of HULC expression levels was performed 72 h after transfection indicating knockdown efficiency >70 per cent for all cell lines (Fold reduction in HULC expression was significant (P< 0.05 & <0.01) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

HULC expression in breast cancer cell lines and small interfering (si) RNA -mediated knockdown. (A) HULC expression levels in breast cancer cell lines including ZR-75-1, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and Sk-Br-3. (B) The efficiency of si RNA-mediated knockdown was evaluated 72 h after transfection by real-time qRT-PCR in the cell lines. P*<0.05, **<0.01 compared to si-NC. si-NC, small interfering RNA negative control.

HULC silencing induces apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines: To study apoptosis, treated and non-treated cells were stained with AO/EtBr, and analyzed under fluorescence microscope. The result showed that the knockdown of HULC induced apoptosis-related morphological changes, such as nucleus condensation, cell membrane blebbing and cytoplasmic vacuolization compared to control cells (Fig. 3A-C).

Fig. 3.

Effects of HULC knockdown on apoptosis. (A-C) Morphological evaluation of the apoptotic cells stained with acridine orange/ethidium bromide. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. Magnification, ×200. (D-F) Expression of Bax and Bcl-2 in ZR-75-1, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 by real-time qRT-PCR after HULC knockdown. Values are mean±SEM (n=3). P*<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001 compared to si-NC.

Consistent with the results from morphological evaluation, the gene expression data revealed that HULC silencing significantly upregulated Bax expression at mRNA level in ZR-75-1 (P=0.001) and but had no significant effect on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231. In addition, HULC knockdown significantly downregulated Bcl-2 expression at mRNA level in ZR-75-1 (P<0.05), MCF-7 (P=0.001) and MDA-MB-231 (P=0.001) (Fig. 3D-F).

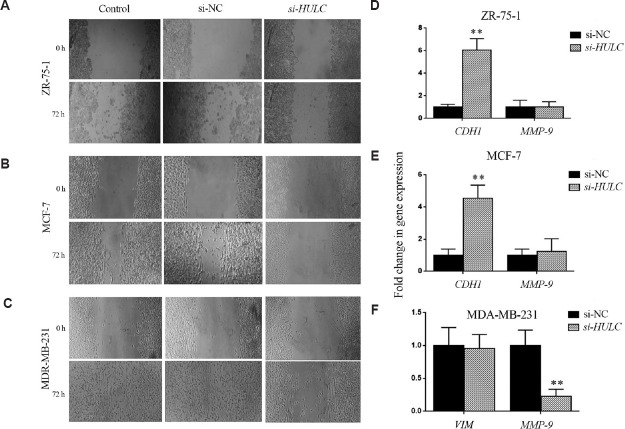

HULC knockdown can affect cell cycle: To study the growth inhibitory effect of HULC knockdown, cell cycle analysis was done using flow cytometry. The percentages of cell population in sub-G1and G1phase in si-NC-transfected ZR-75-1 (as a control) were 0.94 and 77.2 per cent, respectively, and after 72 h transfection with si-HULC in the mentioned phases were 13.5 and 65.3 per cent, respectively. Cell population percentage in sub-G1 and G1 in si-NC-transfected MCF-7 (as a control) were 2.07 and 83.8 per cent, respectively, and after 72 h transfection with si-HULC were 23.5 and 60.8 per cent, respectively. Measured cell population percentage in si-NC-transfected MDA-MB-231 (as a control) in sub-G1 and G1 were 0.68 and 69.1 per cent, respectively, and after 72 h transfection with si-HULC in the mentioned phases were reported to be 15.4 and 55.3 per cent, respectively. Thus, there was a significant reduction in G1 phase in the studied cell lines (P<0.05), while the cell percentage in the sub-G1, representing apoptotic cells, was significantly increased following 72 h of HULC depletion (P<0.05) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cell cycle analysis. ZR-75-1, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-23 cells were transfected with si-NC and si-HULC. Propidium iodide (PI) staining was done 72 h after transfection. The range gate illustrated on FACS plots indicates sub-G1.

