Abstract

Objective

To describe the design and implementation of a virtual network event at the American Neurological Association (ANA) annual meeting led by the Junior and Early Career Member (JECM) Committee.

Methods

We designed a one‐hour virtual networking session featuring three 15‐minute small group meetings preceded and followed by general remarks. Each small group session consisted of one senior mentor, a junior/early career faculty moderator, and three to four junior/early career mentees. All participants completed an exit survey to evaluate perceived benefit of this event.

Results

We recruited 103 mentees, 26 moderators, and 26 mentors for the event. Mentees were primarily at the resident training level or above (17% students). 56% of registered mentees, 100% of moderators and 96% of mentors attended the event for a total of 110 participants. Due to mentee attrition, each room contained 2‐3 mentees. 90% of respondents felt the session met their goals very well or extremely well. Further, 99% felt this session was at least comparable to in‐person networking at conferences and 60% felt this session was better than in‐person networking.

Interpretation

Virtual networking sessions between junior and senior academic neurologists are feasible and are at least comparable to, if not better than, in‐person conference networking. Future events should consider nuanced mechanisms of matching mentors and mentees, inclusion of ad hoc small groups to foster organic networking, and measures to safeguard against mentee attrition. Future studies should evaluate the long‐term benefits of this event to determine if virtual networking should be utilized moving forward.

Introduction

SARS‐CoV2 has forced many scientific conferences to move to an online format. Although virtual conferences offer several benefits (e.g. reduced travel, increased accessibility), they cannot replicate the organic face‐to‐face meetings which foster networking and mentorship. This presents a particular burden for trainees who rely on in‐person meetings to find new training and job opportunities, to build and foster collaborative relationships, and to improve professional visibility at a national level.

Herein, we present the experience of the Junior and Early Career Member (JECM) Committee of the American Neurological Association (ANA) on designing and implementing a virtual networking event to connect trainees and early career faculty with senior academic mentors in their fields of interest. We describe the methods used to implement this event, attendees’ perceived efficacy of the event and suggested improvements for virtual networking events.

Methods

This project was granted human subjects research exemption by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board.

The event was a 1‐hour session featuring three 15‐min small group meetings preceded and followed by general remarks. We designed each small group session to have one senior mentor, a junior/early career faculty moderator, and three to four junior/early career mentees. Junior/early career was defined as undergraduates, medical and PhD students, residents, fellows, and assistant professors.

We recruited mentees via targeted emails and postings to online communities such as junior/early career members of the ANA, junior/early career registrants of the annual meeting, MD/PhD program coordinators, the Consortium of Neurology Program Directors, followers of personal and ANA Twitter accounts, and the Women Neurologists Group on Facebook. Mentees registered in advance via email link and indicated their subspecialty interests and ANA membership status.

We recruited moderators based on recommendations from ANA JECM Committee members.

We recruited mentors from JECM Committee member recommendations and from solicitations via Twitter and BlackinNeuro (@BlackinNeuro, blackinneuro.com). Given the academic focus of the ANA, all mentors were affiliated with an academic institution and were at the Associate Professor level or higher. Furthermore, we selected mentors to reflect a diversity of institutions, specialties, races, and genders.

We grouped mentees based on shared subspecialty interests and training level as determined by their ANA membership status (student vs. non‐student). We paired mentee groups with three mentors (one mentor for each 15‐min‐long small group session) with comparable subspecialty interests. The networking session was conducted via Zoom and the Zoom Breakout Room feature (Zoom Video Communications, Inc., San Jose, CA). Upon registration, we provided mentors and moderators a virtual background to allow easy identification of roles and interests. Mentees and moderators remained in the same virtual room throughout the networking session, while event staff virtually moved mentors every 15 min. Moderators facilitated productive conversation and kept track of time. Event organizers broadcast global text‐based (i.e., silent) 5‐min and 1‐min warning notifications to all participants.

Following all three sessions, participants returned to the main virtual meeting space and took a seven‐question exit survey.