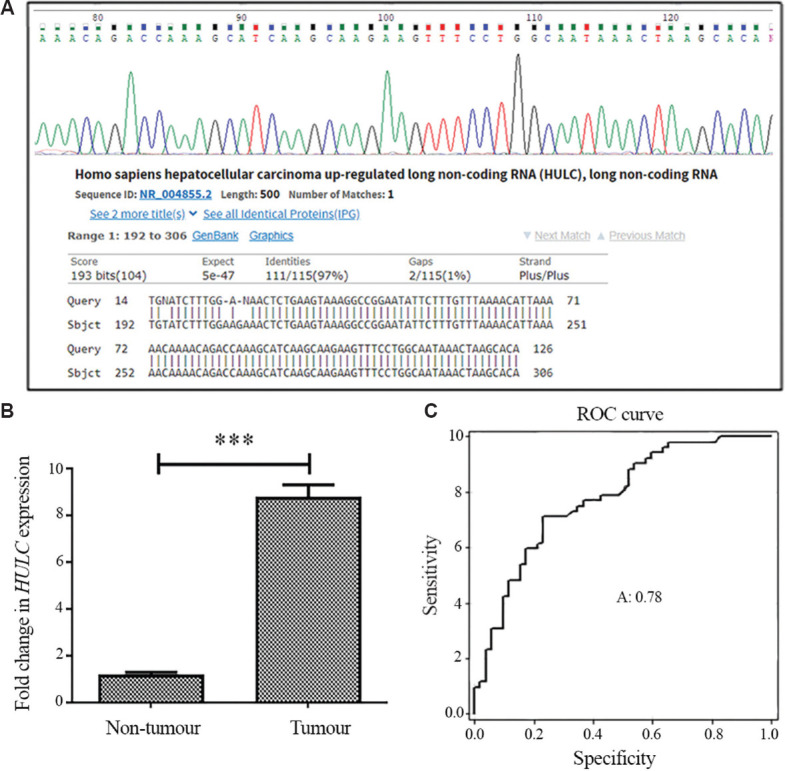

HULC silencing affects epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT): To investigate the role of HULC in cell migration and EMT, the invasive behaviour of MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and ZR-75-1cells was studied following HULC attenuation using wound-healing assay. The expression of invasive genes was studied by real-time qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 5A-C, knockdown of HULC significantly decreased cell migration capacity compared to non-transfected parental cells or si-NC-treated cells (P<0.05). Consistent with the wound healing assay results, depletion of HULC significantly upregulated E-cadherin in ZR-75-1 cells (P<0.01) and MCF-7 cells (P=0.01), while vimentin had no significant change in MDA-MB-231. The knockdown of HULC downregulated MMP-9 expression in MDA-MB-231 (P<0.01) and had no significant effect on ZR-75-1 and MCF-7 (Fig. 5D-F).

Fig. 5.

Effects of HULC knockdown on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. (A-C) Scratch wound healing assay was performed in control and small interfering RNA -treated breast cancer cell lines ZR-75-1, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231. Magnification, ×100. (D-F) Analysis of CDH1, VIM and MMP-9 expression in breast cancer cell lines by real-time qRT-PCR after HULC knockdown. Values are mean±SEM (n=3). **P<0.01 comapred to si-NC.

Discussion

In view of the crucial roles of a new class of ncRNAs named lncRNAs in cancer development20,21, and high incidence of breast cancer among women worldwide1, the present study was performed to examine the expression levels of lncRNA HULC as well as its cellular role in breast cancer. In concordance with earlier studies7,15,22, our results demonstrated upregulation of HULC in breast tumour tissues compared to adjacent non-tumour tissues. Our results revealed the elevated expression levels of HULC in advanced clinical stages compared to tumours with early stages. In accordance with the previous studies carried out by Panzitt et al15 and Yang et al17 in HCC and gastric cancer, respectively, our results also showed the biomarker potential of HULC in breast cancer.