Results

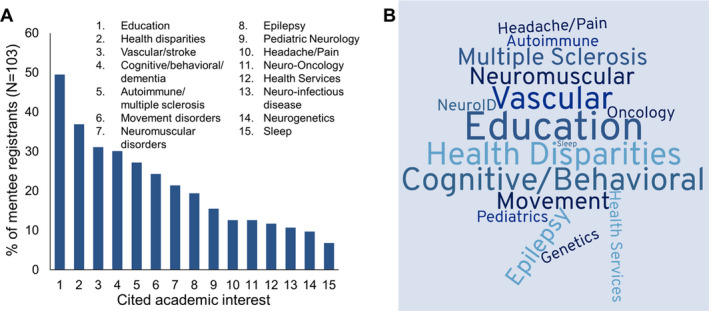

In total, we recruited 103 mentees, 26 moderators, and 26 mentors for the event. Mentees were primarily at the resident training level or above (17% students). Mentee academic interests varied widely; education (49.5%) and health disparities (36.9%) were most common followed by vascular neurology (31.1%) and cognitive/behavioral neurology (30.1%) (Fig. 1). Mentors represented a diverse and illustrious swathe of academic neurology.

Figure 1.

Interests of registered mentees. (A) Interests in descending order of frequency cited; (B) Interests represented as a word cloud based on frequency cited.

56% of registered mentees, 100% of moderators and 96% of mentors attended the event for a total of 110 participants. Due to mentee attrition, each room contained 2‐3 mentees.

Small group discussions focused on broadly applicable and subspecialty‐specific advice for early career advancement. Additional topics from one small group included a discussion by a mentor of having children early in their career as well as a discussion by a mentor who holds leadership positions in diversity and inclusion on the value of ensuring diversity in an academic department.

Exit survey results showed this format of networking was well‐received by attendees. Mentees, moderators, and mentors had complementary goals for the networking session and 90% of respondents felt the session met their goals very well or extremely well (Table 1). Furthermore, of the attendees who had previously attended a conference, 99% felt this session was at least comparable to in‐person networking at conferences and 60% felt this session was better than in‐person networking. We did not formally assess the reasons that virtual networking may be preferable, however, one moderator suggested: “The format allows for an artificial ‘separation’ that I believe allows some people who might otherwise be a bit more reserved to feel comfortable stepping out of that shell…I'd advocate for this sort of virtual format in the future even [when] we return to an in‐person world.”

Table 1.

Perceived efficacy of this networking event by all participants based on exit survey responses.

| Survey Question | Responses | % (N = 103) |

|---|---|---|

| Current level of training | Associate professor or higher | 21 |

| Assistant professor or Instructor | 28 | |

| Resident or Fellow | 34 | |

| Student | 17 | |

| Mentee/Moderator Goals | Meet mentors | 69 |

| Meet peers | 34 | |

| Early career advice | 63 | |

| Job/Fellowship opportunities | 18 | |

| Residency admissions | 12 | |

| Other | 3 | |

| Mentor Goals | Meet mentees | 11 |

| Share career advice | 19 | |

| Give encouragement | 19 | |

| Finding job/fellowship candidates | 4 | |

| Find residency candidates | 2 | |

| Other | 1 | |

| How well did the event meet your goals? | Extremely well | 56 |

| Very well | 34 | |

| Somewhat well | 8 | |

| Not so well | 2 | |

| Did not meet my goals | 0 | |

| How did this virtual event compare to previous in‐person networking at conferences between potential mentors and mentees? | Much better | 26 |

| Somewhat better | 25 | |

| Comparable | 34 | |

| Worse | 0 | |

| Much worse | 1 | |

| Not applicable (first conference) | 17 | |

| Would you participate in this event again? | Yes | 99 |

| No | 1 | |

| Would you recommend participation to a peer? | Yes | 99 |

| No | 1 |

The most common answer to each question is bolded.

Discussion and Future Directions

Virtual networking sessions between junior and senior academic neurologists are feasible and are at least comparable to, if not better than, in‐person conference networking. This session was successful for multiple reasons. First, the high time‐ and financial costs of travel to an in‐person meeting were no longer a barrier and facilitated the recruitment of a diverse group of mentor and mentees. This engendered a more rich conversation regarding the myriad personal factors that affect early career advancement. Second, the virtual format made it easier to approach a senior mentor with questions, with at least one participant noting that this feature may have made networking in the virtual platform easier than networking in person. Third, by moving participants between “virtual breakout rooms” it allowed for multiple mentee–mentor interactions within a short window of time. Other strengths included having a pre‐assigned moderator in the breakout room to facilitate discussion, provide tech support as well as utilizing a virtual background to identify roles and interests.

Weaknesses of this networking event that require future optimization are as follows: (1) Time required to create rational mentor–mentee pairings; (2) Rigid structure of the networking sessions prevented third‐party introductions during the event; and (3) Mentee attrition between registration and the event date that led to smaller group sizes than additionally anticipated (2–3 mentees per room instead of the 3–4 mentees per room).