Inducing apoptosis is an important tool in controlling tumour development. Emerging evidence has demonstrated that increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio as a hallmark of apoptosis, upregulates caspase-3 and increases apoptosis23,24,25. In 2017, Wang and colleagues22 reported that HULC conspicuously inhibited apoptosis through increase in Bcl-2 expression levels. Another study performed by Chen et al26 revealed that HULC silencing affected apoptosis through upregulation of Bax gene. Our findings showed a relationship between HULC depletion and apoptosis mostly through reduction in Bcl-2 and an increase in the ratio of Bax to Bcl-2 expression in breast cancer cell lines. Moreover, apoptosis was further confirmed through increased sub-G1 area in cell cycle analysis.

Cancer metastasis as a major cause of cancer mortality begins with acquiring EMT and invasive properties causing the spread of metastatic cells from primary tumour to different sites27. The loss of E-cadherin (epithelial marker) as one of the critical steps in EMT and invasion28,29 has been considered by many researchers. Li et al30 speculated that lncRNA HULC could influence cell migration and invasion through HULC-EMT pathway. Zhao et al7 discovered for the first time that HULC was a positive regulator of EMT. They showed that HULC depletion induced a repertoire of biochemical and morphological changes causing EMT suppression. In consistent with these findings, our results showed that HULC depletion could decrease migration of breast cancer cells and also supress EMT through an increase in the expression of CDH1. Upregulation of MMP-9, one of the most widely investigated MMPs, has been reported to play a significant role in different cancers31. In this study, a significant reduction of MMP-9 expression was shown in only MDA-MB-231 cells following HULC knockdown. Since MMP-9 is highly expressed in triple-negative tumours and is associated with a tumorigenic expression profile and plays critical roles in the metastatic behaviour of MDA-MB-231 cells32; we suppose that HULC silencing can probably downregulate MMP-9 only in this cell lines.

In this study, HULC silencing resulted in a significantly lower expression of Bcl-2 and higher expression of CDH1 in breast cancer cells. Our results were consistent with a proposed mechanism in which the upregulation of Bcl-2 led to loss of CDH1 and decreased CDH1-mediated cell-cell adhesion as well as invasion33,34. Thus, based on our results, one possibility for upregulation of Bcl-2 and loss of CDH1 might be due to the role of HULC in apoptosis via modulating Bcl-2 expression, which in turn results in the regulation of CDH1 levels33,34. However, the concrete mechanisms of how HULC regulates genes implicated in metastasis and apoptosis remain to be explored in the future.