Future events can address these weaknesses in multiple ways:

Mentor–mentee pairings were initially made based on participant’s reported subspecialty interests and required significant time by the organizers to create pre‐assigned groups. If the networking event were to expand significantly in size, recently developed machine learning approaches using short research abstracts or an individual’s biosketch (which would need to be submitted in advance) could be used to optimally pair mentors and mentees. 1 Anecdotally, the most successful mentee groups were paired not just by interest but also by training level (i.e., medical student mentees in the same room, early faculty in the same room, etc.) and therefore should be taken into account for future sessions. Alternatively, instead of preassigning groups, another option is to let the mentees choose who they want to meet by providing mentees ahead of the session with preconstructed mentor groups and asking them to pick their mentor group on a first come first serve or rank list basis.

To promote more spontaneous conversations, a designated portion of the event could promote ad hoc small groups to continue discussions after the structured mentor–mentee small groups, or allow for introductions between people not otherwise paired in the initial sessions. This allows the event to capitalize on multiple circumscribed, mentor–mentee interactions while also allowing for more protracted conversation as desired.

While almost all invited mentors attended the networking session, only 56% of the mentees who preregistered actually showed up for the networking session. As this was the first such virtual networking event hosted by the ANA, it may have been unclear to mentee registrants that they were being specifically matched with mentors (as opposed to joining a large virtual meeting room where their absence could go unnoticed). One way to remedy this would be to require repeat confirmation of attendance closer to the date following registration and to also let mentees know in advance of the mentors who will be expecting to meet them at the event. Providing materials regarding networking tips and the backgrounds of assigned mentors would also likely decrease mentee attrition. Although rooms were populated with fewer mentees than originally anticipated, attendees still felt the event was successful. Therefore, future events may consider maintaining the ratio of 1 mentor: 1 moderator: 3 mentees per room.

Finally, though most attendees felt this networking event was successful, the true test of success of such events is an ongoing interaction between mentors and mentees after the event is over. Future long‐term studies can determine whether mentors and mentees stayed in touch after this event.

In sum, we successfully hosted a well‐received virtual speed networking event. As more and more traditional in‐person conferences are being converted to a virtual format, virtual networking will play a vital role going forward.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

B.A., E.L., and E.S. were responsible for the concept of the event and draft of the commentary.

Acknowledgements

We owe a debt of gratitude to the mentors who graciously volunteered their time and expertise to this event. Mentors include: Drs. Charlotte Sumner, Nina Schor, Allison Brashear, Tom Carmichael, Amit Bar‐Or, Erika Augustine, Louise McCullough, Robert Buccelli, David Lardizabal, Rachel Salas, Roy H. Hamilton, Charlene Gamaldo, Sharon Lewis, Larry Charleston IV, Reena Thomas, Eric Cheng, Anne Cross, Annapurna Poduri, Jin‐Moo Lee, Stacey Clardy, Frances Jensen, Dave Holtzman, Justin McArthur, Henry Paulson, and Clifton Gooch. We thank Janki Amin, Helen Mack, Nadine Goldberg, and the ANA staff for their help in organizing this event. Dr. Aravamuthan receives grant support through NINDS (5K12NS098482‐02). Dr. Landsness is funded through the AASM Foundation (201‐BS‐19), American Heart Association (20CDA35310607), and NINDS (K08 NS109292‐01A1, 1U01NS099043‐01A1). Dr. Silbermann is funded through the Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development CDA‐2 (1IK2RX003407‐01A1).

Funding Information

Dr. Aravamuthan receives grant support through NINDS (5K12NS098482‐02). Dr. Landsness is funded through the AASM Foundation (201‐BS‐19), American Heart Association (20CDA35310607), and NINDS (K08 NS109292‐01A1, 1U01NS099043‐01A1). Dr. Silbermann is funded through the Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development CDA‐2 (1IK2RX003407‐01A1).

Funding Statement

This work was funded by American Heart Association grant 20CDA35310607; Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development grant 1IK2RX003407‐01A1; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants 1U01NS099043‐01A1, 5K12NS098482‐02, and K08 NS109292‐01A1; AASM Foundation grant 201‐BS‐19.

References

- 1. Achakulvisut T, Ruangrong T, Bilgin I, et al. Improving on legacy conferences by moving online. Elife 2020;20:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]