To summarize, our findings suggest that HULC can be a potential molecular marker for breast cancer and may provide further evidence of its vital role in the biology of cancer. This study also provides preliminary data on the importance of this lncRNA as a possible target therapy against breast cancer.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: Authors acknowledge the Iranian National Science Foundation (grant no. 93045001), Iran, for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Fedewa SA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2017: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:100–21. doi: 10.3322/caac.21392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagtap SV. Evaluation of CD4+ T-cells and CD8+ T-cells in triple-negative invasive breast cancer. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2018;61:477–8. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_201_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteller M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:861–74. doi: 10.1038/nrg3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng W, Wang Z, Fan H. LncRNA NEAT1 impacts cell proliferation and apoptosis of colorectal cancer via regulation of Akt signaling. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23:651–6. doi: 10.1007/s12253-016-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Sun Z, Zhu J, Xiao B, Dong J, Li X. LncRNA-TCONS_00034812 in cell proliferation and apoptosis of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and its mechanism. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:4801–14. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, Guo Q, Chen J, Hu J, Wang S, Sun Y. Role of long non-coding RNA HULC in cell proliferation, apoptosis and tumor metastasis of gastric cancer: A clinical and in vitro investigation. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:358–64. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brockdorff N. Noncoding RNA and polycomb recruitment. RNA. 2013;19:429–42. doi: 10.1261/rna.037598.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Chen G, Zeng Y, Zeng J, Lin M, Liu X, et al. Invasion and metastasis-related long noncoding RNA expression profiles in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:7409–22. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui M, Xiao Z, Wang Y, Zheng M, Song T, Cai X, et al. Long noncoding RNA HULC modulates abnormal lipid metabolism in hepatoma cells through an miR-9-mediated RXRA signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2015;75:846–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan H, Tian R, Zhang M, Wu J, Ding M, He J. High expression of long noncoding RNA HULC is a poor predictor of prognosis and regulates cell proliferation in glioma. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:113–20. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S124614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun XH, Yang LB, Geng XL, Wang R, Zhang ZC. Increased expression of lncRNA HULC indicates a poor prognosis and promotes cell metastasis in osteosarcoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2994–3000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu M, Xu Y, Wang J, Zhang E, Sun M, Zheng Y, et al. A novel lncRNA, LUADT1, promotes lung adenocarcinoma proliferation via the epigenetic suppression of p27. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1858. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang MD, Chen WM, Qi FZ, Xia R, Sun M, Xu TP, et al. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and regulates cell proliferation by epigenetic silencing of KLF2. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:57. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0153-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panzitt K, Tschernatsch MM, Guelly C, Moustafa T, Stradner M, Strohmaier HM, et al. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:330–42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng W, Gao W, Feng J. Long noncoding RNA HULC is a novel biomarker of poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31:346. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Z, Lu Y, Xu Q, Tang B, Park CK, Chen X. HULC and H19 played different roles in overall and disease-free survival from hepatocellular carcinoma after curative hepatectomy: A preliminary analysis from gene expression omnibus. DisMarkers. 2015;2015:191029. doi: 10.1155/2015/191029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SB, Sohn G, Kim J, Chung IY, Lee JW, Kim HJ, et al. A retrospective prognostic evaluation analysis using the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;169:257–66. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4682-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao X, Huang X, Zhou Z, Lin X. An improvement of the 2^(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinforma Biomath. 2013;3:71–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nana-Sinkam SP, Croce CM. Non-coding RNAs in cancer initiation and progression and as novel biomarkers. Mol Oncol. 2011;5:483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang G, Lu X, Yuan L. LncRNA: A link between RNA and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:1097–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Ma W, Liu Y. Long non-coding RNA HULC promotes bladder cancer cells proliferation but inhibits apoptosis via regulation of ZIC2 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cancer Biomark. 2017;20:425–34. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulsoom B, Shamsi TS, Afsar NA, Memon Z, Ahmed N, Hasnain SN. Bax, Bcl-2, and Bax/Bcl-2 as prognostic markers in acute myeloid leukemia: Are we ready for Bcl-2-directed therapy? Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:403–16. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S154608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharifi S, Barar J, Hejazi MS, Samadi N. Roles of the Bcl-2/Bax ratio, caspase-8 and 9 in resistance of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8617–22. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.20.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salakou S, Kardamakis D, Tsamandas AC, Zolota V, Apostolakis E, Tzelepi V, et al. Increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio up-regulates caspase-3 and increases apoptosis in the thymus of patients with myasthenia gravis. In Vivo. 2007;21:123–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen C, Wang K, Wang Q, Wang X. LncRNA HULC mediates radioresistance via autophagy in prostate cancer cells. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2018;51:e7080. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20187080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan X. Cancer metastases: Challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:402–18. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myong NH. Loss of CDH1 and Acquisition of VIM in epithelial-mesenchymal transition are noble indicators of uterine cervix cancer progression. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:341–8. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murai T, Yamada S, Fuchs BC, Fujii T, Nakayama G, Sugimoto H, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition predicts prognosis in clinical gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:684–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.23564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li SP, Xu HX, Yu Y, He JD, Wang Z, Xu YJ, et al. LncRNA HULC enhances epithelial-mesenchymal transition to promote tumorigenesis and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via the miR-200a-3p/ZEB1 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7:42431–46. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alizadeh AM, Shiri S, Farsinejad S. Metastasis review: From bench to bedside. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8483–523. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2421-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehner C, Hockla A, Miller E, Ran S, Radisky DC, Radisky ES. Tumor cell-produced matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) drives malignant progression and metastasis of basal-like triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2736–49. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Backer J, Wong AS, Schwanke EL, Stewart BG, Pasdar M. Bcl-2 expression decreases cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3687–700. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karch I, Schipper E, Christgen H, Kreipe H, Lehmann U, Christgen M. Is upregulation of BCL2 a determinant of tumor development driven by inactivation of CDH1/E-cadherin? PLoS One. 2013;8:e73062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]